The Seed of David by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882), depicting, from left to right, The Nativity; David the Psalmist; and David preparing to Fight Goliath. 1858-64. Oil on canvas, arched top, central portion 90 x 60 inches; wings each 73 x 24 1/2 inches. Llandaff Cathedral. Click on image to enlarge it.

Rossetti's Llandaff Cathedral altarpiece, The Seed of David, confirms that his use of typology was not merely an early experiment which he soon abandoned. For although he did not believe in the literal truth of typology (or that of Christianity, for that matter), Rossetti continued to use prefigurative symbolism in his important religious painting. The central panel representing an Adoration of the Magi is flanked by two representations of David, that on the left showing him as a boy, sling in hand, that on the right as crowned king. As the artist explained in a letter to Charles Eliot Norton written in 1858 when his conception of the triptych was taking form, he intended to paint "the Nativity; for the side pieces to which I have David as Shepherd and David as King — the ancestor of Christ, embodying in his own person the shepherd and king who are seen worshipping in the Nativity."[July 1858; Letters, I, 338]. Creating the kind of complex play upon types that one encounters in the poetry of his sister Christina, Rossetti makes David prefigure both Christ and all men who will worship him. David the shepherd, whom he later described as advancing "fearlessly but cautiously, sling in hand, to take aim at Goliath" ( Rossetti Papers, 1862 to 1870, ed. W. M. Rossetti [London, 1903], 51). David thus stands in a complex temporal and symbolic relation to the central panel of the picture: he is, first David, the hero who slew Goliath; second, the ancestor of Christ; third, a type of Christ slaying Satan; fourth, a type of all men who will worship Christ; and, fifth, also alluding to the Beatitudes — the poor man who attains a true kingdom. As Rossetti further explained in a description of the work presumably sent to the Llandaff authorities, "The Shepherd kisses the hand, and the King the foot, of Christ to denote the superiority of lowliness to greatness in his sight; while the one lays a crook, the other a crown, at his feet." This emblem of "the superiority of poverty over riches in the eyes of Christ" effectively echoes and reinforces the historical juxtapositions of the side panels to each other and to the center (Letter to Charlotte L. Polidori, 25 June 1864; Letters, II, 508).

The right-hand panel also stands in a complex relation to the nativity. First of all, David is now "a man of mature years, still armed for battle, and composing on his harp a psalm in thanksgiving for victory" [Rossetti Papers, 51]. Second, he is a type not only of Christ as king but also of all kings who must yield allegiance and give thanks to God. Third, he is a type of the three kings who came to adore the infant Jesus. Typology's capacity to endow the literal fact or event with further meanings here functions as importantly as its ability to relate various times. By juxtaposing the Old Testament history of David, the point in time at which Christ enters human history, and all subsequent history, Rossetti has managed to create an effective devotional image which emphasizes the continued presence of God's plan to save man from the consequences of his fall.

According to William Michael Rossetti's diary for 1861, his brother did "not mean his triptych to be considered as a Navity or Adoration, but rather Christ sprung from high and low and Lord of high and low" (Quoted by W. M. Rossetti, Ruskin, Rossetti and Preraphaelitism [London, 1899], 283 from his diary entry of 7 September 1861). As the painter himself explained, "the centrepiece is not a literal reading of the event of the Nativity, but rather a condensed symbol of it" (Rossetti Papers, 51). and a glance at the picture shows precisely what he meant. For in addition to establishing a series of relations between side and center panels, he also made use of typological symbols in the nativity scene itself. For example, when the shepherd presents his crook in homage to Christ, the greater Shepherd, he places it in such a way as to touch an apple from which a worm, an image of Satan, appears. This action prefigures the way Christ himself as Good Shepherd will finally conquer Satan and death while it simultaneously reminds us of the prophecy of bruising the serpent. This allusion to the Fall (with worm and apple) thus extends the temporal limits of the subject back to the beginnings of human time and forward to the Last Judgment. Furthermore, as Professor Horton Davies has pointed out to me, this shepherd's crook also prefigures the bishop's symbol of authority and discipline by which the pastor pastorum disciplines the wayward members of his flock — symbolism appropriate for the cathedral church in which it is displayed.

The Seed of David presents what is essentially a vision not of the event, but of the event's full meaning when understood within the context of sacred history. Characteristically, Rossetti employs typology to provide that context. Recognizing the visionary nature of this picture has the advantage of revealing an important connection between this apparently atypical work and a large number of his other paintings. Typology for him, as for Hunt, was intimately related to prophecy and vision, and it was this relationship which made it especially congenial to Rossetti, who remained fascinated by moments of vision throughout his career.

