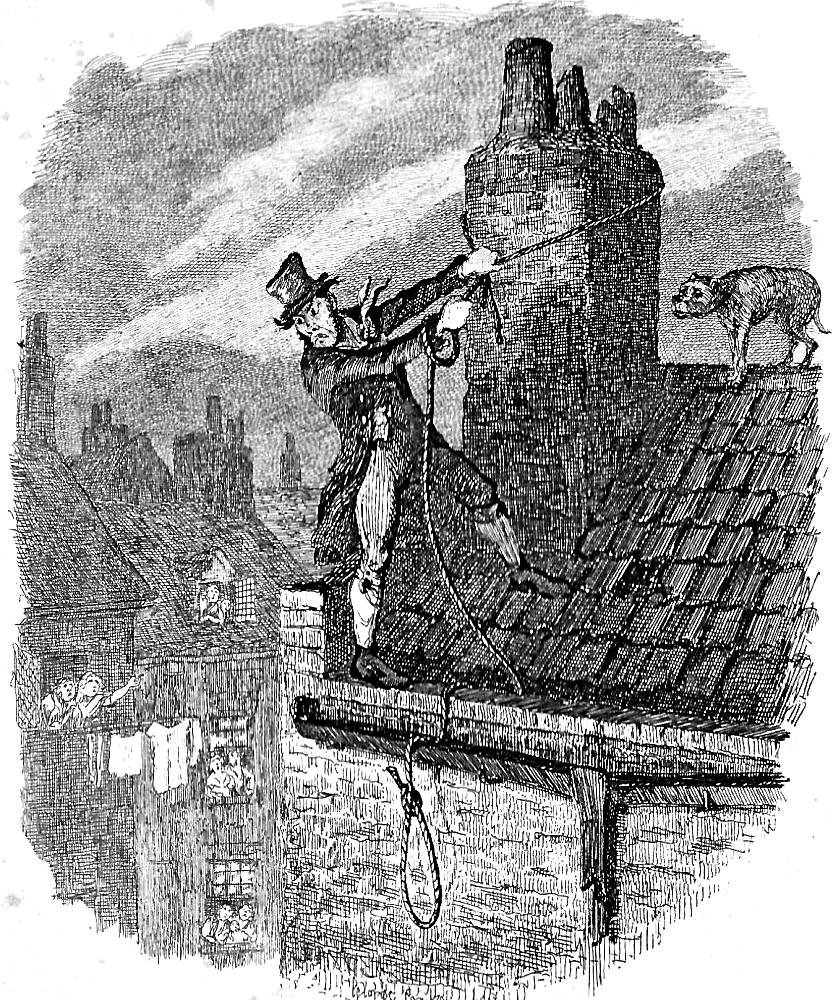

The last chance — The End of Sikes, the twenty-second steel engraving and later watercolour for Charles Dickens's The Adventures of Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress, published in Volume III by Richard Bentley after its November 1838 appearance in Bentley's Miscellany, Chapter L. 4 ½ by 3 ⅝ inches (11.8 cm by 10.1 cm), vignetted, facing page 292 in the 1846 edition (originally leading off the third volume in the three-volume edition of 9 November 1838). Cruikshank's own 1866 watercolour, commissioned by F. W. Cosens, is the basis for the 1903 chromolithograph. [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Passage Illustrated: Bulls'Eye dogs Sikes to His Death

Near to that part of the Thames on which the church at Rotherhithe abuts, where the buildings on the banks are dirtiest and the vessels on the river blackest with the dust of colliers and the smoke of close-built low-roofed houses, there exists the filthiest, the strangest, the most extraordinary of the many localities that are hidden in London, wholly unknown, even by name, to the great mass of its inhabitants.

. . . . In Jacob's Island, the warehouses are roofless and empty; the walls are crumbling down; the windows are windows no more; the doors are falling into the streets; the chimneys are blackened, but they yield no smoke. Thirty or forty years ago, before losses and chancery suits came upon it, it was a thriving place; but now it is a desolate island indeed. The houses have no owners; they are broken open, and entered upon by those who have the courage; and there they live, and there they die. They must have powerful motives for a secret residence, or be reduced to a destitute condition indeed, who seek a refuge in Jacob’s Island. [Chapter L, "The Pursuit and Escape," pp. 285-286]

The man had shrunk down, thoroughly quelled by the ferocity of the crowd, and the impossibility of escape; but seeing this sudden change with no less rapidity than it had occurred, he sprang upon his feet, determined to make one last effort for his life by dropping into the ditch, and, at the risk of being stifled, endeavouring to creep away in the darkness and confusion.

