Pre-Raphaelite illustration recreated the aesthetic standards of fine art, an effect largely achieved by careful preparation. Significant efforts were directed at fine-tuning the proofs of the engravings, but most of the work was accomplished using exploratory drawings as a means to consider the possibilities and find the best visual solutions. A large canvas or watercolour might be the product of compositional sketches and drawings, and the same may be said of many of the Pre-Raphaelites’ wood engraved designs for the page. Indeed, the artists were scrupulous in their preparation of the printed image, an approach that stands in marked contrast to the rapid turn-around of illustrators practising in the cartoon tradition, such as George Cruikshank and H. K. Browne (‘Phiz’).

Dante Rossetti was perhaps the most diligent of those working in a Pre-Raphaelite milieu. A perfectionist, he regarded all of his work as worthy of the closest attention, and the greatest effort, he could apply. George Du Maurier recollected how Fred Sandys advised him always to make his illustrations as perfect as he could, and Rossetti would surely have endorsed the belief that ‘patience’ and ‘time’ should be expended until the artist was ‘satisfied’ (Du Maurier 86). In his case, the process of satisfactory completion was the result of producing many preparatory sketches and studies which, Gleeson White observes, ‘were done over and over again’ (164). He was especially careful, perhaps even obsessive, in his development of drawings for the two illustrations he designed for his sister Christina’s volume of poems, The Prince’s Progress (1866). Around twenty works on paper are preserved in Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery (BMAG), and these provide detailed information as to how he approached the task of illustrating Christina’s eponymous poem.

