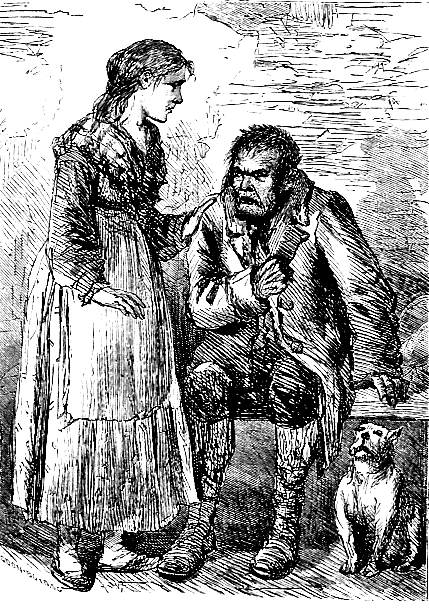

"Then, stooping softly over the bed, she kissed the robber's lips." — James Mahoney's illustration in Chapter 39 that prepares readers of the Household Edition for Nancy's journey to see Rose Maylie at a West End hotel near Hyde Park; this cross-town adventure will in turn lead to Nancy's revealing Fagin's compact with Monks to Mr. Brownlow and Rose Maylie, and consequently to Nancy's murder. In the original narrative-pictorial serial sequence by George Cruikshank in Bentley's Miscellany, the periodical reader encountered instead two Nancy-related illustrations leading to the same inevitable conclusion of Nancy's tale: Mr. Fagin and his pupil recovering Nancy, for Chapter 39 (Part 17, August 1838); and a pictorial realisation of Fagin's securing "Morris Bolter" (otherwise, Noah Claypole) to shadow Nancy's movements in The Jew & Morris Both begin to understand each other, for Chapter 42of The Adventures of Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress in Part 19 (November 1838). The Mahoney illustration of Nancy's kissing the drugged Sikes prior to approaching Rose with her information about Monks occurs on page 145, several pages before the textual passage realised. 1871. Wood engraving by the Dalziels, 10.8 cm high by 13.7 cm wide.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite it in a print one.]

Passage Realised

Fortifying himself with this assurance, Sikes drained the glass to the bottom, and then, with many grumbling oaths, called for his physic. The girl jumped up, with great alacrity; poured it quickly out, but with her back towards him; and held the vessel to his lips, while he drank off the contents.

"Now,"said the robber, "come and sit aside of me, and put on your own face; or I'll alter it so, that you won't know it agin when you do want it."

The girl obeyed. Sikes, locking her hand in his, fell back upon the pillow: turning his eyes upon her face. They closed; opened again; closed once more; again opened. He shifted his position restlessly; and, after dozing again, and again, for two or three minutes, and as often springing up with a look of terror, and gazing vacantly about him, was suddenly stricken, as it were, while in the very attitude of rising, into a deep and heavy sleep. The grasp of his hand relaxed; the upraised arm fell languidly by his side; and he lay like one in a profound trance.

"The laudanum has taken effect at last,"murmured the girl, as she rose from the bedside. "I may be too late, even now."

She hastily dressed herself in her bonnet and shawl: looking fearfully round, from time to time, as if, despite the sleeping draught, she expected every moment to feel the pressure of Sikes's heavy hand upon her shoulder; then, stooping softly over the bed, she kissed the robber's lips; and then opening and closing the room-door with noiseless touch, hurried from the house.

A watchman was crying half-past nine, down a dark passage through which she had to pass, in gaining the main thoroughfare.

"Has it long gone the half-hour?" asked the girl.

[Chapter 39, "Introduces Some Respectable Characters with whom the Reader is Already Acquainted, and Shows How Monks and the Jew Laid Their Worthy Heads Together," p. 147]

Commentary

Although Cruikshank and Furniss focus on Nancy's supposed "hysterics" as the gang attempts to cure her of them, the other illustrators have dealt instead with the deplorable physical and mental state into which Sikes and his common-law wife have fallen since the botched robbery in Chertsey. Mahoney has developed a rare scene of tenderness involving Sikes, delirious from unwittingly consuming laudanum, and the ministering Nancy, who is about to slip out to contact Rose Maylie in order to reveal what she knows of the plot instigated by Monks against Oliver, the knowledge she has gleaned from overhearing a recent conference between Monks and Fagin when she went to pick up expense money for Sikes.

Again, Mahoney describes a tranquil surface that the reader, having acquired additional knowledge of the principals from the accompanying text, must react against. Indeed, Nancy's tender regard for Sikes, despite his roughness, is genuine; however, the text reveals that she has just administered to him a powerful sedative so that, undetected and unobserved, she can make the lengthy trip to the West End and reveal the plot against Oliver to Rose Maylie, of whose identity and involvement in the boy's fortunes she has also learned from overhearing Monks's conversation with Fagin. The illustration draws the reader's attention to Nancy's conflicted relationship with the burglar, whom she loves but fears. Mahoney reduces both characters to signifying postures, for Sikes is an inert bulk on the bed, and Nancy a ministering nurse — significantly, Mahoney prevents the reader from studying her facial expression, that that one must conjecture about what conflicting emotions would be present as she determines to defend Oliver from the machinations of "Monks." The light in the Mahoney illustrations falls most strongly on the face and upper body of Sikes — and on the bottle and glass from which he has just drunk.

Illustrations from the original serial edition (1838), Diamond Edition (1867), and Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910)

Left: Sol Eytinge, Junior's "Bill Sikes and Nancy". Center: George Cruikshank's "Mr. Fagin and his pupils recovering Nancy". Right: Harry Furniss's Charles Dickens Library Edition illustration (1910) "Nancy in Hysterics". [Click on images to enlarge them.]

References

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. "George Cruikshank." Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State U. P., 1980. Pp. 15-38.

Darley, Felix Octavius Carr. Character Sketches from Dickens. Philadelphia: Porter and Coates, 1888.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. The Letters of Charles Dickens. Ed. Graham Storey, Kathleen Tillotson, and Angus Eassone. The Pilgrim Edition. Oxford: Clarendon, 1965. Vol. 1 (1820-1839).

Dickens, Charles. Oliver Twist. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Bradbury and Evans; Chapman and Hall, 1846.

Dickens, Charles. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 55 vols. Il. F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. New York: Sheldon and Co., 1865.

Dickens, Charles. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Diamond Edition. 18 vols. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

Dickens, Charles. The Adventures of Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. Illustrated by James Mahoney. London: Chapman and Hall, 1871.

Dickens, Charles. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Charles Dickens Library Edition. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. London: Educational Book Company, 1910.

Last modified 17 December 2014