Randolph Caldecott (1846–86) is ‘known to the world chiefly for his picture books.’ So writes Henry Blackburn in his memoir of the artist’s life and career (vii), and there is no doubt that Caldecott’s greatest achievement was his run of sixteen colour books for the nursery, which he published, with drawings engraved in colour by Edmund Evans (1826–1905), from 1878 to 1885. These small, paperback issues are widely regarded as a new departure in books for the very young and set new standards in design and production, as well as establishing a visual style that was influential in the 1880s and 90s and beyond.

History, Production, Economics, Dissemination

Caldecott’s Picture Books were initiated by Evans. The engraver and artist first met in 1878, when Evans was already established in the juvenile market as a leading publisher of coloured editions and, at this point, was trying to launch a new business venture. Since 1865 he had collaborated with Walter Crane as the producer of his Toy Books, and wanted to find someone who would extend or continue Crane’s type of publication (McLean 88). Evans had seen Caldecott’s black and white illustrations for Washington Irving’s Old Christmas and Bracebridge Hall (1875–77), and thought the artist would be ‘just the man to do some shilling toy books’ (Evans 56–57); the sixpenny books were lucrative and continued into the 80s, but Evans wanted to enhance his profits by offering items at a higher price (which would cost about £6 in modern sterling).

Caldecott immediately agreed to the businessman’s proposition that he should do a series, and, Evans remarks, ‘liked the idea of doing as I proposed’ (56). But the artist was not so naïve as to accept a flat sum for each book, insisting that he would take a share of the sales. The engraver notes, without comment, but with a weight of annoyed implication, that he had to ‘run all the risk of engraving the key blocks’ (my italics, 56), while Caldecott was prepared to work without pay if the books failed.

