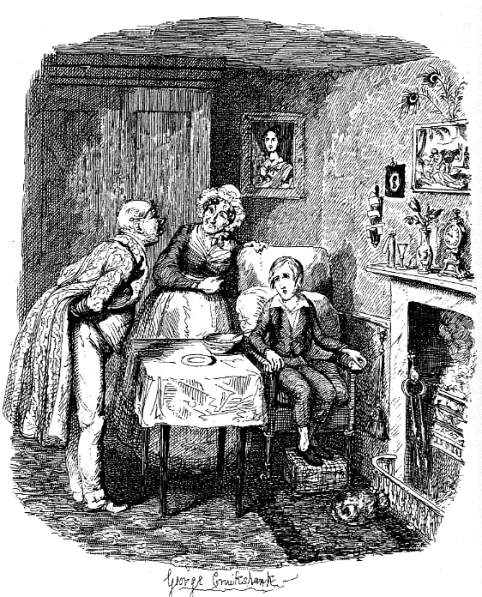

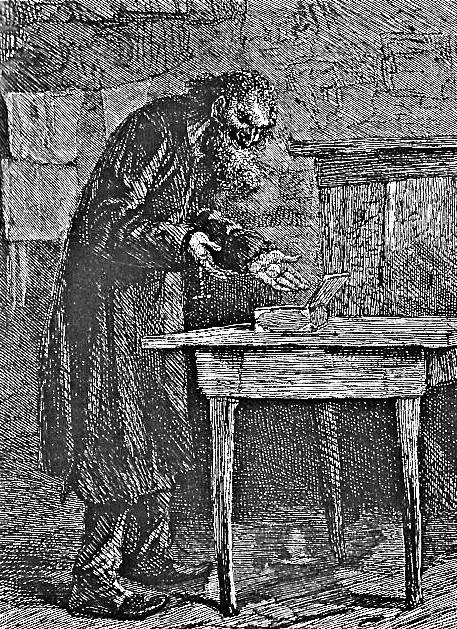

I. Oliver and His Mother’s Portrait

Left: Oliver recovering from fever (1837) by George Cruikshank. Right: Oliver and His Mother's Portrait (1910) by Harry Furniss. [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

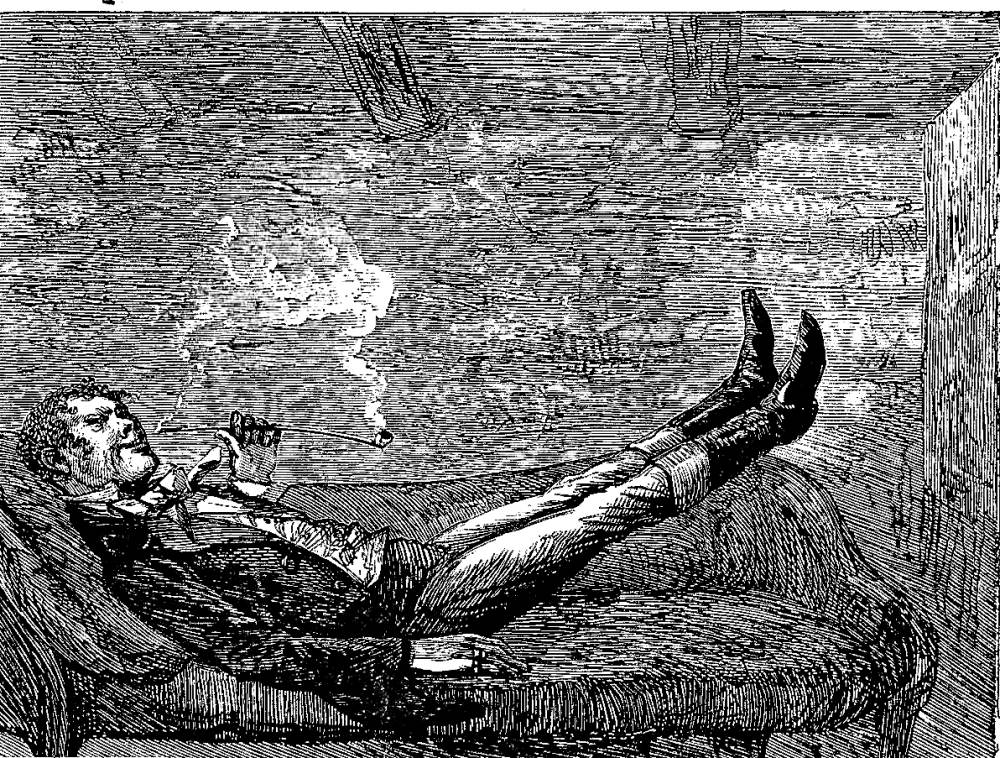

Whereas Charles Dickens begins the novel with the death of Oliver's mother in the workhouse a considerable distance north of London, Harry Furniss's first lithograph from a pen-and-ink wash drawing focuses on the boy's comfortably dozing in an easy chair in the housekeeper's room of Mr. Brownlow's house in Pentonville, north London. Recovering from an acute fever, Oliver finds himself in a comfortable easy-chair and presented with a bowl of hot broth; above him is the oil-portrait of a fashionably dressed young woman of about twenty years of age. In the frontispiece, Furniss combines the passage describes Oliver's fitful slumber over a number of days upstairs with his questioning Mrs. Bedlow about the portrait in her room downstairs. In the frontispiece, the young lady (in fact, Oliver's mother) seems to be looking out of the frame and directly at the reader. The placement and subject matter of this frontispiece reflect Furniss's detailed knowledge of the plot of the entire novel, a knowledge that the original serial illustrator, George Cruikshank, probably lacked when he bagan the commission for Bentley's Miscellany in January 1837.

Like the Household Edition illustrator James Mahoney in 1871, Furniss in 1910 had the definite advantage of having read the entire novel in advance, as well as of having seen Mahoney's twenty-eight wood-engravingsfor the novel and the twenty-four steel-engravings from 1837-38 by Dickens's original illustrator. For his program of "34 original illustrations" announced on the title-page, Furniss rarely elected merely to emulate past practice for the first half of volume III of the Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910). Although the influence of Cruikshank predominates, Furniss is often "original" in his treatment of Cruikshank's subjects, as in his re-thinking and reconfiguration of Oliver recovering from fever (see below), Cruikshank's serial illustration for August 1837, a drawing made expressly at Dickens's behest to make plain Oliver's much-improved circumstances ordained by a beneficent Providence. The Furniss caption makes the identity of the young woman perfectly clear, but (unlike the majority of Furnnis's illustrations) does not point through a quotation or extended caption to a specific moment in the text. On the other hand, in Cruikshank's illustration the portrait's initial relationship to the boy is not clear at all, but the juxtaposition of the plate and the text, and the illustration's placement within the book, point to a highly specific passage. Dickens first draws the reader's attention to the likeness between the portrait in Mr. Brownlow's Pentonville home and the recently arrived "Tom White" in Chapter 12, preparing the reader for the whole series of coincidences involving Mr. Brownlow and Rose Maylie in the novel's "inheritance" plot.

Weeks after his release from detention and the sentence of three months' hard labour after the bookstall owner's testimony has exonerated him, Oliver, weak but recovered from the fever, awakens at Mr. Brownlow's home in Pentonville, north London. Carried downstairs to the room of the grandmotherly housekeeper, Mrs. Bedwin, Oliver pays special attention to a portrait of a young lady in her room. Cruikshank's treatment of the subject of the poor boy taken in and nursed back to health by the elderly bachelor and his kindly housekeeper, Mrs. Bedwin, is both theatrical and narrative; that is, the Regency illustrator has included all the elements that Dickens describes, including the feverish boy in his chair, Mr. Brownlow in his embroidered dressing-gown, such theatrical properties as the table, fireplace, and wardrobe (producing a rather crowded effect), and, above Oliver, the small portrait, a taken-from-the-life study which is complemented by the ornately framed oil painting above the mantelpiece of a suitable biblical analogue, the kindness of the Good Samaritan in Christ's New Testament parable in "The Gospel According to St. Luke" (10: 25-37).

Conspicuous on the wall immediately above and behind Oliver is yet another inset picture, a portrait that proves to be that of Oliver's mother, about whom in his delirium he has dreamed, as if she were his guardian angel. This scene of Oliver's charitable and even loving adults contrasts previous scenes, including that of the "false" Samaritan, the master-thief Fagin; again, as in Oliver introduced to the respectable Old Gentleman, Cruikshank has positioned Oliver to the right and his saviours to the left, Mrs. Bedwin occupying the central position taken by the Artful Dodger in the earlier illustration. Despite the effectiveness of these juxtapositions, the reader has to sort through the crowded details to study the likeness of the tiny portrait and the sickly Oliver.

The Good Samaritan, by the way, was something of a favourite subject with Victorian painters such as George Frederic Watts (1852) and John Everett Millais (1863). Indeed, the parable seems to have been a commonplace for philanthropic activity among the upper-middle and upper classes, as in the low relief sculpture for Sarah Elizabeth Wardroper by George Tinworth (1893-94).

Representations of the Good Samaritan by Watts, Millais, and Tinworth. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

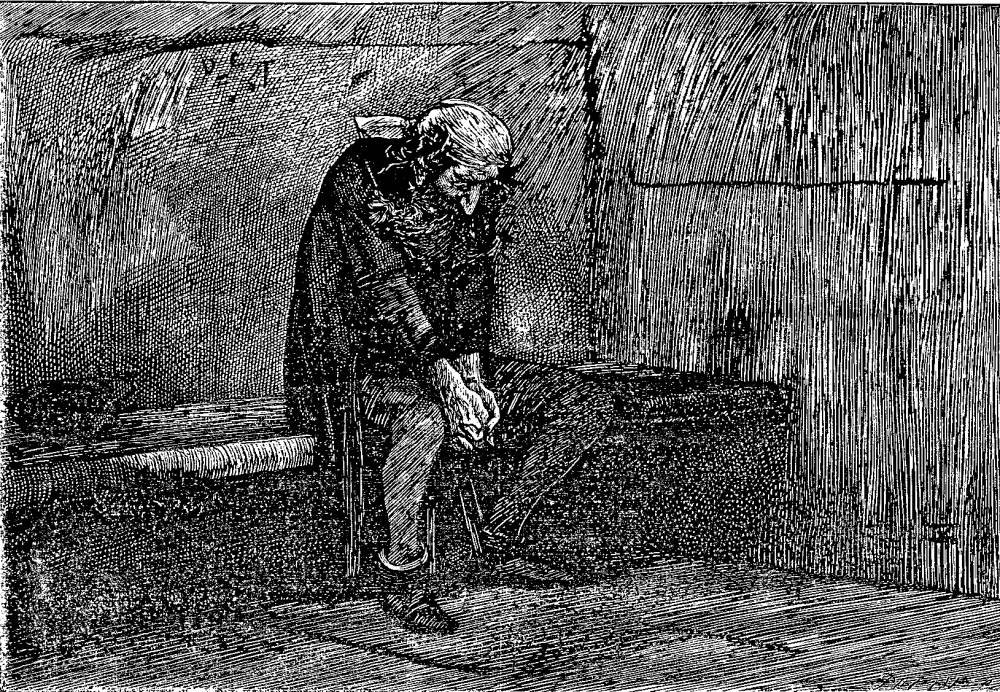

Although in composing the series for the 1871 Household Edition Mahoney had the advantage of being able to study Cruikshank's plates assiduously well in advance of his receiving the Chapman and Hall commission for the first volume in the new edition, he rarely pays homage to Cruikshank's original conceptions, which are often caricatural rather than examples of social realism. Instead, for example, of depicting the tenderness of Mr. Brownlow and Mrs. Bedwin in caring for Oliver, Mahoney elects to show a parallel scene of the boy's ill-treatment by Monks and Fain once they have recaptured Oliver, The boy was lying, fast asleep, on a rude bed upon the floor (see below), in Chapter 19, "In Which a Notable Plan is Discussed and Determined On."

Rejecting the obvious sentimentality and detailism of the Cruikshank original, Furniss dispenses with the other embedded painting, the furnishings, and the attendants in order to focus on the irony of Oliver's dozing beneath the portrait that turns out to be that of the mother whom he never knew but whom he has sensed as an abiding presence. As opposed to the 1846 frontispiece by Cruikshank, which merely alludes to the first of Oliver's "adventures," when he asks the master of the workhouse for more gruel, the Furniss frontispiece refers to the overarching "lost heir" plot in which Providence directs the boy unwittingly to connect with his mother's sister and his father's best friend. Mahoney's 1871 frontispiece (see below) likewise directs the reader to the "lost heir" plot through depicting Monks's attempting to destroy the evidence of Oliver's true identity.

