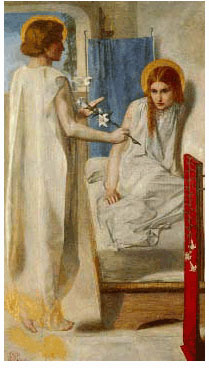

Dante Gabriel Rossetti. The Girlhood of Mary Virgin. 1848–49. Oil on canvas. 32 3/4 x 23 3/4 inches. Tate Britain, London.

These sonnets which Rossetti wrote about other artists" portrayals of the Virgin provide a useful introduction to the two he appended to his first oil painting, The Girlhood of Mary Virgin, for they make us aware of how concerned he was to present her against the background of God's eternal plan to redeem man. The sonnets for his own picture, which were written in 1848, emphasize the fulfilment of prophecy and the completion of that divine scheme in which types play such a significant part. Thus, the first of the two sonnets entitled "Mary's Girlhood" begins: "This is that blessed Mary, pre-elect/God's Virgin," as Rossetti emphasizes that although Mary herself is still unaware of her fate, she was chosen in time long past — or, properly speaking, in a realm outside time — to bring the Saviour into human history. The sonnet next stresses the fact that the event which his picture portrays occurred long ago: "Gone is a great while" since Mary was a girl embodying all virtue, and he thus moves her girlhood into the distant past. After setting the scene in the opening eight lines, the poem moves in the sestet to bring us proleptically to the moment of illumination:

Till, one dawn at home

She woke in her white bed, and had no fear

At all, — yet wept till sunshine, and felt awed:

Because the fulness of the time was come.

Thus, after beginning the poem with a mention of the divine plan, Rossetti builds towards that moment of annunciation — the subject of his second picture — when "the fulness of the time" arrives. This stock phrase associated with types and prophecies again reminds us that although Rossetti was not a believer, his religious works embody a conception of history in which human time is always surrounded by the sacred and is given meaning by it. An examination of Rossetti's major poetry is beyond the scope of this study, but one may point out that even his purely secular verse reveals an attraction to such means of providing coherence to human time. Therefore, he continues to draw upon the language and habits of mind associated with typology in "The Burden of Nineveh," "Troy Town," and The House of Life, even though he ultimately has to admit that love (or the beloved) cannot, like Christ, serve as a center to human history. Thus, although his upbringing in a High Anglican household did not give him a sincere belief in Christianity, it did leave him with a sincere yearning for the order and coherence such belief offered. Many of his poems seek a replacement for that faith, something that will offer continuity for the self, but he fails to find one, and in the closing portions of The House of Life the poet accepts death.

The second sonnet in "Mary's Girlhood," which opens "These are the symbols," functions largely as a programmatic guide to the picture's iconography, but even it emphasizes that the painting presents a significant moment, a moment which we perceive occurs not long before the Annunciation:

Until the end be full, the Holy One

Abides without. She soon shall have achieved

Her perfect purity: yea, God the Lord

Shall soon vouchsafe His Son to be her Son.

Turning to the picture itself, we observe that although Rossetti has made a rather self-conscious use of traditional religious iconography, few of its elements function typologically and none in the manner of Collins, Millais, and Hunt. In fact, even with his own painting Rossetti proceeds as he had with the works of others, depending upon his sonnets to provide the necessary temporal and symbolic context. He uses a trellis, curtain, and balcony railing to create what is the first Pre-Raphaelite work using the characteristic "window composition," and within his enclosed space he depicts St. Anne assisting Mary to embroider the cloth we find completed in The Annunciation. "On that cloth of red," the sonnet instructs us,

I' the centre is the Tripoint: perfect each,

Except the second of its points, to teach

That Christ is not yet born.

Before the two women stands a pile of massive volumes, each emblematic of a spiritual virtue,

whose head

Is golden Charity, as Paul hath said —

Those virtues are wherein the soul is rich:

Therefore on them the lily standeth, which

Is Innocence, being interpreted.

Near Mary's feet are the "seven-thorn"d briar and the palm seven-leaved . . . her great sorrow and her great reward," two iconographical elements which can be taken either as standard attributes functioning allegorically or as prefigurative images. But even if they are understood to be types — of Mary's sorrows and Christ's Passion — the briar and palm do not occur as natural, realistic elements of the scene. Rather they are placed there by the artist as emblems, so that Rossetti has created a not very successful mixture of a realistically conceived event and an added on symbolism — precisely the thing he avoided in The Passover in the Holy Family. The vase with the vine growing in it, the lantern, and the dove are all traditional components of the annunciation theme, and while it is certain that the resting dove is meant to be "the Holy One/ [Who] Abides without," it is not clear if Rossetti understood the other elements, which he does not interpret. At any rate, all these elements serve to create what is properly termed a "pre-Annunciation," a picture in which all is readied for that great event. Despite the obvious clumsiness of the poem's assertion that Mary has not yet "achieved/Her perfect purity," it does serve Rossetti's purpose quite well: elucidating the picture's iconography, it endows a domestic scene with a greater significance and enables us to understand that Mary dwells in a sacred space and time. Nonetheless, the picture's iconography is not entirely successful, and unlike the later works of his friends it does not employ typology for a sacred realism. Rather it uses conceptions of time and history associated with this symbolic mode in the poems which accompany The Girlhood of Mary Virgin.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Ecce Ancilla Domini (The Annunciation). 1849. Oil on canvas, 28 l/2 x 16 l/2 in. Tate Gallery, London.

The Annunciation, a far more daring picture, uses some of the conventional images associated with this theme, such as the dove, lily, and extinguished candle, but it largely abandons any emphasis upon iconography, relying instead upon its emotional intensity. Despite obvious problems with perspective, Rossetti's Annunciation succeeds in presenting a convincing interpretation of the way the human meets the divine: Mary's angst, her withdrawal into herself, provides a believable and fitting culmination of the events depicted in The Girlhood of Mary Virgin. The Annunciation does not seem quite in accord with the earlier sonnet, which relates that Mary "had no fear/At all," for her expression seems more than one of awe. But this sonnet does, once again, provide the typological context for the painting. Not until 1856, when he created The Passover in the Holy Family, was Rossetti able to integrate types within the picture itself.

Created 2001 last modified 31 October 2020