Fagin

Charles Pears

1912

11.7 x 9 cm, framed

Fourth and final illustration for The Adventures of Oliver Twist in Oliver Twist, Centenary Edition (1912), facing p. 304.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[Victorian Web Home —> Visual Arts —> Illustration —> Charles Pears]

Fagin

Charles Pears

1912

11.7 x 9 cm, framed

Fourth and final illustration for The Adventures of Oliver Twist in Oliver Twist, Centenary Edition (1912), facing p. 304.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

He had spoken little to either of the two men, who relieved eachother in their attendance upon him; and they, for their parts, made no effort torouse his attention. He had sat there, awake, but dreaming. Now, he started up,every minute, and with gasping mouth and burning skin, hurried to and fro, insuch a paroxysm of fear and wrath that even they — used to such sights— recoiled from him with horror. He grew so terrible, at last, in all thetortures of his evil conscience, that one man could not bear to sit there, eyeinghim alone; and so the two kept watch together.

He cowered down upon his stone bed, and thought of the past. He had been wounded with some missiles from the crowd on the day of his capture, and his head was bandaged with a linen cloth. His red hair hung down upon his bloodless face; his beard was torn, and twisted into knots; his eyes shone with a terrible light; his unwashed flesh crackled with the fever that burnt him up. Eight — nine — then. If it was not a trick to frighten him, and those were the real hours treading on each other's heels, where would he be, when they came round again! Eleven! Another struck, before the voice of the previous hour had ceased to vibrate. At eight, he would be the only mourner in his own funeral train; at eleven —

Those dreadful walls of Newgate, which have hidden so much misery and such unspeakable anguish, not only from the eyes, but, too often, and too long, from the thoughts, of men, never held so dread a spectacle as that. The few who lingered as they passed, and wondered what the man was doing who was to be hanged to-morrow, would have slept but ill that night, if they could have seen him. [Chapter 52, originally "The Jew's Last Night Alive" — subsequently re-entitled in the Centenary Edition "Fagin's Last Night Alive," pp. 306-307]

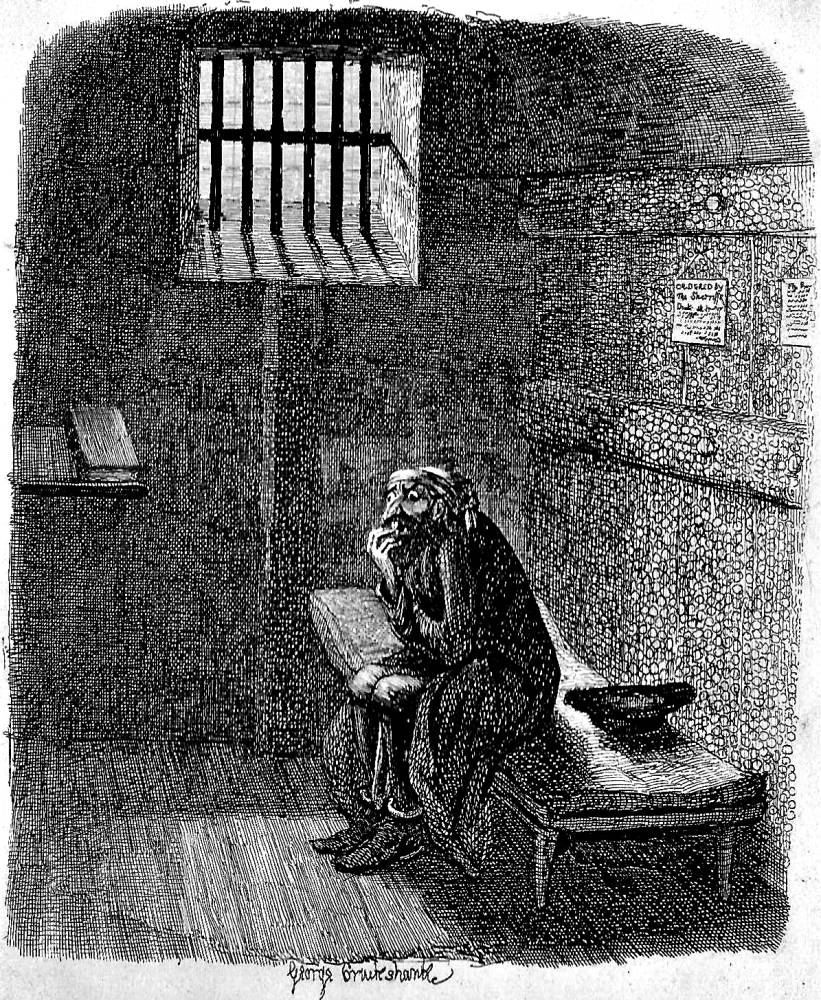

Dickens's original illustrator, George Cruikshank in Bentley's Miscellany developed the iconic image of the terrified, obsessed Fagin in the condemned cell at Newgate Prison supposedly by looking in the mirror. All subsequent interpretations of this scene, including this one in the 1912 Centenary Edition and Furniss's in the 1910 Charles Dickens Library Edition are directly derived from Cruikshank's Fagin in the condemned Cell Part 23, March 1839.

