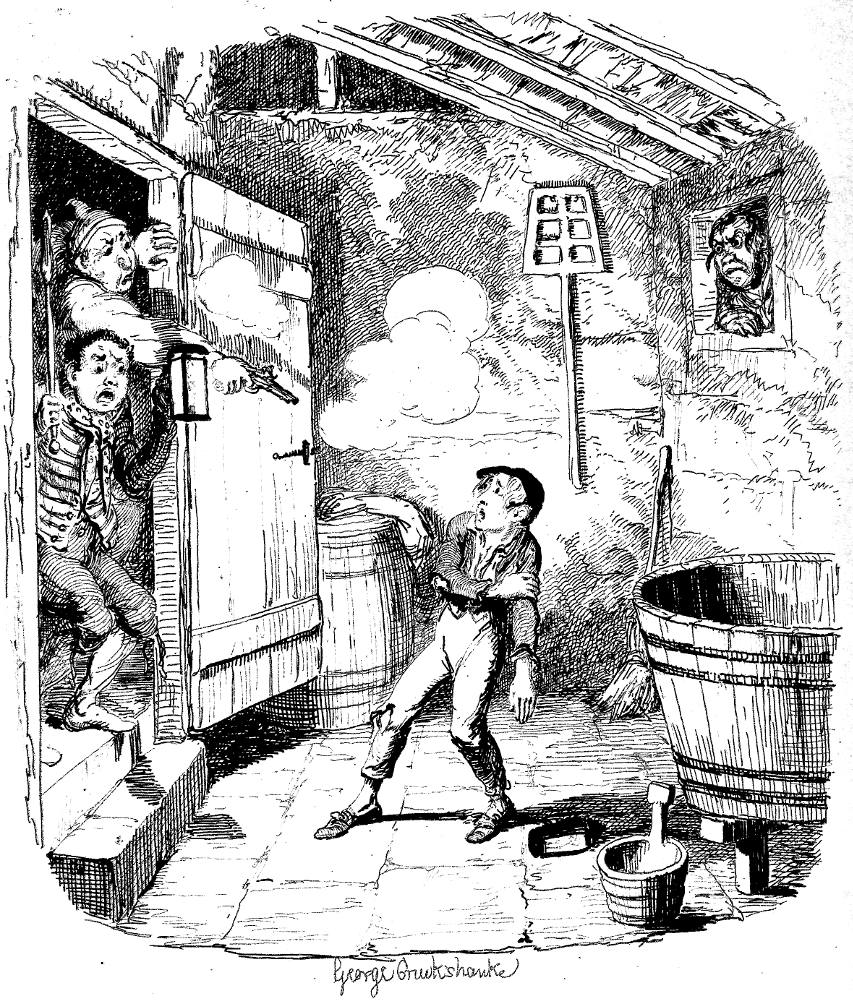

Master Bates explains a professional technicality — the ninth steel engraving and later a watercolour for Charles Dickens's The Adventures of Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress, first published in volume by Richard Bentley after its December 1837 appearance in Bentley's Miscellany, Chapter XVI (ninth instalment). 4 ¼ by 3 ¾ inches (10.6 cm by 9.5 cm), vignetted, facing page 100 in the 1846 edition (originally leading off the monthly number). Cruikshank's own 1866 watercolour, commissioned by book-collector F. W. Cosens, is the basis for the 1911 chromolithograph. [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Passage Illustrated: The Dangers of Being Scragged

Clayton J. Clarke ('Kyd") provided this Player's Cigarette Card study in 1910: The Artful Dodger Card No. 1.

"Look here!" said the Dodger, drawing forth a handful of shillings and halfpence. "Here's a jolly life! What's the odds where it comes from? Here, catch hold; there's plenty more where they were took from. You won't, won't you? Oh, you precious flat!"

"It's naughty, ain't it, Oliver?" inquired Charley Bates. " He'll come to be scragged, won't he?"

"I don't know what that means," replied Oliver.

"Something in this way, old feller," said Charley. As he said it, Master Bates caught up an end of his neckerchief; and, holding it erect in the air, dropped his head on his shoulder, and jerked a curious sound through his teeth; thereby indicating, by a lively pantomimic representation, that scragging and hanging were one and the same thing.

