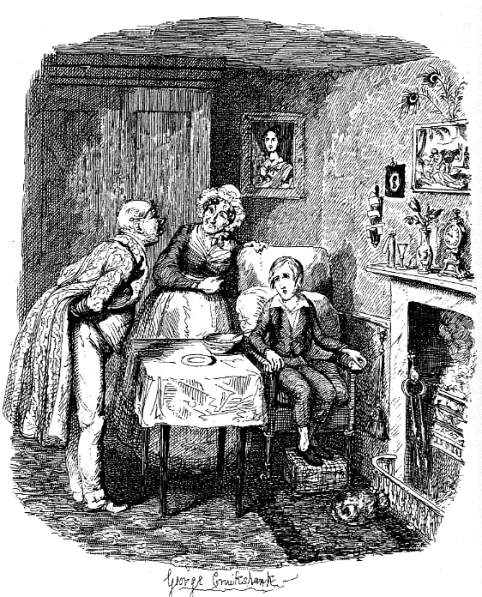

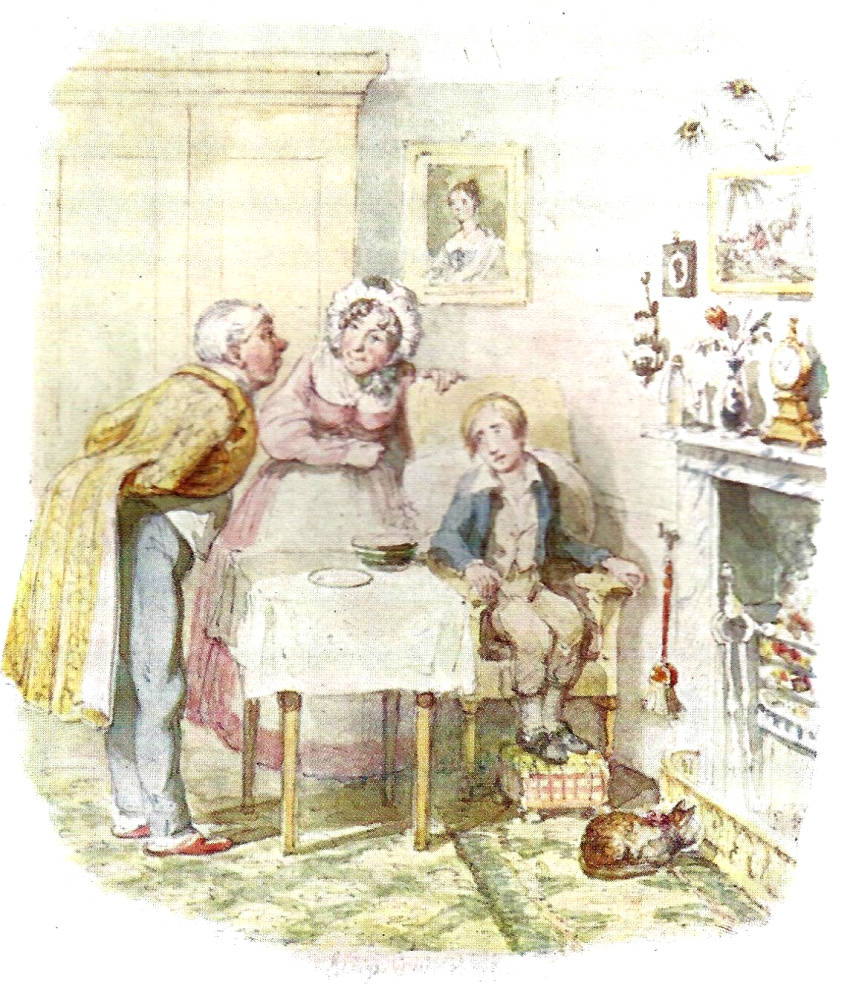

Oliver recovering from fever — the sixth steel engraving and later a watercolour for Charles Dickens's The Adventures of Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress, first published in volume by Richard Bentley after its August 1837 appearance in Bentley's Miscellany, Chapter XII. 4 ¼ by 3 ¾ inches (11 cm by 9.3 cm), vignetted, facing page 61 (originally leading off the monthly instalment). Cruikshank's own 1866 watercolour, commissioned by F. W. Cosens, is the basis for the 1911 chromolithograph. [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Passage Illustrated in the 1846 edition: Mr. Brownlow and Mrs. Bedwin pamper Oliver

It had been bright day, for hours, when Oliver opened his eyes; he felt cheerful and happy. The crisis of the disease was safely past. He belonged to the world again.

