Unless otherwise noted, the photographs here were taken by the author during her visit to the exhibition. Please click on them for more details and larger versions. Please check with the gallery if you wish to reproduce them, and, if you do so, please attribute the photographer and the Victorian Web, and link to the review.

Banner for the exhibition, on the railings outside the gallery (partial view).

"I had a letter from Rossetti Thursday saying that Ruskin had bought all Miss Siddall's ... drawings and said they beat Rossetti's own," wrote Ford Madox Brown in his diary on 10 March 1855. "This is like R, the incarnation of exaggeration, however he is right to admire them. She is a stunner and no mistake" (qtd. in Moyle 175). Here, Brown pokes fun at Ruskin's enthusiasm, but agrees with his verdict on Elizabeth Siddal's work: his closing comment encompasses her artistic talent as well as her looks. In the current exhibition, "Pre-Raphaelite Sisters" at the National Portrait Gallery, London (17 October 2019 – 26 January 2020), curator Jan Marsh sets out to persuade us that the women associated with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, their models, mistresses and wives, the helpers on whom they depended in a myriad other ways, were also partners in their professional endeavours.

The Pr-Raphaelite Brotherhood and their associates (partial view), relegated to an intermediate space here.

Consigning the familiar faces of the Brotherhood to a series of greyscale posters in a linking room, Marsh gives the women pride of place instead, interspersing the mostly well-known paintings of them with less familiar work — works that they produced themselves. Of course, not all had artistic aspirations. In several instances, their lives and struggles are the chief interest. Allotting a separate space to each of the women in turn, Marsh brings out their characters, and their relationships with the artists and others, sympathetically. One of the poster-girls for the exhibition, for instance, is Annie Miller, as seen in William Holman Hunt's Il Dolce Far Niente (1866). Inside the gallery, the exhibition label next to the painting itself says that Annie looks contented, comfortable in her "enclosed space." But was she? The reflection in the little van-Eyckian mirror behind her reveals that she is gazing into a fire; to the observer, however, she seems to lean out, away from her confines. The label continues, "Hunt criticised Miller's alleged liking for leisure." This is true: finding her both frivolous and wilful, not to mention deceitful, he broke off his engagement to her. But Annie Miller was lucky. She moved on, married an officer, had a family and lived to a ripe old age. Sometimes it pays to be wilful.

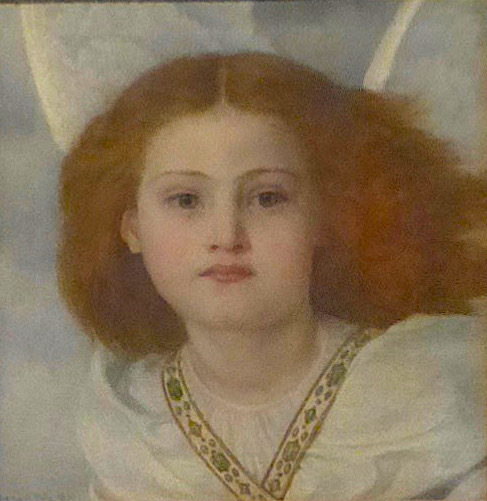

Albert Moore's Mother of Sisera (1866).

Another strong character among the Pre-Raphaelite muses was Fanny Eaton. Of Jamaican origin, with dark skin and distinctly exotic looks, she was a perfect godsend to the Brotherhood, and one of the most touching works in the exhibition is Albert Moore's painting of her as the Mother of Sisera, looking anxiously for the son who would never return. No matter that Sisera in the Old Testament was an oppressor hated by many, Moore shows that her feelings were those of any mother in her position. Fanny brought up a large family on her own in difficult circumstances; hers was clearly not an easy life. Yet she lived even longer than Annie Miller, leaving a lasting legacy through her modelling — which, in itself, was an important contribution to the movement.

