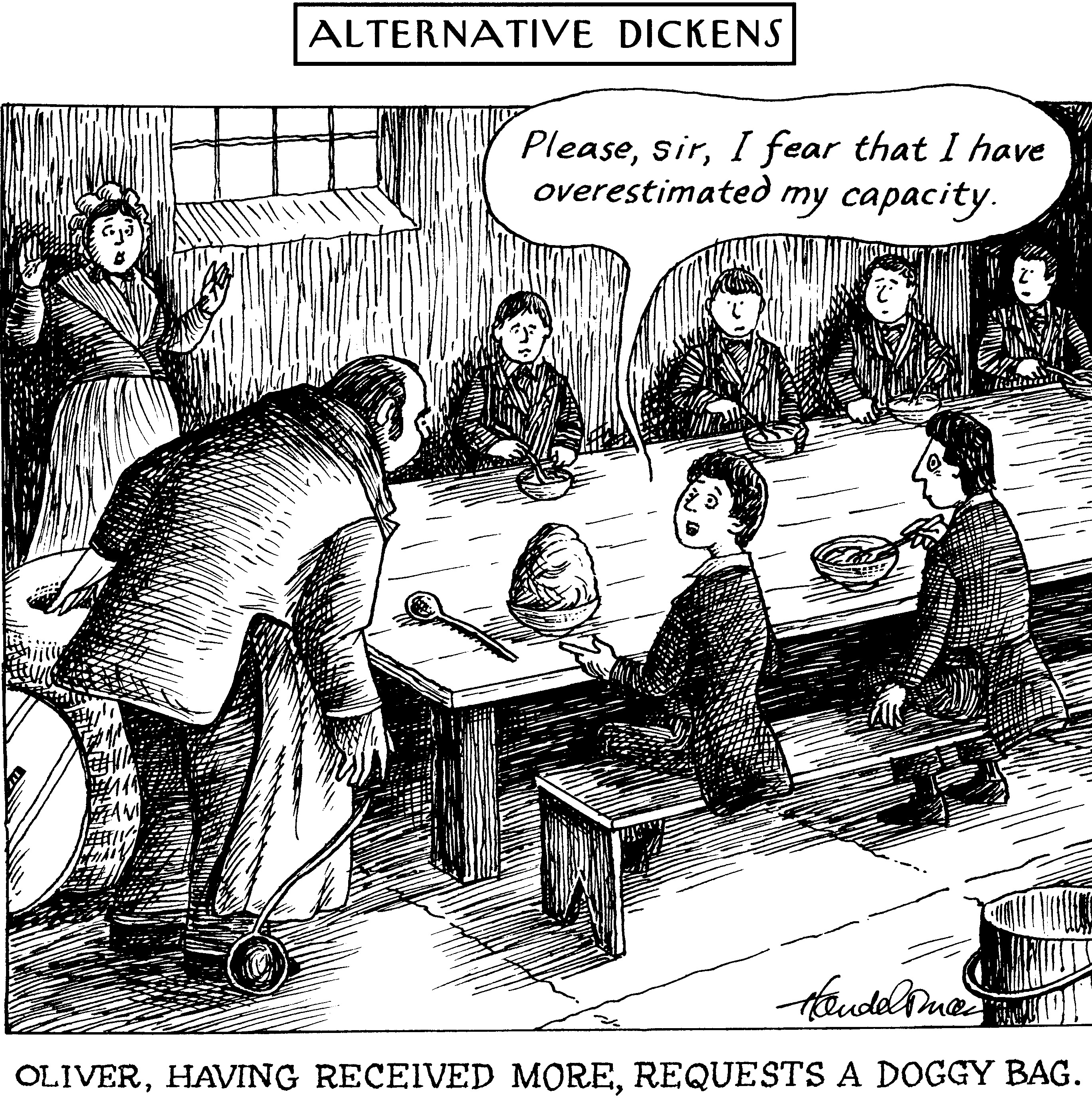

Alternative Dickens. Oliver, having received more, requests a doggy bag. J. B. Handelsman (1922-2007). The cartoon, which first appeared in the 2 December 1992 issue of The New Yorker is used courtesy of Condé-Nast Image Licensing and may not be used without their written permission.