In three days' time he was able to sit in an easy-chair, well propped up with pillows; and, as he was still too weak to walk, Mrs. Bedwin had him carried down stairs into the little housekeeper's room, which belonged to her. Having him set, here, by the fireside, the good old lady sat herself down too; and, being in a state of considerable delight at seeing him so much better, forthwith began to cry most violently.

"Never mind me, my dear," said the old lady. "I'm only having a regular good cry. There; it's all over now; and I'm quite comfortable."

"You're very, very kind to me, ma'am," said Oliver.

"Well, never you mind that, my dear," said the old lady; "that's got nothing to do with your broth; and it's full time you had it; for the doctor says Mr. Brownlow may come in to see you this morning; and we must get up our best looks, because the better we look, the more he'll be pleased." And with this, the old lady applied herself to warming up, in a little saucepan, a basin full of broth: strong enough, Oliver thought, to furnish an ample dinner, when reduced to the regulation strength, for three hundred and fifty paupers, at the lowest computation.

"Are you fond of pictures, dear?" inquired the old lady, seeing that Oliver had fixed his eyes, most intently, on a portrait which hung against the wall; just opposite his chair.

"I don't quite know, ma'am, said Oliver, without taking his eyes from the canvas; "I have seen so few, that I hardly know. What a beautiful, mild face that lady's is!"

"Ah!" said the old lady, "painters always make ladies out prettier than they are, or they wouldn't get any custom, child. The man that invented the machine for taking likenesses might have known (r)that¯ would never succeed; it's a deal too honest. A deal," said the old lady, laughing very heartily at her own acuteness.

"Is — is that a likeness, ma'am?" said Oliver.

"Yes," said the old lady, looking up for a moment from the broth; "that's a portrait."

"Whose, ma'am?" asked Oliver.

"Why, really, my dear, I don't know," answered the old lady in a good-humoured manner. "It's not a likeness of anybody that you or I know, I expect. It seems to strike your fancy, dear."

"It is so very pretty," replied Oliver.

"Why, sure you're not afraid of it?" said the old lady: observing, in great surprise, the look of awe with which the child regarded the painting.

"Oh no, no," returned Oliver quickly; "but the eyes look so sorrowful; and where I sit, they seem fixed upon me. It makes my heart beat," added Oliver in a low voice, "as if it was alive, and wanted to speak to me, but couldn't."

"Lord save us!" exclaimed the old lady, starting; "don't talk in that way, child. You're weak and nervous after your illness. Let me wheel your chair round to the other side; and then you won't see it. There!" said the old lady, suiting the action to the word; "you don't see it now, at all events."

Oliver did see it in his mind's eye as distinctly as if he had not altered his position; but he thought it better not to worry the kind old lady; so he smiled gently when she looked at him; and Mrs. Bedwin, satisfied that he felt more comfortable, saited and broke bits of toasted bread into the broth, with all the bustle befitting so solemn a preparation. Oliver got through it with extraordinary expedition. He had scarcely swallowed the last spoonful, when there came a soft rap at the door. "Come in," said the old lady; and in walked Mr. Brownlow.

Now, the old gentleman came in as brisk as need be; but, he had no sooner raised his spectacles on his forehead, and thrust his hands behind the skirts of his dressing-gown to take a good long look at Oliver, than his countenance underwent a very great variety of odd contortions. Oliver looked very worn and shadowy from sickness, and made an ineffectual attempt to stand up, out of respect to his benefactor, which terminated in his sinking back into the chair again; and the fact is, if the truth must be told, that Mr. Brownlow's heart, being large enough for any six ordinary old gentlemen of humane disposition, forced a supply of tears into his eyes, by some hydraulic process which we are not sufficiently philosophical to be in a condition to explain.

