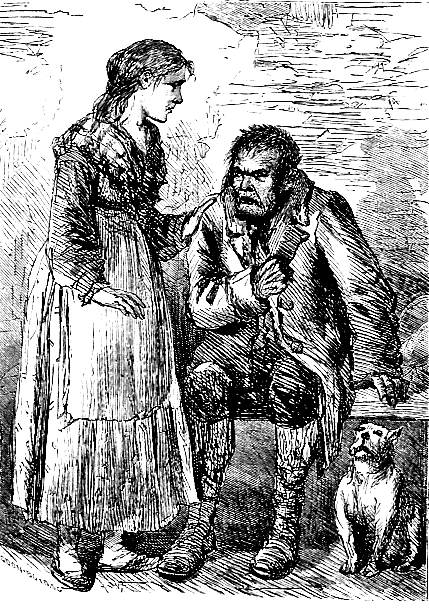

"When it became quite dark, and they returned home, the young lady would sit down to the piano, and play some pleasant air" — James Mahoney's seventeenth illustration emphasizes the sudden change in Oliver's life, the delicious Wordsworthian purity of life close to nature that Oliver, now an upper-middle class child, experiences over the next three months with the Maylies in an English village. Whereas Cruikshank in the original serial had focussed on more dramatic and humorous incidents, Mahoney again tends to favour a sentimental moment for realisation in the Household Edition. In the original narrative-pictorial serial sequence by George Cruikshank in Bentley's Miscellany, the periodical reader encountered a pictorial realization of the aptly named detectives Blathers and Duff as they question Oliver, who is still recovering from fever in Oliver waited on by the Bow Street Runners in Part 14, May 1838. Telegraphing the fact that Oliver will not at this point reconnect with Mr. Brownlow but will remain with the Maylies, Mahoney's idyllic twilight scene, situated textually in the midst of Oliver's interrogation by the police officers in Chapter 31 rather than in Chapter 32, is on page 113. 1871. Wood engraving by the Dalziels, 10.7 cm high by 13.8 cm wide.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite it in a print one.]

Passage Realised

Sending the plate, which had so excited Fagin's cupidity, to the banker's; and leaving Giles and another servant in care of the house, they departed to a cottage at some distance in the country, and took Oliver with them.

Who can describe the pleasure and delight, the peace of mind and soft tranquility, the sickly boy felt in the balmy air, and among the green hills and rich woods, of an inland village! . . . .

It was a happy time. The days were peaceful and serene; the nights brought with them neither fear nor care; no languishing in a wretched prison, or associating with wretched men; nothing but pleasant and happy thoughts. Every morning he went to a white-headed old gentleman, who lived near the little church: who taught him to read better, and to write: and who spoke so kindly, and took such pains, that Oliver could never try enough to please him. Then, he would walk with Mrs. Maylie and Rose, and hear them talk of books; or perhaps sit near them, in some shady place, and listen whilst the young lady read: which he could have done, until it grew too dark to see the letters. Then, he had his own lesson for the next day to prepare; and at this, he would work hard, in a little room which looked into the garden, till evening came slowly on, when the ladies would walk out again, and he with them: listening with such pleasure to all they said: and so happy if they wanted a flower that he could climb to reach, or had forgotten anything he could run to fetch: that he could never be quick enough about it. When it became quite dark, and they returned home, the young lady would sit down to the piano, and play some pleasant air, or sing, in a low and gentle voice, some old song which it pleased her aunt to hear. There would be no candles lighted at such times as these; and Oliver would sit by one of the windows, listening to the sweet music, in a perfect rapture. [117-18]

Commentary

Having dragged himself to the Maylies' front door after being dumped in a ditch by the fleeing Sikes, Oliver, near death, providentially encounters his mother's sister. Although George Cruikshank took obvious delight in depicting Oliver's reception by the Maylies' suspicious servants in Oliver at Mrs. Maylie's door (Part 13, April 1838), and the interrogation of the sickly child in Oliver waited on by the Bow Street Runners (Part 14, May 1838), for Chapter 31 Mahoney both attempted and achieved less in a scene that depicts neither the Maylies nor Dr. Losberne nor Oliver himself; indeed, it is as if Mahoney expected that readers would already be familiar with Cruikshank's steel engravings, and therefore avoided duplicating those earlier, highly successful realisations, both of which continue Oliver's "progress" out of the underworld and back into his proper station in English society. Indeed, Dickens establishes the pattern of Oliver's being apprehended as a thief and then exonerated and released into the custody of kindly, affluent people associated with his parents (for Mr. Brownlow from north of London was his father, Edwin Leeford's best friend; and Rose, Oliver's aunt, was adopted by the Maylies in Surrey).