"That's what it means," said Charley. "Look how he stares, Jack!" [Chapter XVIII, "How Oliver passed his time in the improving society of his reputable friends," p. 100 in the 1846 edition]

Commentary: Dickens's Gallows Humour

Clayton J. Clarke ('Kyd"): Charley Bates.

The stoutly barred door in the Cruikshank plate reminds us of Fagin's previous isolation strategy, keeping Oliver away from the other boys in this sparsely furnished cell, and foreshadows Fagin's own destination at Newgate. Dickens seems to have been aware of the fact that "scragging" or "hanging" actually had little deterrent value for young career criminals such as the Artful Dodger. Using the logic of solitary confinement followed by socialization, Fagin attempts to persuade Oliver to join the gang of his own free will. Ironically, Charley's performance does seem to possess deterrent value for Oliver, despite Charley's and the Dodger's subsequent "glowing description of the numerous pleasures incidental to the life they led" (101). Determined to have his way, however, Fagin engages in "the game" every day with the boys, and regales Oliver with "droll and curious" stories about the robberies that he himself committed in youth. Part of his program of indoctrination is keeping Oliver constantly in the company of his chief acolytes.

"The Dodger" (otherwise, Jack Dawkins) and his extroverted companion, the exuberant ham-actor Charley Bates, know full well the inevitable consequences of their continuing to ply the "trade" of pickpocketing. But they console themselves with the dictum that, if they don't pick rich men's pockets, somebody else certainly will. In the other editions of the novel, the illustrators depict the Dodger and Charley as miniature adults, supremely self-confident and, in the wood-engravings of James Mahoney and the lithographs of Harry Furniss, dressed in adult clothing more than a little too large for them. While Dickens would have us take Sikes and Fagin seriously, as depraved criminals, he seems to regard the pair of street-wise Cockney pickpockets as vehicles for comic relief — certainly, Cruikshank's rendition of them in this scene is highly entertaining. They smoke, drink, swagger, and speak thieves' cant like regular adult criminals, but nevertheless engage the reader with their verbal wit and camaraderie, and thereby excuse themselves from the fate that awaits Bill Sikes and Fagin. John Forster in his The Life of Charles Dickens defended the presence of such criminal scenes in the story as performing a service to society, citing other "Newgate" or underworld crime stories, including Alain-René Lesage's Gil Blas, John Gay's The Beggar's Opera, and Henry Fielding's Jonathan Wild — to which he might have added William Harrison Ainsworth's Jack Sheppard. We can rub shoulders with vice and crime in a literary text, argues Forster, "but our morals stand none the looser for any of them" (Vol. 1, p. 96). Although nowhere in the novel does Dickens justify or make vice attractive, he seldom exploits it for the sake of generating suspense, as Ainsworth does; Forster maintains that Dickens's intention is always moral:

Crime is not more intensely odious, all though, than it is also most unhappy. Not merely when its exposure comes, when latent recesses are laid bare, and the agonies of remorse are witnessed; not in the great scenes only, but in lighter and apparently careless passages; this is emphatically so. [Vol. 1, p. 96]

Although Great Britain ceased to use capital punishment as a deterrent to crime in 1965, the last public hanging occurred much earlier, in 1868. Despite the great depression of the Hungry Forties, far fewer people were hanged in the 19th century than the 18th: whereas some six thousand swung at the end of a rope from 1735 to 1799, only 3,365 were hanged publically in the period of 1800-1899 — despite the fact that transportation, which had become uncommon several years earlier, was finally abolished in 1868. The Capital Punishment Amendment Act of 1868 abolished public hanging, which Dickens held incited brutality and excited sadistic impulses in the populace; he found such exhibitions sickening, and inveighed against the practice. Hanging itself was not abolished; it merely took place behind the walls of county prisons — with his telescope Thomas Hardy as a boy witnessed such a hanging at Dorchester Gaol.