"Poor boy, poor boy!" said Mr. Brownlow, clearing his throat. "I'm rather hoarse this morning, Mrs. Bedwin. I'm afraid I have caught cold." [Chapter XII, "In which Oliver is taken better care of than he ever was before. And in which the narrative reverts to the merry old gentleman and his youthful Friends," pp. 60-61 in the 1846 edition]

Commentary: Oliver in the Lap of Luxury

Dickens and Cruikshank now transport readers to a point several weeks after Oliver's release from detention and an imposed sentence of three months' hard labour; Oliver's incarceration had been miraculously forestalled by after the bookstall owner's testimony. Thus exonerated, Oliver, weak but finally recovered from the fever, now awakens in a different world. This is the upper-middle-class home of the affluent Mr. Brownlow's home in Pentonville, north London. Carried downstairs to the room of the kindly housekeeper, Mrs. Bedwin, Oliver pays special attention to a portrait of a young lady in her room.

Here is Victorian sentimentalism at its most effective deployment, as Dickens here introduces it obliquely, when the kindly Mr. Brownlow attempts to explain away rationally his tears of sympathy for the suffering child whose plight moved him to enact the role of the charitable traveller in "The Gospel According to St. Luke," 10:25-37. The telling detail in this picture is the biblical illustration above the mantelpiece (right). The subject, discernible even in so small a space, is the New Testament "Parable of the Good Samaritan." Although not mentioned by Dickens, the inset illustration serves as an analogue for the ministrations of the tender-hearted Mr. Brownlow and his kindly housekeeper, who has nursed Oliver back from the brink of death. Brownlow's conduct towards a total stranger, and, moreover, a person who is not member of his own class, must assure him eternal life, if Jesus in the parable is to be believed. However, instead of merely leaving the emaciated youth in charge of an innkeeper as in the parable, Brownlow brings the boy into his own home to recuperate.

Conspicuous on the wall immediately above and behind Oliver is yet another inset picture, a portrait that proves to be that of Oliver's mother, about whom in his delirium he has dreamed, as if she were his guardian angel. This scene with Oliver's charitable and even loving adults contrasts previous scenes involving child exploitation, including that of the "false" Samaritan, the master-thief Fagin; again, as in Oliver introduced to the respectable Old Gentleman, Cruikshank has positioned Oliver to the right and his saviours to the left, Mrs. Bedwin occupying the central position taken by the Artful Dodger in the earlier illustration.

All the other details in the little room bespeak comfort, tidiness, and good order, all features of the occupant, Mrs. Bedwin (a name suggestive, perhaps of "Bedouin," and therefore an oblique allusion to the Holy Land). The adults are framed by the large wardrobe (left rear), while Oliver is framed by his chairback and hassock; the effect is to draw the eye upward and to the right, to the portrait of a young lady. The detailing of the fireplace, including the bricabrac and the small cat, is pure Cruikshank.

The Good Samaritan, by the way, was something of a favourite subject with Victorian painters such as George Frederic Watts (1852) and John Everett Millais (1863). Indeed, the parable seems to have been a commonplace for philanthropic activity among the upper-middle and upper classes, as in the low relief sculpture for Sarah Elizabeth Wardroper by George Tinworth (1893-94).

