[Click on image to enlarge it.]

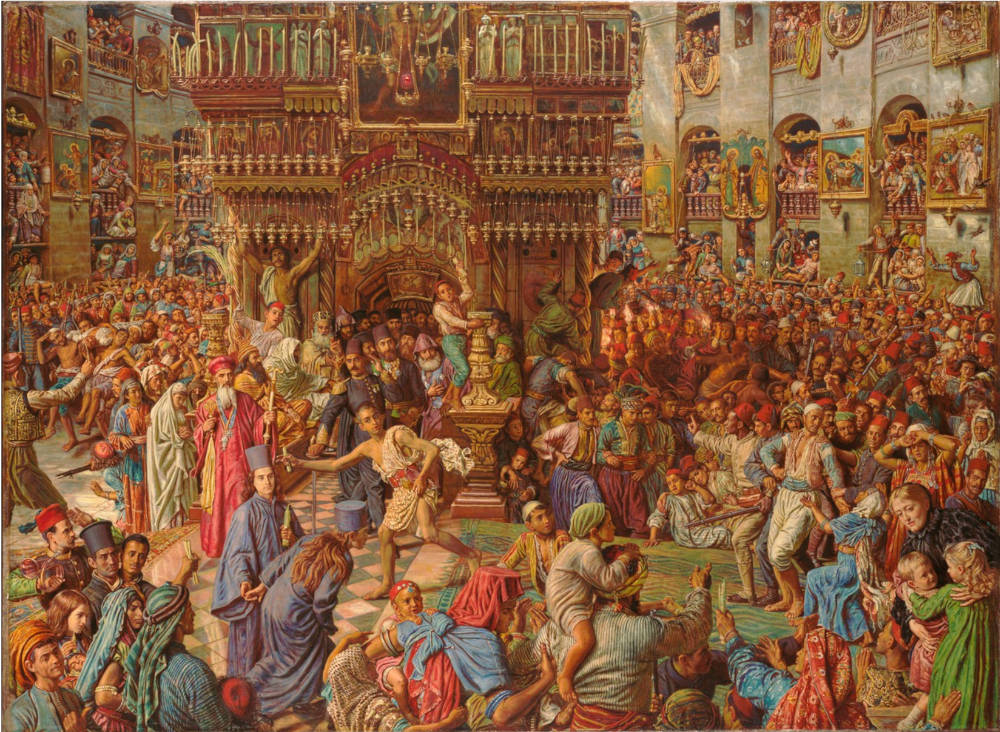

The Miracle of the Holy Fire, which Hunt painted almost forty years after first seeing the ceremony in Jerusalem, is the most explicitly satirical, most Hogarthian of his pictures. For him the Easter Eve rite in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre represented the degeneration of authentic religious wonder into selfishness, superstition, and worse - into mad frenzy and unchristian violence. During the ceremony the Greek Patriarch in the holy city produced a candle supposedly lit by heavenly powers or angelic visitation, and for the painter it had a specific topical reference. It was his response to those ecumenically minded Anglicans who proposed in the late 1870s and '80s to join with the Greek, Armenian, Russian, and other Orthodox Churches. As he wrote to Tupper in 1877, "How Stanley can desire union for our Church with the Greek perpetrators of miraculous fire I can't understand" (15 July 1877; London (Huntington MS.). By the time he came to paint this scene emblematic of institutionalized superstition, much of its topicality had been lost, but it still bore important meanings for him, since it satirized established, conventional Christianity. Hunt, who had attacked the corruption of English missionary practices in his 1858 pamphlet, returned to the fray four decades later as a pamphleteer in paint.

The Hogarthian tone and method of The Miracle of the Holy Fire are emphasized for the spectator by the catalogue Hunt prepared — or had prepared under his supervision — for the exhibition of his picture at the New Gallery . He included a key-plate, a general explanation of the ceremony, and an anthology of travellers" descriptions of it throughout the ages. In explaining the ceremony, he displays sympathy for the naive beliefs of the superstitious pilgrims, most of whom, he points out, "have accumulated the means for the sacred journey only by years of self denial. Of child-like nature they long to see the Miracle as Heaven's token of their church's supremacy." He did not scorn this superstition, for he recognized and respected the element of faith it contained, but he had only hatred for the spiritual blindness, selfishness, and cruel violence this misguided faith produced — something he makes abundantly clear in the travellers" descriptions he included in his pamphlet. He quotes, for example, a long narrative of the ceremony by Henry Maundrell, "a fellow of Exeter College, Oxford,' which emphasizes the madness and violence of the participants. According to Maundrell, the great prize for which the various Christian sects battle at the ceremony

is the command and appropriation of the holy sepulchre, a privilege contested with so much unchristian fury and animosity, especially between the Greeks and the Latins, that, in disputing which party should go into it to celebrate their mass, they have sometimes proceeded to blows and wounds even at the very door of the sepulchre, mingling their own blood with their sacrifices, an evidence of which fury the father guardian showed us a great scar on his arm, which he told us was the mark of a wound given him by a sturdy Greek priest in one of these unholy wars. [Miracle, 5]

Maundrell mentions the rite's history of violence but himself only reports the "Bedlam" and the way he observed the riotous crowd "making a hideous clamour very unfit for that sacred place, and better becoming Bacchanals than Christians" [Miracle, 5-6].