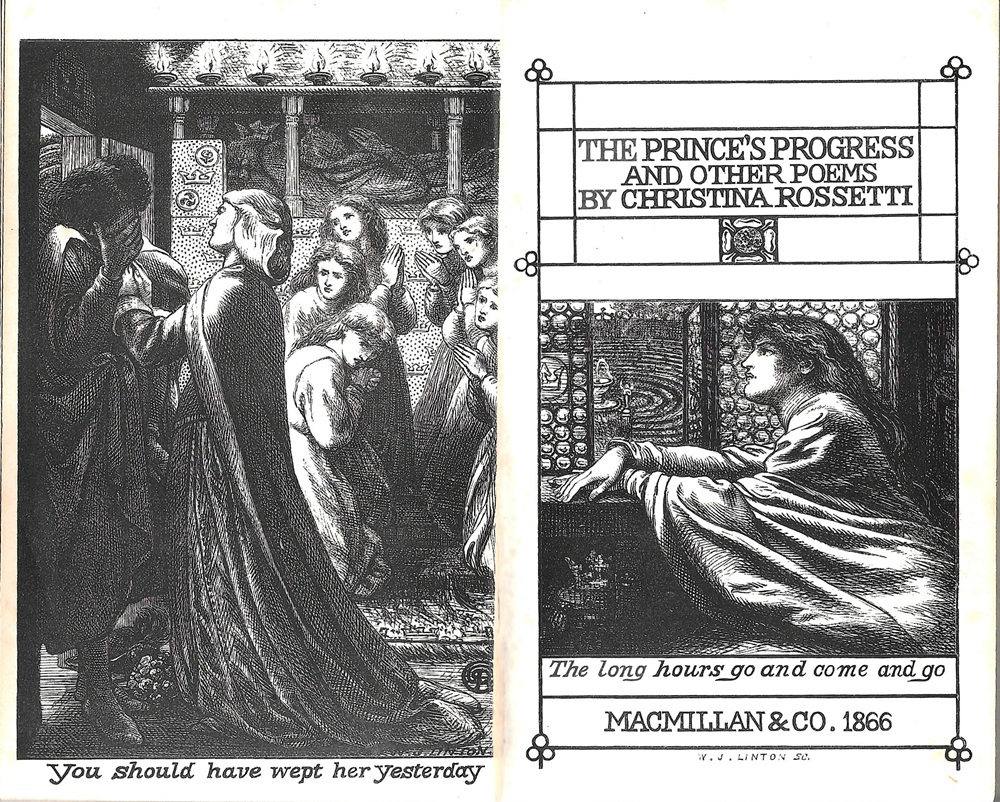

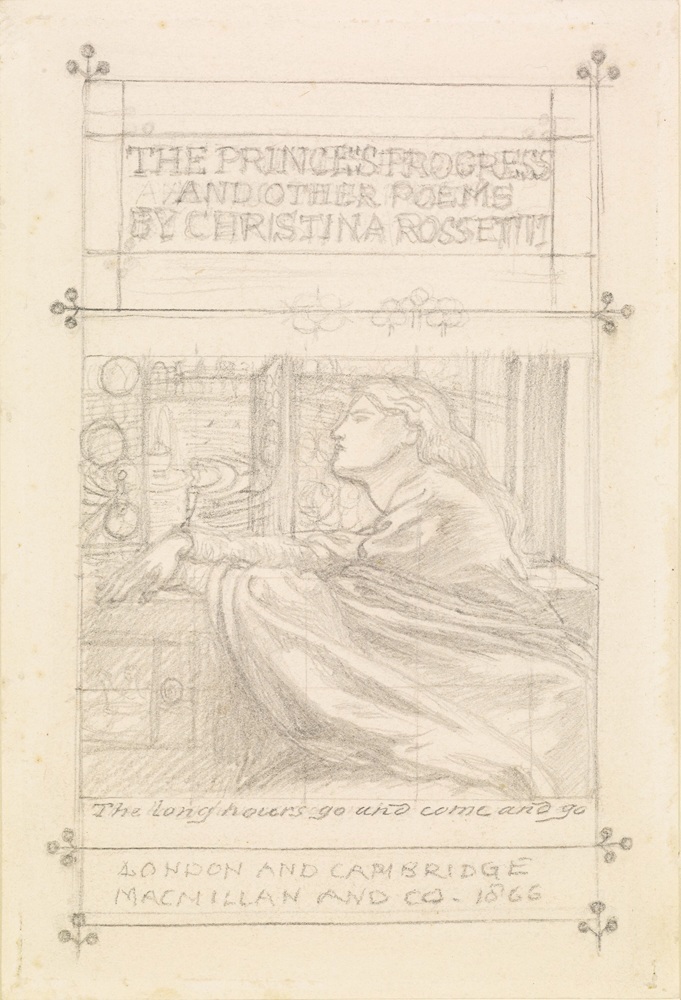

Fig. 1. D. G. Rossetti’s dramatic and imposing illustrations for the opening pages of his sister’s book of poems. [Click on this and the following images to enlarge them, and for more information about them.]

As in his earlier work for Christina’s Goblin Market (1862), Rossetti conceived his designs as a diptych (fig. 1), with one as a pictorial frontispiece (which shows the Prince arriving too late, when his lover is dead), and the other as the title-piece (with the Princess waiting fruitlessly for her suitor to arrive). Each image underwent careful development from his original concept to the finished product and for each design the artist started with generalized compositions and worked on a series of experimental variants. These drawings were slowly produced over the course of 1865, which meant that the book missed its deadline at the end of the year, as originally planned and it was finally published in May of 1866. As with his contributions to the ‘Moxon Tennyson’ (1857), Rossetti rarely held to a schedule, although the quality of the completed designs more than justified his tardiness and acted to promote his sister’s volume by offering the attraction of work by a famous artist; his binding was also a draw (Cooke, ‘Brotherly Hands’). Such visual accessories convinced Macmillan to publish (Morgan 64) and made a calculated pitch at the taste of the readership, an approach that built on the earlier success of Goblin Market, which was also published by Macmillan. But how, exactly, did Rossetti develop his illustrations? This process can be explained by considering them as two narratives.

The Prince’s Tale

In his drawings for the frontispiece he focused, first of all, on establishing ways of representing the story as the Prince arrives. Christina describes her character’s behind-time appearance in a question, ‘What is this that comes through the door … ’ (Prince’s Progress, 27), and Dante emphasizes the physicality of that moment in his first, relatively finished design (which he based on a loose pencil sketch), by showing the character as he steps over the threshold: the door is clearly represented and the Prince’s final urgency is highlighted by depicting him as a dynamic figure who steps forward, holding a bouquet with a look of incomprehension on his face as the servant who speaks to him in the poem holds out her hands as if to stop his forward movement.

This preliminary drawing is a rather crude attempt to find an appropriate visual formulation. The effect is melodramatic, and the characters clumsily modelled (fig. 2). There are also some distinct differences between the text and the illustration: in the poem she is being carried by ‘Veiled figures’ (PP, 27), but here she is already installed in her tomb; Christina does not make clear who is speaking the long reprimand to the Prince, but in Dante’s design the voice is embodied in the form of the primary female servant. This is, in other words, an important working first step – the thinking-through of the poem’s material and the conceptualization of the subject in a process that Rossetti described, in speaking of the need for clear ideas in any work of art, as ‘fundamental brainwork’ (Caine 249).