Roused into new strength and energy, and stimulated by the noise within the house which announced that an entrance had really been effected, he set his foot against the stack of chimneys, fastened one end of the rope tightly and firmly round it, and with the other made a strong running noose by the aid of his hands and teeth almost in a second. He could let himself down by the cord to within a less distance of the ground than his own height, and had his knife ready in his hand to cut it then and drop.

At the very instant when he brought the loop over his head previous to slipping it beneath his arm-pits, and when the old gentleman before-mentioned (who had clung so tight to the railing of the bridge as to resist the force of the crowd, and retain his position) earnestly warned those about him that the man was about to lower himself down — at that very instant the murderer, looking behind him on the roof, threw his arms above his head, and uttered a yell of terror.

"The eyes again!" he cried in an unearthly screech.

Staggering as if struck by lightning, he lost his balance and tumbled over the parapet. The noose was on his neck. It ran up with his weight, tight as a bow-string, and swift as the arrow it speeds. He fell for five-and-thirty feet. There was a sudden jerk, a terrific convulsion of the limbs; and there he hung, with the open knife clenched in his stiffening hand.

The old chimney quivered with the shock, but stood it bravely. The murderer swung lifeless against the wall; and the boy, thrusting aside the dangling body which obscured his view, called to the people to come and take him out, for God's sake.

A dog, which had lain concealed till now, ran backwards and forwards on the parapet with a dismal howl, and collecting himself for a spring, jumped for the dead man’s shoulders. Missing his aim, he fell into the ditch, turning completely over as he went; and striking his head against a stone, dashed out his brains. [Chapter L, "The Pursuit and Escape," pp. 292-293]

Commentary: High Drama at Toby Crackit's Hideout

Cruikshank here is without equal in his dramatic realisation of Sikes's final efforts to escape punishment for murdering Nancy. The serial plate effectively realizes Sikes's heroic end as Cruikshank depicts the powerfully built, thirty-five-year-old burglar coolly assessing how he may yet elude capture by daring to drop from a rooftop on Jacob's Island. Scheming to avoid detection and capture, Sikes hopes to throw the authorities off the scent by returning to the vicinity of the crime, planning to lay low for a few days in fellow-burglar Toby Crackit's safe-house on Jacob's Island (only truly an island in those days when the tide was in) before slipping across the Channel to start a new life (or at least a new criminal career) in France. In Dickens's England, Tony Lynch notes that the modern tourist, searching the London grid, will be hard pressed to find revenants of Jacob's Island, which was a byword for vice, crime, and deplorable sanitation in Dickens's time.

Jacob's Island once lay a mile to the east of London Bridge on the south side of the River Thames. The area has long since been 'improved away' and now forms that part of Bermondsley bounded by Mill Street, Jacob Street and George Row. In the 1830s the island — so named because it was cut off at high tide by a stretch of water known as Folly Ditch — was a maze of narrow, muddy alleyways between grim tenement buildings . . . . [Lynch 122]

However, the squalid slum retained something of its original character even at the turn of the century with its wooden, two-storey houses assembled from material left over from wharf construction and ship-building. In the 1830s it rivalled Field Lane as a centre of vice and crime — and is therefore the logical locale for Toby Crackit's safe-house and Sikes's demise. The multiple chimneys of the safehouse at Jacob's Island prove instrumental in Sikes's accidental hanging.

