Introduction

he formation of sketching clubs, whose purpose was for members to help each other by criticising each other’s work, was common during Victorian times. As Colin Cruise has pointed out they "had a practical purpose rather than a radical or reforming one: they offered professional support and friendly advice or criticism from within the artist’s peer group, and helped in sharing the costs of hiring models, even providing models from within the group. They augmented rather than challenged the Royal Academy and its schools, and asserted their differences from the prevailing orthodoxies in a variety of ways, often more startling than substantial, such as smoking pipes and drinking quantities of ale, growing their hair long and wearing unusual clothes" (40). A well known such example would be the popular Langham Sketching Club, which was the oldest working art society in London having been founded in 1830. On a Friday afternoon Langham Sketching Club members were given one or two subjects that had been previously decided upon the previous evening to make sketches of within a limited time period. Sketches could be made in various media upon paper or on oil on canvas. During the mid-Victorian period many progressive young artists belonged to this society including Charles Keene, John Tenniel, Carl Haag, Fred Walker, George John Pinwell, Paul Falconer Poole, Edward Poynter, Henry Stacey Marks, Frederick Smallfield, J. D. Watson, Arthur Rackham, Frank Dicksee, Henry Moore, John Anster Fitzgerald, and Philip Calderon.

Young art students also routinely used such sketching clubs as a means of self-education to supplement the training they received at the Royal Academy Schools. One well-known example was the informal Sketching Club formed by Henry Holiday, Simeon Solomon, and Marcus Stone during their student days. It was later to include Albert Moore, and possibly Fred Walker, William Blake Richmond, as well as others. The club met once a week at their respective houses in rotation, where the host would suggest the subject for the evening's work.

It is therefore not surprising that several sketching groups were formed that included members of the circle that formed around the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.

The Cyclographic Society (The Cyclographic Club)

illais claimed that Walter Deverell, Richard Burchett, his friend and fellow teacher at the Government School of Design, and Nathaniel Everett Green founded the Cyclographic Society (65). Dante Gabriel Rossetti, however, claimed he and Walter Deverell founded the club (Fredeman, Correspondence, letter 48.1, 55). It was active at least between March and September of 1848, just before the official formation of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. The formation of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in October 1848, and the defection of those members, led to the demise of the Cyclographic Society. As William Holman Hunt noted, "the general level of the contributions, which could not be considered high in character; indeed the Club was already in danger of splitting up, owing to the glaring incompetence of about three-quarters of its members, and the too unrestrained ridicule of the remainder" (103). All the future members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood belonged, with the exception of William Michael Rossetti, but it also included artists that did not become part of the Pre-Raphaelite circle. Others of the fifteen known members, many of whom are virtually unknown today, included John Hancock, J. T. Clifton [likely John S. Clifton], William Dennis, T. W. Watkins, John Alfred Vinter, and J. B. Keene. Some like Vinter had been fellow students of the P.R.B. at the Royal Academy Schools. Of the members only Deverell and Hancock were to become close associates of the P.R.B. Alexander Munro had been proposed as a member but it is uncertain whether he ever joined.

All members were expected to contribute drawings and sketches to a portfolio about once a month, which would then be circulated to the other members for their comments and criticisms. Sometimes there were set subjects, such as the suggestion by Rossetti for a series of drawings on John Keats’s “Isabella”. Members were to write their criticisms on a Criticism Sheet. The Society meetings were stimulating and companionable. Some members apparently experienced facetiousness in their criticisms despite the fact that within the rules of the club was the following admonition: "The members of the C.S. are requested to write their remarks in Ink, concisely and legibly, avoiding SATIRE or RIDICULE, which ever defeat the true end of criticism, and are more likely to produce unkindly feeling and dissension" (Fredeman, P.R.B. Journal, 108-09). From the criticism sheets that survive it appears the members in general took the task seriously. (Fredeman, P.R.B. Journal, 109-12). Criticisms were taken out by the artist, along with his drawing, when the portfolio came back for a further contribution. Meetings were to be held every Saturday but attendance was sporadic at best. William Holman Hunt did not recall ever attending a meeting. The club was not without its problems, however. In a letter from D. G. Rossetti to his brother William Michael from August 30, 1848 he writes: "The Cyclographic gets on fast. From discontent it has already reached conspiracy. There will soon be a blow-up somewhere" (Fredeman, Correspondence, letter 48.10, 71).