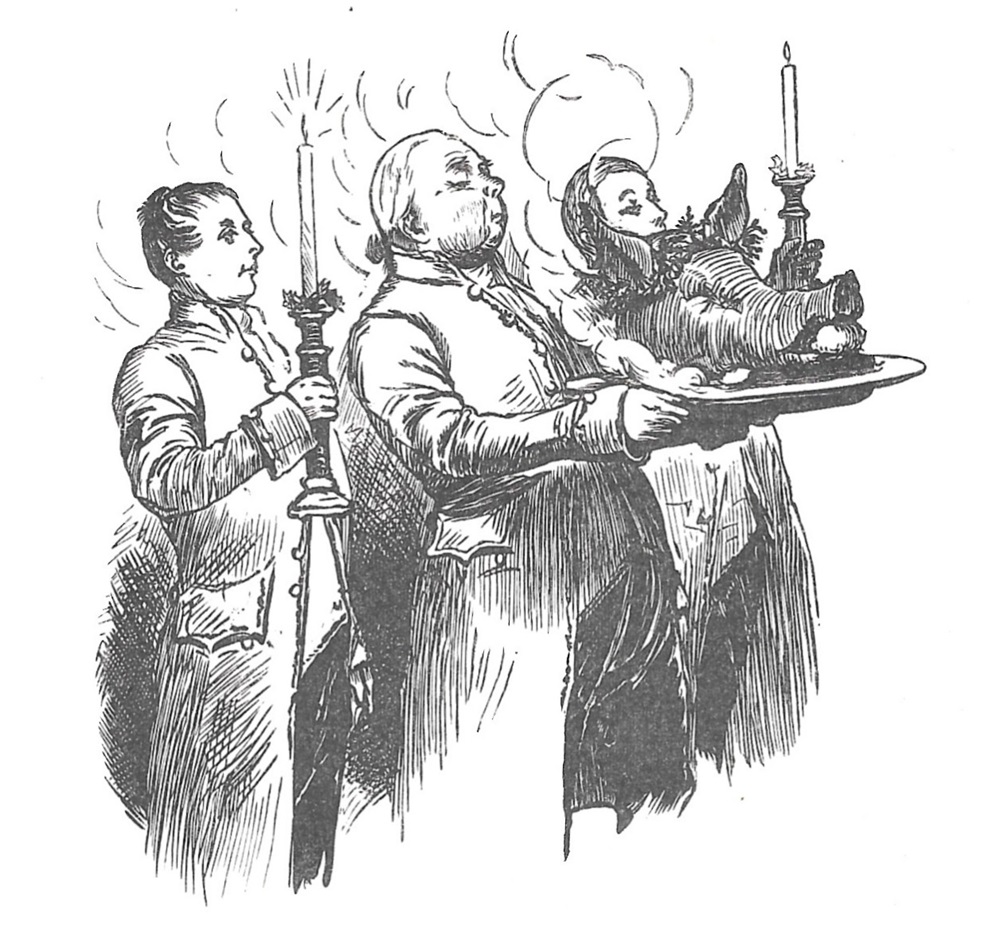

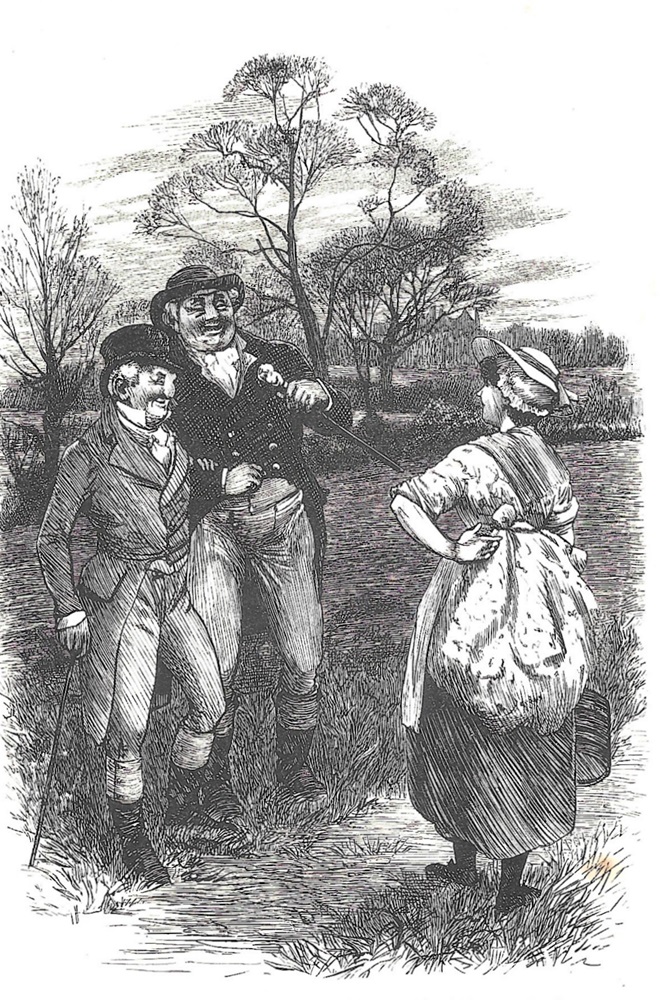

Two illustrations which impressed Edmund Evans. Left: A festive scene from Irving’s Old Christmas; and right: a rustic encounter from the same writer’s Bracebridge Hall.

This was a shrewd speculation on the artist’s part, and reflected the cautious nature of someone who, though he had worked for London Society, was still carefully placing the foundations of his career. He needed to find some advantage and, no doubt, was looking for ways to promote himself. Gaining a deal with the foremost colour printer of the age must have seemed a great step forward. Yet the engraver’s commitment was not quite as promising or generous as it might appear. Always looking for economies, Evans noted in his Reminiscences how he would absorb the expenses of cutting and printing but would only adopt the simplest model of production, with ‘as few colours as necessary’ (56); he was also to provide the paper and print 10,000 copies of each book, but cut costs by making use of George Routledge, a specialist in mass leisure publication who had access to a vast network. That network made it possible to distribute the books at the lowest possible cost.

Caldecott’s Picture Books were thus created as a partnership driven by economic considerations and the desire to refresh and re-animate an existing market. In other words, the arrangement was typical of the sort of deals that drove wood-engraved publications in the mid and latter part of the Victorian age; in particular, Evans’s practice echoes the model adopted by the Dalziels, the engravers who promoted the best woodblock artists of their age as part of their strategy to generate what were ultimately huge profits. The Dalziels were instrumental in the development of the style known as ‘The Sixties’ by providing books in which artists such as A. B. Houghton, George Pinwell and Fred Walker could display their work, and Evans was a driving force in the promotion of Caldecott, Crane, and later Kate Greenaway who between them became the foremost nursery artists of the age. If the Dalziels facilitated the rise of ‘poetic realism’ in the middle of the century, it is equally true to say that Evans was the proponent of the nursery and Regency styles of the 80s and 90s.

The production of the Picture Books was similarly very much in line with the protocols of the time, in part handicraft and in part a matter of industrial technologies. First of all, the artist drew his compositions ‘on smooth-faced writing paper, post 8vo size’; these were then ‘photographed on wood,’ that is, a negative would be printed on a boxwood surface, and was engraved. Some of the drawings would then be printed as outlines, while those that were supposed to be coloured were given to the artist as blanks and coloured in; with these as a guide, Evans’s craftsmen printed the tones using separate blocks. The ‘key block’ was ‘dark brown,’ a ‘flesh tint’ for the faces and hands, and red, blue, yellow and grey for the other parts of the designs (Evans 56).

The effect, throughout the books, is luminous, with the colours being very much enhanced by the yellow paper on which the designs were printed. In the 1850s Evans had made use of this type of paper to create the covers of the cheap reprints of popular fiction known as ‘Yellowbacks,’ and the engraver continued the bright and cheerful livery of those works in his production of Caldecott’s juveniles. What is also impressive – as in Evans’s printing of other coloured wood-block publications, such as Richard Doyle’s In Fairyland (1870) and James Doyle’s A Chronicle of England (1864) – is the engravings’ perfect register, with all of colours contained within their outlines. Though issued in limp covers and intended as ephemera which could be discarded once the child had lost interest, Caldecott’s Picture Books are small works of art, and were regarded as such as the time of production.