Ironically, during the period in which Dickens set his Newgate Novel, criminals were hanged for offences other than murder: in 1820, moreover, nobody was hanged for homicide, but 29 were hanged at Newgate for such lesser crimes as uttering forged notes (twelve instances) and for theft (twelve for robbery or burglary, and five for highway robbery). Charley Bates was quite right, then, about the fate that would probably attend his following the "trade." Ironically, too, were he to be tried and found guilty of anything other than theft, rape, murder, arson, or forgery, he would most certainly be transported and not hanged until well into the century. Typically in the eighteenth century, crimes against property merited hanging: there were roughly two hundred such crimes, that number only being reduced to just over one hundred in 1823 by the Tory administration of Sir Robert Peel. If the period of the main action of the novel is "Post-Reform Bill," so to speak, Charley's chances of escaping the noose would increase, as, seven years after Sir Robert Peel's initiative, the Liberal administration of Lord John Russell abolished the death sentence for horse stealing and housebreaking. One must assume that, if the story occurs in the early 1830s, Bill Sikes would have hanged as a murderer rather than a mere burglar, but Fagin's hanging for his crimes against property, although on a massive scale, would be less likely.

On 23 February 1846, Charles Dickens published a lengthy editorial for The Daily News against capital punishment; his chief argument was that failures in the judicial system occasionally resulted in the execution of a person innocent of the crime with which he had been charged.

After the murder of Nancy and the deaths of Sikes and Fagin, Charley Bates reforms himself, "appalled by Sikes's crime" (310), and, settling upon an agricultural life far removed from the Great Oven, eventually becomes "the merriest young grazier in all Northamptonshire" (310). His companion in crime, the indefatigible Jack Dawkins, is tried for numerous petty thefts, specifically for stealing a silver snuff-box, and in Chapter 43 is sentenced to transportation, despite a vociferous and witty Cockney defense in which he tries to put the court itself on trial.

Relevant Illustrations from the serial and later editions (1837-1910)

Left: George Cruikshank's The Burglary. Centre: Sol Eytinge, Junior's The Artful Dodger and Charley Bates (1867). Right: Harry Furniss's "Oliver falls in with the Artful Dodger" (1910).[Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Left: Harry Furniss's "The Dodger's Toilet" (1910). Right: Mahoney's Household Edition illustration (1871) "Hello, my covey! What's the row?". [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Related Material

- Nancy and Bill Sikes in various editions of Oliver Twist (1837-1910)

- Oliver Twist Illustrated, 1837-1910

- Early dramatic adaptations of Oliver Twist (1838-1842)

- Alternative Dickens: cartoon based on Cruikshank in Oliver Twist

Scanned images and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. "George Cruikshank." Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State U. P., 1980. Pp. 15-38.

Darley, Felix Octavius Carr. Character Sketches from Dickens. Philadelphia: Porter and Coates, 1888.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. The Adventures of Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Bradbury and Evans; Chapman and Hall, 1846.

_______. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 55 vols. Illustrated by F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. New York: Sheldon and Co., 1865.

_______. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Diamond Edition. 14 vols. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

_______. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 22 vols. Illustrated by James Mahoney. London: Chapman and Hall, 1871. Vol. I.

_______. The Adventures of Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. 3.

Forster, John. "Oliver Twist 1838." The Life of Charles Dickens. Ed. B. W. Matz. The Memorial Edition. 2 vols. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1911. Vol. 1, book 2, chapter 3. Pp. 91-99.

Grego, Joseph (intro). Cruikshank's Water Colours. [27 Oliver Twist illustrations, including the wrapper and the 13-vignette title-page produced for F. W. Cosens; 20 plates for William Harrison Ainsworth's The Miser's Daughter: A Tale of the Year 1774; 20 plates plus the proofcover the work for W. H. Maxwell's History of the Irish Rebellion in 1798 and Emmetts Insurrection in 1803]. London: A & C Black, 1903. OT = pp. 1-106]. Book in the Rare Book Collection of the University of Toronto.

Kitton, Frederic G. "George Cruikshank." Dickens and His Illustrators: Cruikshank, Seymour, Buss, "Phiz," Cattermole, Leech, Doyle, Stanfield, Maclise, Tenniel, Frank Stone, Topham, Marcus Stone, and Luke Fildes. 1899. Rpt. Honolulu: U. Press of the Pacific, 2004. Pp. 1-28.

Pailthorpe, Frederic W. (Illustrator). Charles Dickens's Oliver Twist. London: Robson & Kerslake, 1886. Set No. 118 (coloured) of 200 sets of proof impressions.

Patten, Robert L. George Cruikshank's Life, Times, and Art, Volume Two: 1836-1878. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1996.

Patten, Robert L. George Cruikshank: A Revaluation. Princeton: Princeton U. P., 1992.

Created 3 October 2014 Last modified 23 December 2021