The earliest known surviving drawing contributed to the Cyclographic Society is a study by Hunt for The Pilgrim’s Return from Keats’s “Hyperion.” Hunt’s other designs included Peace and War from Leigh Hunt’s “Captain Sword and Captain Pen,” One Step to the Death Bed from Shelley’s “Ginevra,” and Lorenzo at his Desk in the Warehouse from Keats’s “Isabella.”

Two Drawings by Hunt: Left: The Pilgrim's Return. 1847. Graphite on paper, 5 ½ x 7 ½ inches (14 x 19.1 cm). Pencil on paper. Private collection. Right: Lorenzo at his Desk in the Warehouse. 1848-50. Pen and grey ink on paper, 8 ¾ x 13 ⅛ inches (22.2 x 33.3 cm). Collection of the Louvre Museum, Paris, accession no. RF 39617. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

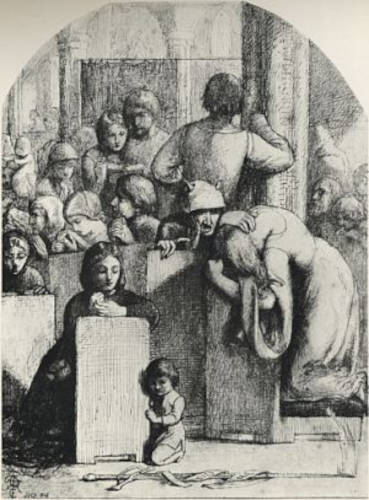

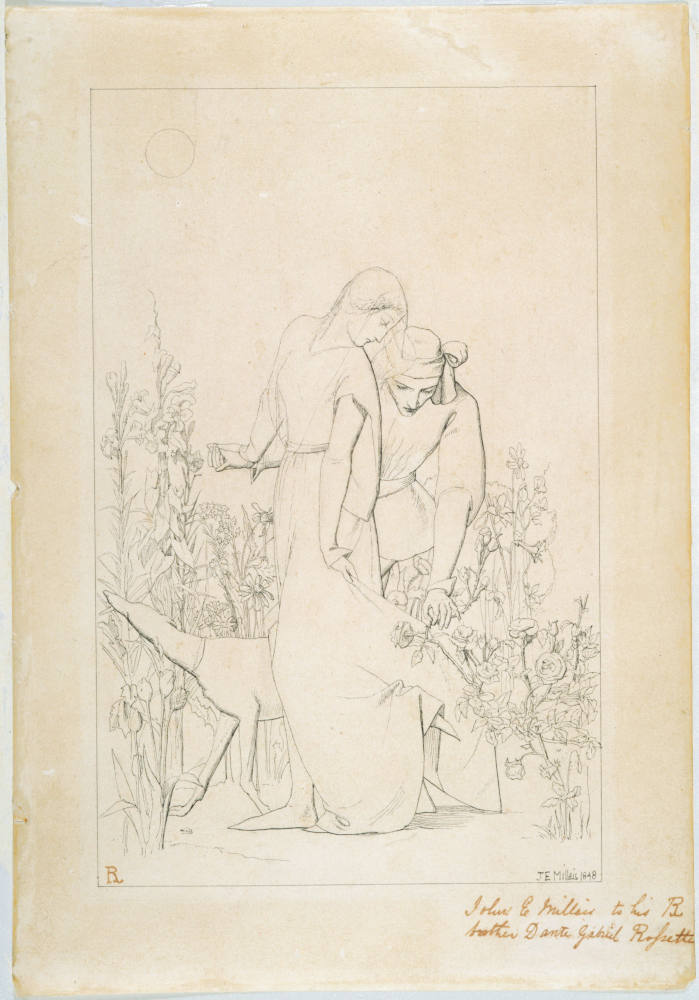

Rossetti is known to have submitted at least three of his drawings for criticism – La Belle Dame Sans Merci from Keats, Gretchen and Mephistopheles in Church from Goethe’s Faust, and Genevieve from Coleridge’s “Love.” Millais’s contributions likely included his initial design for Ferdinand Lured by Ariel from Shakespeare’s The Tempest, Lovers by a Rosebush, and Lorenzo and Isabella from Keats’s “Isabella.”

