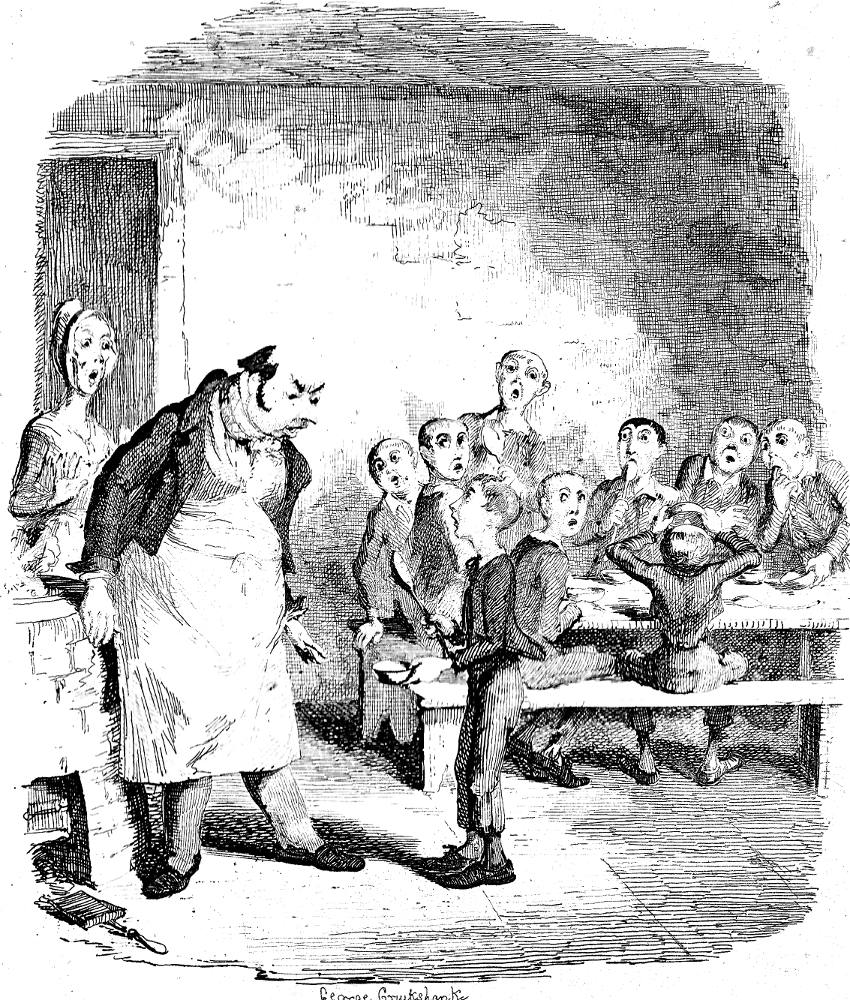

"Uncaptioned Headpiece for Chapter One," James Mahoney's interpretation of George Cruikshank's frontispiece for Dickens's The Adventures of Oliver Twist, Household Edition, page 1. 1871. Wood engraving by the Dalziels, 10.6 cm high by 13.6 cm wide. In the barren refectory of the parish workhouse, Oliver, egged on by the other eight waifs in the background, entreats the master of the workhouse for another helping of gruel — much to the dismay of the workhouse's matron (upper centre). Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite it in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated

For the first six months after Oliver Twist was removed, the system was in full operation. It was rather expensive at first, in consequence of the increase in the undertaker's bill, and the necessity of taking in the clothes of all the paupers, which fluttered loosely on their wasted, shrunken forms, after a week or two's gruel. But the number of workhouse inmates got thin as well as the paupers; and the board were in ecstasies.

The room in which the boys were fed, was a large stone hall, with a copper at one end: out of which the master, dressed in an apron for the purpose, and assisted by one or two women, ladled the gruel at mealtimes. Of this festive composition each boy had one porringer, and no more — except on occasions of great public rejoicing, when he had two ounces and a quarter of bread besides.

The bowls never wanted washing. The boys polished them with their spoons till they shone again; and when they had performed this operation (which never took very long, the spoons being nearly as large as the bowls), they would sit staring at the copper, with such eager eyes, as if they could have devoured the very bricks of which it was composed; employing themselves, meanwhile, in sucking their fingers most assiduously, with the view of catching up any stray splashes of gruel that might have been cast thereon. Boys have generally excellent appetites. Oliver Twist and his companions suffered the tortures of slow starvation for three months: at last they got so voracious and wild with hunger, that one boy, who was tall for his age, and hadn't been used to that sort of thing (for his father had kept a small cook-shop), hinted darkly to his companions, that unless he had another basin of gruel per diem, he was afraid he might some night happen to eat the boy who slept next him, who happened to be a weakly youth of tender age. He had a wild, hungry eye; and they implicitly believed him. A council was held; lots were cast who should walk up to the master after supper that evening, and ask for more; and it fell to Oliver Twist.

