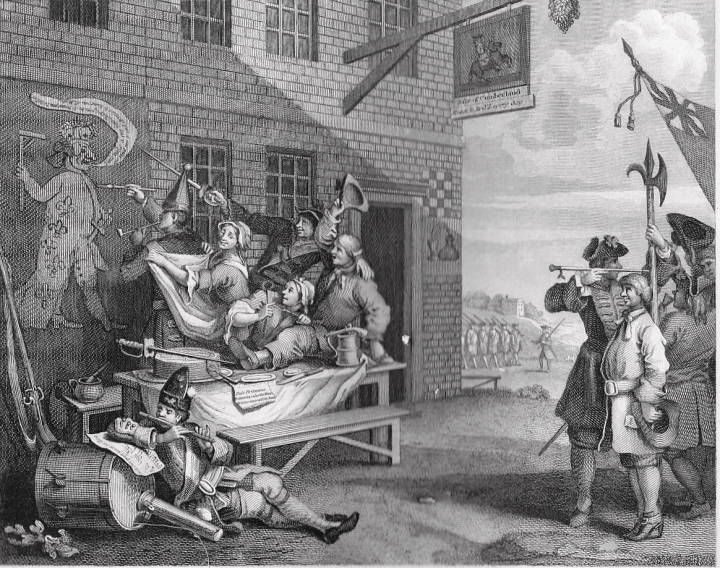

At the same time that we perceive the importance of this visionary work to Hunt's career, we must also note that he had already been moving towards this form of integrated symbolism in several of his earlier works. Even before the religious experience that enabled him to paint The Light of the World , he had made several attempts to combine realism and symbolism under the influence of William Hogarth, who was important to the entire circle of the Brotherhood and its associates. Hogarth was not only a moralist who believed that England had to establish her own form of art but he was also one of those chiefly responsible for the fact that England had "wrested" glory "from the maws of ignorance, indifference, and shallow self-confidence" (II.482). although he was only an ordinary member of the Pre-Raphaelite pantheon and did not even have a star next to his name (I.159), he was the kind of artist who could well serve as a hero for Hunt and his friends. In particular, he exemplified the admirably courageous individualist who had made his way despite the attacks of critics and connoisseurs. Hunt, who agreed with the views the great satirist had presented in Gate to Calais: The Roast Beef of Old England, also shared his predecessor's love-hate relationship with his country: like Hogarth, he took the fiercest pride in his England while yet recognizing that she fell far short of his ideal.

Left: England. Right: France by Hogarth. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Both artists were also resolutely middle class and blamed the aristocracy and the wealthy for the nation's moral and artistic shortcomings. Both, moreover, believed that the English Church, which did not support the arts, was a chief cause of the sad state of painting; and both thought the aristocracy's influence in the Church was in part responsible for this state of affairs. As Hunt pointed out in the 1897 Contemporary Review, "the sham art that we have got in our churches has been tolerated so long because art is considered to be properly an indulgence for the rich" (50-51). Whereas Sir Joshua Reynolds had sought to make the artist a member of the aristocracy, Hogarth wished him to be a staunch member of the middle classes, and so did Hunt (See Paulson, I, 16). Both men, in fact, were hard-headed businessmen who had made their way against great odds. In addition, Hunt, like Hogarth, depended for financial success upon a middle class audience: he, like his predecessor, relied upon engravings sold to a wide public rather than upon the support of a few wealthy patrons, and he often earned more from reproductions of his work than from the originals themselves.

Strictly speaking, Hunt divided the price of his major oils into the cost of the picture and a fee for copyright, but it seems fair to say that Gambart and the other dealers who purchased his major works paid such high prices only because they also had the copyright which permitted them to sell engraved reproductions. The central importance to his career of this means of reproduction partially appears in the fact that he returned ahead of schedule from the Middle East while at work on The Triumph of the Innocents because Agnew requested him to do the final work on a plate. See ALS to Tupper, 8 May 1878; London (Huntington MS.). Jeremy Maas's Gambart, Prince of the Victorian Art World narrates in valuable detail the dealer's relations with Hunt.