Left: Genevieve by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882). Signed with monogram and dated “August 1848.” Pen and ink on paper, 10 ¾ x 5 ½ inches (27.3 x 14 cm). Collection of the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, accession no. 748. Middle: Gretchen and Mephistopheles in the Church by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882). Pen and ink on paper, upper corners rounded, 10 ¾ x 8 ⅛ inches (27.3 X 20.7 cm). Private collection. Right: Lovers by a Rosebush by Sir John Everett Millais Bt PRA (1829-96). 1848. Pen and ink on paper. 10 x 6 ½ inches (25.4 x 16.5 cm). Collection of the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, accession no. 1920P12

Left: Ferdinand lured by Ariel. Sir John Everett Millais Bt PRA (1829-96). 1848. Pen and ink on paper, 11¼ x 7¾ inches (28.4 x 20.0 cm). Collection of Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, accession no. 10364. Right: Study for Lorenzo and Isabella by Millais. 1848. Pen and India ink on paper, 7 15/16 x 11 ½ inches (20.1 x 29.2 cm). Collection of the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, accession no. 1396.

James Collinson’s one known contribution was The Novitiate to a Nunnery, now untraced. Many of the drawings for the Cyclographic Society were a revival and modification of the "outline style" that went back to John Flaxman but was later adopted by German illustrators like Retzsch and Rethel. In Cruise’s opinion the lasting legacy of the Cyclographic Society was that it "encouraged imagination over academic skill. It was important in setting its members subjects derived from literature that invited small-scale compositions where the emphasis was on individual interpretation. These were key factors in the more ambitious works just about to be undertaken by the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, which were to distance them further from the Royal Academy, its training methods and the expectations of its annual exhibitions" (41).

The Folio Sketching Club

he Folio Sketching Club was founded in 1854, primarily at the instigation of Millais. As compared to the Cyclographic Society it primarily consisted of members of the Pre-Raphaelite circle and it was intended to be more ambitious. It also included a larger number of artists and admitted women members. Its founding is discussed in a letter of February 24, 1854 from D. G. Rossetti to William Bell Scott:

I write this very short note to tell you of a project started tonight at Millais’s, & which I engaged to communicate to you & one or two others immediately: viz: a sketching club to be called The Folio. The plan as follows in the rough – a folio to be sent around to all members in rotation, and each to put in a drawing whenever it reaches him, taking his former one out. The drawings all to be made in pen & ink, of any subject (i.e. design). Eighteen members have been named conjecturally, as opposite, the majority of course to be got by Millais. It must be a matter for consideration as to whether members residing in the country can possibly receive the folio regularly – but in any case we hope you will join, which can be done by sending a drawing always by a certain date…Might it not be a first rate thing?" (Fredeman, Correspondences, letter 54.15, 322).

Artists initially suggested for membership included Rossetti, Hunt, Millais, Madox Brown, Charles Allston Collins, Hughes, Michael Frederick Halliday, Munro, John William Inchbold, Mark Anthony, John Leech, Dicky Doyle, John Mulcaster Carrick, and Josef Wolf. Two women artists were initially included, Lady Waterford (Louisa Anne Beresford) and her cousin the Hon. Eleanor Vere Boyle. William Michael Rossetti was appointed secretary and drew up the rules for the club.

The Pardoner’s Tale of Dethe and the Riotours by Frederic George Stephens (1827–1907). c. 1854. 1852. Pen and black ink on paper, 115/8 x 171/2 inches (29.5 x 44.6 cm). Collection of Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, accession no. WA1977.106.

Later Frederic George Stephens, Anna Mary Howitt, and Barbara Leigh-Smith were invited to join. It appears most people who were invited accepted and only Madox Brown is known to have resisted all persuasion and declined. As Millais remarked "What a peevish old chap he is!" (66). Hunt did not contribute as he was away on his first trip to the Holy Land during the time The Folio was in existence. Perhaps the most surprising inclusion is Wolf, a German-born artist who had moved to London to work at the British Museum in 1848. He was an illustrator and an exceptional painter of animals and birds. He was also later invited to exhibit at the first Pre-Raphaelite group exhibition held at 4 Russell Place in 1857.