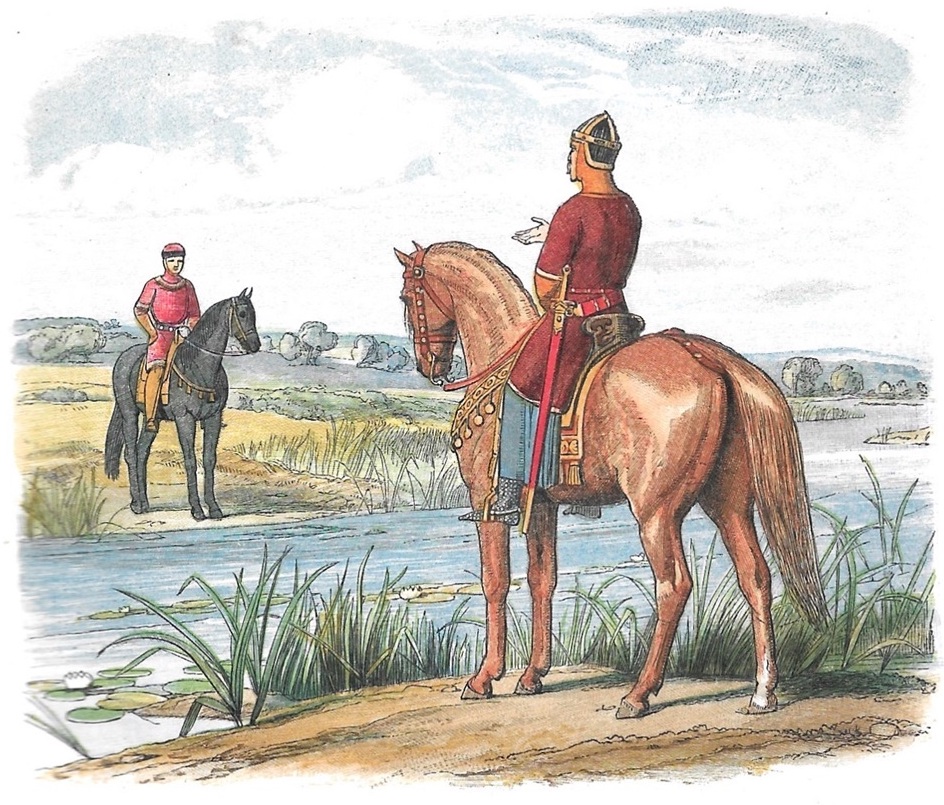

Two illustrations engraved using coloured wood blocks by Edmund Evans. Left: A scene from Richard Doyle’s In Fairyland, one of the masterworks of Victorian colour printing; and Right: An illustration from James Doyle’s A Chronicle of England, another remarkably fine piece of engraving which reproduces the effects of hand-coloured manuscripts.

They were certainly valued when they first appeared, and all sixteen were a huge commercial success. But Evans was able to exploit the books to even greater effect. Following on from the initial run of 10,000 for the first two publications and subsequent books in the series, the engraver consolidated his investment by reprinting all sixteen in books with four or eight issues in each volume, with paper covers and a cloth spine along with a new cover design by Caldecott to refresh the brand; and he also printed 1,000 copies in an ‘Edition de Luxe’ on larger paper, and signed by the publisher and printer (Evans 59). This luxury issue ‘sold immediately,’ and Evans, always the astute businessman, wished he had ‘printed three or four thousand instead of one thousand’ (59).

Despite this missed opportunity, Caldecott’s Picture Books were a huge, lucrative hit, and the partners were able to reap considerable financial rewards. The artist wrote to a friend early in the arrangement to say that he would only ‘get a small, small royalty’ (Hardie 281), but in the event the books made him plenty of money; clearly, his insistence on taking a share was a good move. Above all else, Evans’s venture made Caldecott into a household name and established his reputation as the foremost children’s illustrator of his time.

Style, Influence, and the Relationship of Word and Image

Caldecott was instrumental in the development of the ‘Regency style’ that was popular in the final quarter of the nineteenth century. The Picture Books showcase his iconography of an old-fashioned England in which the main emphasis is on picturesque landscapes, quaint costumes, small-town life, idealized peasants and swains, hunting – Caldecott was an enthusiastic horseman – rumbustious squires, cute children, and elegant ladies. This imagery is purely escapism, offering an imagined past; as Rodney Engen comments, Caldecott’s vision is ‘unmarked by the smokestacks of a distant factory’ (5) and postulates a paradisiacal, nostalgic alternative to the hard facts of an industrialized, ‘modern’ state. The pictures appearing in each of his books exemplify this quaint and emollient visual language. Caldecott’s imagery has a sort of timeless innocence, and his style is an appropriate medium for nursery tales. His is indeed the world of the child-like, a sort of Edenic perfection where, despite minor discord, life is essentially harmonious and unthreatening; Caldecott claimed to be a ‘conservative’ who disliked ‘innovation’ (Yours Pictorially 244), and there is a sense of his desire for stasis in his imagery.