Three of Rossetti’s preparatory studies for his sister’s poem: fig. 2 (left) shows his initial composition and blocking; fig. 3 (centre) represents a refinement, with a growing emphasis on psychology rather than storytelling; and fig. 4 (right) is a fluid development, very close to the final illustration.

However, significant changes have been made in what is probably the second version. This time the door has been diminished (fig. 3). The Prince’s attitude has changed so that his hand is now over his face; the arresting gesture of the servant has become one of forceful reproach; her figure has been animated with greater movement and repositioned out of profile; and the mourners in the background have been rearranged into six characters positioned hierarchically on either side of a reading desk.

This arrangement was further refined, moreover, in the third version of the scene (fig. 4). The crayon drawing has far greater fluency than the first, and in this design the final arrangement is made: the lectern has been removed, and the Prince’s and attendant’s poses are the ones carried forward. Tellingly, the Prince’s face was concealed by his left hand in the second design, but his right in the third; his bouquet, which he carried in his right hand in the previous drawing has now disappeared – although it reappears on the floor, having been dropped in despair, in the published engraving.

We can see, then, how Rossetti progresses from his early experimentation to a final solution in which he presents a highly focused, dramatic encounter that enshrines the lines given in the caption, ‘You should have wept her yesterday,’ the line delivered in reprimand by the servant in the closing stanza (PP, 30). The effect is overpoweringly intense, and it is important to note that Rossetti had to create visual identities to embody Christina’s lines, not only visualizing the attendant (as noted earlier), but also the Prince. Indeed, it is important to stress the fact that the poet does not describe the Prince’s reaction to finding his beloved is dead: the final parts of the poem are entirely given over to the attendant’s admonishment and give no clue as to how he might respond. His grief is therefore entirely Dante’s invention as he infuses the character with an emotional depth which is otherwise missing in a narrative that stresses the Prince’s idleness and unreliability. Clearly, the artist understood the need to close the Prince’s (non) progress with a cathartic emotional effect, and it is not surprising that he worked on detailed studies of the male protagonist, experimenting with different poses and including the eloquent anguish of the single hand placed over the face (figs. 5, 6, 7). The reproachful servant and the keening maidens, as foils to the Prince’s figure, also underwent development as Rossetti sought to amplify his psychological effects (figs. 8, 9). The kneeling girls, especially, are used to add further stratum of dramatic meaning; despite having identical faces, each has a different facial expression that varies from curiosity to the angry and resentful look of the figure nearest to the attendant.

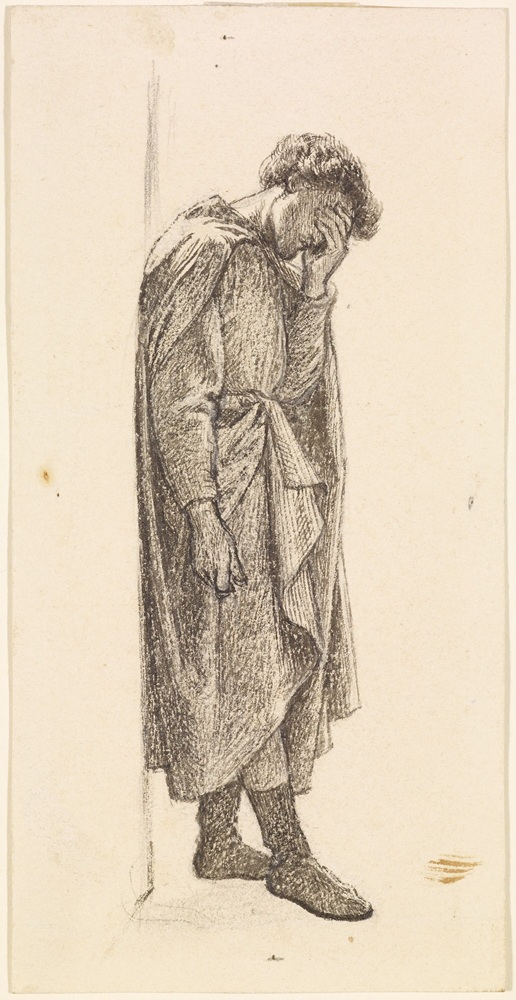

Rossetti applied a huge amount of effort to the production of his graphic designs, studying individual figures in detail. The three designs shown here represent stages in his characterization of the Prince’s suffering: fig. 5 (left) depicts an angst-ridden, hurrying Prince, his fists closed in anguish; figs. 6 and 7 (centre and right) depict the final solutions, with the final one fig. 7 being the artist’s concluding choice.

