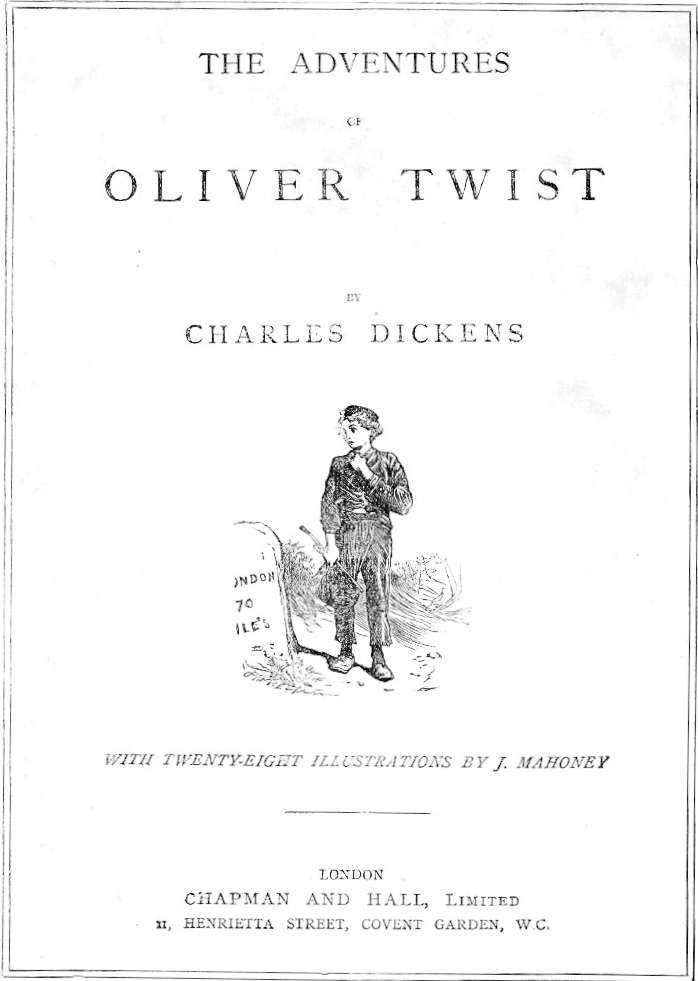

Title-page Vignette, Oliver at the Milestone, on the Highroad to London, for The Adventures of Oliver Twist in the British Household Edition (London: Chapman & Hall, 1871) by James Mahoney. Wood engraving, image 6.4 cm high by 5.5 cm wide or 2 ½ inches high by 2 ⅛ inches wide, vignetted; title-page 9 ¾ inches high by 7 ⅜ inches wide. This initial British Household Edition volume (1871) contains twenty-eight illustrations by James Mahoney. [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

The image of Oliver, alone, unfriended, and in doubt as to his course in life as he puts behind him childhood in the workhouse and his apprenticeship to the grim undertaker is a suitable keynote for the adventures of the orphan in the criminal underworld of the metropolis. [Continued below.]

Passage Illustrated: Oliver at the Milestone, on His Way to London

Oliver reached the stile at which the by-path terminated; and once more gained the high-road. It was eight o'clock now. Though he was nearly five miles away from the town, he ran, and hid behind the hedges, by turns, till noon: fearing that he might be pursued and overtaken. Then he sat down to rest by the side of the milestone, and began to think, for the first time, where he had better go and try to live.

The stone by which he was seated, bore, in large characters, an intimation that it was just seventy miles from that spot to London. The name awakened a new train of ideas in the boy's mind. London! — that great large place! — nobody — not even Mr. Bumble — could ever find him there! He had often heard the old men in the workhouse, too, say that no lad of spirit need want in London; and that there were ways of living in that vast city, which those who had been bred up in country parts had no idea of. It was the very place for a homeless boy, who must die in the streets unless some one helped him. As these things passed through his thoughts, he jumped upon his feet, and again walked forward. [Chapter VIII, "Oliver Walks to London. He Encounters on the Road a Strange Sort of Young Gentleman," 26]

Commentary: The Past is Little Dick; the Future is The Artful Dodger

Having bid his only friend in the world, Little Dick, a tearful farewell at Mrs. Mann's baby-farm, Oliver now strikes out on the high road to London, as so many picaresque heroes before him — including Henry Fielding's Tom Jones and Sir Walter Scott's Jeanie Deanes (figures who, like Roderick Random and Peregrine Pickle, Dickens encountered in his boyhood reading). In his Household Edition volume of David Copperfield (which he illustrated just the year after Mahoney's volume for Oliver Twist came out in the same edition) lead Household Edition illustrator Fred Barnard makes palpable the connection between the earlier picaresque "adventure" of 1837-39 and the classic bildungsroman of 1849-50 by making his keynote the title-page vignette of the wayfaring David, exhausted and in rags, escaping the misery of his working-class existence in the metropolis for the hope of a better, middle-class life with a distant relative in Dover. The similarity in the plates suggests that Barnard may have seen the connection between Sowerberry's runaway apprentice, the victim of a stern stepfather, and the boy who worked in Warren's Blacking at Hungerford Stairs. Both title-page vignettes reveal Dickens's deep concern with abandoned and abused children — a reflection of his own troubled and psychologically damaging experiences with child labour. Then, too, as a student of the great visual satirist William Hogarth, like Dickens Fred Barnard could not have missed the connection between the novelist's picaresque heroes and the protagonists of the visual "progresses" of The Rake's Progress (1733) and The Harlot's Progress (1734). Oliver, after all, is about to enter the world of Henry Fielding's Jonathan Wilde and Hogarth's Gin Lane, inhabited by the criminal mastermind, a gang of pickpockets, a violent housebreaker, and a prostitute with a heart of gold.