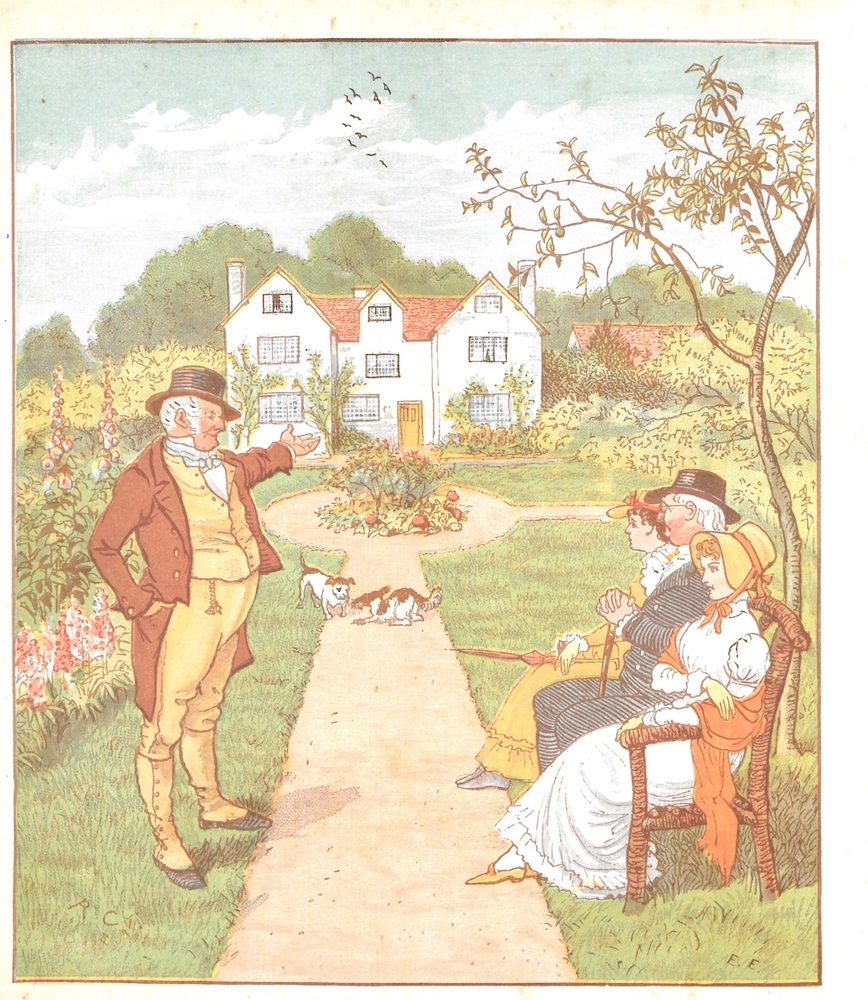

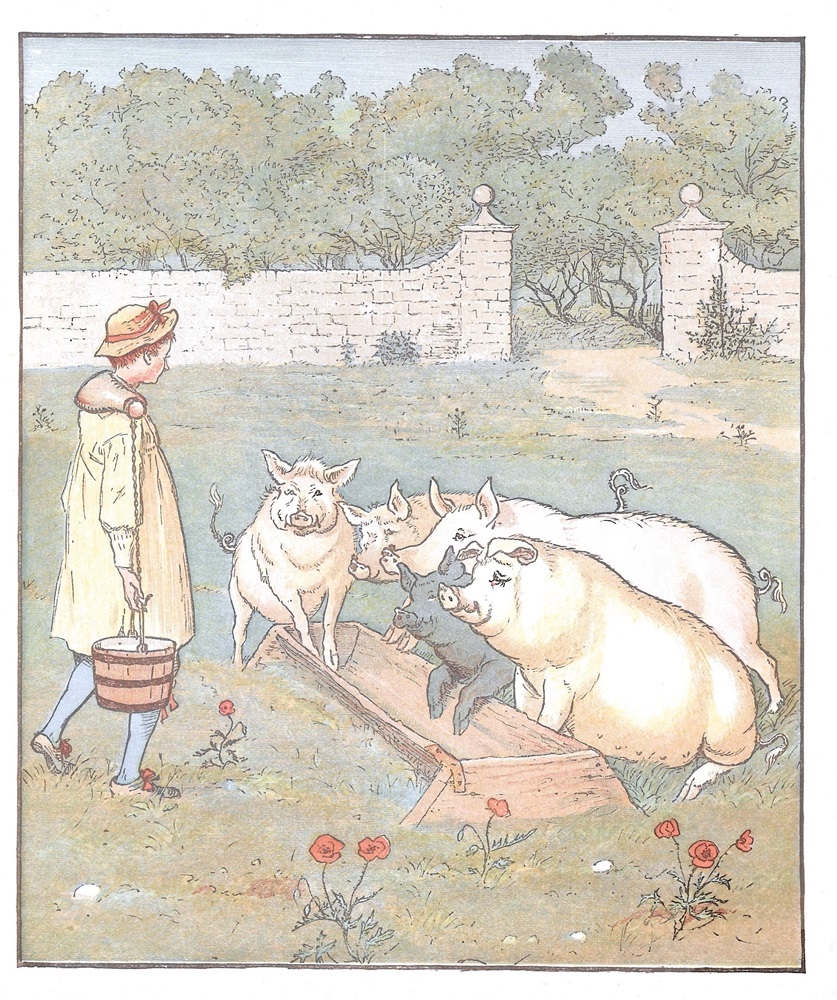

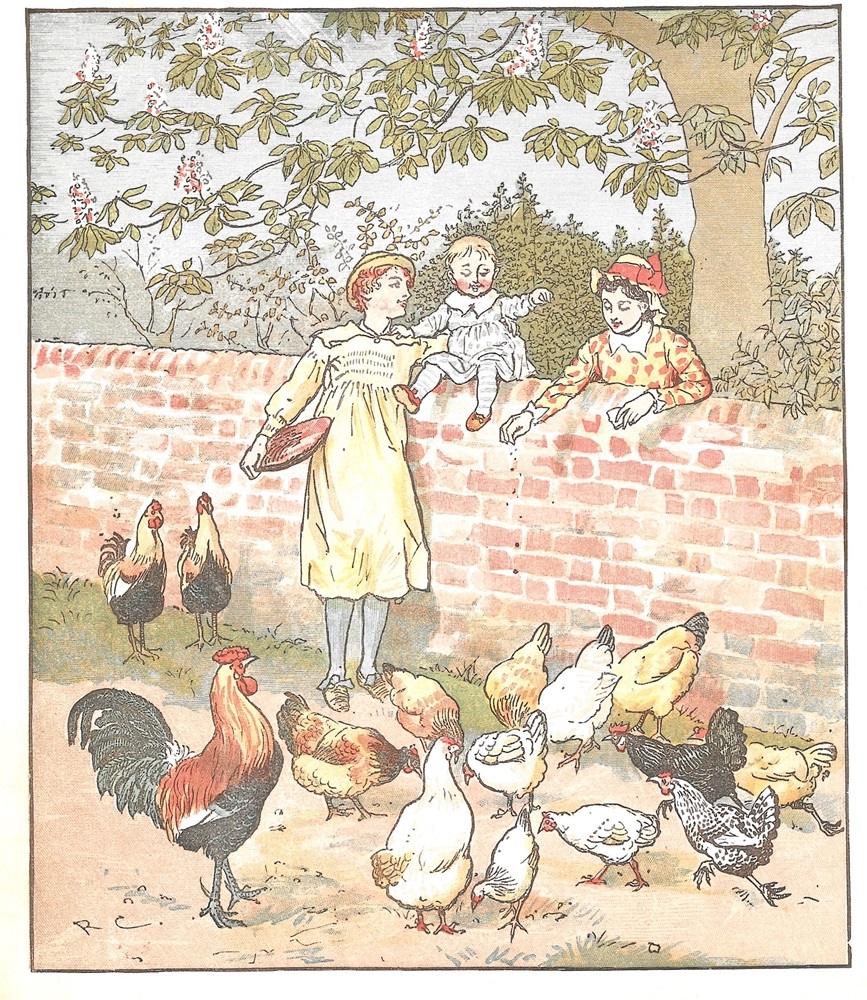

Three examples of Caldecott’s Edenic Old England, a place of innocence, old fashioned costumes, polite gentility and rustic swains. a) Gentlefolk sitting in the garden in The House that Jack Built, Caldecott’s first, signature book for Evans; b) Looking after the Master’s pigs in The Farmer’s Boy; and c) Looking after the Master’s chickens in the same book. Poverty or hardship never intrudes into Caldecott’s escapist imagery of the rustic past – God’s in his Heaven, and all is right with the world.