Two more preparatory drawings, this time in the development of the mourning figures: fig. 8 (left) is a detailed study of the attendant who delivers the crushing lines (‘You should have wept her yesterday’) and fig. 9 (right) depicts the mourners.

The quality of the figure studies indicates once again the conscientious way in which Rossetti prepared his illustration as if it were a small-scale painting in black and white, and his creation of these characters emphasises his willingness to develop, alter or add to the literary source. By materializing the poet’s characters in a highly emotionalized scene as suffering figures he greatly intensifies the poem’s impact and, as Maryan Wynn Ainsworth remarks, significantly ‘expanded the meaning’ of the text (73). Indeed, this strategy, embodied in the development of the sketches and studies as he worked through possible solutions, is a prime example of the artist’s belief that all illustration should be interpretive and expansive, allowing the illustrator to ‘allegorize’ on his ‘own hook’ while not ‘killing for oneself and everyone a distinct idea of the poet’s’ (Hill, Letters to Allingham, 97).

Rossetti positions this design as the first the reader/viewer will see, using it as a proleptic device that establishes its narrative and draws the reading eye forward into the text. The question posed is a simple one: if the Prince arrives so late, what has taken him so long? Christina’s poem provides the narrative explanation. But this is only half of the equation; having condensed the Prince’s story into a resonant design, the artist focuses in the second image, the pictorial title page, on the Princess’s back-story – and how she arrived at the situation depicted in the frontispiece.

The Princess’s Tale

The poem is clear about the Princess’s status: all she has to do is wait, and finally die, in anticipation of her beau’s arrival. This situation is a familiar trope in Victorian culture. Its literary source is probablyTennyson’s ‘Mariana,’ which was first published in 1837 and reissued in the Moxon edition of 1857, and its visual formulations are widespread in Victorian painting and illustration.