In contrast, the description by Curzon, which follows immediately upon that by Maundrell, relates an actual "ferocious battle" he saw in 1834. According to Curzon, when he left the shrine afterwards he found a scene of terrible carnage:

In the court in the front of the church the sight was pitiable: mothers weeping over their children — the sons bleeding over the dead bodies of their fathers — and one poor woman was clinging to the hand of her husband, whose body was fearfully mangled. Most of the sufferers were pilgrims and strangers . . . The whole court before the church was covered with bodies, laid in rows, by the Pasha's orders, so that their friends might find them and carry them away. As we walked home we saw numbers of people carried out, some dead, some wounded and in a dying state, for they had fought with their heavy silver ink-stands and daggers. [Miracle, 8-9]

By appending these long passages to his exhibition catalogue, Hunt not only made his views of such religious lunacy quite clear but also managed rather deftly to forestall charges that he had exaggerated.

Both these travellers" reports and his own key-plate function somewhat in the manner of Hogarthian inscriptions, turning the events depicted within the picture into a series of satiric emblems. In fact, when Hunt came to design his frame, he included "two scrolls, upon which is written a description of the strange incidents of the ceremony." Furthermore, employing the Hogarthian device of the visual pun, he also included "in the pediment of the frame the seven-branch candlestick as a symbol of religious truth for the illumination of the people, which instead of giving light is negligently left to emit smoke, thereby spreading darkness and concealing the stars of Heaven" (II.385). These symbols on the frame make clear that the scene taking place within its confines shows that when men seek material versions of holy illumination and holy inspiration they only extinguish God's true sacred fires. Like Tennyson's "Holy Grail," The Miracle of the Holy Fire demonstrates that when men seek a cheap and easy road to salvation, they inevitably put out the divine light within themselves.

The chief actions within this bizarre and crowded picture comment ironically upon the supposedly sacred ceremony in which God's spirit descends upon men. The first figure we catch sight of is, according to the key-plate, "an Arab boy in flight from the soldiers" who wish to arrest him for rioting or robbery, while in the prominent group in the right-hand corner we catch sight of a young Bethlehemite "who has been seized by Turkish soldiers and accused as one of the rioters." Behind him, and farther to the right, stands his bride, "desire for whose silver ornaments may have been the sole cause of the husband's apprehension by the 'Zuptich.'" Behind this group, almost obscured by the chaos within the church, comes a "Greek priest carrying a light, and guarded by a half a dozen strong men, to secure the first flame for the Russian church." The bright flames of this torch of incarnate superstition contrast ironically with the extinguished candelabrum of truth which Hunt placed upon the frame, and throughout the painting such contrasts prevail. At the center of this Christian ceremony stands the Turkish ruler of the city, and before him is Bim Pasha, his second in command, who calmly leans on his sword, while his troops who are supposed to keep order among the riotous worshippers apparently extort the young inhabitant of Bethlehem. On the left side of the church men carry a "pilgrim personifying 'Jesus Dead.'" while immediately before the Sepulchre, on the left side, stands a pious "Pilgrim personifying the Crucifixion" — both ironic images of the way this superstitious, violent ceremony truly enacts the Crucifixion of their Saviour. From the galleries groups of "ecstatic devotees" look down like a mad chorus upon the events taking place within the church. At the extreme lower right-hand corner, Hunt included his family, depicting his wife as she turns from the turmoil to enfold her children in English Protestant maternal protection.

The Miracle of the Holy Fire is thus Hunt's version of Hogarth's Credulity, Superstition and Fanaticism , which satirizes many of the same excesses within the setting of an English church. In fact, the opening of Trusler's commentary on the plate well captures the spirit of Hunt's painting, and conceivably could have been its inspiration: "Superstition is worse than infidelity. It takes from religion every attraction, every comfort; and the place of humble hope, and patient resignation, is supplied by melancholy, despair, and madness" ( Works of William Hogarth, II, 217). I have found no external evidence that Hunt had either Hogarth's design or Trusler's reading of it in mind when he set out to paint his own satire, but an important similarity between the works of Hunt and Hogarth appears in the fact that both make use of the commonplace satiric device of the observing stranger, and in both cases this standard of sanity is a Turk. As Trusler points out, "The ridicule is wound up by a Turk, who we see through a window smoking his tube of Trinidado; lifting up his eyes with astonishment at the scene, he breathes a grateful ejaculation, and thanks his Maker that he was early initiated into the divine truths of the Koran, is out of the pale of this church, and has his name engraven on the tablets of Mahomet" (II, 218). In Hogarth's print the Turk stands outside the action and looks in through a window, while in Hunt's painting Bim Pasha stands near the center of the action, and yet in his calmness he is as divorced an observer as his Hogarthian predecessor.