With all the cockiness of a young writer who thought he knew a great deal about illustration, Dickens had written to Cruikshank "that the scene of Sikes' escape will not do for illustration. It is so very complicated, with such a multitude of figures, such violent action, and torch-light to boot, that a small plate could not take in the slightest idea of it." Fortunately for generation after generation of readers of the novel, the illustrator did not heed Dickens's warning. According to Robert L. Patten in his 1996 biography George Cruikshank's Life, Times, and Art, Volume 2: 1835-1878, the illustrator

chose to ignore Dickens's advice that the death of the housebreaker could not be represented (cover). The "multitude of figures" is indicate by the onlookers leaning out of tenement windows. The "torch-light" is suggested by the illumination picking out the wall, the chimney, and Bill's leg and features. The "violent action" is recapitulated by the structure, a collision of verticals with diagonals, and by the the imagery, which moves from the background of scudding clouds and frantically gesturing neighbors to the foregrounded tiles of the vertiginous roof thrust forward onto the picture's front plane, up to Bull's-eye perched precariously on the apex of the roof, around the chimney and down through the rope to the ominous dangling noose and the strong T of the guttering. The streaming tails of Bill's Belcher neckerchief identify the wind whipping past (a trick Cruikshank had used in plate IV of The Progress of a Midshipman) and signify that potential for hanging which has been applied so often to so many characters in this parable. The abrupt recession on the houses behind, whose distance is exaggerated by their diminution, reads as an analogue of the steep drop into Folly Ditch below. "the tiles of the roof," Swinburne said, "and the stack of chimneys and glimmering walls and lattices and the smoke-swept sky . . . give the fittest and the fearfullest relief to the imminence of [Sikes's] doom" [Charles Dickens, 1913, p. 13]. At the intersection of these dizzying, energized spaces, the housebreaker balances, legs and arms straining to hold himself stable by means of the very hemp that will shortly terminate his frantic activity. The whole plate is a bravura pictorial narration, fully in accord with Dickens's vivid prose yet independent and supplementary, a similar story told by different means. The preliminary drawing is captioned as Cruikshank saw the scene verbally: "Sykes endeavouring to escape by fixing the rope around the stock of chimnies by which he is killed." ["Oliver Twist and the 'Apples of Discord'," pp. 87-88]

Other illustrators have presented more satisfactory and consistent images of Sikes's companion and ultimately his Nemesis, Bull's-Eye. Harry Furniss in his 1910 lithographic series offers three illustrations depicting the sensational events in the final days of the Hogarthian blackguard: the dark plate The Death of Nancy, the humorous taproom scene at The Eight Bells, Hatfield, The Flight of Bill Sikes, and the peculiar rendition of Sikes's hanging in which Sikes himself does not appear in the frame at all, The End of Sikes (see below). The parallel 187I Household Edition illustration depicts Sikes's raging at his pursuers from the roof top of the gang's rookery with And creeping over the tiles, looked over the low parapet. In contrast, Dickens's chief American illustrator, Sol Eytinge, Junior, offers a portrait of the dissolute burglar and his bedraggled doxy in Chapter 39, but has no illustrations inserted into the chapters in which Sikes murders Nancy, flees, and in a sensational scene worthy of dramatist Dion Boucicault falls to his death in a final bid to cheat the law.

With a sharper eye for detail than his illustrator's, Dickens undoubtedly noticed that the parapet over which Sikes stares at the mob below is missing from the illustration, that Cruikshank (perhaps to show all of the malefactor's face and form) has substituted the strong horizontal of a rain-gutter for the parapet, that the case-knife Sikes intends to employ is not evident, — and that the illustrator, probably to avoid cluttering the composition, has deprived Sikes of enough rope to hang himself, let alone get himself down from the roof. Nevertheless, whereas Mahoney's Sikes almost snarls over the parapet, Cruikshank's coolly appraises both the people below and his situation as he braces himself for his descent — unaware that Bull's-Eye is on the other side of the chimney. Even as Sikes believes that he is going to elude his pursuers, the reader apprehends through the facing page of text that Sikes, suddenly unmanned by thinking that he sees Nancy's eyes, grossly miscalculates at the critical juncture and inadvertently hangs himself. Cruikshank's figure of the redoubtable rogue is infinitely better conceived than that of Sikes's dog. Moreover, Cruikshank's conception of the scene, incorporating onlookers at four windows below Sikes, is charged with energy and conveys a sense of Sikes's being high above the surrounding houses. Unphased by the danger of his precarious position as he trusts to the stoutness of his legs and arms, Sikes assesses the spot that he should make for when he jumps. The wind blows back his neckerchief, smoke scuds past him, and the background buildings are lightly rendered or obscured (suggesting the obscuring effects of fog and smoke), contrasting the sharply realised, stalwart figure on the rooftop. To the last Sikes is undeterred and, despite his brutal nature, admirable in his determination. Juxtaposed against the pillar-like Sikes is the centrally positioned noose, which Sikes appears not to consider as he looks down.