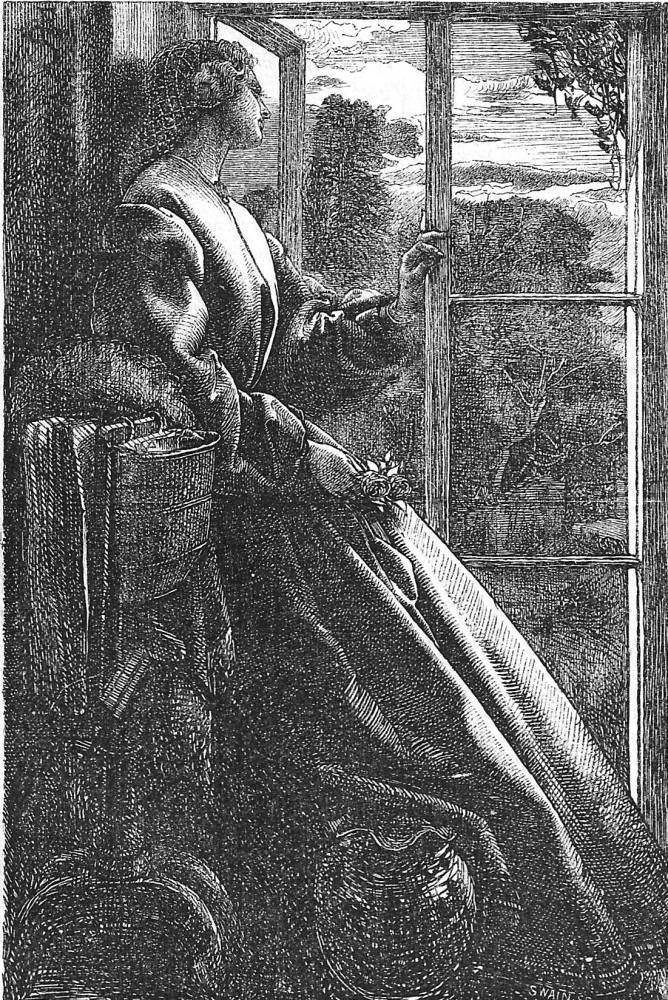

Rossetti was responsive to this pre-existing pictorial code and produced his title-page version of the ‘waiting woman’ for The Prince’s Progress in a context that included Frederick Sandys’s illustration If he would come today (fig. 10, The Argosy. Midsummer 1866, facing 336) and J. E. Millais’s painting, Waiting (fig. 11, 1854, BMAG). Rossetti would also produce numerous paintings on the same theme – notably The Blessed Damozel (fig. 12, Harvard Museums, 1871–78), which illustrates his own poem on the travails of endless waiting for the male lover to arrive. However, in working on his sister’s poem he seems far from sure as to how he should respond to her lines and, as in his work for the pictorial frontispiece, experimented with a number of variants.

The ‘waiting woman’ motif. fig. 10. Sandys’s If he would come today; fig.11 Millais’s Waiting; and fig. 12. Rossetti’s The Blessed Damozel.

His earliest attempt, like that for the pictorial frontispiece, is a compositional rough in which he adopts the familiar trope of a woman looking out through a window – as in Sandys’s From my Window (fig. 13, Once a Week, 1861, 238) – and makes her into an entirely passive type, a literal illustration of the Prince’s lines as he contemplates his prospective ‘bride … in her maiden blooms’ who ‘Keeps she watch … watch for me asleep and awake’ (PP, 2). Once again, Rossetti starts off by establishing the dramatic situation – a woman waiting for a man to turn up (fig. 14). However, he quickly shifts his attention from the narrative to its psychology, focusing on the Princess’s state of mind rather than her place within the story.

fig. 13. Sandys’s From my Window; and fig. 14, Rossetti’s waiting Princess as she anticipates the arrival of the Prince, an early, static treatment of her situation.

In the next drawings he makes her into a more dynamic and complex figure than the text implies. Typically, this process involves visualizing some information while adding other, weighted details. He reproduces the line that ‘There was no hurry in her hands’ (PP, 30), endowing her with crossed hands to suggest a sort of languid patience, but at the same time he highlights her yearning by giving her outstretched arms, as if she is imagining how she might extent them to eliminate the space and time between her and the Prince, and to embrace him (fig. 15). This gesture infuses the situation with urgency that is missing from the text and it is interesting to note that it may represent one of Rossetti’s unacknowledged borrowings from the art of his wife, Elizabeth Siddal. There is certainly a close relationship between Siddal’s drawing of an unidentified subject (fig. 16, circa 1855, the British Museum, London), which shows a female figure reaching out through a window, and Rossetti’s treatment of the same situation; he even includes his own version of Siddal’s fretted windows. This connection has not been noted before but is yet another example of the symbiosis working between the two artists and the debt Rossetti owed to his overlooked companion (Cooke, Moxon Tennyson, 191–93).

fig. 15 Rossetti’s study of the Princess with outreached arms, and fig. 16. Siddal’s drawing of an unknown subject that may have been a source for Rossetti’s design.

The yearning arms are indeed an important part of Rossetti’s emphasis, Lorraine Janzen Kooistra observes, on the travails of ‘physical consummation’ (79). Endowing her with this gesture, Rossetti especially highlights the poem’s suggestion of the Princess’s sexual desire, as if she is reaching out to try to encompass and consummate the sexual feelings encoded in the text:

By her head lilies and rosebuds grow;

The lilies droop, will the rosebuds blow?

The silver slim lilies hang the head low …

Red and white poppies grow at her feet

The blood-read wait for sweet summer heat,

Wrapped in bud-coats hairy and neat;

But the white buds swell, one day they will burst

Will open their death-cups drowsy and sweet –

(PP, 2-3).

Christina paradoxically uses phallic imagery to suggest frustrated desire as the lilies ‘grow’ and ‘droop,’ while the swelling buds never get to ‘burst’ and the ‘death-cups drowsy and sweet,’ the symbols of erotic satisfaction, are forever kept in check. Dante makes no attempt to visualize these lines directly, but offers an equivalent in the form of the Princess’s reaching, in part urgent but terminated in the closure of her hands, literally reaching for a consummation that is forever stalled and obstructed. The hands only ever enclose the Princess’s own fingers. Moreover, Rossetti suggests other sexualized nuances, a matter of longing and frustration which he inscribes in the treatment of her figure, in the introduction of an intent gaze, in the setting, and in the view from her window.