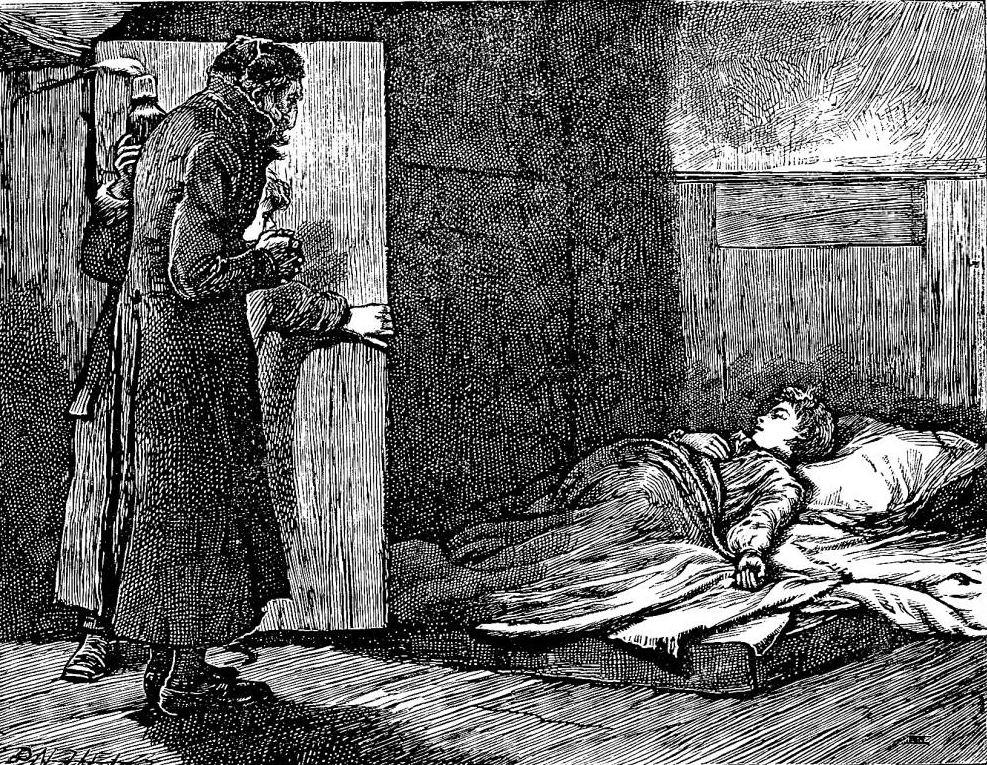

Relevant Illustrations from Other Editions (1871 and 1910)

Left: Mahoney's 1871 Household Edition engraving of the sleeping Oliver observed by Fagin and Monks, The boy was lying, fast asleep, on a rude bed upon the floor.. Right: Harry Furniss's Oliver and his Mother's Portrait (1910). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Related Material

- Oliver Twist as a Triple-Decker

- Oliver untainted by evil

- Like Martin Chuzzlewit, it agitates for social reform

- Oliver Twist Illustrated, 1837-1910

Scanned images and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. "George Cruikshank." Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State U. P., 1980. Pp. 15-38.

Darley, Felix Octavius Carr. Character Sketches from Dickens. Philadelphia: Porter and Coates, 1888.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. Oliver Twist. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Bradbury and Evans; Chapman and Hall, 1846.

_______. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 55 vols. Illustrated by F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. New York: Sheldon and Co., 1865.

_______. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Diamond Edition. 18 vols. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867. Vol. II.

_______. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 22 vols. Illustrated by James Mahoney. London: Chapman and Hall, 1871. Vol. II.

_______. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. III.

Forster, John. "Oliver Twist 1838." The Life of Charles Dickens. Ed. B. W. Matz. The Memorial Edition. 2 vols. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1911. Vol. 1, book 2, chapter 3. Pp. 91-99.

Grego, Joseph (intro) and George Cruikshank. "Oliver recovering from fever." Cruikshank's Water Colours. [27 Oliver Twist illustrations, including the wrapper and the 13-vignette title-page produced for F. W. Cosens; 20 plates for William Harrison Ainsworth's The Miser's Daughter: A Tale of the Year 1774; 20 plates plus the proofcover the work for W. H. Maxwell's History of the Irish Rebellion in 1798 and Emmetts Insurrection in 1803]. London: A. & C. Black, 1903. OT = pp. 1-106]. Page 24.

Kitton, Frederic G. "George Cruikshank." Dickens and His Illustrators: Cruikshank, Seymour, Buss, "Phiz," Cattermole, Leech, Doyle, Stanfield, Maclise, Tenniel, Frank Stone, Topham, Marcus Stone, and Luke Fildes. 1899. Rpt. Honolulu: U. Press of the Pacific, 2004. Pp. 1-28.

Created 20 April 2019 Last updated 10 January 2022