Hogarth was also particularly important to Hunt because he expanded traditional notions of serious painting. Ronald Paulson explains that "Hogarth attempted . . . to argue that his "modern moral Subjects" were not contemptible caricatures but a new genre: "writers never mention," he complains in the Notes, "in the historical way of an intermediate species of subjects for painting between the sublime and the grotesque" (Hogarth's Graphic Works, I, 12).

Furthermore, he made a break with the traditions of history painting when he invented his own subjects, something which Hunt did within the narrower context of religious art. It is not that he modelled himself after Hogarth in these matters, but that he could look to him as an example of a pioneering artist who had convinced the public that an art suited to new times had to employ new themes and methods.

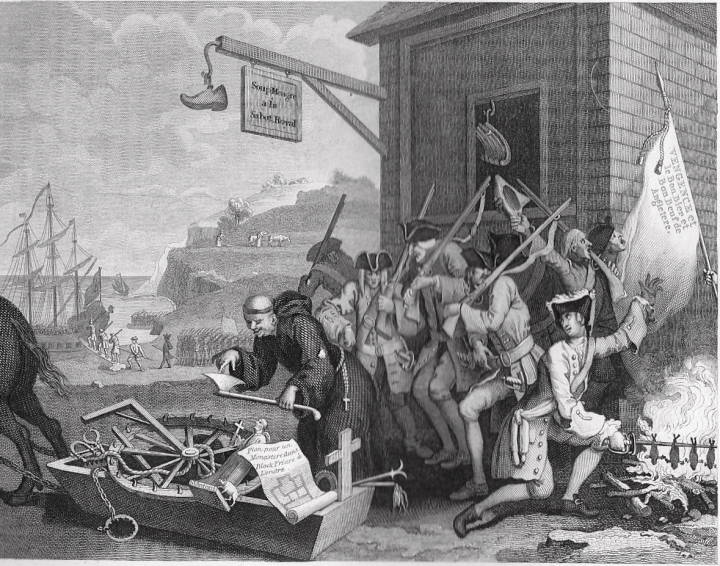

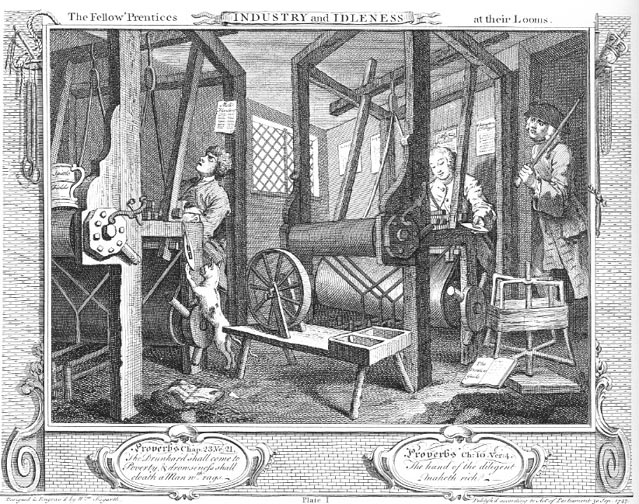

An example of Hogarth’s texts on the frame and within the picture space, which became a model for Hunt. The Fellow Apprentices at their Looms from Industry and Idleness, I. William Hogarth (1697-1764). 1747. 10 3/16 x 13 3/8 inches.