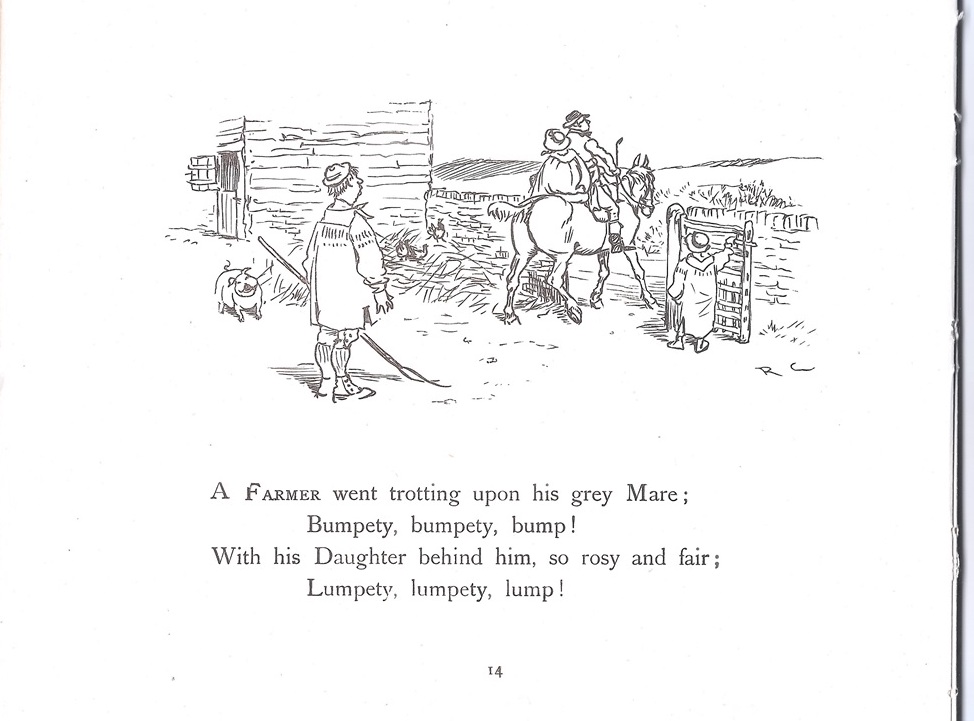

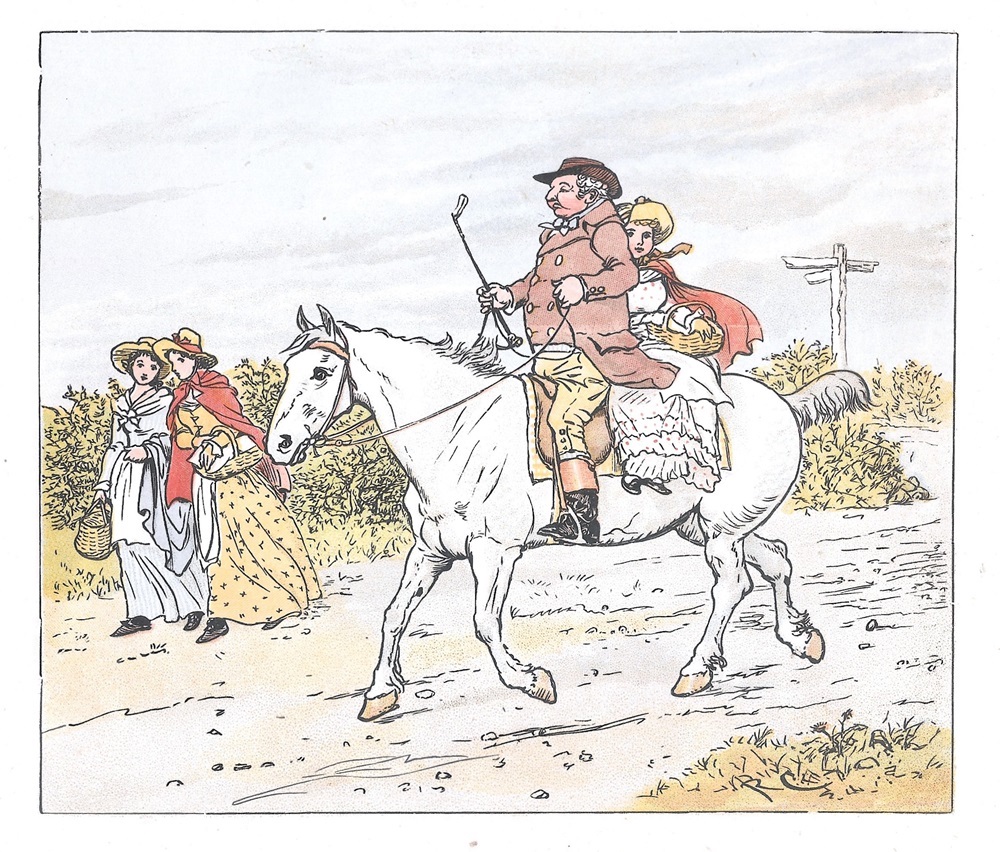

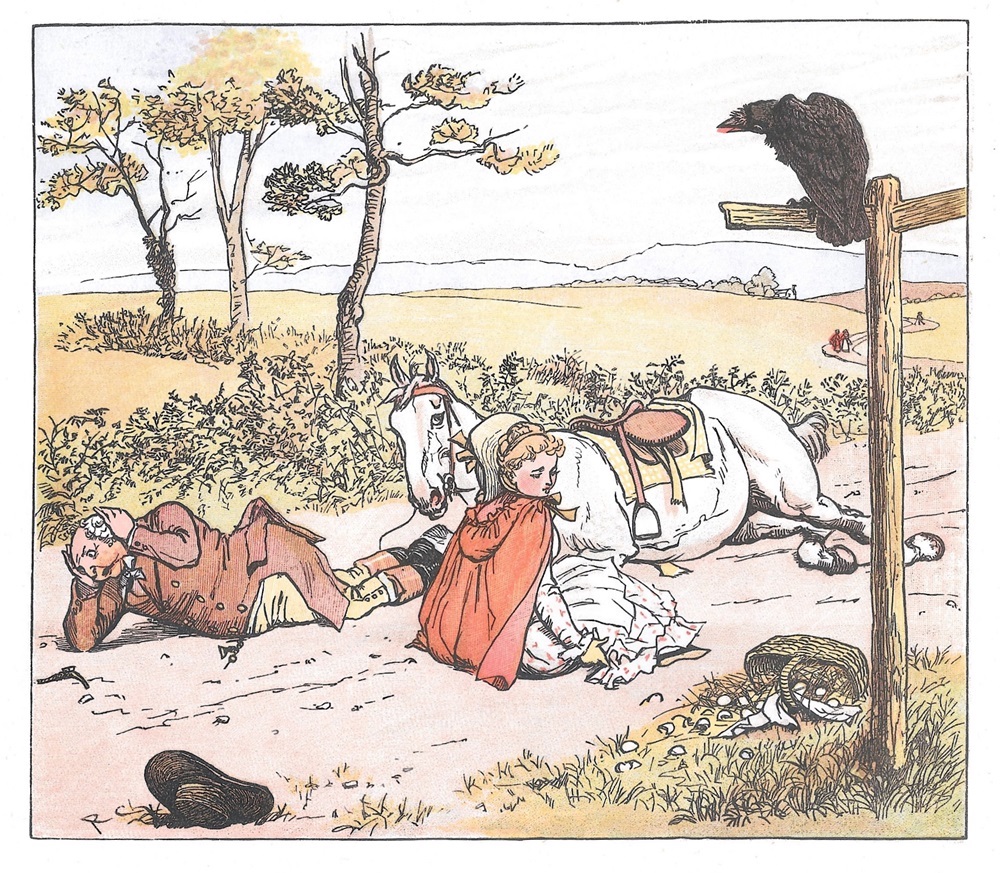

It is aimed, of course, at the very young, and his books take the form of a series of very simple storyboards accompanied by a few words of nursery-rhyme narrative. Taken together, this arrangement is a continuation of early reading books in which the infant’s gaze is directed from the text to the illustration and the process of acquiring the rudiments of literacy is facilitated by checking the words against an image or images. A prime example of this process can be seen in the illustration of the rhyme appearing in the second part of Ride a Cock Horse … and a Farmer Went Trotting Upon His Grey Mare, in which the narrative is visualized as a pictorial sequence. The rhyme is a simple description of the Farmer and his Daughter, mounted on the Mare as they jog off, ‘Bumpety, bumpety, bump!’, and the illustration shows exactly that scene in simplified, simplistic, diagrammatic terms. The narrative is then carried forward in the illustrations within the text, one in colour and one in outline; these lead to the next important scene, which is again a combination of a text – describing the Raven’s croaking – and pictures showing the bird’s intervention alongside the characters’ fall from the horse. The words and images are thus placed in physical proximity and intermingled so that what is read or spoken is inextricably fused in synergy. Such dynamic interactions combine into a seamless whole, acting to project an imaginative world of great intensity, and one calculated to appeal to the magic consciousness of infanthood.

Left to right: three stages in the montage that visualizes the story of the Farmer and his Daughter as they move from a proud trot to a calamitous fall.

It is not clear which of the partners was the author of this balanced arrangement of image and word: it could have been Caldecott’s idea, though it is likelier, I believe, to be Evans’s. Evans was after all a specialist in children’s books and was far more familiar with the forms of juveniles than the artist, whose earlier work was directed at an adult audience. On the other hand, the format could have been a collaborative effort – drawing together a producer who wanted to make his books as accessible as possible, and an artist who was capable of encapsulating ideas in lucid forms: Caldecott was an effective storyteller, and the drawing of comic situations in his earlier work is applied to great effect in these narrative works for children.