The evening arrived; the boys took their places. The master, in his cook's uniform, stationed himself at the copper; his pauper assistants ranged themselves behind him; the gruel was served out; and a long grace was said over the short commons. The gruel disappeared; the boys whispered each other, and winked at Oliver; while his next neighbours nudged him. Child as he was, he was desperate with hunger, and reckless with misery. He rose from the table; and advancing to the master, basin and spoon in hand, said: somewhat alarmed at his own temerity:

"Please, sir, I want some more."

The master was a fat, healthy man; but he turned very pale. He gazed in stupified astonishment on the small rebel for some seconds, and then clung for support to the copper. The assistants were paralysed with wonder; the boys with fear.

"What!" said the master at length, in a faint voice.

"Please, sir," replied Oliver, "I want some more."

[Chapter 2, "Treats of Oliver Twist's Growth, Education, and Board," p. 6-7]

Commentary

"Oliver Asks for More," James Mahoney's first regular illustration for Dickens's The Adventures of Oliver Twist, Household Edition, page 1. 1871. Wood engraving by the Dalziels, 10.6 cm high by 13.6 cm wide. In a north of England workhouse, Oliver, acting as the spokesman for the other inmates of the instiution, dares to request an additional helping of gruel from the "fat, healthy" (7) master of the workhouse. The well-fed functionary stares in disbelief, as in the original George Cruikshank illustration for Bentley's Miscellany in February 1837.

By now, this confrontational scene in the workhouse in the initial (February 1837) number of The Adventures of Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress is familiar to even non-English speakers as a result of dramatisations on stage, television, and film, and even in such cartoons as Oliver Asks for a Doggy Bag, even though few would identify it with an obscure Victorian periodical entitled Bentley's Miscellany, in which the novel first appeared in twenty-four monthly instalments, each with a single-page steel engraving by noted caricaturist George Cruikshank.

Born in the workhouse where his mother died shortly afterwards, for all but the first of the first nine years of life Oliver has been raised in Mrs. Mann's baby farm; on his ninth birthday, under the tutelage of the self-important parish Beadle, Mr. Bumble, the boy now returns to "learn a useful trade" (picking oakum, in fact — hardly a skill), if he does not succumb to the workhouse regimen, which tends to starve boys to death. In Mahoney's redrafting the celebrated scene for the Household Edition in 1871, a rake-thin Oliver innocently gestures towards the fat master with his bowl. Whereas in the original 1837 steel engraving the overfed "master" scowls at the temerity of the scrawny waif, while the eight other survivors of the starving system look on in suspense, Mahoney has turned the master's face away from the reader, and has repositioned the matron, who now expresses merely modest astonishment (centre rear) at Oliver's unorthodox behaviour. However, the steel engraving has subtleties that the woodblock-engraving necessarily lacks, and the overall effect of the Mahoney illustration is that it is derivative rather than original, relying for its full meaning not merely on a textual passage in the next chapter, but on the reader's knowledge of the original illustration.

Illustrations from the Serial (1837) and the Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910)

Left: Harry Furniss's Charles Dickens Library Edition illustration (1910) Starvation in the Workhouse. Right: George Cruikshank's original version of Oliver's Asking for More [Click on images to enlarge them.]

References

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Darley, Felix Octavius Carr. Character Sketches from Dickens. Philadelphia: Porter and Coates, 1888.

Dickens, Charles. Oliver Twist. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Bradbury and Evans; Chapman and Hall, 1846.

Dickens, Charles. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 55 vols. Il. F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. New York: Sheldon and Co., 1865.

Dickens, Charles. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Diamond Edition. 18 vols. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

Dickens, Charles. The Adventures of Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. Illustrated by James Mahoney. London: Chapman and Hall, 1871.

Dickens, Charles. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Charles Dickens Library Edition. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. London: Educational Book Company, 1910.

Bibliography: New Publication

Hunger and Famine in the Long Nineteenth Century. Ed. Gail Turley Houston. London: Routledge, 2022.

Created 22 November 2014

Last modified 21 May 2022