“Alternative Dickens” — Handelsman Parodies Classic Dickens

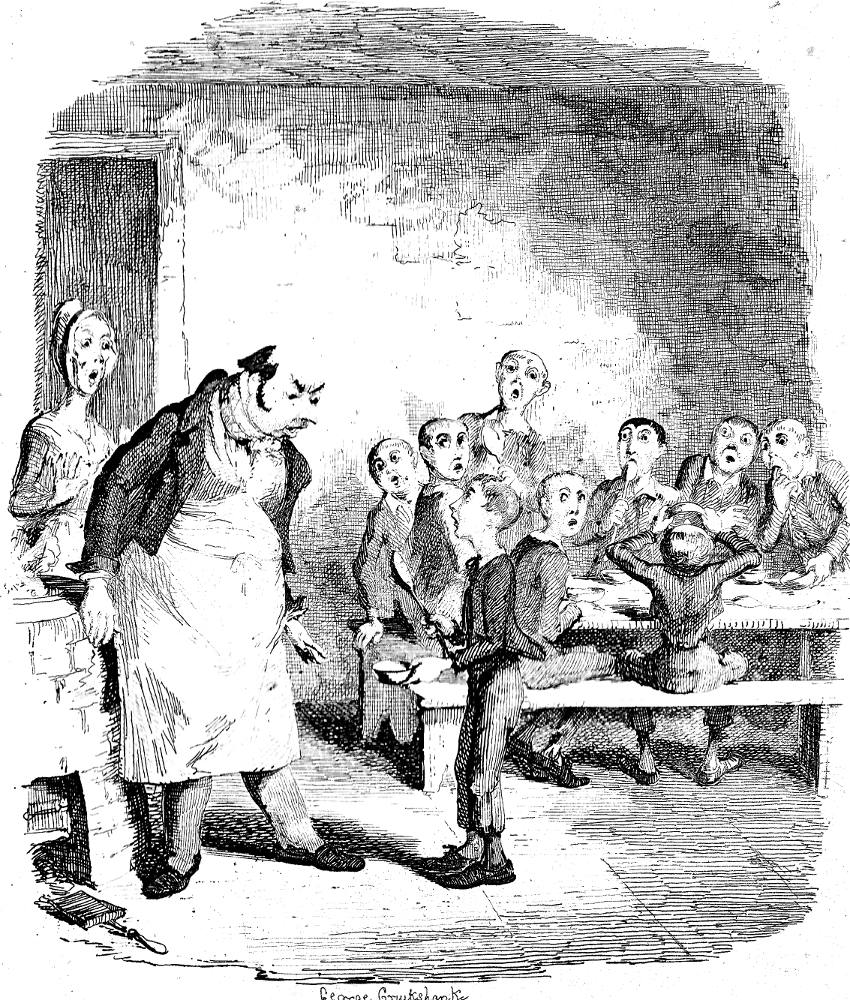

The American satirist re-interprets George Cruikshank's frontispiece for Dickens's The Adventures of Oliver Twist (1837; see below). In Handelsman’s version of the meal in the workhouse, the adolescent inmates all appear well-fed, well-groomed, and comfortably clothed; Oliver stands out because, unlike the others, he has taken far more than he can possibly consume, assuming that he can simply consume the rest later, as if he were at a restaurant. Perhaps that is what the cartoonist is implying, that all of us are so used to abundance that we have come to take excess for granted. After all, only those familiar with both the original illustration and the concept of the doggy-bag can interpret the cartoon.

This New Yorker cartoon mocks attitudes of Handelsman’s American contemporaries at the end of the twentieth century when he surrealistically juxtaposes the modern abundance of food in the Western world with its scarcity in England during the first half of the nineteenth century. In an acerbic series of 14 Alternative Dickens cartoons the socio-political satirist also parodies Dickens, the writer of classic canonical fiction, by outrageously updating such figures as Pip from Great Expectations. As Robert Mankoff pointed out,

Most people have, at best, "Jeopardy!" knowledge of Dickens. But Bud, an Anglophile who spent some years working for Punch [for which he contributed numerous "Freaky Fables"], knew the novels inside out, and his cartoon parodies played with the nineteenth-century graphic style used to illustrated them.