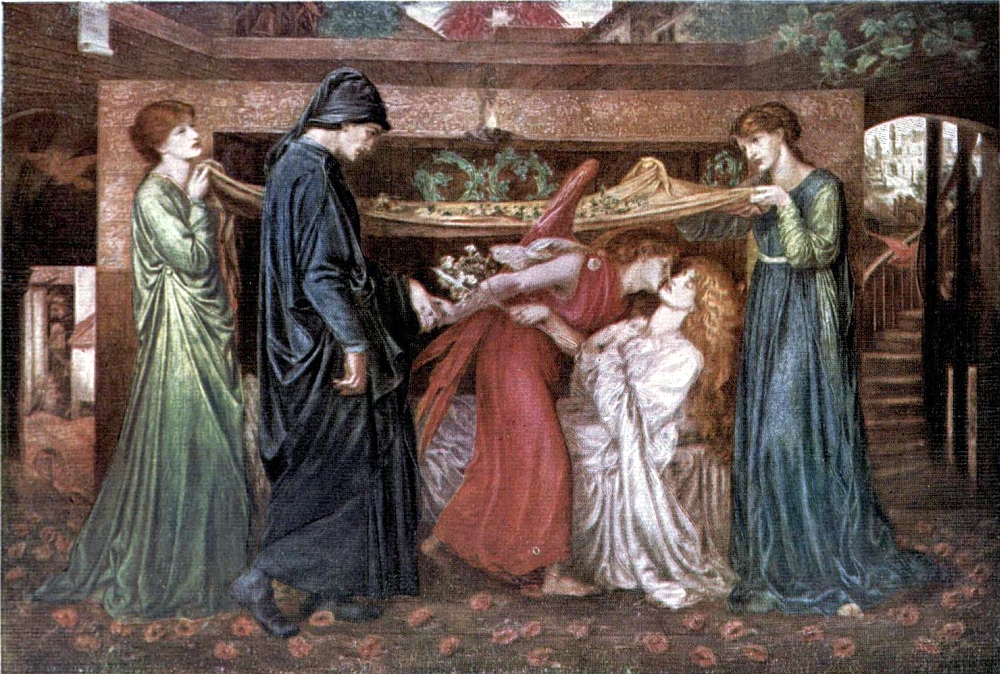

Dante's Dream at the Time of the Death of Beatrice by Dante Gabriel Rossetti. 1871-81. Oil on canvas, 83 x 125 in. Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool.

In fact, a large number of his important pictures depict some sort of vision, prophecy, conversion, or first sight: his three early illustrations to Poe's "The Raven" (1846-7) reveal a concern with visionary experience as do Dante's Vision of Matilda Gathering Flowers (1855), Dante's Vision of Leah and Rachel (1855), The Blessed Damozel (1875-8), Dante's Dream at the Time of the Death of Beatrice, various versions of which were painted in 1856, 1871, and 1880, and Sir Launcelot's Vision of the Sanc Grael (1857).

Left: Beata Beatrix. 1864-70. Oil on canvas, 32 x 26 inches. Right: Dante's Vision of Rachel and Leah. 1855. Watercolor, 14 x 12 ½ inches, Both courtesy of Tate Britain.

Closely related to this interest in visions and the visionary is Rossetti's interest in portrayals of illumination. The most importance of these climactic moments of vision appear in his various versions of the annunciation theme and also in Mary Magdalen at the Door of Simon the Pharisee (1858).

Left: Mary at the Door of Simon the Pharisee. Right: Found. Begun 1853 or 1859. Oil on canvas, 36 x 31 1/2 inches. Courtesy of the Delaware Art Museum, Wilmington, Delaware Samuel and Mary R. Bancroft Memorial, 1935 DAM# 1935-27

More secular versions of such experience occur both in Found and The Gate of Memory (1864), in which the sight of children playing provides the woman with a sight of her own past — a moment of recognition somewhat analogous to Hunt's Awakening Conscience. Hamlet and Ophelia (1858), Taurello's First Sight of Fortune (1849), and Beatrice Meeting Dante at a Marriage Feast (1851) all present different approaches to the problem of depicting a climactic encounter, while The Salutation of Beatrice (1859) and Paolo and Francesca portray climactic moments which change a person's entire life — for Paolo and Francesca the kiss is their conversion, their falling in love, which leads to their place in hell, while Dante's own encounter with Beatrice offers an opposing vision, a sight of the higher love which will lead him to Paradise.

Paolo and Francesca. 1849-62. Mixed media, 12 l/2 x 23 3/4 in. Cecil Higgins Art Gallery, Bedford. (A version is also in the Tate Gallery).

Many of the works for which Rossetti is probably best known — his depictions of the Fair Lady — also present such moments of vision or first-sight. Whereas The Beloved (1865-6) portrays both the content of a vision of the loved one and the one who is experiencing the vision, A Vision of Fiammeta (1878) apparently records the painter's own vision of beauty rather than a character experiencing a moment of illumination; but since Fiammeta, like so many of these women, is deeply immersed in reverie, one cannot easily distinguish between the two.

Left: La Donna della Fiamma. 1870. Colored chalks, 39 5/8 x29 5/8 inches. Manchester City Art Galleries. Right: The Beloved. 1863. Oil on canvas. Tate Britain.

Rossetti always found himself drawn to such moments of vision, and his interest clearly derived from the most central parts of his personality and was not the result of a concern with typology and prophecy. Rather, his fascination with such experience grounded his use of typological symbolism, so, although both Hunt and Rossetti painted religious pictures employing types, Rossetti chose to stress the symbolic nature of his work, while Hunt stressed the balance between both literal and symbolic.

Holman Hunt as "The Pre-Raphaelite of the World" by Vanity Fair's Spy.

For Collins, Collinson, and Millais, their early experiments with typological symbolism had little impact on their later careers, something particularly interesting in light of the fact that both Collins and Collinson were deeply religious. Only Hunt and Rossetti, so different as men and artists, continued to be fascinated by prefigurative symbolism. although the works of both men demonstrate they knew how to exploit the full capacities of such imagery, Rossetti employed it chiefly because it could unite different times while Hunt did so largely because it could unite matter and spirit, realism and symbolism. For Hunt, whom a Vanity fair described as "The Pre-Raphaelite of the World," typology provided a means of creating an art replete with meaning.

Created 2001 last modified 31 October 2020