Left: fig.17. Rossetti’s drawing of the Princess with an angular jaw; and fig. 18, the completed figure as she appears in the final title page.

Three examples of ‘strong women’ with pronounced jawlines, as practised elsewhere in Rossetti’s oeuvre: fig. 19 (left) Beata Beatrix; fig. 20 (centre) Lady Lilith; and fig. 21 (right) Monna Vanna.

To suggest the Princess’s suppressed sexuality he makes her into an eroticised type. In the first two drafts of the illustration he depicts her with a rounded face (figs. 14, 15) which, within the context of Victorian culture, implies domesticity and a matronly submissiveness. However, in the later versions he has endowed her with the angular jaw, accentuated by the turn of her head, which implies a sexual self-awareness and strength – imagery that would later run through his paintings and especially in works such as Monna Vanna (fig. 21, 1868, Tate Britain), Beata Beatrix (fig. 19, 1864–70, Tate Britain), and Lady Lilith (fig. 20, 1866–68, Delaware Art Gallery, Wilmington). Christina thought that the figure’s ‘phiz’ resembled her own, with the suggestion that the illustration might be a reminder of the author’s romantic disappointments as her various relationships failed; such an approach would be incredibly insensitive on the part of her brother, were it true. Likelier, Dante was simply offering a particular interpretation of the poem, showing his character as a forceful woman, with sexual desires, rather than a passive recipient of male (in)action.

fig. 21 Rossetti’s drawing of the Princess with short hair, a sign of modesty; and fig. 22, the Princess with long hair, literally ‘letting her hair down’ in anticipation of sexual activity.

He confirms this reading by experimenting with the detail of the character’s hair. Hair, like other physical features, was conventionally read in the Victorian age as an indication of personality, and it is noticeable that in his studies Rossetti shows his figure having short hair and as a woman with her hair cascading down her back. The first signals modesty, the second erotic desire. Adopting the second formulation, the artist stresses the notion of the Princess’s (frustrated) sexuality.