Other titles in the Alternative Dickens series include Scrooge is Audited. Auditor: "As you have no receipt for the turkey allegedly sent to a Mr. Cratchit of Camden Town, I shall disallow it." (17 February 1992) and Alternative Dickens: Pip is Found in Possession of a Controlled Substance (7 January 1991) — as the Bobby pats down down Pip at his carriage door in front of the entire village on the high street, he remarks, "Cannabis resin, or I miss my guess," precisely in the London idiom of Great Expectations. Here is Handleman’s parody of rhetorical style of the opening of A Tale of Two Cities" "I wish that you would make up your mind, Mr. Dickens. Was it the best of times, or the worst of times. It can hardly have been both." Dickens (who looks a little nonplussed as he is unsure as to how to respond to the question) here is just another author having his manuscript critiqued by the reader of a publishing house (Alternative Dickens, 9 March 1987).

Handelsman, born in New York City, studied his craft at the Art Students League and at New York University. Originally a freelance graphic designer, after his marriage to harpist Gertrude Peck in 1950, and becoming a father of three children in Long Island, he moved to England in 1963 to become a full-time cartoonist, working for Punch, the leading magazine of British humour, for eleven years. In 1982, he and his family returned to the United States, where he continued to publish satirical cartoons (often based on iconic images and texts of western culture) in New Yorker until his death in 2007.

Other Representations of the Famous Scene

Left: Cruikshank's February 1837 engraving Oliver Asks for More. Centre: James Mahoney's uncaptioned headpiece for Chapter One, Oliver asks for more (Household Edition, 1871). Right: Harry Furniss's lampoon of the Victorian society's treatment of the poor, Starvation in the Workhouse (1910). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

The Passage from Dickens: "Oliver Asks for More"

For the first six months after Oliver Twist was removed, the system was in full operation. It was rather expensive at first, in consequence of the increase in the undertaker's bill, and the necessity of taking in the clothes of all the paupers, which fluttered loosely on their wasted, shrunken forms, after a week or two's gruel. But the number of workhouse inmates got thin as well as the paupers; and the board were in ecstasies.

The room in which the boys were fed, was a large stone hall, with a copper at one end: out of which the master, dressed in an apron for the purpose, and assisted by one or two women, ladled the gruel at mealtimes. Of this festive composition each boy had one porringer, and no more — except on occasions of great public rejoicing, when he had two ounces and a quarter of bread besides.

The bowls never wanted washing. The boys polished them with their spoons till they shone again; and when they had performed this operation (which never took very long, the spoons being nearly as large as the bowls), they would sit staring at the copper, with such eager eyes, as if they could have devoured the very bricks of which it was composed; employing themselves, meanwhile, in sucking their fingers most assiduously, with the view of catching up any stray splashes of gruel that might have been cast thereon. Boys have generally excellent appetites. Oliver Twist and his companions suffered the tortures of slow starvation for three months: at last they got so voracious and wild with hunger, that one boy, who was tall for his age, and hadn't been used to that sort of thing (for his father had kept a small cook-shop), hinted darkly to his companions, that unless he had another basin of gruel per diem, he was afraid he might some night happen to eat the boy who slept next him, who happened to be a weakly youth of tender age. He had a wild, hungry eye; and they implicitly believed him. A council was held; lots were cast who should walk up to the master after supper that evening, and ask for more; and it fell to Oliver Twist.

The evening arrived; the boys took their places. The master, in his cook's uniform, stationed himself at the copper; his pauper assistants ranged themselves behind him; the gruel was served out; and a long grace was said over the short commons. The gruel disappeared; the boys whispered each other, and winked at Oliver; while his next neighbours nudged him. Child as he was, he was desperate with hunger, and reckless with misery. He rose from the table; and advancing to the master, basin and spoon in hand, said: somewhat alarmed at his own temerity:

"Please, sir, I want some more."

The master was a fat, healthy man; but he turned very pale. He gazed in stupified astonishment on the small rebel for some seconds, and then clung for support to the copper. The assistants were paralysed with wonder; the boys with fear.

"What!" said the master at length, in a faint voice.

"Please, sir," replied Oliver, "I want some more." — Chapter 2, "Treats of Oliver Twist's Growth, Education, and Board," 1846 edition, p. 9-10.

References

Dickens, Charles. The Adventures of Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Chapman and Hall, 1846.

Dickens, Charles. Oliver Twist. Illustrated by James Mahoney. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1871.

Dickens, Charles. Oliver Twist. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1910.

Mankoff, Robert. "A Far, Far Better Cartoon Gag." The New Yorker. 7 February 2012. Accessed 21 September 2016. http://www.newyorker.com/cartoons/bob-mankoff/a-far-far-better-cartoon-gag

Last modified 23 September 2016