Cruikshank carefully provides visual continuity by dressing Sikes in much the same clothing throughout, and consistently pairs Sikes with his dog even in this final scene. Mahoney in the Household Edition, on the other hand, seems to have chosen to avoid depicting Sikes in these later chapters, for in the 1871 volume Sikes is clearly seen only in this rooftop scene after his earlier appearances as an associate of Fagin: "You are on the scent, are you, Nancy?" and the robbery scenes at Chertsey, Sikes, with Oliver's hand still in his, softly approached the low porch and "Directly I leave go of you, do your work. Hark!". The Sikes in his ultimate appearance in Mahoney's sequence rages at the mob below, but the illustrator offers a closeup that precludes showing the onlookers or attempting to indicate the height from which Sikes surveys the scene, so that one can appreciate Cruikshank's middle-distance perspective that allows us to see eight denizens of Jacob's Island pointing upward and leaning out of their windows to getter a better view of the sensational chase scene as the authorities close in upon the murderer. Cruikshank perhaps afterwards realized that this is one of the most dramatic scenes in the novel, and accordingly selected it as one of the eleven vignette scenes on the 1846 monthly wrapper that he designed for Chapman and Hall. To the Victorian reader Sikes's accidental self-hanging would have been an affirmation of divine intervention in the affairs of humanity rather than mere coincidence or miscalculation.

Relevant Illustrations from the serial edition wrapper (1846), Household Edition (1871), and Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910)

Left: George Cruikshank's depiction of Sikes's death, detail from The Monthly Wrapper (31 December 1845). Centre: James Mahoney's And creeping over the tiles, looked over the low parapet (1871). Right: Harry Furniss's Charles Dickens Library Edition illustration The End of Sikes (1910). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Related Material

- Oliver Twist as a Triple-Decker

- Oliver untainted by evil

- Like Martin Chuzzlewit, it agitates for social reform

- Oliver Twist Illustrated, 1837-1910

Scanned images and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. "George Cruikshank." Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State U. P., 1980. Pp. 15-38.

Darley, Felix Octavius Carr. Character Sketches from Dickens. Philadelphia: Porter and Coates, 1888.

Davies, Philip. "Warren of Sunless Courts." Lost London, 1870-1945. Croxley Green, Hertfordshire: Transatlantic, 2009. Pp. 258- 260.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. The Adventures of Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Bradbury and Evans; Chapman and Hall, 1846.

_______. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 55 vols. Illustrated by F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. New York: Sheldon and Co., 1865.

_______. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Diamond Edition. 14 vols. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

_______. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 22 vols. Illustrated by James Mahoney. London: Chapman and Hall, 1871. Vol. I.

_______. The Adventures of Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. 3.

Forster, John. "Oliver Twist 1838." The Life of Charles Dickens. Ed. B. W. Matz. The Memorial Edition. 2 vols. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1911. Vol. 1, book 2, chapter 3. Pp. 91-99.

Grego, Joseph (intro) and George Cruikshank. "The last chance." Cruikshank's Water Colours. [27 Oliver Twist illustrations, including the wrapper and the 13-vignette title-page produced for F. W. Cosens; 20 plates for William Harrison Ainsworth's The Miser's Daughter: A Tale of the Year 1774; 20 plates plus the proofcover the work for W. H. Maxwell's History of the Irish Rebellion in 1798 and Emmett's Insurrection in 1803]. London: A. & C. Black, 1903. OT = pp. 1-106]. Page 92.

Kitton, Frederic G. "George Cruikshank." Dickens and His Illustrators: Cruikshank, Seymour, Buss, "Phiz," Cattermole, Leech, Doyle, Stanfield, Maclise, Tenniel, Frank Stone, Topham, Marcus Stone, and Luke Fildes. 1899. Rpt. Honolulu: U. Press of the Pacific, 2004. Pp. 1-28.

Lynch, Tony. "Jacob's Island, London." Dickens's England: An A-Z Tour of the Real and Imagined Locations. London: Batsford, 2012. Pp. 122.

Patten, Robert L. George Cruikshank's Life, Times, and Art, Volume 2: 1835-1878. Cambridge: The Lutterworth Press, 1996.

Created 17 November 2017 Last modified 15 January 2022