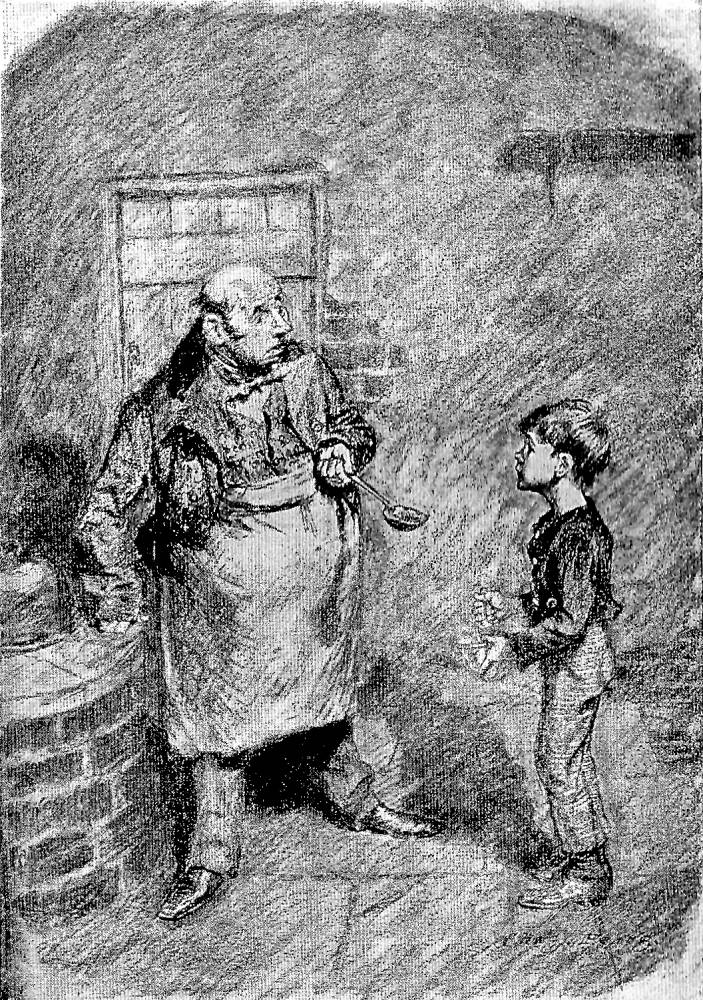

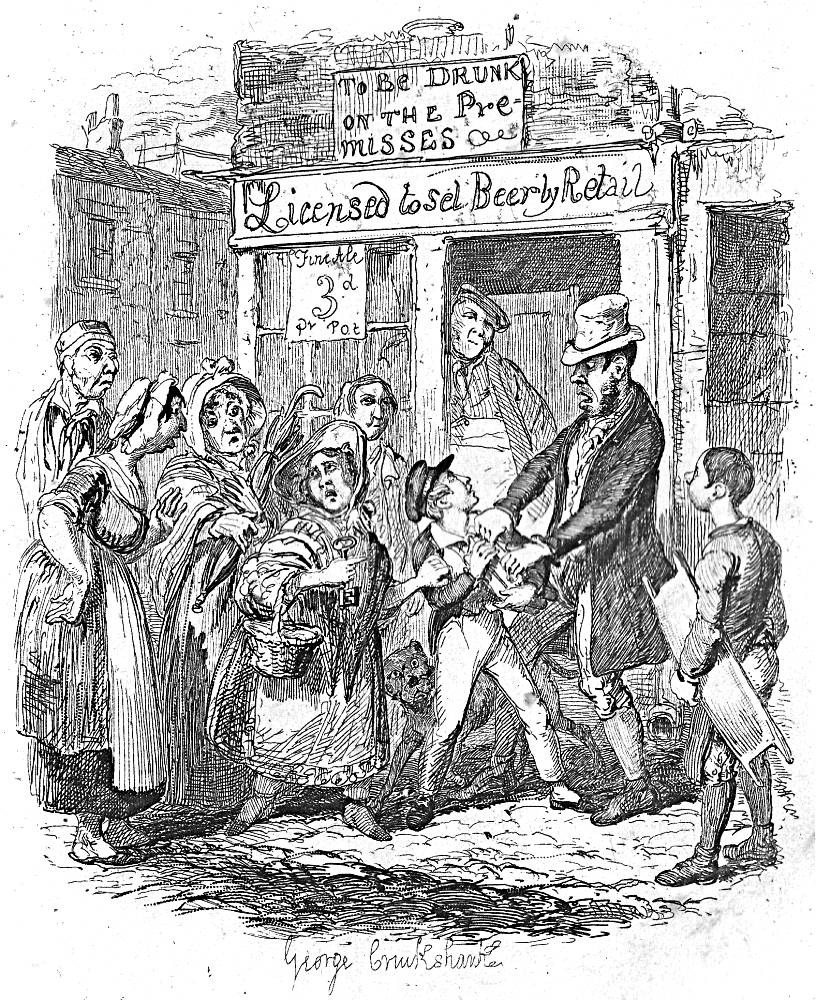

II. "Please, Sir, I want some more."

Left: Oliver Asking for More (1837) by George Cruikshank. Right: Starvation in the Workhouse (1910) by Harry Furniss. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Passage Illustrated: Oliver Asks for More

The evening arrived; the boys took their places. The master, in his cook's uniform, stationed himself at the copper; his pauper assistants ranged themselves behind him; the gruel was served out; and a long grace was said over the short commons. The gruel disappeared; the boys whispered each other, and winked at Oliver; while his next neighbours nudged him. Child as he was, he was desperate with hunger, and reckless with misery. He rose from the table; and advancing to the master, basin and spoon in hand, said: somewhat alarmed at his own temerity:

"Please, Sir, I want some more."

The master was a fat, healthy man; but he turned very pale. He gazed in stupified astonishment on the small rebel for some seconds, and then clung for support to the copper. The assistants were paralysed with wonder; the boys with fear.

"What!" said the master at length, in a faint voice.

The master aimed a blow at Oliver's head with the ladle. . . . [Chapter 2, "Treats of Oliver Twist's Growth, Education, and Board," 13]

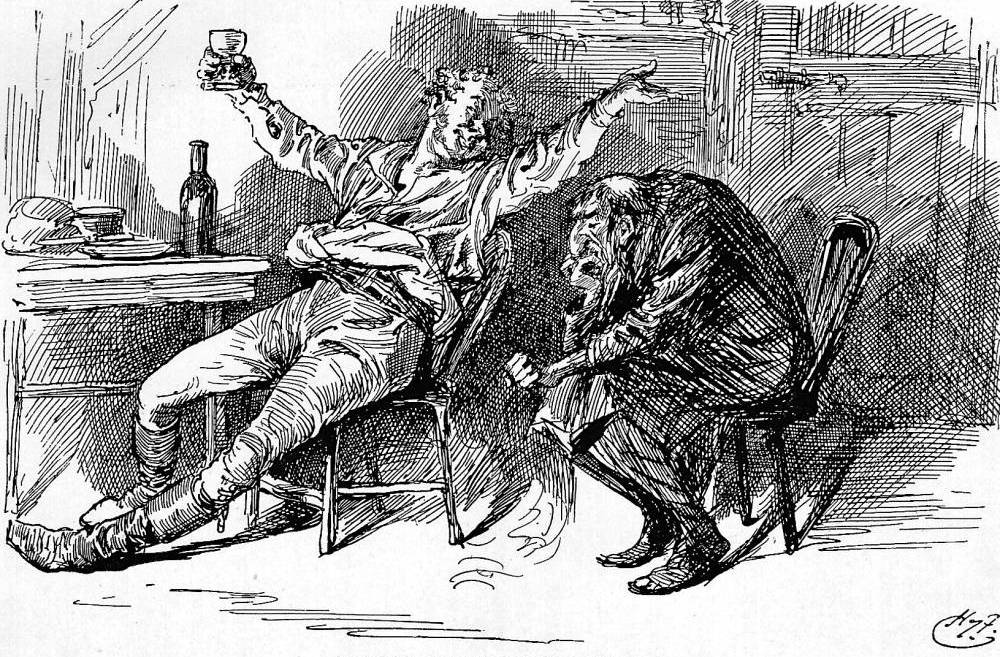

Whereas Dickens's description of "Oliver's Asking for More" (Chapter 2) suggests that the protagonist succumbs to group pressure when he approaches the well-fed master of the workhouse on behalf of the entire body of starving juvenile inmates, Furniss's interpretation depicts Oliver as a plucky rebel confronting insensitive, bloated authority.

Almost two centuries after this scene in the workhouse appeared before the British reading public in the initial (February 1837) number of The Adventures of Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress, it remains familiar to even non-English speakers as a result of dramatisations on stage and film, and even through such cartoons as Oliver Asks for a Doggy Bag in The New Yorker Magazine (2 December 1992). Perhaps few modern readers would identify the plate's stinging social criticism of the workhouse system with an obscure Victorian periodical entitled Bentley's Miscellany, in which the novel first appeared in twenty-four monthly instalments, each with a single-page steel engraving by the celebrated caricaturist George Cruikshank.

To grab a sizeable readership for his new serial, Dickens began the first instalment with the death of a young woman in the workhouse, then quickly moved ahead a decade to show her ill-fed, abused, neglected child confronting a personification of the callous administrators of the new Poor Law. Having been raised in Mrs. Mann's baby farm, on his ninth birthday, the boy returns to "learn a useful trade" (picking oakum, in fact), if he does not succumb to the workhouse regimen, which tends to starve boys to death. In James Mahoney's redrafting (see below) of the famous scene for the The Household Edition in 1871, a rake-thin Oliver innocently gestures towards the fat master with his bowl.

Above: Mahoney's 1871 engraving of the gaunt Oliver's acting as a spokesperson for his fellow starving inmates, Uncaptioned Headpiece for Chapter One. Although the famous incident actually occurs in the second chapter, the Household Edition uses it as a keynote.

The focal point of the picture is clearly the boy and the master, the largest figures in the picture, and nothing separates the the viewer from the naive boy in penitential uniform. In the original 1837 steel engraving the overfed "master" scowls at the temerity of the scrawny waif, while the eight other survivors of the starving system look on in suspense; in contrast, in the Household Edition four decades later, Mahoney has turned the master's face away from the reader, and has repositioned the matron, who now expresses merely modest astonishment (centre rear) at Oliver's unorthodox behaviour. Both the original steel and the later composite woodblock engraving seem to have influenced Furniss's conception of the scene.

Although the lineaments of the scenario are much the same in Furniss's 1910 reinterpretation, the overall effect is far more kinetic and emotionally charged — and not without some comic distortion and melodramatic exaggeration. In particular, Furniss has given the tiny protagonist a look of stern defiance wholly absent in previous interpretations in this David-versus-Goliath confrontation of scrawny underdog taking on the corpulent establishmentarian figure in what amounts to Socialistic propaganda. Whereas previous illustrators have focussed on the plump, incredulous functionary and the emaciated petitioner, Furniss presents the entire social context of the dramatic moment, placing the eight other boys, individually realised, in the foreground so that the reader approaches the lithograph as if it were a theatrical scene, including two shocked elderly female assistants (upper centre).

Left: Charles Pears' early 20th c. revision, focussing on the two contrasting figures, Oliver Twist and the Master of the Workhouse. Centre and right: Clayton J. Clarke's (Kyd's) early 20th c. studies of the rake-then Oliver presenting his plate to the Master of the Workhouse (off-left in e ach case): Oliver Twist (No. 4 in John Player's Cigarette Cards) and Oliver Twist, a watercolour in The Characters of Charles Dickens (c. 1900).

III. Oliver refuses to be Bound over to the Sweep

Passage Illustrated

It was the critical moment of Oliver's fate. If the inkstand had been where the old gentleman thought it was, he would have dipped his pen into it, and signed the indentures, and Oliver would have been straightway hurried off. But, as it chanced to be immediately under his nose, it followed, as a matter of course, that he looked all over his desk for it, without finding it; and happening in the course of his search to look straight before him, his gaze encountered the pale and terrified face of Oliver Twist: who, despite all the admonitory looks and pinches of Bumble, was regarding the repulsive countenance of his future master, with a mingled expression of horror and fear, too palpable to be mistaken, even by a half-blind magistrate.

"The old gentleman stopped, laid down his pen, and looked from Oliver to Mr. Limbkins; who attempted to take snuff with a cheerful and unconcerned aspect.