In addition to Hogarth's importance as a pioneer and moralist, he offered two ways of solving the problems with which Hunt was concerned: he successfully combined realism with elaborate iconography, and he used language to clarify the meaning of his images. From Hogarth, Hunt (and Ford Madox Brown) learned to employ documents, labels, and inscriptions within and without the picture to intensify the effect of their visual images. Furthermore, the nineteenth-century editions of Hogarth's engravings which boasted elaborate commentaries seem to be an important source of Hunt's own use of explanatory manifestoes, just as they seem to provide one source for Ruskin's detailed moral explications of art, for they are a comparatively rare example of close readings of art available at mid-century. Hunt and other members of the Pre-Raphaelite circle would most likely have encountered Hogarth's work in editions containing commentary by the versatile Rev. John Trusler, who published an abridgement of Blackstone's Commentaries, popular histories, sermons, books on etiquette, gardening guides, and the very popular Way to be Rich and Respectable. He first issued his Hogarthian commentaries in 1768, and the British Museum Catalogue, which has an incomplete listing of these commentaries, records editions of 1821, 1831, 1833, 1861, and 1891 who turned the satiric plates into full-fledged sermons. Although modern students of Hogarth have little good to say for such "Truslerizing," Hunt almost certainly became acquainted with the satires in this form and hence encountered what we may term a Victorianized Hogarth.

Related Materials [not in print version]: Parallels Between Hogarth and the PRB

Comparing Hogarth's series, Industry and Idleness, Marriage à la Mode, or the Rake's and Harlot's Progress, to the works of Holman Hunt, other members of Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, and their associates reveals the following parallels:

Strong narrative emphasis (e.g., Industry and Idleness — Hunt's Awakening Conscience)

Signifying visual elements on frame (e.g., Industry and Idleness's emblems of power and punishment — Hunt's Awakening Conscience)

Signifying verbal elements on frame (e.g., Industry and Idleness's scriptural quotations — Hunt's Awakening Conscience)

Satirical attacks on aristocracy (e.g., Marriage à la Mode — Hunt's Awakening Conscience)

Middle-class anti-aristocratic emphasis upon work as ennobling (e.g., Industry and Idleness — Hunt's Shadow of Death; Brown's Work)

Symbolic animals act as foils to main action (e.g., Marriage à la Mode (1); Industry and Idleness (1) — Hunt's Awakening Conscience)

Original painted image disseminated as engraving: (e.g., Marriage à la Mode — Hunt's Awakening Conscience, Finding, Shadow of Death)

Patrons: Muliple middle-class purchasers rather than a single Aristocrat — Hunt's Awakening Conscience, Finding, Shadow of Death

Grotesque and often ugly elments Industry and Idleness-- rejection of Neoclassical ideal of beauty — Hunt's Awakening Conscience; Millais's Christ in the House of His Parents

Seriation: Organizing works in narrative series — Millais and Hunt's Isabellas; Egg's Past and Present; Burne-Jones Perseus, Pygmalion, and Briarose Series

Arranging works in pairs (e.g., Industry and Idleness and Gin Lane and Beer Street — Hunt's Light of the World and Awakening Conscience; Egg's Life and Death of Buckingham)

Isabella and the Pot of Basil by William Holman Hunt. 1867, Oil on canvas. 23 7/8 x 15 1/4 inches (60.7 x 38.7 cm.). Signed with monogram and dated lower left. Lent by the Delaware Art Museum (ace. no. 47-9) Special Purchase Fund.

The most curious parallel between Hunt and Hogarth is that when they became angered by charges that they could not paint true beauty, they both tried to win public approval with similar works specifically created to prove the critics wrong; and both, failed. Hogarth's Sigismunda with the Heart of her Husband is not only an obvious predecessor to Hunt's Isabella and the Pot of Basil, but both derive from Boccaccio's Decameron, Hogarth's by way of Dryden and Hunt's by way of Keats. These paintings' harsh reception was particularly painful to both artists, since they had made use of deeply personal experiences in painting them. For the figure of Sigismunda, Hogarth had drawn upon memories of his wife weeping over her dead mother, and Hunt's wife Fanny, who died before the picture was completed, had modelled for Isabella; even though the face of this figure was not hers, Hunt was deeply hurt by charges that his Isabella looked like a fishwife.

Created 2001; last modified 27 October 2020