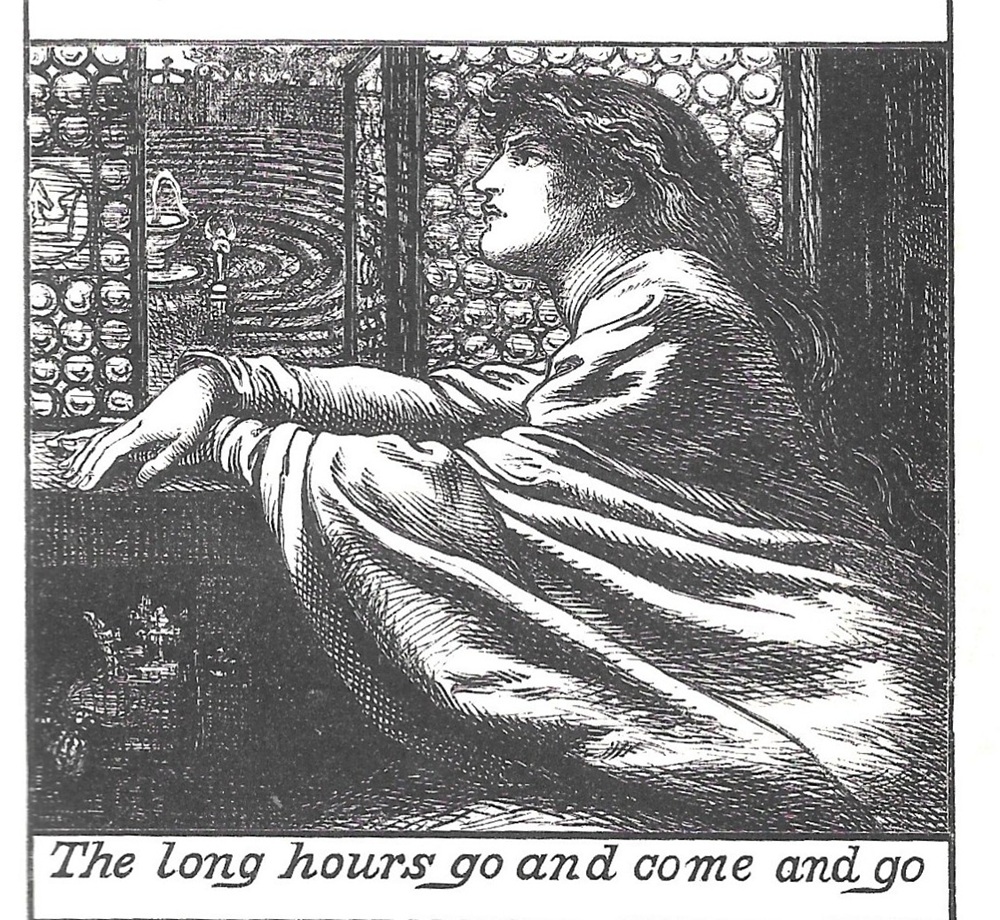

He further develops symbolic representations of her confounded desire in the form of emblematic details, and in his use of expressive space. Rossetti’s placing of the character within a narrow aperture and constrained by the small opening of the window is a visual sign of her psychological inertia. The author speaks of the character being ‘Spell bound’ in one ‘white room’ (PP, 2), and Dante focuses the connection between physical and metaphorical imprisonment. Most telling, though, is his deployment of the circular forms that appear in the roundels of the window and in the maze appearing in the narrow space of the garden, each of which appears in the final compositional studies. These closed lines connote the character’s unchanging experience as her desires are unsatisfied; especially significant is the maze, which acts, in the words of Gail Lynn Goldberg, to suggest a ‘perplexity’ of mind (151). Kooistra also sees a confounding of ‘sexual fulfilment’ in the contrast between the figure of the fountain (an obvious male symbol, with its gushing water), and the Princess’s sexless isolation as she remains in ‘her enclosed virginal space’ (81).

This use of the maze suggests other readings too. In part a sexual metaphor, it acts to symbolize spiritual journeying – as in Quarles’s Emblems (Kooistra 79, 81) – and to link the Princess’s unresolved quest for sexual experience with the Prince’s endless dithering through a frustrating landscape of tedious irresolution. Used by Rossetti as a polysemic sign, the maze inflects the poem with another ‘fleshly reading’ (Kooistra 81) while still acting as a suggestion of other meanings, notably the need to make the best of opportunities.

We can see, in short, how Rossetti developed his illustrations for The Prince’s Progress, producing a diptych of highly resonant images that greatly expand the implication of the volume’s opening poem. These visual texts developed over time and can be charted in the changing formulations of his preparatory drawings – drafts of his emerging ideas as he struggled to arrive at a typically idiosyncratic reading which was nevertheless a faithful, and penetrating, treatment of his source material. He may have regarded his literary texts as a ‘hint and an opportunity’ (W. M. Rossetti, Family Letters, 189) for his imaginings, but he never undermined the integrity of his sister’s troubling parable of desire, frustration, and the need to seize the day.

Bibliography

Primary

The Argosy (Midsummer 1866).

Once a Week (1861).

Rossetti, Christina. Goblin Market. London: Macmillan, 1862.

Rossetti, Christina. The Prince’s Progress. London: Macmillan, 1866.

Tennyson, Alfred. Poems (‘Moxon Tennyson’). London: Moxon, 1857.

Secondary

Ainsworth, Maryan Wynn. Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s Double Work of Art. Yale: Yale University Press, 1976.

Caine, Thomas Hall. Recollections of Dante Gabriel Rossetti. London: Elliot Stock, 1882.

Cooke, Simon. ‘“Brotherly Hands”: Dante Rossetti’s Artwork for His Sister Christina.’ The Review of the Pre-Raphaelite Society 14, no. 3 (2006): 15–26.

Cooke, Simon. The Moxon Tennyson: A Landmark in Victorian Illustration. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2021.

Du Maurier, Daphne. The Young George Du Maurier: Letters 1860–67. London: Peter Davies, 1951.

Goldberg, Gail Lynn. ‘Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s “Revising Hand”: His Illustrations for Christina Rossetti’s Poems.’ Victorian Poetry 20 (1982): 145–159.

Hill, George Birbeck. Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s Letters to William Allingham, 1854–1870. London: Fisher Unwin, 1897.

Kooistra, Lorraine Janzen. Christina Rossetti and Illustration (‘Moxon Tennyson’). Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2002.

Morgan, Charles. The House of Macmillan, 1843–1943. London: Macmillan, 1944.

Rossetti, William Michael. Dante Gabriel Rossetti: His Family Letters. London: Ellis & Elvey, 1895.

White, Gleeson. English Illustration, ‘The Sixties’: 1855–70. London: Constable, 1897.

Created 1 August 2025