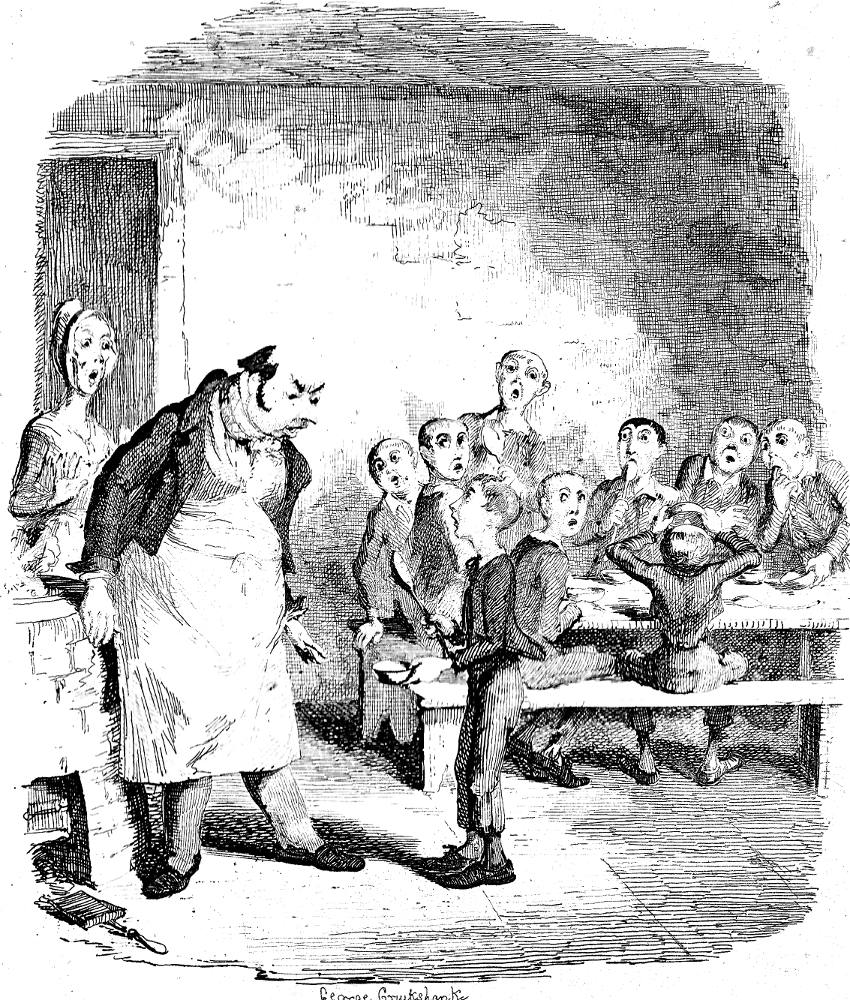

This visual keynote, then, is very different from that of George Cruikshank in the original serial, in which Oliver challenges the workhouse system by asking for more food, the frontispiece for the 1846 edition. Mahoney's emphasis, then, is on Oliver as the victim of the system, the waif and outcast starting out on the high road of life, rather than Oliver as the protester and rebel, as the illustrator attempts from the first to elicit the reader's sympathy for the parish boy. The reader encounters the boy at the start of his journey, and will accompany him in imagination towards his acquisition of class, affluence, and caring family.

Relevant Illustrations from the serial edition (1837-39), Diamond Edition (1867), and Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910)

Left: George Cruikshank's Oliver asking for more (1838). Center: Sol Eytinge's Oliver and Little Dick (1871). Right: Harry Furniss's Charles Dickens Library Edition illustration Oliver's Flight to London (1910). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Scanned images and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Darley, Felix Octavius Carr. Character Sketches from Dickens. Philadelphia: Porter and Coates, 1888.

Dickens, Charles. Oliver Twist. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Bradbury and Evans; Chapman and Hall, 1846.

Dickens, Charles. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 55 vols. Illustrated by F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. New York: Sheldon and Co., 1865.

Dickens, Charles. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Diamond Edition. 18 vols. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

Dickens, Charles. The Adventures of Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 22 vols. Illustrated by James Mahoney. London: Chapman and Hall, 1871.

Dickens, Charles. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. London: Educational Book Company, 1910.

Dickens, Charles. The Personal History of David Copperfield. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 22 vols. With 61 illustrations by Fred Barnard. London: Chapman and Hall, 1872.

Created 12 November 2014

Last modified 5 December 2024