Aware that one of the sordid, lower-class villains — Sikes, or Fagin — would finish the novel in Newgate Prison, Cruikshank did multiple studies of both criminals in the condemned cell. Eventually, of course, he realised that the solitary prisoner facing execution would be Fagin; however, he struggled to find the right pose and facial expression for the condemned man who, in Dickens's text, experiences a great range of reactions to his own impending death. Although he later repudiated the story, Cruikshank later recounted how his own facial expression led to his telling study of Fagin in which the disconsolate prisoner

is seen biting his finger-nails and suffering the tortures of remorse and chagrin [;] Horace Mayhew took an opportunity of asking [the illustrator] by what mental process he had conceived such an extraordinary notion; and his answer was, that he had been labouring at the subject for several days, but had not succeeded in getting the effect he desired. At length, beginning to think the task was almost hopeless, he was sitting up in bed one morning, with his hand covering his chin and tips of his fingers between his lips, the whole attitude expressive of disappointment and despair, when he saw his face in a chevalier-glass which stood on the floor opposite to him. "That's It!" he involuntarily exclaimed. . . . [Kitton 15]

G. K. Chesterton, critic and Dickensian, in 1907 pronounced the resulting illustration a psychological projection of Fagin's mental state.: "it does not look merely like a picture of Fagin; it looks like a picture by Fagin" (Charles Dickens, A Critical Study, p. 112; cited in Cohen, p. 23). Jane Rabb Cohen notes that, whereas Dickens became fixated on Bill Sikes and almost relished performing the murder of Nancy over and over again in his readings throughout England and the eastern United States, Cruikshank identified himself with Fagin, offering images of himself in George Cruikshank's Omnibus (May 1842) in which he has represented himself as possessing the face and skeletal physique of the cunning criminal.

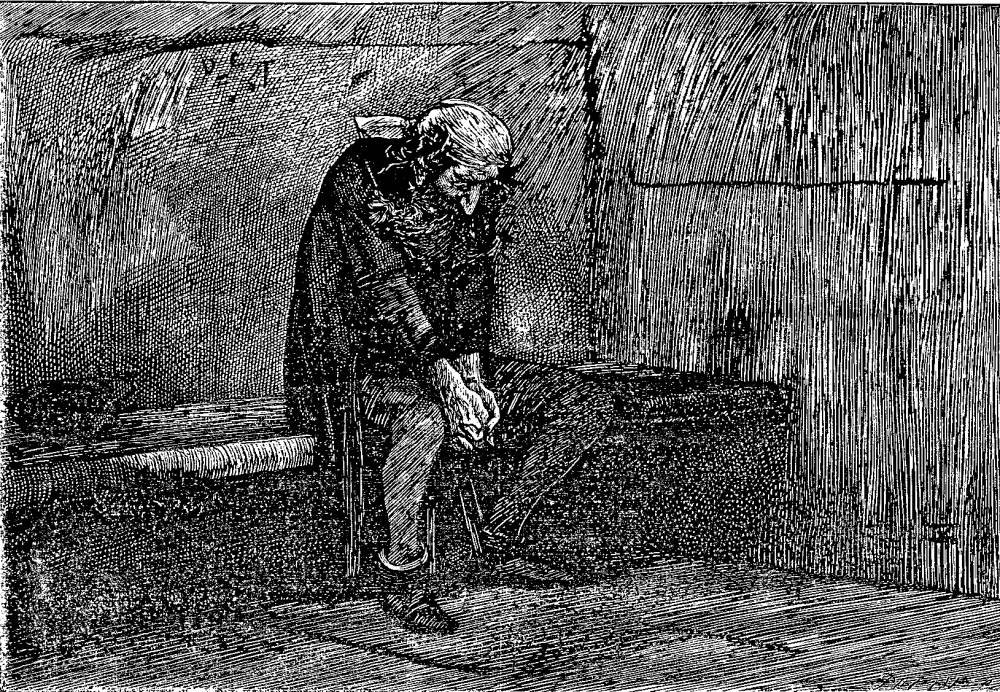

Although the 1870s Household Edition illustrator James Mahoney depicts Fagin in his last hours alive, his treatment of his subject clearly subsumes the slightly more caricatural treatment of Cruikshank. Having depicted Fagin with his open cash-box at the very beginning of his sequence of character studies, Sol Eytinge had no opportunity to revisit the character, and, perhaps as a consequence of Cruikshank's memorable plate, no inclination to attempt to outdo Dickens's original illustrator. In fact, Mahoney has realised an earlier passage when, having just received his death sentence, Fagin is searched before entering one of the condemned cells. Although manacled about the ankles like his counterpart in the 1839 engraving, Mahoney's figure rests upon a stone bench rather than a cot. Mahoney includes neither the bars or bible from the Cruikshank plate, and dispenses with the two embedded, hand-written notes (from the Sheriff, and therefore presumably directed towards inmates) notes above the prisoner. The only ornamentation in Mahoney's wood-engraving is the initials of several former occupants of the cell (upper left).