"My boy!" said the old gentleman, "you look pale and alarmed. What is the matter?"

"Stand a little away from him, Beadle," said the other magistrate: laying aside the paper, and leaning forward with an expression of interest. "Now, boy, tell us what's the matter: don't be afraid."

Oliver fell on his knees, and clasping his hands together, prayed that they would order him back to the dark room — that they would starve him — beat him — kill him if they pleased — rather than send him away with that dreadful man.

"Well!" said Mr. Bumble, raising his hands and eyes with most impressive solemnity. "Well! of all the artful and designing orphans that ever I see, Oliver, you are one of the most bare-facedest." [Chapter 3, "Relates How Oliver Twist was Very Near Getting a Place, Which Would Not Have Been a Sinecure," 20-21]

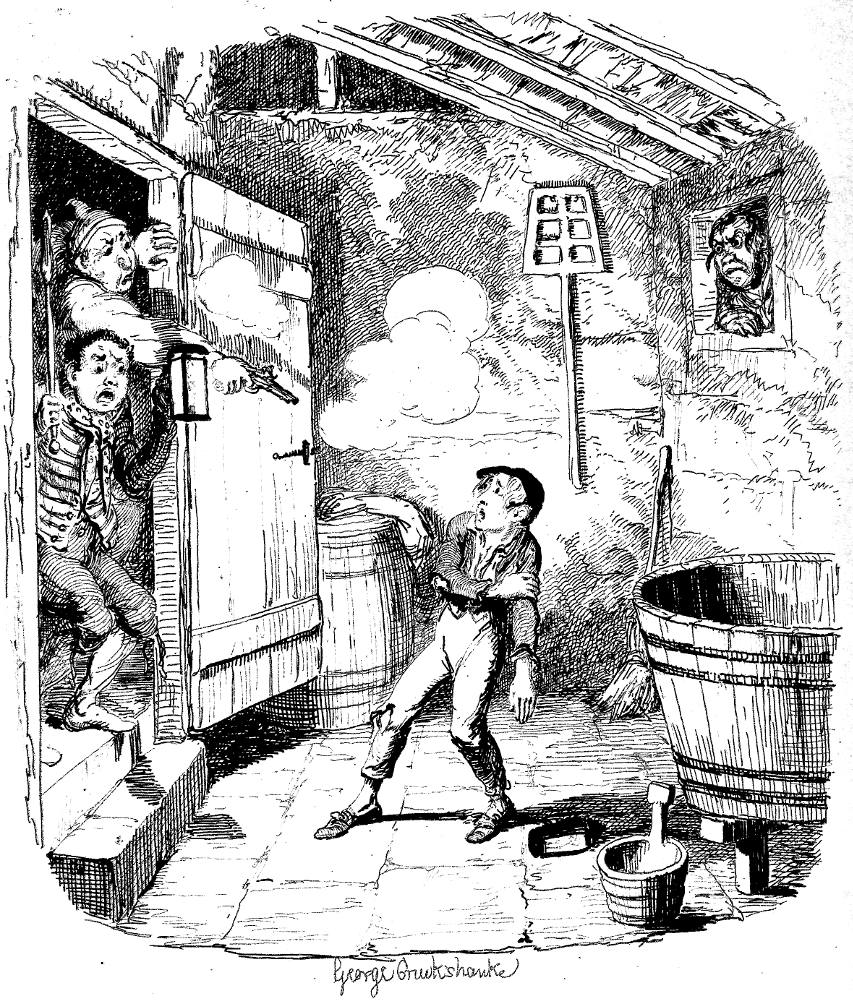

Dickens's description of Oliver's entreating the guardians to reject Gummidge's application to have the boy bound over as his apprentice (Chapter 2, "Treats of Oliver Twist's Growth, Education, and Board") is effectively rendered in a melodramatic scene of heightened gestures and charged poses in George Cruikshank’s Oliver Escapes Being Bound to a Sweep.

Again, Oliver astonishes an authority figure — this time, the parish Beadle, Mr. Bumble — by daring to assert himself. In both the Cruikshank original (see below) and the Furniss revision, Oliver is dwarfed by the adults who will determine his future: looking piously heavenward in Cruikshank but merely indignant in Furniss, Mr. Bumble in uniform; the master of the workhouse, Mr. Limbkins (centre, in front of the magistrate's desk), taking snuff and disregarding the boy entirely; the sooty chimney-sweep Mr. Gamfield, whose villainous, Neanderthal-like countenance is in complete contradiction to the magistrate's describing him as "an honest, open-hearted man" (20); and the benevolent, elderly magistrate with poor vision. Furniss has reorganised the scene so that the trustees (rear) play a diminished role in the hearing. For Chapter 3, "Relates How Oliver Twist was Very Near Getting a Place, Which Would Not Have Been a Sinecure"), Furniss has provided a reinterpretation of the same Cruikshank illustration, magnifying the already considerable proportions of the self-important beadle, Mr. Bumble, with a diminutive Oliver squeezed between the beadle's massive stomach and the bow-legged, sour-faced chimney-sweep (exactly as depicted in his Characters in the Story, the engraved title-page).

Harry Furniss has revised the serial composition so that Oliver's persecutors, Gamfield the chimney-sweep and Bumble the parish beadle, are prominent (shown in close-up), and the chief of the board of trustees, the kindly "magistrate" who actually attends to Oliver's wishes, is considerably reduced and placed in the background; moreover, he is hardly in his stern look in this Furniss re-working an anticipation of the humanitarian Mr. Bownlow. The Master of the Workhouse, Mr. Limkins, is now just an unsympathetic head enjoying snuff and disregarding the proceedings entirely. What matters to Furniss is communicating Oliver's genuine terror. The analeptic reading makes the plate less suspenseful as the reader has already encountered the text realised three pages earlier.

IV. Oliver Aroused

Left: Oliver plucks up a spirit(1837) by George Cruikshank. Right: Oliver Aroused (1910) by Furniss.

Passage Illustrated

"What did you say?" inquired Oliver, looking up very quickly.

"A regular right-down bad 'un, Work'us," replied Noah, coolly. "And it's a great deal better, Work'us, that she died when she did, or else she'd have been hard labouring in Bridewell, or transported, or hung; which is more likely than either, isn't it?"

Crimson with fury, Oliver started up; overthrew the chair and table; seized Noah by the throat; shook him, in the violence of his rage, till his teeth chattered in his head; and collecting his whole force into one heavy blow, felled him to the ground.

A minute ago, the boy had looked the quiet child, mild, dejected creature that harsh treatment had made him. But his spirit was roused at last; the cruel insult to his dead mother had set his blood on fire. His breast heaved; his attitude was erect; his eye bright and vivid; his whole person changed, as he stood glaring over the cowardly tormentor who now lay crouching at his feet; and defied him with an energy he had never known before.

"He'll murder me!" blubbered Noah. "Charlotte! missis! Here's the new boy a murdering of me! Help! help! Oliver's gone mad! Char — lotte!" [Chapter 6, "Oliver, Being Goaded by the Taunts of Noah, Rouses into Action, and Rather Astonishes Him," 42-43]

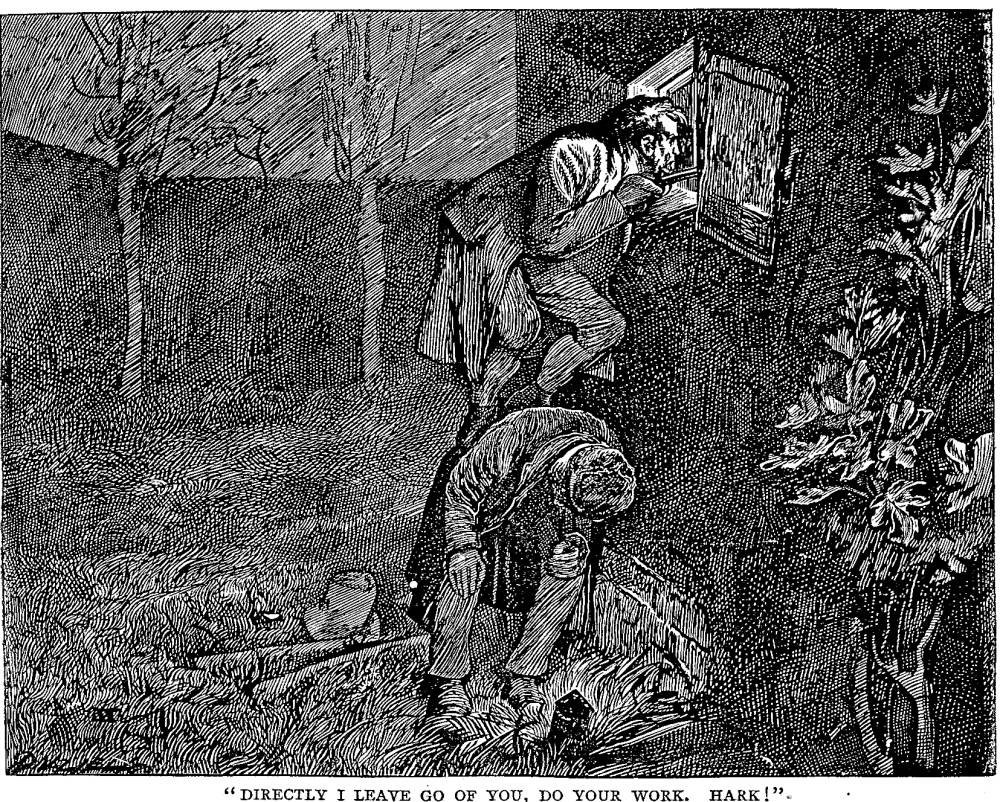

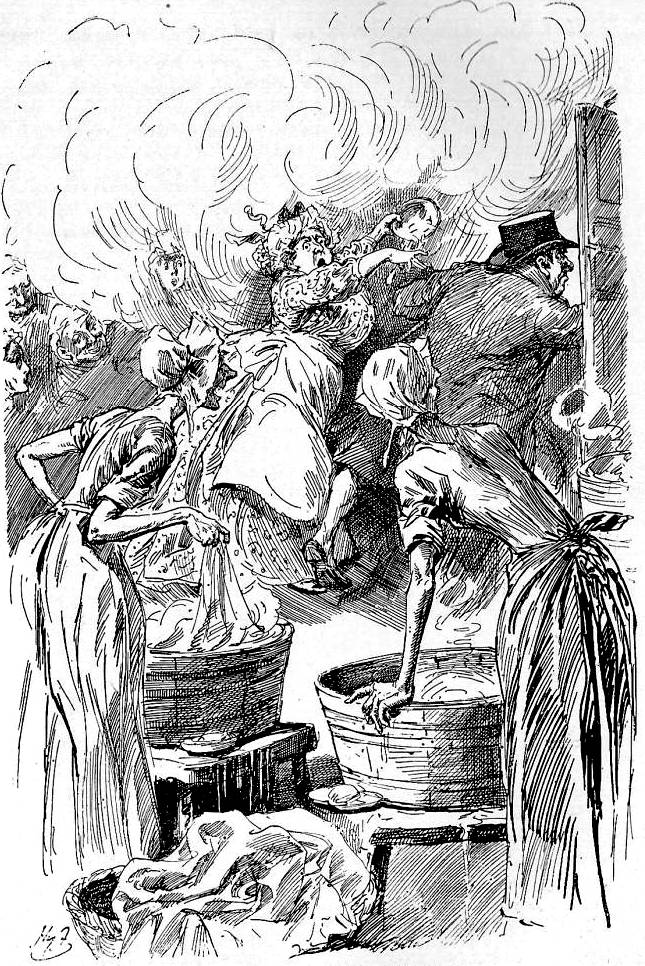

The scene is one which Dickens himself selected for illustration by the resident artist of Bentley's Miscellanyearly in the 1837-39 serial run of the picaresque novel. Although the scene strikes one as melodramatic, with the underdog protagonist thoroughly thrashing the physically superior but cowardly bully, Noah Claypole, undertaker Sowerberry's other apprentice. However, Furniss transforms the scene to comedy with a spindly-shanked waif terrifying the loutish bully. The passage realised actually occurs ten pages later, so that one must read the the illustration proleptically, then flip back to it once one reaches page 43.The reader, even if unaware of the story's trajectory at this point, can anticipate that Oliver's being indentured to the local undertaker will be fraught with complications, despite his being a natural as a mute at funerals, and therefore a genuine asset to Sowerberry.

