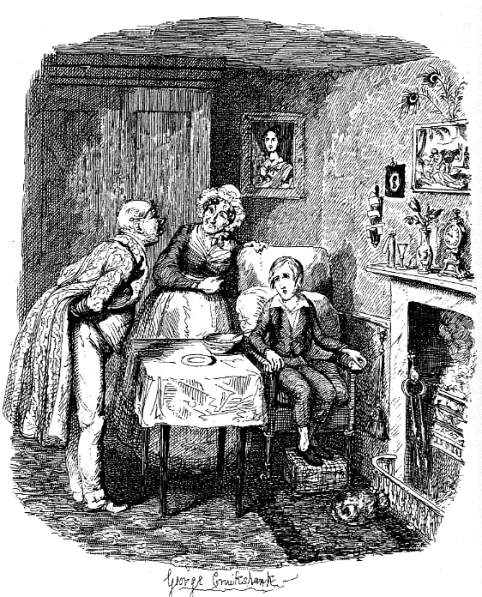

Waiting for Oliver by Harry Furniss in Dickens's The Adventures of Oliver Twist, Charles Dickens Library Edition, facing III, 97 (based on 106). The illustration itself is positioned earlier in Chapter 14, but occurs some seven pages after the textual passage it realizes, producing a proleptic reading of the illustration; lithograph, 9.0cm by 13.6 cm, vignetted.

Passage Illustrated

"Let me see: He'll be back in twenty minutes, at the longest," said Mr. Brownlow, pulling out his watch, and placing it on the table. "It will be dark by that time."

"Oh! you really expect him to come back, do you?" inquired Mr. Grimwig.

"Don't you?" asked Mr. Brownlow, smiling.

The spirit of contradiction was strong in Mr. Grimwig's breast, at the moment; and it was rendered stronger by his friend's confident smile.

"No," he said, smiting the table with his fist, "I do not. The boy has a new suit of clothes on his back, a set of valuable books under his arm, and a five-pound note in his pocket. He'll join his old friends the thieves, and laugh at you. If ever that boy returns to this house, sir, I'll eat my head."

With these words he drew his chair closer to the table; and there the two friends sat, in silent expectation, with the watch between them. [Chapter 14, "Comprising further particulars of Oliver's stay at Mr. Brownlow's, with the remarkable prediction which one Mr. Grimwig uttered concerning him, when he went out on an errand," 104]

The Charles Dickens Library Edition’s Long Caption

"If ever that boy returns to this house, sir, I'll eat my head." said Mr. Grimwig. With these words he drew his chair closer to the table; and there the two friends sat, in silent expectation, with the watch between them. [106]

Commentary: Furniss’s Emphasis upon Grimwig

Although Dickenshimself selected for illustration by the house artist of Bentley's Miscellany the subsequent scene in which Charley Bates explains a "professional technicality" (hanging) for Oliver early in the December 1837 serial instalment, there is no surviving correspondence regarding the novelist's instructions about the initial appearance of either the kindly Mr. Brownlow or his sardonic opposite, Mr. Grimwig. Furniss elevates the status of Brownlow's cynical friend by depicting him at this critical junction in the story. Indeed, Furniss shows Grimwig's expression, and distinguishes him from Brownlow by his full head of hair, rather old-fashioned clothing (he wears breeches, whereas Browlow wears trosers), and greater physical bulk.

The Bunyanesquely-named character whose studied misanthropy is only superficial (put on, like a wig) and hides a kind heart, Mr. Grimwig counters his friend's optimistic appraisal of Oliver with world-weary pessimism. In the present picture, Furniss renders the two wealthy, middle-aged bourgeoisie,seen in earlier editions such as the Diamond Edition (1867) wood-engraving Mr. Brownlow and Mr. Grimwig (see below), as rather different physical types. In the 1837-38 serial edition in Bentley's Miscellany, Dickens's original illustrator George Cruikshank does not represent Mr. Grimwig at all, but does depict Mr. Brownlow in a series of illustrations, notably Oliver recovering from fever (Part Seven, September 1837). In this early illustration, Cruikshank presents Mr. Brownlow as an antitype to Fagin — an authentic rather than an ersatz Good Samaritan, wearing a clean dressing-gown, and facilitating the boy's recovering from a fever.