As regards longevity, others were often less fortunate. Elizabeth Siddal's fate is well known. Her submission to the torture of lying in poorly heated water in a tin bath, to model for Millais's Ophelia (1852), seems to have marked the first stage of her decline into ill-health and early death. The gallery label next to a small replica of it here suggests that it also marked her "commitment to artistic practice." True, she had first entered the artistic milieu through her skill in drawing, and Marsh shows her not only as Ophelia, but as Viola/Cesario in Walter Howell Deverell's large canvas, Twelfth Night Act II, Scene IV (1850) — her first modelling assignment. Siddal also sat for Rossetti, of course, whom she married in 1860, and he sketched her at her easel, drawing him — a neat inversion of the roles we usually ascribe to them. And, yes, her own drawings have a distinct character — angular, often tentative, naïve, and touching. But surely Ruskin's rapturous response to them was over-heated.

Fanny Cornforth, in The Blue Bower by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1856).

Speaking more of her contribution to the Brotherhood are the curled strands of Lizzie's auburn hair, which are also on display — the very hair that Rossetti loved to paint, its colour undimmed. This is one of several poignant personal mementos here that remind us of the realities behind many of these beautiful paintings, the intimate relationships that developed between artists and models, and the emotional costs of these relationships to the "sisters" involved, whether models or wives (or both). Jan Marsh's emphasis is not on exploitation, which would, after all, rob the "sisterhood" of agency. But there are occasions, for example when confronted with the record of Fanny Cornforth's admission to the Sussex County Asylum, when we are bound to reflect on the vulnerability of the working-class model. How sad that the vibrant young woman who sat for Burne-Jones as well as Rossetti, and whom we see here in works like Rossetti's The Blue Bower (1856), should have come to such a pass.

In other cases, however, the women's own artistic gifts were so impressive, so truly "stunning," that they are now being properly recognised. It helped, of course, that these women were higher up the social scale, and moved in artistic circles. Maria Zambaco, Burne-Jones's temptress in paintings like The Beguiling of Merlin (1874), as she had been in real life, had studied not only at the Slade, but under Rodin in Paris. Four of her finely detailed medallion portraits are on display here. She was clearly a first-rate medallist. Another who contributed a woman's vision to the movement was her relative in the wealthy Anglo-Greek community in London, Marie Spartali Stillman. Stillman's painting, The First Meeting of Petrarch and Laura (1889), is exhibited here for the first time, but she has already had an exhibition devoted to her in America, at the Delaware Art Museum, 2015-16 — and after that at our own Watts Gallery, Compton. And few will go quickly past Joanna Boyce Wells's radiant Thou Bird of God (1861), shown here after an interval of twenty-five years. This painting, together with her portrait of Fanny Eaton, more than justifies her claim, unmissably and memorably printed on the wall, to "have talents or a talent."

Left to right: (a) Maria Zambaco's head of Marie Stillman, 1886. (b) Marie Spartali Stillman's The First Meeting of Petrarch and Laura (1889) (c) Joanna Boyce Wells's Thou Bird of God (1861).

The best-known artist among the "sisters" is probably Evelyn De Morgan, whose splendid Night and Sleep (1878) has travelled up from the Watts Gallery to hold its own, quite triumphantly, by the two large Burne-Jones canvases on the far wall. What a treat to see these works gathered together — and how well they support Marsh's argument that we should remember these women's contributions to Pre-Raphaelitism.

Elsewhere, in other members of the "sisterhood," there are hints of undeveloped, probably frustrated creativity. There is the slight but accomplished watercolour, Garden Path with Rose Walk (undated), attributed to the young Effie Ruskin, for instance, and — a surprise for many, perhaps — evidence of Georgiana Burne-Jones's artistic skill too. Burne-Jones's portrait of her, of 1883, with their children Philip and Margaret glimpsed in a further room, assumes new significance in this context. In this painting, Philip, described in the gallery note as already being a "professional painter," is seated at an easel, with Margaret (supportive rather than active) standing behind his chair looking on. Georgiana herself, the main figure, holds a beautifully illustrated herbal. Her own interest was in illustrative work, small-scale, exquisite drawing and etching, of the kind displayed here by a recent discovery — her moving illustration of Thomas Hood's poem, The Bridge of Sighs, in which people gather round the body of a poor homeless woman, just pulled out of the Thames. But Georgiana's life, like that of most Victorian wives, was largely centred on her husband's, which in this case meant her husband's art rather than her own.