This subject, like Oliver's asking for more and Oliver's narrowly escaping being apprenticed to a chimney-sweep, was one which Dickens directly proposed to his original illustrator George Cruikshank forBentley's Miscellany as Oliver plucks up a spirit (see above: April 1837). At this point in concluding The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, that other Dickensian protagonist has been unjustly accused and pronounced guilty, and therefore liable for substantial damages, in the March 1837 instalment containing the courtroom scene The Trial (Chapter 34), so that Dickens seems to have been acutely aware of the essential unfairness of life as the bullies and manipulators get the better of his well-meaning central characters.

As the present subject suggests, Dickens realized that Cruikshank excelled at depicting violence and repressed emotion with explosive force, and grotesquerie such as Noah Claypole's grimacing. Cruikshank's organization of the dramatic scene is masterful, with each character in an appropriate pose, the juxtapositions of the four revealing their attitudes to one another, and the whole shaped into a pyramid with the wide-mouthed Mrs. Sowerberry (centre, rear) at the peak, the cowering, gangly-legged Noah at the base, right, and the overturned table drawing the eye to the left-hand corner. As in the accompanying narrative, Oliver in combative stance is centre, and the muscular Charlotte, trying to restrain him, left of centre. Thus, the original serial illustration (April 1837) and its re-issue in 1846 offered Furniss an excellent model, but also posed him a problem in that he could hardly simply copy the original engraving. The Household Edition illustrator, James Mahoney, likewise used the Cruikshank plate as a point of departure for Oliver rather astonishes Noah.

Above: Mahoney's 1871 engraving of the enraged Oliver triumphing over the fallen bully, Oliver rather astonishes Noah.

In Mahoney's engraving, however, Oliver is not being restrained by a towering Charlotte and Mrs. Sowerberry has yet to come through the door, so that the focus in the 1871 Household Edition version is upon a victorious Oliver, standing coolly above the cowering and terrified bully, who lies on the floor amidst shards of shattered china. As is consistent with Mahoney's realistic style, the wood-engraving constitutes a close-up which focusses upon the contrasting reactions of three actors rather than, as in Cruikshank, the chaotic background, or in Furniss, the violent action caught in a freeze-frame, and the sheer terror on Noah's face. Everything in the Mahoney plate seems solid and three-dimensional, as if the reader is a member of an audience watching a theatrical action in which the mayhem has concluded and Oliver's indignation has subsided, so that the overall effect is realistic rather than, as in the other illustrators' treatments, hyperbolic and comical. The treatment of the subject in the Charles Dickens Library Edition is radically different.

Since Furniss enjoyed character comedy immensely, he delights in graphing the chaos that the diminutive Oliver has caused to the kitchen. His enemy, the surly Noah, cries out in terror as Oliver lunges towards him, his fist not quite reaching the bully because a much larger Charlotte has grabbed him by the collar. In the midst of this scene of wanton destruction, a sour-faced Mrs. Sowerberry is glaring are at adversaries from the central door. Everywhere the illustrator's exuberant use of swirling lines creates a sense of the tremendous energy that Noah's taunts have unleashed.

V. Oliver's Flight to London

Left: Harry Furniss’s Oliver on his long weary journey haunted by visions of those whose cruelty forced him to run away. Middle: James Mahoney's title-page vignette of Oliver at the Milestone prepares the reader from the outset for Oliver's escaping the Sowerberrys (1871). Right: Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s Oliver and Little Dick (1867).

Passage Illustrated: Oliver starts for London

Oliver reached the stile at which the by-path terminated; and once more gained the high-road. It was eight o'clock now. Though he was nearly five miles away from the town, he ran, and hid behind the hedges, by turns, till noon: fearing that he might be pursued and overtaken. Then he sat down to rest by the side of the milestone, and began to think, for the first time, where he had better go and try to live.

The stone by which he was seated, bore, in large characters, an intimation that it was just seventy miles from that spot to London. The name awakened a new train of ideas in the boy's mind.

London! — that great place! — nobody — not even Mr. Bumble — could ever find him there! He had often heard the old men in the workhouse, too, say that no lad of spirit need want in London; and that there were ways of living in that vast city, which those who had been bred up in country parts had no idea of. It was the very place for a homeless boy, who must die in the streets unless some one helped him. As these things passed through his thoughts, he jumped upon his feet, and again walked forward. [Chapter 8, "Oliver Walks to London. He Encounters on the Road a Strange Sort of Young Gentleman," 51-52]

Dickens's description of Oliver's stopping by Mrs. Mann's baby-farm to bid little Dick, his only friend, a fond and reluctant farewell (Chapter 7) is the subject of Eytinge's only illustration of the protagonist in the Diamond Edition, Oliver and Little Dick (see below); there is no comparable illustration in the instalments of the novel as originally published in Bentley's Miscellany. However, alluding to Oliver's departure for London in Chapter 8, Mahoney has provided a title-page vignette for the 1871 that depicts Oliver after the tearful scene with little Dick, Oliver at the Milestone (see above), which dramatizes the boy's confusion as to what he should do.

The keynote for Furniss's illustration of a scene heretofore unattempted by illustrators is not the description of the natural environment or the hgh-road to London, but the briefly sketched in psychological dimension of Oliver's running away from everything he has ever known: "fearing that he might be pursued and overtaken" (51) is the basis for the grotesque vegetation and the psychologically projected figures in the sky. Although the above passage is, indeed, that which both Mahoney and Furniss had in mind for their illustrations of Oliver's running away to London, Mahoney does not specify a particular passage in Chapter 8, and Furniss provides a caption that synthesizes the opening two paragraphs: "Oliver on his long weary journey haunted by visions of those whose cruelty forced him to run away" (48). The nightmarish figures fill the sky above a horizon-line of five coffins which echo the shape of the milestone on which the already-weary Oliver, with packsack and staff, rests, as a gnarled, denuded tree, upper left, reinforces the threat that the environment poses the child-traveller, in contrast to the inhumanity of the exploitative society he now leaves behind him.

The Mahoney and Furniss images of Oliver — alone, unfriended, and in doubt as to his course in life as he puts behind him childhood in the workhouse and his apprenticeship to the grim undertaker (whom Furniss characterizes as a top hatted skeleton waving an umbrella, upper left) — is a suitable keynote for the adventures of the orphan in the criminal underworld of the metropolis. In the Cruikshank illustration after Oliver's outburst at the undertaker's, Oliver is already on the northern outskirts of London, at the marketplace of Barnet at sunrise, when he encounters the outlandish figure of Jack Dawkins (otherwise, The Artful Dodger), who introduces the waif to that "kindly, old gentleman," Fagin, in Oliver introduced to the respectable Old Gentleman (May 1837), a characterisation of the juvenile pickpocket which Mahoney used as the basis for "Hello, my covey! What's the row?" (see below). Chipper, self-confident, and self-assured, The Artful at this point is everything that Oliver is not.

Furniss has assimilated the earlier Mahoney composition so that Oliver, like Dante at the beginning of The Divine Comedy, is lost in a dense wood without a guide at the beginning of his journey towards enlightenment. The proleptic reading of the Mahoney and Furniss illustrations alerts the reader to Oliver's being forced out of his place at Sowerrberry's and determining to undertake the journey on foot to London without resources or assistance. The trauma he has endured over the course of his miserable childhood is represented by the aetherial, cartoon-like figures in the sky, while the continual prospect of death, by starvation and neglect, is suggested by the five coffins on the skyline. Furniss's treatment is an interesting and innovative synthesis of the melodramatic pose of the boy and the psychological terrors he must now confront: the fear of the turbulent and menacing woods (left) and the fear of being apprehended and returned the world of the workhouse (as represented by Bumble, swinging his cane; the chairman of the trustees, pointing at Oliver; and the black-faced chimney sweep, waving his broom, upper right) and the undertaker's (Sowerberry, his wife, Charlotte, and, most prominently, a hectoring Noah Claypole above three of the coffins on the horizon).

Having bid his only friend in the world, Little Dick, a tearful farewell at Mrs. Mann's baby-farm, Oliver now strikes out on the high road to London, as so many picaresque heroes before him — including Henry Fielding's Tom Jones and Sir Walter Scott's Jeanie Deanes (figures who, like Roderick Random and Peregrine Pickle, Dickens encountered in his boyhood reading). In his Household Edition volume of David Copperfield (which he illustrated just the year after Mahoney's volume for Oliver Twist came out in the same edition) lead Household Edition illustrator Fred Barnard makes palpable the connection between the earlier picaresque "adventure" of 1837-39 and the classic Bildungsroman of 1849-50 by making his keynote the title-page vignette of the wayfaring David, exhausted and in rags, escaping the misery of his working-class existence in the metropolis for the hope of a better, middle-class life with a distant relative in Dover.

Although David is escaping from London rather than hastening towards it as a refuge, the similarity in the plates suggests that Barnard may have seen the connection between Sowerberry's runaway apprentice, the victim of a stern stepfather, and the boy who worked in Warren's Blacking at Hungerford Stairs. Both title-page vignettes reveal Dickens's deep concern with abandoned and abused children — a reflection of his own troubled and psychologically damaging experiences with child labour. Then, too, as a student of the great visual satirist William Hogarth, like Dickens Barnard could not have missed the connection between the novelist's picaresque heroes and the protagonists of the visual "progresses" of The Rake's Progress (1733) and The Harlot's Progress (1734). Oliver, after all, is about to enter the world of Henry Fielding's Jonathan Wilde and William Hogarth's Gin Lane, inhabited by the criminal mastermind, a gang of pickpockets, a violent housebreaker, and a prostitute with a heart of gold.

VI. Oliver falls in with the Artful Dodger

Left: Harry Furniss’s "Hullo, my covey! What's the row?" said this strange young gentleman to Oliver. "I am very hungry and tired," replied Oliver; the tears standing in his eyes as he spoke. "I have walked a long way. I have been walking these seven days." (1910). Right: James Mahoney's engraving of Oliver's fateful meeting with The Artful Dodger at Barnet, "Hello, my covey! What's the row?" (1871)

Passage Illustrated

The boy who addressed this inquiry to the young wayfarer, was about his own age: but one of the queerest looking boys that Oliver had ever seen. He was a snub-nosed, flat-browed, common-faced boy enough; and as dirty a juvenile as one would wish to see; but he had about him all the airs and manners of a man. He was short of his age: with rather bowlegs, and little, sharp, ugly eyes. His hat was stuck on the top of his head so lightly, that it threatened to fall off every moment — and would have done so, very often, if the wearer had not had a knack of every now and then giving his head a sudden twitch, which brought it back to its old place again. He wore a man's coat, which reached nearly to his heels. He had turned the cuffs back, half-way up his arm, to get his hands out of the sleeves: apparently with the ultimate view of thrusting them into the pockets of his corduroy trousers; for there he kept them. He was, altogether, as roystering and swaggering a young gentleman as ever stood four feet six, or something less, in his bluchers.

"Hullo, my covey! What's the row?" said this strange young gentleman to Oliver.

"I am very hungry and tired," replied Oliver: the tears standing in his eyes as he spoke. "I have walked a long way. I have been walking these seven days."

Cruikshank did not illustrate Dickens's description of Oliver's meeting the curious figure of the London pickpocket at the marketplace in Barnet; Mahoney was the first illustrator to do so.

Having run away from his apprenticeship with Sowerberry, Oliver determines to walk the Great North Road to London after he has visited Mrs. Mann's baby-farm to say goodbye to Little Dick, the only friend he made there. Befriended on the road by a charitable turnpike keeper and an elderly lady, on the seventh morning Oliver limps slowly into the marketplace of Barnet at sunrise. At this point, he encounters a boy only a little older than himself, but wearing the clothing and affecting the self-confident manner of an adult. In fact, today the Borough of Barnet is Greater London's second-largest, but in the period in which Dickens has set the story, it was still a small market-town north of central London, in the county of Hertfordshire.

Mahoney, the previous significant illustrator of the novel, provided Furniss with a likely model in the highly popular 1871 volume in the Household Edition, showing Oliver's initial encounter with the self-confident Artful Dodger (and by extension London's criminal underworld) in "Hullo, my covey!What's the row?" The Mahoney and Furniss images of Oliver, alone, unfriended, and in doubt as to his course in life, contrast the runaway apprentice from the north of England workhouse with the streetsmart figure, who introduces the waif to that "kindly, old gentleman," Fagin. Chipper, self-confident, and self-assured, The Dodger at this point is everything that Oliver is not.