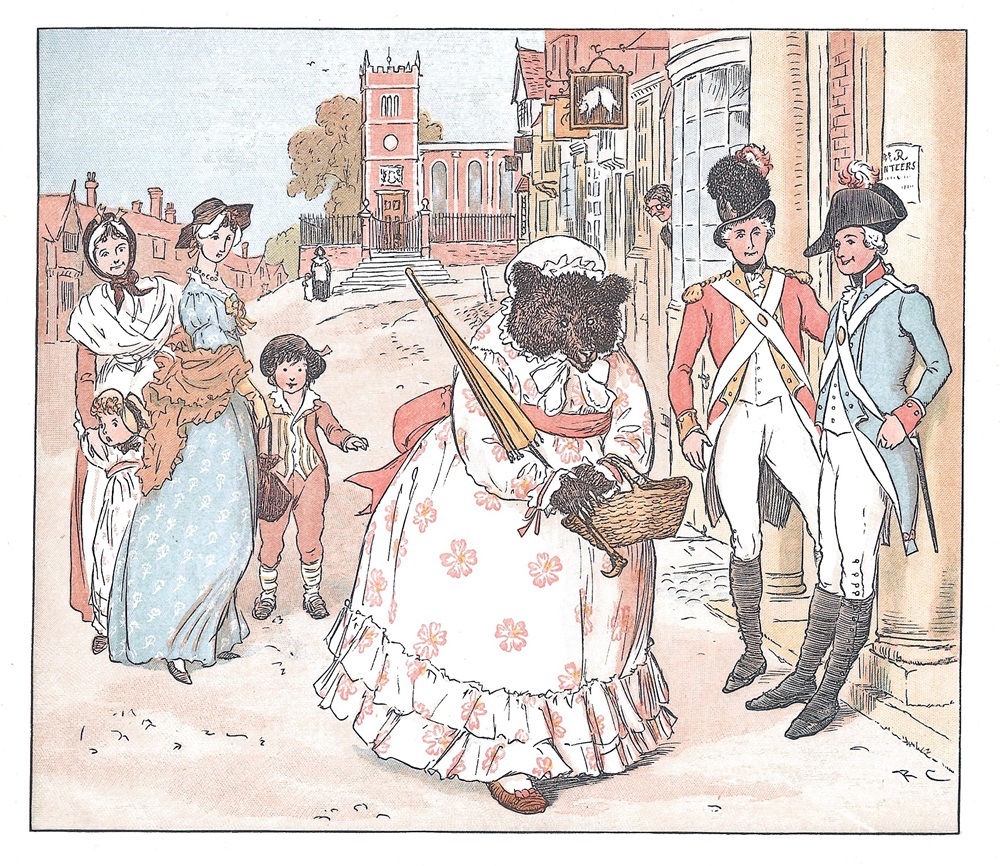

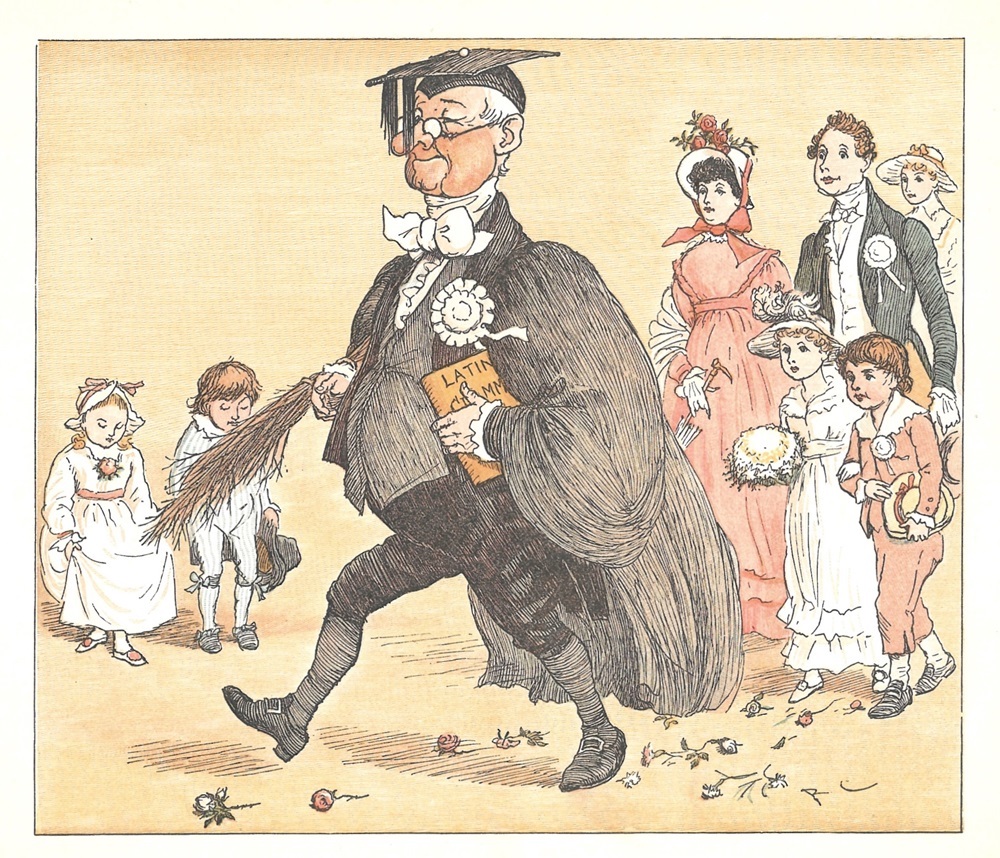

Drawing on this experience as a cartoonist, Caldecott infuses his stories with humour and energy. In the words of his friend Walter Crane, his illustrations for the Picture Books have ‘extraordinary vivacity.’ (183), and, like many books for children, are designed to appeal to the juvenile readers and to the adults who helped the youngsters navigate the pages. In his illustration for ‘Hey diddle diddle’ the emphasis is very much on the humour of infancy, with the Dish and the Spoon being personified as characters with faces and running legs; the effect is slightly surreal, but was sure to appeal to a three-year-old. The same is true of the characterization of the ‘great she-bear,’ who is depicted incongruously as a genteel lady, complete with an umbrella and a basket. In both cases, Caldecott plays on the intersection between illustration and toys, with his persona appearing almost as if they could exist as play-figures in the toy-cupboard. In the characterization of the Great Panjandrum, on the other hand, Caldecott draws upon a more adult humour, depicting the schoolteacher as a fusty old scholar in a style that recalls the humorous manner of John Leech.