Like The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple, which Hunt painted more than three decades earlier, this picture employs many subsidiary actions and emblems to comment upon its main point. Unlike the earlier picture, this one does not have a single commanding visual center. Even this aspect of the painting's composition reflects both its satiric intent and its probable ancestry in Hogarth's graphic works. As Paulson’s Hogarth's Graphic Works reminds us, in a satiric print "people and objects, however alive they are, have to be discrete and relatively static things; they are shown in movement, but caught and held out for contemplation" (I, 55). It is in fact just because he tried to achieve the satirist's emphasis, which requires every part to stand out, that Hunt has created a work which divides into groups of hard, often static figures. Here, perhaps more than in any of his other oils, Hunt succumbed to that Pre-Raphaelite tendency towards the accumulation of disparate, disunified elements for which the critics of the 1860s attacked him.

The painting's lack of a dominant center suggests that Hunt fell prey to the imitative fallacy, creating a chaotic design in an attempt to render a chaotic subject. Even so this singular work is not a failure, since its incredibly crowded, busy picture space has a grotesque energy. Unlike Hogarth, Hunt does not consciously strive for the grotesque by animating the inanimate, but his crowded, jumbled assemblage of people creates much the same effect.

Part of Hunt's difficulty with this painting, and part of the reason it depends so heavily upon its exhibition pamphlet to make its point, is that he was too much of a realist to be a completely effective satirist. In Pre-Raphaelitism and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood he claimed that "whether the celebration is regarded with shame by the advocates of unflinching truth, or with toleration as suitable to the ignorance of the barbaric pilgrims for whom it is retained, or with adoration by those who believe the fire to be miraculous, it has been from early centuries regarded as of singular importance" (II.385). As powerful an emblem of false religion as Hunt believed the rite to be, he was nonetheless attracted to it as an anthropological and ethnographical event, one that must be presented realistically. He further explains in his memoir that he felt "it would be a pity if I, who had seen the wild ceremony of the miracle of the Holy Fire so often, and knew the difference between the accidental episodes which occur, and those which are fundamental, should not take the opportunity of perpetuating for future generations the astounding scene" (II.380-81). His need to present an accurate record of this ancient ceremony required him to place at least some pictorial emphasis upon participants, such as the young monks in the left foreground, who do not function emblematically; and in so doing he distracts us from his satire.

Perhaps this lack of unified intention is one reason why the picture long remained in the artist's hands. In his memoir he only tells us that after exhibiting it first at the New Gallery and then at Liverpool, he "then determined to retain it in my own house as being of a subject understood in its importance only by the few" (II.386). He painted the picture a decade too late for it to have had much effectiveness as a weapon in the war against union with the Greek and Russian Orthodox Churches, even if that quixotic venture had ever had much chance of success. Of course, even without such specific topical reference, The Miracle of the Holy Fire remains satirical, now attacking, not the excesses of this particular rite, but all religion and all conventions which have betrayed their inner spirit. A Pre-Raphaelite to the end, Hunt closed his career as he began it — mocking ossified conventions, beliefs, and practices which smother the life they should nourish.

In observing that a satiric thread runs through Hunt's career, one must be careful not to overemphasize its importance, for such intentions are always joined to other aims as well — to paint more realistically, to teach others to see more clearly, to preach sermons, and, above all, to create powerful, beautiful images of human life. The chief influence of Hogarth, then, is that he provided the much needed example of a painter who had been able to reconcile a realistic style with complex symbolism. Hunt was able to borrow certain methods from the satiric print, and in this, of course, he was paralleled by Robert Martineau, Ford Madox Brown, and others. But Hogarth, whose aims were generally different from those of Hunt, could not furnish all the answers he sought, because the great eighteenth-century artist was primarily a satirist and Hunt was so only on occasion. For all the great admiration Hunt felt for Hogarth, his basic attitude towards his usefulness to his own enterprise is best captured in his remark to Millais before the formation of the Brotherhood: Ruskin had made Tintoretto seem "a sublime Hogarth," a painter who had created a symbolic realism that, unlike Hogarth's, was sublime. Hunt, in other words, wished to find a means of employing methods analogous to those of his predecessor which were yet deeply moving. He wished to create an art employing symbolic realism based on praising God rather than attacking men.

Created 2001; last modified 28 October 2020