Furniss has assimilated the earlier Mahoney composition, but unlike Mahoney's generalized background, he particularizes the morning scene in the suburban marketplace with public houses on either side of the borough high street, as well as the substantial publican conversing with the uniformed postman (surely an anachronism), rear centre. Far from being a realistic representation of the morning scene, despite the architectural backdrop and the birds, Furniss's interpretation is markedly impressionistic, with jagged lines representing the energy of the Cockney youth.

Depictions of The Artful Dodger, 1837 to 1910

Left: Sol Eytinge, Junior's The Artful Dodger and Charley Bates. Centre: George Cruikshank's original version of Oliver introduced to the respectable Old Gentleman. Right: Clayton J. Clarke's watercolour version of The Artful Dodger for Player's Cigarette Cards (1910).

VII. The Thieves' Kitchen. Oliver is Shown 'How It Is Done'

Left: Cruikshank’s Oliver introduced to the respectable Old Gentleman (May 1837). Right: Furniss’s The Thieves' Kitchen. Oliver is Shown "How It Is Done (1910).

Passage Illustrated

When the breakfast was cleared away; the merry old gentleman and the two boys played at a very curious and uncommon game, which was performed in this way. The merry old gentleman, placing a snuff-box in one pocket of his trousers, a note-case in the other, and a watch in his waistcoat pocket, with a guard-chain round his neck, and sticking a mock diamond pin in his shirt: buttoned his coat tight round him, and putting his spectacle-case and handkerchief in his pockets, trotted up and down the room with a stick, in imitation of the manner in which old gentlemen walk about the streets any hour in the day. Sometimes he stopped at the fire-place, and sometimes at the door, making believe that he was staring with all his might into shop-windows. At such times, he would look constantly round him, for fear of thieves, and would keep slapping all his pockets in turn, to see that he hadn’t lost anything, in such a very funny and natural manner, that Oliver laughed till the tears ran down his face. All this time, the two boys followed him closely about: getting out of his sight, so nimbly, every time he turned round, that it was impossible to follow their motions. At last, the Dodger trod upon his toes, or ran upon his boot accidentally, while Charley Bates stumbled up against him behind; and in that one moment they took from him, with the most extraordinary rapidity, snuff-box, note-case, watch-guard, chain, shirt-pin, pocket-handkerchief, even the spectacle-case. If the old gentleman felt a hand in any one of his pockets, he cried out where it was; and then the game began all over again. [Chapter 9, "Containing Further Particulars Concerning the Pleasant Old Gentleman, and his Hopeful Pupils," 63]

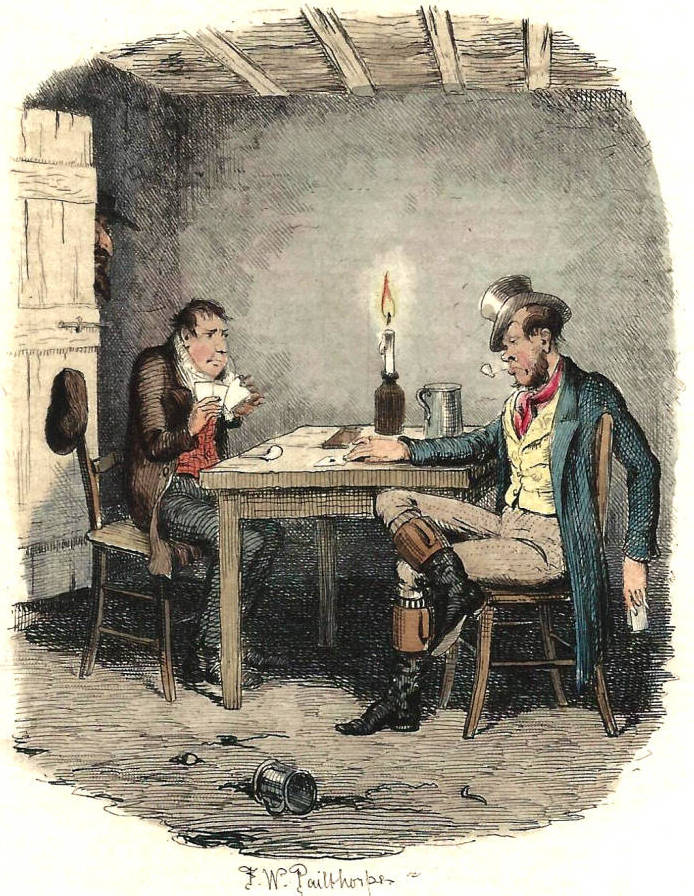

This subject, like Oliver's asking for more and Oliver's narrowly escaping being apprenticed to a chimney-sweep, was probably one that Dickens directly proposed to George Cruikshank. In this early plate, Fagin acts as a surrogate father to five boys, including Charley Bates (right) and Jack Dawkins (centre). However, since he seems oblivious to the fact that two of the boys are smoking long, clayed pipes as he prepares supper with a gridiron, Fagin may be in middle-class terms an inadequate or inappropriate father figure. The multiply-pronged toasting fork he holds may even imply his fiendish machinations and Satanic powers, but literally it points towards his domestic supervisory capacity in the Thieves' Kitchen.

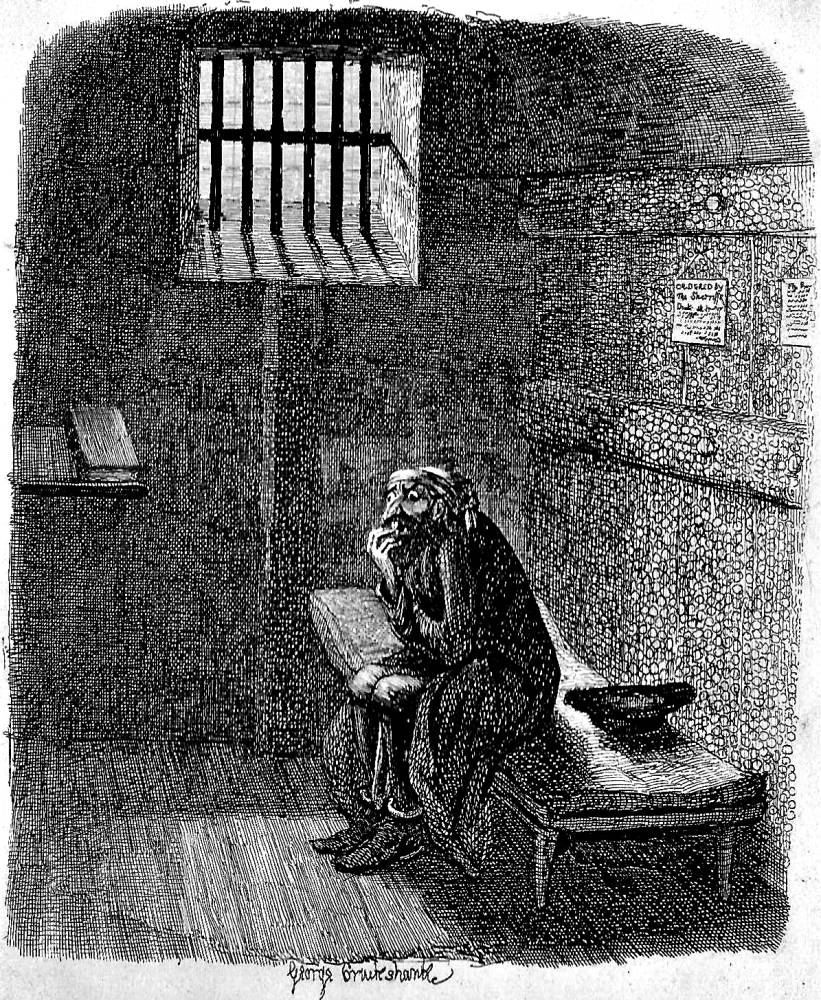

At the end of the century for his Character Sketches from Dickens, the celebrated Dickens illustrator Kyd (J. Clayton Clarke) depicted Fagin not as the boys' instructor or tutor in the criminal arts, but as the boys' provider, toasting fork in hand, in Fagin (see below), an image he reproduced for Player's Cigarette Card No. 2 in a series of fifty: a hideous, red-bearded, red-haired monster in tattered dressing-gown and slippers, with a toothy, atavistic smile. Other illustrators have kinder to the master-thief, and Furniss's initial illustration of Fagin, in top hat and tailcoat, and striding forward, cane in hand, is more flattering by far than Kyd's as it shows a dynamic, active, bustling teacher rather than a hideous troll with fangs ready to devour incautious children. Dark, menacing, unkempt, Fagin in Eytinge's single Diamond Edition illustration is neither parent, nor tutor, nor yet a monster, but the quintessential miser who neglects even personal hygiene and adequate clothing in his pursuit of "personal property."

The character of Fagin is neither a Dickens or Cruikshank original, for such thief-takers, fences, and master criminals were commonplace in London lore and street gazettes. Dickens may have based Fagin partly upon Peachum in John Gay's The Beggar's Opera (1726) and partly upon such actual nefarious characters such as Ikey Solomon (1787-1850), born in the east end of London and notorious as a receiver of stolen goods. However, unlike Fagin, he was a practising Jew who successfully avoided capture on a number of occasions before sacrificing his freedom in the United States to join his wife, who had been sentenced to transportation to Tasmania (in those days, Van Diemen's Land). Like The Artful Dodger, Fagin is now part of our popular culture, and remains one of Dickens's most frequently illustrated and most recognizable characters thanks in part to Lionel Bart's West End production (1960), David Merrick's Broadway (1963) musical Oliver!, and on David Lean's 1948 cinematic adaptation with Ron Moody starring as Fagin).

Dickens, realizing that Cruikshank excelled at depicting the sordid, grotesque criminal underworld of the metropolis, gave him a suitable subject. Cruikshank organizes the dramatic scene masterfully, with each character in an appropriate pose, the juxtapositions of the four revealing their attitudes to one another, and the whole organized by the gestures and eye contact of the three principals: Fagin, juxtaposed with the cooking fire (left), the casual Dodger, indicating by his gesture the new-comer, and Oliver, curious and respectful (right). The moment, however, is static, like a theatrical tableau. In contrast, Furniss, who avoids much background detail, highlights the four figures as he gives us a "freeze-frame" in which he captures all four characters in motion; Oliver, no longer the victim, is being entertained as he seems to have found a home and family at last. That he is deluded in so thinking will become shortly apparent. An extension of this scene, which Felix Octavius Carr Darley provides in his 1888 Character Sketches from Dickens, is Oliver's trying out his own pickpocketing skills on a playful Fagin, a scene which perhaps undermines the naiveté with which Dickens invests Oliver in the Thieves' Kitchen.

Left: Darley's version of the same scene selected by Furniss, Fagan [sic] and Oliver Twist (1888). Centre: Eytinge's Diamond Edition wood-engraving of the master thief examining his secret strongbox in Fagin (1867). Right: Kyd's widely-disseminated study of Fagin on a Player's cigarette card, Fagin (1910).

Above: Mahoney's 1871 engraving of Fagin's chagrin when he learns that Charley and The Dodger have botched their pickpocketing expedition at The Green, and have lost Oliver, in "What's become of the boy?".

VIII. Oliver's Eyes are opened

Left: Cruikshank’s Oliver amazed at the Dodger's mode of going to work (July 1837). Right: Furniss’s The Thieves' Kitchen. Oliver's Eyes are opened (1910).

Passage Illustrated

The old gentleman was a very respectable-looking personage, with a powdered head and gold spectacles. He was dressed in a bottle-green coat with a black velvet collar; wore white trousers; and carried a smart bamboo cane under his arm. He had taken up a book from the stall, and there he stood, reading away, as hard as if he were in his elbow-chair, in his own study. It is very possible that he fancied himself there, indeed; for it was plain, from his abstraction, that he saw not the book-stall, nor the street, nor the boys, nor, in short, anything but the book itself — which he was reading straight through: turning over the leaf when he got to the bottom of a page, beginning at the top line of the next one, and going regularly on, with the greatest interest and eagerness.

What was Oliver's horror and alarm as he stood a few paces off, looking on with his eyelids as wide open as they would possibly go, to see the Dodger plunge his hand into the old gentleman's pocket, and draw from thence a handkerchief! To see him hand the same to Charley Bates; and finally to behold them, both, running away round the corner at full speed.