Again focussing on the figure of the condemned prisoner, Harry Furniss in his 1910 lithographic series depicts Fagin as manacled are wrists and ankles, staring vacantly ahead with eyes that glow in the darkness of the cell, whose bars are reflected on the floor. The shading of the figure and strong lines delineating his clothing and beard suggest a pent-up energy. As he stares at the reader, Fagin is an enigma, for neither remorse nor reflection is immediately apparent in his expression. He is an alienated figure, still dominating the page, but now bereft of associates and subordinates. His eyes shining "with a terrible light," Fagin in the Furniss illustration is both a haunted and a haunting presence, drawn with neither sentiment nor humour, but with smouldering intensity.

Thus, the preceding illustrators — Cruikshank, Mahoney, and finally Furniss — had provided Charles Pears with what amounted in 1912 to a living iconographic tradition of visual interpretation and reinterpretation of one of the most famous and harrowing scenes in Dickens, a tour de force for such a youthful writer. As an artist working in the caricatural style of Dickens's original illustrators Cruikshank and Phiz, Frederic W. Pailthorpe in 1885 perhaps felt that he should attempt such a revisiting of the scene so brilliantly realised by the initial illustrator. With simple pencil shading Pears achieves an understated tribute to Cruikshank that has the light from the barred window play upon the book of holy scripture — whether the Christian Bible or the Judaic Torah one cannot say with certainty, for there is no cross upon the cover, and Fagin is indeed visited by the local elders of his religion on Saturday evening —

Venerable men of his own persuasion had come to pray beside him, but he had driven them away with curses. They renewed their charitable efforts, and he beat them off. [306]

— and upon Fagin's face and knees, as if he is overlooking his one, best recourse: repentance. The strength of the light coming through the barred window may suggest that the time is Sunday morning, shortly before the visit by Oliver and Brownlow.

Pears reverses the position of the condemned and the wall opposite, showing him in a kind of apse, bareheade and without his hat on stone bed beside him. Indeed, Pears has reduced the scene to its essentials: the cell and the prisoner are simple blocks of light and shade with but three elements clearly delineated in the skilfully drawn pencil sketch: the bars, the book of scripture (its spine away from him), and the manacles on Fagin's ankles. Here is no caged animal or grisly demon — and no embedded texts or signs other than the book and the light of the coming day. Pears strips away the sentimentality and melodrama as he simply shows a bad man obsessed with the spectre of his own imminent death. Already the strong light of dawn breaking through the barred window is announcing the appointed hour of departure for the gallows is drawing nearer.

Left: George Cruikshank's depiction of Fagin in prison, detail from the wrapper (Chapman & Hall, 1846), bottom centre. Centre: George Cruikshank's Fagin in the condemned Cell (March 1839). Right: Harry Furniss's Charles Dickens Library Edition illustration Fagin in the Condemned Cell (1910). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Above: James Mahoney's 1871 engraving of Fagin awaiting his execution, He sat down on a stone bench opposite the door. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Clarke, J. Clayton. The Characters of Charles Dickens pourtrayed in a series of original watercolours by "Kyd.". London: Raphael Tuck,1890.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. "George Cruikshank." Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State U. P., 1980. Pp.15-38.

Darley, Felix Octavius Carr. Character Sketches from Dickens. Philadelphia: Porter and Coates, 1888.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. The Adventures of Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Bradbury and Evans; Chapman and Hall, 1846.

_______. The Letters of Charles Dickens. Ed. Madeline House and Graham Storey. The Pilgrim Edition. Oxford: Clarendon, 1965. Volume One (1820-29).

_______. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 55 vols. Illustrated by Felix Octavius Carr Darley and Sir John Gilbert. New York: Sheldon and Co., 1865.

_______. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Diamond Edition. 14 vols. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867. Vol. XI.

_______. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. Illustrated by James Mahoney. London: Chapman and Hall, 1871. Vol. I.

_______. The Adventures of Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Charles Dickens Library Edition. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. III.

_______. The Adventures of Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. The Waverley Edition. Illustrated by Charles Pears. London: Waverley, 1912.

Forster, John. "Oliver Twist 1838." The Life of Charles Dickens. Edited by B. W. Matz. The Memorial Edition. 2 vols. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1911. Vol. I, Book 2, Chapter 3.

Kitton, Frederic G. "George Cruikshank." Dickensand His Illustrators: Cruikshank, Seymour, Buss, "Phiz," Cattermole, Leech, Doyle, Stanfield, Maclise, Tenniel, Frank Stone, Topham, Marcus Stone, and Luke Fildes. 1899. Rpt. Honolulu: U. Press of the Pacific, 2004. Pp. 1-28.

Kyd. Characters of Charles Dickens. Nottingham: John Player & Sons, 1910.

Pailthorpe, Frederic W. (Illustrator). Charles Dickens's Oliver Twist. London: Robson & Kerslake, 1886. Set No. 118 (coloured) of 200 sets of proof impressions.

Created 18 March 2015 Last modified 8 May 2022