The Furniss illustration emphasis the different attitudes that the friends bring towards the putative return of the boy that the humanitarian Brownlow has brought into his own home to nurse back to health. Grimwig is certain that the boy will revert to his criminal associates (with the books and the five-pound note), and Brownlow certain that the boy will return shortly from returning the books to the book-seller at The Green. The cynical Grimwig, at heart a decent man who does not want to see his friend disappointed, revises his opinion of Oliver later in the story. Although many illustrators of the novel offer several interpretations of the philanthropic Brownlow, the only other artist to do justice to Grimwig as a student of human nature is Harry Furniss in his rather more animated treatment of this scene in Waiting for Oliver, in which the pair are studying Brownlow's gold pocket-watch open on the table between them (and therefore the focal point of the illustration) and awaiting the end of the predicted twenty minutes. Eytinge's illustration conveys are a far subtler sense of the elderly bachelors with contrasting natures — and includes both the pocket-watch and the portrait of Oliver's mother (strategically placed, upper centre). Mahoney's study of the pair fails to distinguish one friend from the other in the scene in chapter seventeen in which the avaricious Bumble turns up at Brownlow's home in Pentonville in response to the advertisement in theLondon newspaper offering five guineas for information that will "tend to throw any light upon [Oliver's] previous history" (Illustrated Library Edition, 126).

Furniss permits us to study Grimwig's bluff, slightly smiling visage ("I told you so," the smile implies), but leaves Brownlow's undoubtedly more concerned facial expression a matter for the sympathetic reader to construct. He effectively differentiates the two old friends by their hairstyles and fashions, for Grimwig wears breaches but has a full head of hair (Brownlow, in contrast, is balding, bespectacled, and dressed in Regency stovepipe trousers and tailcoat). Ridiculing the notion that the child will remain faithful, Grimwig leans back slightly, quite certain that he is correct about Oliver's thanklessness; however, the apprehensive Brownlow leans forward to study the movement of the minute-hand assiduously. The picture creates suspense as to whether Oliver will return, and the text does nothing to alleviate that suspense. Rather, cliff-hanging chapter ending and illustration combine to heighten suspense and propel reader forward into the next chapter, which was originally the second of two in instalment no. 7. At the end of the September 1837 number the pair are still sitting "perseveringly, in the dark parlour: with the watch between them" (111). Thus, the watch and the passage of time and the exhaustion of trust that it implies, is foregrounded in the reader's consciousness by the illustration, which applies the conclusions of both Chapters 14 and 15 — in the original serial leading to a genuine curtain as the reader wonders what steps Brownlow will take to retrieve the lost prodigal and redeem his faith in the boy upon whom he has bestowed his charity and affection.

Illustrations from the Serial (1837), the Diamond Edition (1867), the Household Edition (1871)

Left: Cruikshank's original version of Oliver recovering from the fever. Right: Sol Eytinge, Junior's Diamond Edition wood-engraving of the old friends awaiting Oliver's return in Mr. Brownlow and Mr. Grimwig (1867).

Above: Mahoney's Household Edition illustration of Bumble's visit to Mr. Brownlow's Pentonville residence to claim the reward for information about Oliver in "A Beadle! A parish beadle, or I'll eat my head" (1871).

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.].

Bibliography

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. The Adventures of Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Bradbury and Evans; Chapman and Hall, 1838; rpt. with revisions 1846.

_____. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 55 vols. Illustrated by F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. New York: Sheldon and Co., 1865.

_____. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Diamond Edition. 14 vols. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

_____. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 22 vols. Illustrated by James Mahoney. London: Chapman and Hall, 1871. Vol. I.

_____. The Adventures of Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. III.

_____. The Adventures of Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. The Waverley Edition. Illustrated by Charles Pears. London: Waverley, 1912.

_____.The Letters of Charles Dickens. Ed. Graham Storey, Kathleen Tillotson, and Angus Eassone. The Pilgrim Edition. Oxford: Clarendon, 1965. Vol. I (1820-1839).

Forster, John. "Oliver Twist 1838." The Life of Charles Dickens. Ed. B. W. Matz. The Memorial Edition. 2 vols. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1911. Vol. I, Book 2, Chapter 3.

Vann, J. Don. "Oliver Twist." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: The Modern Language Association, 1985, 62-63.

Created 27 January 2015

Last modified 14 February 2020