In an instant the whole mystery of the handkerchiefs, and the watches, and the Jewels, and the Jew, rushed upon the boy's mind. He stood, for a moment, with the blood so tingling through all his veins from terror, that he felt as if he were in a burning fire; then, confused and frightened, he took to his heels; and, not knowing what he did, made off as fast as he could lay his feet to the ground. [Chapter 10, "Oliver becomes better acquainted with the characters of his new associates; and purchases experience at a high price. Being a short, but very important chapter, in this history," 67-68]

Dickens's description of the attempted robbery in Chapter 10 emphasizes Oliver’s strong emotional reactions: He looks surprised when Charley Bates describes the "very respectable-looking personage, with a powdered head and gold spectacles . . . in a bottle-green coat with a black-velvet collar" (67), and then becomes shocked and horrified as the Dodger picks the gentleman's pocket to purloin his silk handkerchief. Furniss, however, captures neither of these stronger emotions. A scene well-known from the original Cruikshank series in the July 1837 issue of Bentley's Miscellany, the theft of Mr. Brownlow's silk handkerchief continues the boy's "progress" through criminal underworld in the tradition of Henry Fielding's Jonathon Wilde and William Hogarth's Gin Lane. For the London readers of the 1830s the scene would have seemed frighteningly real because it draws the viewer's attention to those executing the crime, since the light-fingered street boys often absconded with the fruits of their crime without even being detected. However, the scenario of street urchins robbing an oblivious victim would have been almost hackneyed by 1910. Whereas in Cruikshank's illustration the bookseller (left) observes with growing alarm what is happening to his customer, in the Furniss treatment the bookseller (centre) cannot see Oliver at all, and probably cannot see The Artful Dodger; he is curious but does not cry out in alarm to warn his customer. His testimony, therefore, several pages after the illustration placed in Chapter 11, is somewhat suspect in that, at least according to Furniss's plate, he can have seen only Charley Bates clearly, and would have had Oliver outside his field of vision. In this sense he misrepresents or misrealizes Dickens’s text.

Other illustrators approached this scene differently. Mahoney, the illustrator of the 1871 Household Edition, depicts the pursuit of Oliver by the mob through the marketplace, but he does not actually show the robbery.

Mahoney’s "Stop thief!"

Mahoney depicted Oliver's genuine terror at being mistaken for the actual thief while the real culprits, part of the mob (left) are already looking for an opportunity to break away. In the Furniss sequence, we proceed from the robbery to Mr. Grimwig and Mr. Brownlow waiting for Oliver's return from that same book-seller, whereas in the original sequence we advance directly to the more dramatic moment in which Sikes and Nancy apprehend Oliver. Mahoney, on the other hand, lays the groundwork for the revelation of the plot between Monks and Fagin in "What's become of the boy?" (Ch. 13).

In Furniss's introduction of Mr. Brownlow, who becomes a significant character in the latter part of the novel, the viewer learns very little about him, and may also be surprised that Oliver (left), the waif from the northern workhouse, is so well dressed. Charley and The Artful Dodger appear here in precisely the clothing in which Furniss dresses them in The Dodger's Toilet in Chapter 17. Such visual continuity is important in the Furniss sequence because he effectively foregrounds the figures by moving the background into obscurity, minimally sketching in such details as are consistent with the settings that Dickens has stipulated. This particular plate provides an unusual degree of detail by sketching in the bookstall, which contains prints as well as volumes. By the time that the reader encounters the robbery scene in the text, Oliver is being arraigned before the severe police magistrate Mr. Fang, in Chapter Eleven.

IX. Waiting for Oliver

Left: Eytinge’s Mr. Brownlow and Mr. Grimwig (1867). Right: Furniss’s Waiting for Oliver (1910).

Passage Illustrated

"Let me see: He'll be back in twenty minutes, at the longest," said Mr. Brownlow, pulling out his watch, and placing it on the table. "It will be dark by that time."

"Oh! you really expect him to come back, do you?" inquired Mr. Grimwig.

"Don't you?" asked Mr. Brownlow, smiling.

The spirit of contradiction was strong in Mr. Grimwig's breast, at the moment; and it was rendered stronger by his friend's confident smile.

"No," he said, smiting the table with his fist, "I do not. The boy has a new suit of clothes on his back, a set of valuable books under his arm, and a five-pound note in his pocket. He'll join his old friends the thieves, and laugh at you. If ever that boy returns to this house, sir, I'll eat my head."

With these words he drew his chair closer to the table; and there the two friends sat, in silent expectation, with the watch between them. [Chapter 14, "Comprising further particulars of Oliver's stay at Mr. Brownlow's, with the remarkable prediction which one Mr. Grimwig uttered concerning him, when he went out on an errand," 104]

There is no surviving correspondence regarding the novelist's instructions about the initial appearance of either the kindly Mr. Brownlow or his sardonic opposite, Mr. Grimwig. Furniss elevates the status of Brownlow's cynical friend by depicting him at this critical junction in the story. Indeed, Furniss shows Grimwig's expression, and distinguishes him from Brownlow by his full head of hair, his rather old-fashioned clothing (he wears breeches, whereas Browlow wears trousers), and his greater physical bulk. This Bunyanesquely-named character’s studied misanthropy is only superficial. Put on like a costume, it hides a kind heart as Mr. Grimwig counters his friend's optimistic appraisal of Oliver with world-weary pessimism. Furniss portrays the two wealthy, middle-aged bourgeoisie,seen in earlier editions such as the Diamond Edition (1867) wood-engraving Mr. Brownlow and Mr. Grimwig, as rather different physical types. In the 1837-38 serial publication, Cruikshank does not represent Mr. Grimwig at all, but does depict Mr. Brownlow in a series of illustrations, notably Oliver recovering from fever. In this early illustration, Cruikshank presents Mr. Brownlow as an antitype to Fagin — an authentic rather than an ersatz Good Samaritan, wearing a clean dressing-gown, and facilitating the boy's recovering from a fever.

The Furniss illustration emphasis the different attitudes that the friends bring towards the putative return of the boy that the humanitarian Brownlow has brought into his own home to nurse back to health. Grimwig is certain that the boy will revert to his criminal associates (with the books and the five-pound note), and Brownlow certain that the boy will return shortly from returning the books to the book-seller at The Green. The cynical Grimwig, at heart a decent man who does not want to see his friend disappointed, revises his opinion of Oliver later in the story. Although many illustrators of the novel offer several interpretations of the philanthropic Brownlow, the only other artist to do justice to Grimwig as a student of human nature is Harry Furniss in his rather more animated treatment of this scene in Waiting for Oliver, in which the pair are studying Brownlow's gold pocket-watch open on the table between them (and therefore the focal point of the illustration) and awaiting the end of the predicted twenty minutes. Eytinge's illustration conveys a far subtler sense of the elderly bachelors with contrasting natures — and includes both the pocket-watch and the portrait of Oliver's mother (strategically placed, upper centre). Mahoney's study of the pair fails to distinguish one friend from the other in the scene in chapter seventeen in which the avaricious Bumble turns up at Brownlow's home in Pentonville in response to the advertisement in theLondon newspaper offering five guineas for information that will "tend to throw any light upon [Oliver's] previous history" (Illustrated Library Edition, 126).

Furniss permits us to study Grimwig's bluff, slightly smiling visage ("I told you so," the smile implies), but leaves Brownlow's undoubtedly more concerned facial expression a matter for the sympathetic reader to construct. He effectively differentiates the two old friends by their hairstyles and fashions, for Grimwig wears breaches but has a full head of hair (Brownlow, in contrast, is balding, bespectacled, and dressed in Regency stovepipe trousers and tailcoat). Ridiculing the notion that the child will remain faithful, Grimwig leans back slightly, quite certain that he is correct about Oliver's thanklessness; however, the apprehensive Brownlow leans forward to study the movement of the minute-hand assiduously. The picture creates suspense as to whether Oliver will return, and the text does nothing to alleviate that suspense. Rather, cliff-hanging chapter ending and illustration combine to heighten suspense and propel reader forward into the next chapter, which was originally the second of two in instalment no. 7. At the end of the September 1837 number the pair are still sitting "perseveringly, in the dark parlour: with the watch between them" (111). Thus, the watch and the passage of time and the exhaustion of trust that it implies, is foregrounded in the reader's consciousness by the illustration, which applies the conclusions of both Chapters 14 and 15 — in the original serial leading to a genuine curtain as the reader wonders what steps Brownlow will take to retrieve the lost prodigal and redeem his faith in the boy upon whom he has bestowed his charity and affection.

X. Oliver Trapped by Nancy and Sikes

Left: Eytinge’s Oliver claimed by his affectionate friends. Right: Furniss’s Oliver Trapped by Nancy and Sikes (1867).

Passage Illustrated

[Oliver] was walking along, thinking how happy and contented he ought to feel; and how much he would give for only one look at poor little Dick, who, starved and beaten, might be weeping bitterly at that very moment; when he was startled by a young woman screaming out very loud. "Oh, my dear brother!" And he had hardly looked up, to see what the matter was, when he was stopped by having a pair of arms thrown tight round his neck.

"Don't," cried Oliver, struggling. "Let go of me. Who is it? What are you stopping me for?"

The only reply to this, was a great number of loud lamentations from the young woman who had embraced him; and who had a little basket and a street-door key in her hand.

"Oh my gracious!" said the young woman, "I have found him! Oh! Oliver! Oliver! Oh you naughty boy, to make me suffer such distress on your account! Come home, dear, come. Oh, I've found him. Thank gracious goodness heavins, I've found him!" . . . .

"What the devil's this?" said a man, bursting out of a beer-shop, with a white dog at his heels; "young Oliver! Come home to your poor mother, you young dog! Come home directly."

"I don't belong to them. I don't know them. Help! help!" cried Oliver, struggling in the man's powerful grasp. [Chapter 15, "Showing How Very Fond of Oliver Twist, The Merry Old Jew and Miss Nancy were," 110]

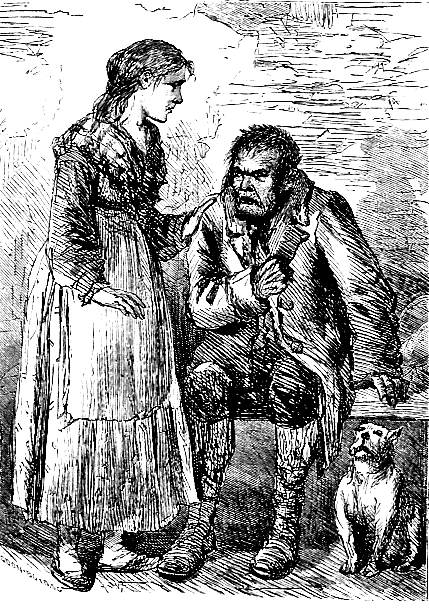

Chapter Sixteen, "Relates What Became of Oliver Twist," involves Oliver's being recaptured by the gang at Fagin's instigation. Furniss's illustration follows the Cruikshank original, introducing the two adult career criminals associated with Fagin's juvenile crew, the loutish Bill Sikes, a housebreaker or burglar, and his common-law wife, Nancy. Although she is a shrewish figure here, the young prostitute with the heart of gold proves instrumental in the authorities' apprehending Monks later in the novel. Furniss describes the brutal burglar as long, lanky, and physically powerful, but does not employ the romanticism that one finds in the contemporary images of Sikes by Kyd: the tankard-carrying tough with the penetrating gaze of Chapter 16, Bill Sikes, or the somewhat less handsome and less polished thug of the Player's cigarette cards, Bill Sikes (1910). Nor does Furniss provide us with the beautiful, wistful, anxious Nancy (see below) of Charles Pears in the 1912 Waverley Edition. Rather, Furniss's overblown, overdressed Nancy is reminiscent of Cruikshank's original frowzy figure in such illustrations as Oliver claimed by his affectionate friends, which, indeed, is the basis for Furniss's version of the scene.

Introducing Nancy and Sykes

Whereas Cruikshank, in collaboration with Dickens himself, elected to realize the scene in which Nancy and Sikes abduct Oliver on his way to Mr. Brownlow's book-seller with a package of books, Mahoney instead introduces the villainous couple prior to their recapturing the boy at Clerkenwell, thereby underscoring the fact that the couple act as Fagin's agents. Thus, Mahoney reveals that, early on, Oliver seems to be the object of behind-the-scenes machinations orchestrated by the master-thief, preparing the reader for the compact between Oliver's half-brother, the malevolent Monks, and Fagin. Neither Cruikshank nor Furniss dwells upon the plot involving Oliver at this point in the story.

Left: Eytinge's Bill Sikes and Nancy show the ill-effects of too much drink while they have been hiding from the authorities (1867). Centre: Darley's highly realistic and technically superior study of the trio as they return to Fagin's hideout, Sikes, Nancy, and Oliver Twist (1888). Right: Kyd's study of Sikes undoubtedly reflects the popular conception of Dickens's thug, Bill Sikes (1910).