However, the new element is the inexplicable disappearance of Mr. Brownlow, for, when Dr. Losberne drives in Oliver in his carriage to Pentonville, they discover that the house is "to let," and that the owner has moved his entire household to the West Indies. For the next three months, Oliver experiences what it is to be an upper-middle-class child far removed from the vice and crime of the metropolis. Whereas in the Mahoney sequence, there is no jarring element, in the Cruikshank sequence the master criminal appears in the very garden outside Oliver's window, accompanied by a strange. malevolent gentleman, who observe the boy as he dozes over his books in Monks and the Jew (Part 15, June 1838), for Chapter 34 of The Adventures of Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress. In the Mahoney idyll, there is no snake to marr the edenic scene, just an elderly lady dozing on a sofa as she listens to her niece play the piano in the darkening parlour after sunset. Oliver, neareast the garden window, sits listening intently rather than merely drinking in the comfortable situation.

What distinguishes Mahoney's work from that of Dickens's earlier illustrators — notably George Cruikshank and Hablot Knight Browne — is that he is consciously complementing rather than extending the narrative of the author, attending to matters of ambience, tone, and mood rather than action or even characterisation. The musical interlude is pertinent to this notion since Mahoney's image establishes a suitable feeling to accompany the Romantic idyll, like music to lyrics, that is, the Dickens letterpress or text. The effect, then, of reading the Household Edition volume is rather different from reading the original serial, whose illustrations establish an anticipatory set in the reader's mind and comment upon the text, or the 1846 Chapman and Hall volume, whose strategically placed illustrations invite the reader to peruse certain key moments in the plot attentively, comparing image and text. Mahoney does not attend much to the details of the scene; rather, he establishes a suitable mood or tone derived from a sensitive reading of a less plot-oriented moment.

Subsequent illustrators have enjoyed to varying degrees the opportunity for depicting the sensational and melodramatic events in the "Chertsey" chapters, but have neglected the more tranquil aspects of Oliver's sojourn with the Maylies. Sol Eytinge, Junior, in his dual portrait of the dissolute Bill Sikes and Nancy for Chapter 39, keeps his eye on the more sensational characters and aspects of the crime-and-detection plot, here showing the physical and moral consequences of the criminal couple's involving the blameless child in t heir burglary scheme. In the 1910 Charles Dickens Library Edition volume, Harry Furniss carefully graphs the events leading up to Oliver's integration into the Maylie household, from his being fired upon by the servants and left in a ditch to die to his being watched over in his sleep by Rose Maylie and Dr. Losberne in Chapter 30 as he recovers from the ordeal of The Burglary in Chapter 21.

Relevant Illustrations from the serial edition (1837-39) and the Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910)

Left: George Cruikshank's Monks and the Jew (1838). Centre: Sol Eytinge, Junior's Bill Sikes and Nancy (1867). Right: Harry Furniss's The wounded Oliver smiles in his Sleep (1910). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

References

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. "George Cruikshank." Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State U. P., 1980. Pp. 15-38.

Darley, Felix Octavius Carr. Character Sketches from Dickens. Philadelphia: Porter and Coates, 1888.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. Oliver Twist. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Bradbury and Evans; Chapman and Hall, 1846.

Dickens, Charles. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 55 vols. Il. F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. New York: Sheldon and Co., 1865.

Dickens, Charles. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Diamond Edition. 18 vols. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

Dickens, Charles. The Adventures of Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. Illustrated by James Mahoney. London: Chapman and Hall, 1871.

Dickens, Charles. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Charles Dickens Library Edition. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. London: Educational Book Company, 1910.

Last modified 11 December 2014