Three examples of Caldecott’s humour: a) The Dish running away with the spoon; b) ‘the great she-bear;’ and c) the Great Panjandrum.

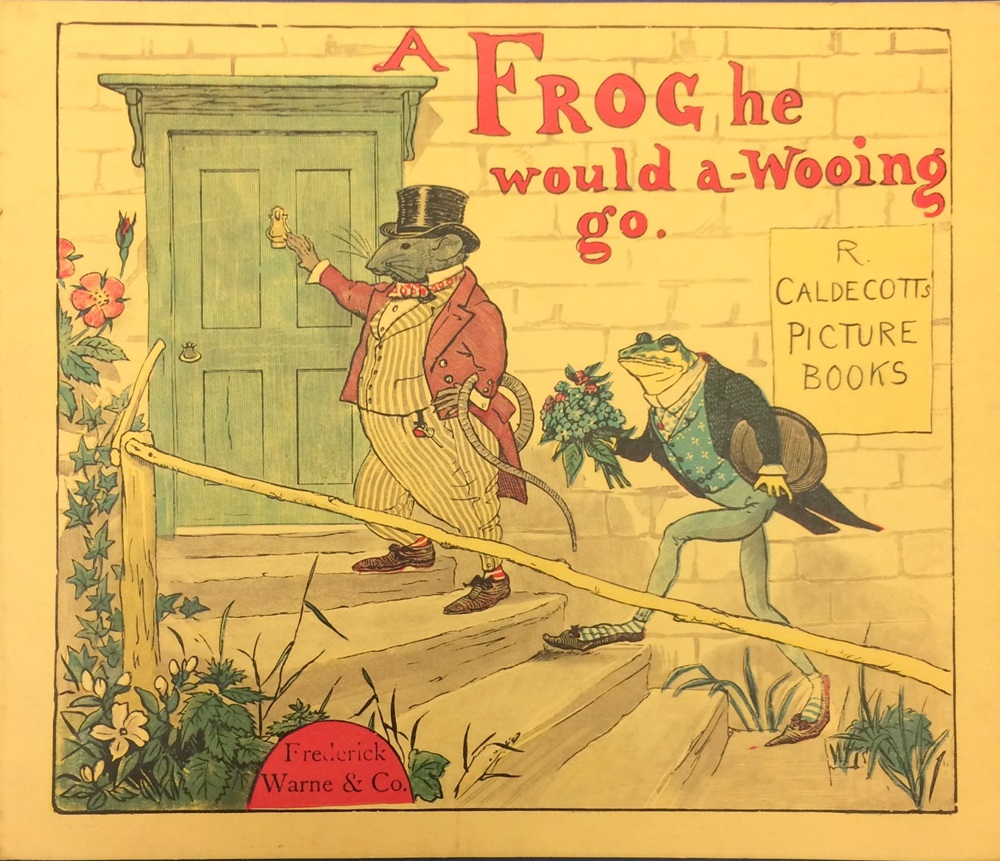

The inventiveness and comedy of these books has wide appeal, and it is unsurprising that they were so popular. Caldecott’s Picture Books are a highly significant contribution to the development of juveniles – and small masterworks which exemplify the fine effects that could be produced using the mass-medium and industrial modes of production that characterize the Victorian book trade. They were influential too. Caldecott’s Regency imagery was a direct influence on Hugh Thomson, who created the so-called ‘Cranford style,’ and Caldecott’s personification of animals was similarly important as a source for Beatrix Potter, who pored over the artist’s work. The connections between Caldecott and these later artists are plain, and we have only to compare a few examples. ‘The Frog he would a wooing go’ and the illustration of the great She Bear are clearly inspirations for Potter’s anthropomorphism, and Thomson’s polite depictions of social mores can be compared to many of Caldecott’s images of eighteenth century costumes and old-fashioned interiors.

Left: one of Caldecott’s anthropomorphic images; and Right: an example of Beatrix Potter’s cute animals.

Bibliography

Primary

Doyle, James. A Chronicle of England, B.C. 55 – A.D. 1485. London: Longmans, Green, 1864.

Doyle, Richard. In Fairyland. London: Longmans, Green, 1870.

The Farmer’s Boy. London: Routledge [1881].

The Great Panjandrum Himself. London: Routledge [1885].

Hey Diddle Diddle and Baby Bunting. London: Routledge [1882].

The House that Jack Built. London: Routledge, 1878.

Irving, Washington. Bracebridge Hall. London: Macmillan, 1875.

Irving, Washington. Old Christmas. London: Macmillan, 1877.

Ride a-Cock Horse to Banbury Cross and A Farmer Went Trotting Upon His Grey Mare. London: Routledge [1884].

Secondary

Blackburn, Henry. Randolph Caldecott: A Personal Memoir of His Early Art Career. London: Sampson Low, 1886.

[Caldecott, Rudolph]. Your Pictorially. Ed. Michael Hutchins. London: Warne, 1976.

Crane, Walter. An Artist’s Reminiscences. London: Methuen, 1907’

Engen, Rodney. Randolph Caldecott: Lord of the Nursery. London: Oresko Books, 1976.

Evans, Edmund. Reminiscences. With an introduction by Ruari McLean. Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1967.

Hardie, Martin. English Coloured Books. 1906; rpt. London: Fitzhouse Books, 1990.

McLean, Ruari. Victorian Book Design and Colour Printing. London: Faber and Faber, enlarged edition, 1972.

Created 13 September 2024