Eytinge’s Bill Sikes and Nancy (1867) presents a thoroughly disreputable, ill-kempt, and disconsolate couple after the botched robbery. Darley (1888) full-page lithograph revises in a much more realistic manner the original Cruikshank interpretation of the abduction scene in Sikes, Nancy, and Oliver Twist. In contrast to Mahoney, Furniss revises the abduction scene in Oliver trapped by Nancy and Sikes with a dynamic, baroque treatment of the original, with Sikes suddenly bursting out of the beer-shop and into the street as Nancy grabs Oliver.

The Furniss illustration reflects a fundamental re-thinking of the dramatic scene outside the plebeian beer-house, not so far in distance from the respectable book-seller's at The Green, but socially a very great distance away indeed. Furniss reorganizes the scene so that Oliver's being engulfed by Nancy is foregrounded and Sikes, the enforcer, is caught in the act of entering the scene. Furniss is content not to have so many of the scene's onlookers present (he includes justfour), and to focus instead on the three principals, Nancy (centre), Oliver (left of centre) and, looming large, Sikes to the right. Through the hitching post and glass door (on which "Spirits" appears prominently) Furniss implies rather than graphs the beer-shop from which Sikes enters the square. He also gives prominence to Nancy's house-key which she drops in wrestling with Oliver, a popular token of a young woman's being a prostitute. The pair become the evil antithesis of the kindly samaritans Mr. Brownlow and his housekeeper, Mrs. Bedwin.

XII. The Dodger's Toilet

Left: Eytinge’s Oliver's reception by Fagin and the boys (1867). Right: Furniss’s The Dodger's Toilet (1910).

Passage Illustrated: Thieves' Cant

"Look here!" said the Dodger, drawing forth a handful of shillings and halfpence. "Here's a jolly life! What's the odds where it comes from? Here, catch hold; there's plenty more where they were took from. You won't, won't you? Oh, you precious flat!"

"It's naughty, ain't it, Oliver?" inquired Charley Bates. "He'll come to be scragged, won't he?"

"I don't know what that means," replied Oliver.

"Something in this way, old feller," said Charley. As he said it, Master Bates caught up an end of his neckerchief; and, holding it erect in the air, dropped his head on his shoulder, and jerked a curious sound through his teeth; thereby indicating, by a lively pantomimic representation, that scragging and hanging were one and the same thing.

"That's what it means," said Charley. "Look how he stares, Jack!" [Chapter 18, "How Oliver passed his time in the improving society of his reputable friends," 134]

Commentary

Cruikshank’s Master Bates Explains a Professional Technicality responded to Dickens's November 1837 suggestion for an illustration that alludes to hanging even street-boys for petty theft. The picture shows Oliver's being re-indoctrinated into Fagin's criminal ethos through the companionship of the hardened thieves Charles Bates and Jack Dawkins ("The Artful Dodger"). By the time that Furniss portrayed this once-cautionary scene, even transportation had ceased, and the harsh 18th-century code of justice much ameliorated.

There is no comparable scene of youthful horseplay in the 1871 Household Edition volume because realist Mahoney takes this opportunity to prepare the reader for Fagin's lending Oliver to housebreaker Bill Sikes to assist in the ill-fated robbery at Chertsey in The boy was lying, fast asleep, on a rude bed upon the floor, in Chapter 19, "In Which a Notable Plan is Discussed and Determined On."

Furniss has modelled his illustration of Oliver's reprogramming, then, directly on the Cruikshank original. Despite his being the resident clown of the gang, Charley Bates lives very much in the shadow of his more famous friend, The Artful Dodger, whose wit and personality are markedly more brazen. The November 1837 letter in which Dickens arranges to meet his illustrator to "settle the Illustration" (Letters, I: 329) sheds little light on why the author and artist settled upon this "gallows humour" scene with "Master Bates." However, one may speculate that, having given Jack Dawkins and Fagin centre stage in both Oliver introduced to the respectable Old Gentleman and Oliver amazed at the Dodger's mode of going to work, author and illustrator wanted to showcase the waggish Charley Bates. Certainly, he has not continued to enjoy the celebrity in which his partner-in-crime has basked (thanks in part to Lionel Bart's 1969 musical adapted for the cinema, Oliver!. As the plot thickens and the gang plans to use Oliver to break into the manor house at Chertsey, Surrey, the scene provides necessary welcome comic relief. As Monroe Engle remarks, the Dodger's later "bravado before the court [at his hearing regarding transportation], for example, is moving because it is in the face of heavy consequences. The point is not only that the criminals are threatened by death, but that they are all of them, even the most hardened, aware of the imminence of this threat almost all the time" (106).

Thus, when Charley mimics being hanged by the neck until dead, the usual sentence for even the most trivial of crimes against property prior to the reforms of the 1830s, he is not merely laughing in the face of death, but ridiculing a heartless system. In his horseplay he becomes Dickens's spokesperson for reform. The tom foolery, of course, is Dickens's strategy for creating an ambivalent response in his middle-class readers, who, despite their deploring crimes against property, cannot help but laugh at Charley's antics, in both text and illustration. To fully enjoy Charley's act as the class clown we must become members of the class.

During the period in which Dickens's Newgate Novel is set, criminals were hanged for offences other than murder: in 1820, moreover, a year when nobody was hanged for homicide, 29 people were hanged at Newgate for such lesser crimes as uttering forged notes (twelve instances) and for theft (twelve for robbery or burglary, and five for highway robbery). Charley Bates was quite right, then, about the fate that would probably attend his following the "trade." Ironically, were he to be tried and found guilty of anything other than theft, rape, murder, arson, or forgery, he would most certainly be transported and not hanged until well into the century. Typically in the eighteenth century, crimes against property merited hanging: there were roughly two hundred such crimes, that number only being reduced to just over one hundred in 1823 by the Tory administration of Sir Robert Peel. If the period of the main action of the novel is "Post-Reform Bill," so to speak, Charley's chances of escaping the noose would increase, as, seven years after Peel's initiative, the Liberal administration of Lord John Russellabolished the death sentence for horse stealing and housebreaking. One must assume that, if the story occurs in the early 1830s, Bill Sikes would have hanged as a murderer rather than a mere burglar, but Fagin's hanging for his crimes against property, although on a massive scale, would be less likely — we must assume, therefore, that he is condemned to death for "criminal conspiracy" in the murder of Nancy.

Although Furniss at the turn of the century may not have been acutely aware of the draconian laws which menace Charley and the Dodger on their every expedition, and was not then able to peruse the Dickens-Cruikshank correspondence regarding the choice of this subject, he certainly could have evaluated the strengths and demerits of Cruikshank's original steel engraving. In consequence, the present illustration represents both Furniss's homage to the earlier illustrator and a critical re-thinking. In the original, behind Charley, simulating the noose, is a very stout wooden door which represents enforced isolation. Welcoming any company whatsoever, Oliver gladly becomes the Dodger's bootblack, in thieves' cant, "japanning his trotter-cases" (132). In Furniss's impressionistic revision, the stout door of Oliver's cell all but disappears as the illustrator presents the young thieves not as Fagin's agents but as boozy puppets,and Oliver, now to the side (rather than sandwiched in between them, as in Cruikshank's plate), as the only undistorted human form in the scene. The juxtaposition makes Oliver the normative observer and Charley the entertainer. Under the influence of the large tankards of London ale, the pickpockets jeer at capital punishment, even though Charley's parodying of hanging is not likely to induce Oliver to become an active member of the gang — even though, in fact, that is exactly what he is about to become. So effective is Charley as a comedian that in Furniss's illustration Oliver appears to be highly entertained, whereas in the Cruikshank original he looks somewhat alarmed at the grim fate that awaits these youthful criminals.

XIII. Bill Sikes, Career Criminal

Left: Kyd’s Bill Sikes. Right: Furniss’s Bill Sikes (1910).

The Textual Basis for the Illustration

"Why, what the blazes is in the wind now!" growled a deep voice. "Who pitched that 'ere at me? It's well it's the beer, and not the pot, as hit me, or I'd have settled somebody. I might have know'd, as nobody but an infernal, rich, plundering, thundering old Jew could afford to throw away any drink but water — and not that, unless he done the River Company every quarter. Wot's it all about, Fagin? D—me, if my neck-handkercher an't lined with beer! Come in, you sneaking warmint; wot are you stopping outside for, as if you was ashamed of your master! Come in!"

The man who growled out these words, was a stoutly-built fellow of about five-and-thirty, in a black velveteen coat, very soiled drab breeches, lace-up half boots, and grey cotton stockings which inclosed a bulky pair of legs, with large swelling calves; — the kind of legs, which in such costume, always look in an unfinished and incomplete state without a set of fetters to garnish them. He had a brown hat on his head, and a dirty belcher handkerchief round his neck: with the long frayed ends of which he smeared the beer from his face as he spoke. He disclosed, when he had done so, a broad heavy countenance with a beard of three days' growth, and two scowling eyes; one of which displayed various parti-coloured symptoms of having been recently damaged by a blow.

"Come in, d'ye hear?" growled this engaging ruffian. [Chapter 13, "Some New Acquaintances are introduced to the Intelligent Reader; Connected with whom, Various Pleasant Matters are Related, Appertaining to this History," 87-88]

Left: J. Clayton Clarke's 1890 portrait "Bill Sikes. Right: James Mahoney's "You are still on the scent, are you, Nancy?".

Part of Dickens's intention for Sikes seems to have been to use him to debunk the romance of the dashing professional thief established by such figures as Henry Fielding's Jonathan Wilde, William Harrison Ainsworth's Jack Shepherd, Edward Bulwer Lytton's Paul Clifford, and — ultimately — John Gay's rakish highwayman Macheath in The Beggar's Opera (1728).

George Cruikshank introduced the surly burglar Bill Sikes.As the gang's chief outside contractor Sikes together with his doxy, Nancy, undertakes to recapture Oliver after his apprehension in the abortive robbery of book-browsing Mr. Brownlow. Until he becomes unnerved after murdering Nancy, Sikes is much the same throughout the novel: brutal, determined, and without compassion or imagination. Although he does not include the burglar's constant companion, the "white-coated, red-eyed dog" the ill-treated cur Bull's-eye, Furniss has modelled his full-length portrait of the scowling Sikes on both realisations by Cruikshank and Mahoney, notably the thug in the dingy white beaver and long greatcoat in "You are on the scent, are you, Nancy?" (see below). Both Sikes attempting to destroy his dog and The Last Chance also offered Furniss workable models, both of which, of course, are directly based on Dickens's original descriptions of the brutal housebreaker and, ultimately, murderer.

In the original serial illustration introducing Sikes, Oliver claimed by his affectionate friends, Cruikshank depicts the tall, unshaven thug as he grabs Oliver in the back streets of Clerkenwell on his way to return Mr. Brownlow's books. There is no comparable scene in the 1871 Household Edition volume; rather, avoiding a scene already competently rendered by Cruikshank, Mahoney shows Oliver being pursued as a pickpocket by a mob.

Cruikshank, Dickens's official illustrator for Oliver Twist in the 1837-9 serial, depicts the housebreaker as the sordid, lower-class villain out of contemporary melodrama, the figure whom Felix Octavius Carr Darley describes in his series of Character Sketches from Dickens (1888) is once again much more of an individual (despite his characteristic long face and white top hat) than a type. In the chapter 22 illustration which depicts Oliver's being surprised and shot at as soon as he has entered to house that Sikes is attempting to rob, The Burglary, Cruikshank depicts the burglar in a framed portrait, as an apparently helpless Sikes watches the unfolding scene with interest. Effectively rendered, Cruikshank's ruffian is unshaven, unkempt, and full-faced. Selecting an equally dramatic moment in the story, Darley depicts Sikes in action, rather than as a static figure, whereas in the Diamond Edition of 1867, Sol Eytinge, Jr., in Bill Sikes and Nancy (see below) captures the disreputable couple's desperation and despondency after the botched robbery at Chertsey. Taking a little more pity on the down-and-out couple, in the Household Edition, the realist Mahoney focuses on Nancy's tenderness for the exhausted Skies, whom she tends as if he were her child in Then, stooping over the bed, she kissed the robber's lips (Chapter 39) — a highly ironic scene, given Sikes's subsequent treatment of the woman whom he believes has betrayed him and Fagin's gang. In the 1890 collection of Dickens's characters, The Characters of Charles Dickens pourtrayed in a series of original watercolours by "Kyd", J. Clayton Clarke romantizes the ill-shaven thug with the swaggering gait and penetrating gaze. Perhaps the quintessential realisation of Fagin's burly associateis that by Felix Octavius Carr Darley in his Character Sketches from Dickens.