The social context cannot, and should not, be left out of the sisterhood's story. These women were not a sisterhood in the sense that the men were a brotherhood. Their contributions varied betwen lending their looks and inspiration to the movement, and offering their artistic visions. Their fates diverged too. What they had in common — despite the men's own, sometimes misguided, efforts to overcome it — was the gender prejudice of the times. The working-class model, looked on with suspicion when not being celebrated for her beeauty, faded from view; her better-off sister, however talented, had problems too. Even Joanna Wells had added, in the quotation given on the gallery wall, that she had "the constant impulse to employ" her gifts, and a "longing to work," as if this outlet was often denied her, as no doubt it was. When she died in 1861 following the birth of a third child (her face movingly portrayed in a postmortem portrait by Rossetti), she had surely not fulfilled one quarter of her potential.

Left: Evening bag embroidered by Jane Morris, c.1878. Bequeathed by May Morris. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London (image courtesy of the V&A). Right: Embroidered Shoes by Marie Spartali Stillman. Delaware Art Museum, Gift of Eugenia Diehl Pell, 2016.

One acceptable form of "women's art," at every social level, was embroidery, and Jane Morris's evening bag, and the evening shoes embroidered by Marie Spartali Stillman, show the level of artistry that could be attained in this medium. When not engaged in modelling or with wifely duties, this could be an alternative to the fine arts, and indeed cross the increasingly porous boundary between the fine and applied arts, as the contribution of embroidery Arts and Crafts Movement proved. It could also be an agreeably sociable form of artistic expression: Stillman often visited Jane Morris at Kelmscott Manor, and she pays quiet tribute to those visits in her wildflower design here.

For obvious reasons, the works that dominate these rooms are still mainly those painted of, rather than by, the women in the Pre-Raphaelite circle. This is not a criticism. Far from it. Simply to see them together justifies the title of the exhibition. The fact is, that without these faces, these features, these remarkable presences, the Brotherhood's art would not have been what it was. Fanny Eaton, in particular, is likely to attract wide attention now, as our long-neglected black history comes into prominence. As for those "sisters" who did leave a body of work themselves, like Christina Rossetti, some have already received recognition. Only last winter, a wonderful exhibition of Christina Rossetti's work — mainly as poet, but also as model and inspiration — was held at the Watts Gallery. Others are now emerging more fully into the public gaze. But even in such cases, there is much to be learned: for example, Christina Rossetti's sonnet on Siddal, "In an Artist’s Studio," is another of the items here that has never before been put on public display.

In her writings, Marsh has been promoting the Pre-Raphaelite "sisters" for a long time now. This current project, in which she was supported by the National Portrait Gallery's chief curator Alison Smith, really clinches her argument about their importance. She has made it abundantly clear that the "stunners," in particular, contributed much more than we ever realised to a movement usually considered, from its very title, to be predominantly male. This gives us a fresh, more balanced perspective on a particularly attractive part of our shared cultural heritage.

Related Material

- Review of "Christina Rossetti: Vision and Verse" at the Watts Gallery, Compton, 13 November 2018 - 17 March 2019

- Review of "Uncommon Power": Catherine and Lucy Madox-Brown at the Watts Gallery, Compton, 28 September 2021 - 20 February 2022

- The Lady of Shalott: Pre-Raphaelite Attitudes Toward Woman in Society

- Circe and Other Sorceresses

Bibliography

Moyle, Franny. Desperate Romantics: The Private Lives of the Pre-Raphaelites. Pbk ed. London: John Murray, 2009.

Created 28 October 2019