Despite the initial enthusiasm for the project The Folio was slow to get underway. This was at least partly due to the fact Millais was distracted by his relationship with Effie Millais who was then publically suing her husband John for an annulment on grounds of non-consummation. Millais had by this time, however, already purchased a leather portfolio to transport the drawings. J. G. Millais, quoting Hughes, writes: "Millais, who was the only man amongst us who had any money, provided a nice green portfolio with a lock in which to keep the drawings" (65). William Michael Rossetti, in a letter of May 30, 1854 to Scott, notes: "Perhaps you have been wondering what has become of ‘The Folio.’ I can scarcely tell you. The rules were enacted, the paraphernalia bought; but things have come to a deadlock in the hands of Millais. He kept the folio I know not how long, and is now gone to Scotland; possibly he has passed it on to Gabriel, who is not yet back from Hastings, or to someone else" (Peattie, Letters , 50). The scheme did eventually progress but exactly which drawings were circulated is not as well documented as for the Cyclographic Society. Four works, including drawings by Millais, Stephens, A. M. Howitt, and Smith, are known to have circulated as far as Rossetti by the beginning of August 1854.

Left: Sketch for The Romans Leaving Britain by Sir John Everett Millais Bt PRA (1829-96). 1853. Pen and brown ink and wash on paper, dimensions unknown. Location unknown. Right: Study for Found by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882). Signed with monogram and dated “1853.” Pen and brown ink and wash on paper, 8 1/16 x 7 ⅛ inches (20.5 x 18.1 cm). Collection of the British Museum, accession no. 1910,1210.1

In July the theme chosen for the drawings was “Desolation.” Millais contribution was a pen and ink sketch of The Romans leaving Britain that focused on a Roman soldier leaving a British girl absolutely devastated at his departure, both of them knowing he will never return. Howitt submitted a preliminary study for a painting to be called The Castaway showing what Rossetti described as "a dejected female, mud with lilies lying in it, a dust heap & other details, and symbolical of something improper" (Fredeman, Correspondence, letter 54.57, 369) The motto of this drawing was adapted from Job 30:19: "He cast me into the mire, and I became dust and ashes" (Hirsh, Bodichon, 49). Smith’s contribution was a glen scene of a wild and desolate landscape called Quarry by the Sea . Rossetti’s sketch for this theme was an early study for Found, showing a prostitute being discovered at dawn by her former sweetheart as he brings a calf to market. Rossetti had considered submitting his drawing of Hamlet’s Rejection of Ophelia instead, but feared he could not get it done in time to restart the circulation of The Folio quickly enough. In fact Rossetti did not complete this drawing until 1858 so it was never included in his Folio contributions. The drawing by Stephens was his study from Chaucer’s The Pardoner’s Tale of Dethe [Death] and the Riotours.

For whatever the reasons The Folio club unfortunately did not persist long, although the exact circumstances of its demise are unknown. Rossetti last mentions it in a letter to William Allingham of September 19, 1854. The usual reason given is Rossetti’s dilatoriness in passing the folio on to other members.

Links to Related Material

- Works Created at the Sketching Clubs Associated with Artists of the Pre-Raphaelite Circle/a>

- The First Pre-Raphaelite Group Exhibition

- The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherthood

- The Hogarth Club

Bibliography

Cruise, Colin. Pre-Raphaelite Drawing . London: Thames & Hudson, 2011.

Fredeman, William E. The P.R.B. Journal. William Michael Rossetti’s Diary of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood 1849-1853 . Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1975, Appendix 3, 108-12.

Grieve, Alastair. “Style and Content in Pre-Raphaelite Drawings 1848-50.” Pre-Raphaelite Papers . Ed. Leslie Parris. London: The Tate Gallery, 1984.

Hirsch, Pam. Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon: Feminist, Artist and Rebel . London: Chatto & Windus, 1998.

Hunt, William Holman. Pre-Raphaelitism and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. 2 vols. London: Macmillan and Co. 1905.

Marsh, Jan: Dante Gabriel Rossetti Painter and Poet. London: Weidenfeld & Nicholson, 1999.

Millais, John Guille. The Life and Letters of Sir John Everett Millais. 2 vols. New York: Frederick A. Stokes Co., 1899.

Prettejohn, Elizabeth. The Art of the Pre-Raphaelites. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000.

Rossetti, Dante Gabriel. The Correspondence of Dante Gabriel Rossetti. The Formative Years 1835-1854. Ed. William E. Fredeman. Volume 1. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2002.

Rossetti, William Michael. Selected letters of William Michael Rossetti. Ed. Roger W. Peattie. University Park and London: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1990.

Last modified 29 November 2021