Actors who have portrayed Sikes on film include Robert Newton in the 1948 David Lean film, Oliver Reed in the 1968 musical Oliver! (replacing Danny Sewell from the original stage production), and Tim Curry (1982), Robert Loggia (voice, 1988), Michael McAnallen (1995), David O'Hara (1997), Andy Serkis (1999), Jamie Foreman (2005), Tom Hardy (2007), Burn Gorman (2009), Steven Hartley (2009), Shannon Wise (2010), Jake Thomas (2011), and Anthony Brown (2012).

XIV. Making Oliver Take Part in a Burglary

Furniss’s Oliver in the Grip of Sikes (1910).

Context of the Illustration

"Come here, young 'un; and let me read you a lectur', which is as well got over at once."

Thus addressing his new pupil, Mr. Sikes pulled off Oliver’s cap and threw it into a corner; and then, taking him by the shoulder, sat himself down by the table, and stood the boy in front of him.

"Now, first: do you know wot this is?" inquired Sikes, taking up a pocket-pistol which lay on the table.

Oliver replied in the affirmative.

"Well, then, look here," continued Sikes. "This is powder; that 'ere's a bullet; and this is a little bit of a old hat for waddin'." [Chapter 20, "Wherein Oliver is Delivered over to Mr. William Sikes," 152]

Commentary

In this scene the burglars and Nancy terrify Oliver into cooperating to rob a mansion at Chertsey in Surrey, a house that Flash Toby Crackit has been "casing" on behalf of the gang. The illustration, which is another instance of Oliver's being menaced by adults, repeats the themes of Oliver refuses to be Bound over to the Sweep (Chapter 3), but here Furniss introduces a direct threat of violence should Oliver exhibit any signs of non-compliance: the two adult career criminals, Sikes and Nancy, threaten the terrified, writhing boy — Nancy with a reproving finger pointed at Oliver, and a Neanderthal-like Sikes with a small flintlock pistol, its barrel only inches from Oliver's face. Later illustrator Kyd depicts a rakish Sikes as a tankard-carrying tough with fitting clothes and a penetrating gaze, as in Chapter 16, Bill Sikes (see above), rather than a grim-faced bully. Nor does Furniss provide us with the beautiful, wistful, anxious Nancy of Charles Pears in the 1912 Waverley Edition (see below). Furniss's overblown, overdressed Nancy is reminiscent of Cruikshank's original frowzy figure in such illustrations as Oliver claimed by his affectionate friends, which offered Furniss a viable model for Nancy in bonnet and shawl, hardly the delicate beauty of Pears' romanticized version of the young prostitute.

Whereas Cruikshank, working in collaboration with Dickens himself, elected to depict the scene in which Nancy and Sikes abduct Oliver on his way to Mr. Brownlow's book-seller with a package of books, Oliver claimed by his affectionate friends, Mahoney instead introduces the villainous couple prior to their recapturing the boy at Clerkenwell, underscoring the fact that the couple are acting as Fagin's agents in "You are on the scent, are you, Nancy?" (Chapter 15). Then, in the Household Edition Mahoney depicts Oliver and Sikes on the way to the advanced post for the robbery in Sikes, with Oliver's hand still in his, softly approached the low porch (Chapter 21, "The Expedition" — see below). Oliver in this instance is clearly Sikes's pawn, but Furniss offers the scene of Sikes's threatening Oliver to exonerate the boy of any taint of criminality as he is acting strictly under duress.

Although in the 1867 Diamond Edition Sol Eytinge presents a thoroughly disreputable, ill-kempt, and disconsolate couple in his dual character study entitled Bill Sikes and Nancy, realising them as they appear after the botched robbery, in Chapter 39, Darley in his 1888 Character Sketches from Dickens, revises in a much more realistic manner the original Cruikshank interpretation of the abduction scene in Sikes, Nancy, and Oliver Twist.

Above: Mahoney's Household Edition illustration of Sikes's dragging an unwilling Oliver into a life of crime in Sikes, with Oliver's hand still in his, softly approached the low porch (1871).

XV. The Botched Burglary at the Maylies' home in Chertsey

Left: Cruikshank's original version of The Burglary (January 1838). Right: Furniss’s The Burglary (1910).

Passage Illustrated

In the short time he had had to collect his senses, the boy had firmly resolved that, whether he died in the attempt or not, he would make one effort to dart upstairs from the hall, and alarm the family. Filled with this idea, he advanced at once, but stealthily.

"Come back!" suddenly cried Sikes aloud. "Back! back!"

"Scared by the sudden breaking of the dead stillness of the place, and by a loud cry which followed it, Oliver let his lantern fall, and knew not whether to advance or fly.

The cry was repeated — a light appeared — a vision of two terrified half-dressed men at the top of the stairs swam before his eyes — a flash — a loud noise — a smoke — a crash somewhere, but where he knew not, — and he staggered back. [Chapter 22, "The Burglary," 166]

Commentary

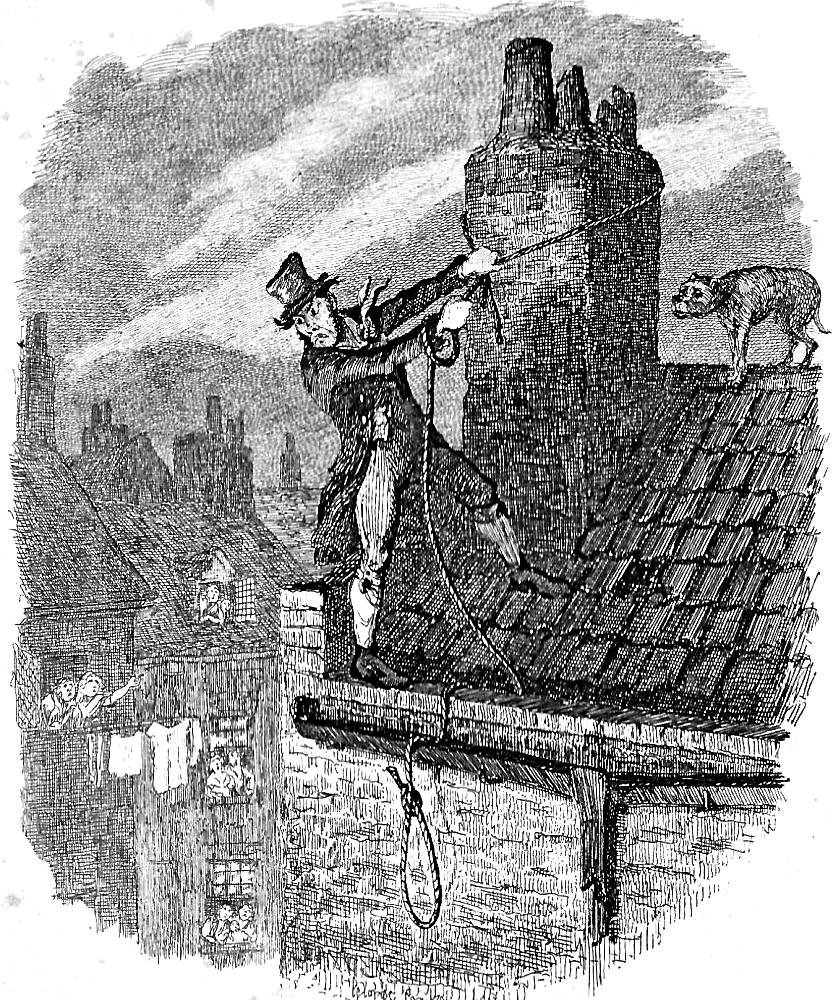

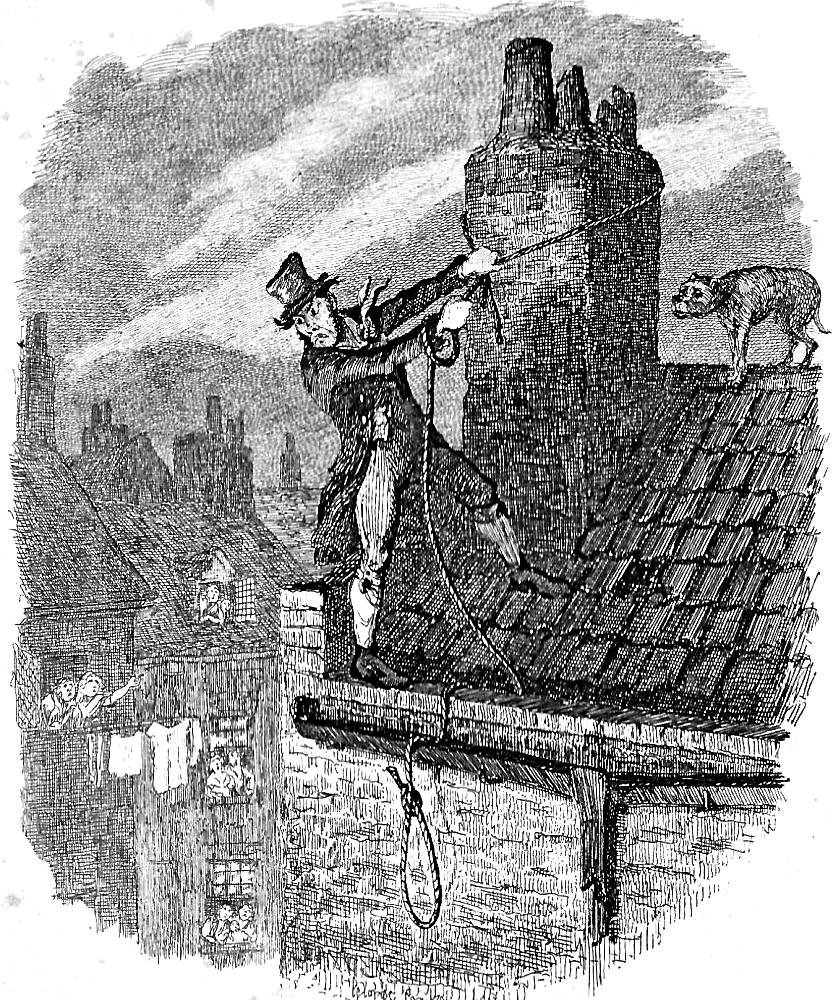

In the January 1838 number of Bentley's Miscellany Cruikshank depicted yet another turning point in Oliver's life as the boy fails to admit the gang to the house. In Cruikshank's dramatic realisation of The Burglary, the reader encounters the scene of Oliver's discovery by the servants shortly after he had climbed in through a small window in at the Maylies' home in suburban Chertsey. In contrast, Furniss radically reconstructs the Cruikshank illustration, for by throwing Oliver off the central axis, he injects considerable emotion into both the terrified servants at the rear and wounded Oliver in the foreground while transforming Sikes's head from a framed portrait to a trophy mounted on the wall. The botched robbery is crucial to the plot because it transfers Oliver once again from the grip of the gang to those associated with his mother; before, the botched pickpocketing expedition had resulted in Oliver's being placed in Mr. Bownlow's custody; now, left for deadin a ditch, Oliver is recalled to life and taken in by the Maylies — his mother's family.

Although Cruikshank depicts the housebreaker Bill Sikes as the sordid, lower-class villain out of contemporary melodrama, the figure whom Darley in his 1888 series of Character Sketches from Dickens describes is much more of an individual (despite his characteristic long face and white top hat derived directly from Cruikshank) than a type. In the chapter 22 illustration which depicts Oliver's being surprised and shot at as soon as he has entered the Chertsey house that Sikes is attempting to rob, Cruikshank minimizes the previously intimidating bulk of the notorious housebreaker by confining him to a mere facial likeness in the frame window five-and-a-half feet off the ground outside — in a framed portrait, so to speak — as Sikes watches the unfolding scene with interest and relative impotence as he seems powerless to intervene to save Oliver or assault the servants who are discharging firearms. Effectively rendered, Cruikshank's ruffian is unshaven, unkempt, and full-faced — but the small window through which he peers would prevent him from firing his own weapon on the two servants, let alone haul Oliver out if harm's way by the collar in the text on the page facing the steel-engraving, which intensifies the suspense at the end of the monthly part, as the author reports the protagonist's sensations of being hauled up through the window, dragged across the ground, and left to die in a ditch. The same improbability associated with the window is apparent in Furniss's highly-charged rendition of the same dramatic moment.