“The story of the beautiful is already complete – hewn in the marbles of the Parthenon – and broidered, with the birds, upon the fan of Hokusai – at the foot of Fusiyama.” James McNeill Whistler, The “Ten O’Clock” Lecture.

“I mean by a picture a beautiful romantic dream of something that never was, never will be - in a light better than any light that ever shone - in a land no one can divine or remember, only desire - and the forms divinely beautiful.” Edward Burne-Jones.

Nocturne: Blue and Silver — Chelsea by James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834-1903). 1871. Oil on wood. Support: 502 x 608 mm; frame: 685 x 825 x 45 mm. Tate Britain, bequeathed by Miss Rachel and Miss Jean Alexander in 1972. Reference T01571. Kindly made available under the Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND (3.0 Unported) licence.

he Aesthetic Movement, the second of the major British avant-garde art movements of the latter half of the nineteenth century, represented a rapid advance in ideas regarding the role of art in society. The influence of the Aesthetic Movement was felt widely and embraced all branches of the fine and decorative arts, including architecture and interior decoration, as well as design in general. It helped to break down what was considered the traditional boundaries between the fine and decorative arts. In fact the involvement of some of these artists in the decorative arts was to have a profound effect on the paintings they produced, particularly in the case of Edward Burne-Jones.

The Aesthetic Movement was largely a reaction against the ugliness and vulgar materialism of industrialized nineteenth-century Britain. Many of the proponents of this movement felt that only beauty could provide a refuge from scientific technological advances and the horrors of industrialization and looked with nostalgia to classical antiquity or the Middle Ages as times which were simpler and for nobler than their own. As Stephen Calloway has explained: “Theirs was to be ‘Art for Arts’s sake’ – an art self-consciously absorbed in itself, aware of the past but created for the present age, and existing only to be beautiful” (11). Although Aestheticism reached its zenith in terms of its influence and its popularity with the general public in the late 1870s and the 1880s, much of its most interesting work was carried out in its formative years in the late 1850s and the 1860s, when it was truly an avant-garde development. What makes the 1860s such a fascinating period is that at no other time were the interpersonal relationships closer, or was there more collaboration and cross-influences between the principal protagonists associated with this movement. They took inspiration from what one another thought and did, and this resulted in a new direction for art.

There are a number of ways in which the shared interests and styles amongst this group of painters came about. The Hogarth Club, although it existed for only a short period of time from April 1858 to December 1861, provided a place for progressive artists and architects to meet and where their work could be shown to a restricted appreciative audience. The Hogarth Club exhibitions provided an opportunity for this progressive group of artists to be aware of what their fellow artists were engaged upon. Among its artistic members were Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Burne-Jones, Arthur Hughes, William Holman Hunt, Ford Madox Brown, Frederic Leighton, William Morris, Val Princep, William Bell Scott, Frederic William Burton, John Roddam Spencer Stanhope and George Frederic Watts.

Progressive architects that were members included G. F. Bodley, Philip Webb, and William Burges. Some of these same artists and architects were members of the Mediaeval Society. Many were also members of the Artists’ Volunteer Corps (Artist Rifles), founded in 1860 as part of the general movement to combat the threat of French aggression under Napoleon III. Among its members were Rossetti, J. E. Millais, Holman Hunt, Brown, Burne-Jones, Morris, Stanhope, Algernon Swinburne, Leighton, Watts, William Blake Richmond, Simeon Solomon, and Henry Holiday.

A number of the artist associated with the early Aesthetic Movement trained in Paris or elsewhere on the continent such as James McNeill Whistler, Edward Poynter, Prinsep, Thomas Armstrong, Leighton, and Lawrence Alma-Tadema. Some had been students together at the Royal Academy schools, including Holiday, Solomon, William de Morgan, William Blake Richmond, and Albert Moore. Many of these artists, even if they had not trained on the continent, spent much time living or travelling there, particularly to Italy. The letters, reminiscences, and diaries of the period by artists such as Rossetti, G. P. Boyce, Brown, Holiday, Walter Crane, and George du Maurier are full of meetings between the various artists at their homes or studios, or at the homes of the Ionides family, or at Arthur Lewis‘s bachelor musical evenings.

Work with Book Illustration, Architecture, and Furniture Manufacturers

Most of these artists were struggling financially when they were beginning their artistic careers and so were glad to be offered work as illustrators for magazines such as a The Cornhill Magazine, Once a Week, or Good Words. Many artists who were to make important contributions to the Aesthetic Movement provided illustrations in the 1860s for the Dalziel Bible Gallery, including Leighton, Poynter, Watts, Burne-Jones, Solomon, Frederick Sandys, Holman Hunt, and Brown.

The artists associated with the early Aesthetic Movement also tended to collaborate with architects on decorative work such as murals for buildings or churches, on stained-glass designs for James Powell and Sons or Morris, Marshall, Faulkner and Co., or collaborate on decorative furniture with progressive architect and designers like J. P. Seddon, William Burgess, and E. W. Godwin for manufacturers like Seddon & Co., Collinson and Lock, and Cottier & Co. Because many of these artists’ works were frequently rejected by the Royal Academy, they often exhibited their paintings and watercolours at the Dudley Gallery, which was the most popular artistic venue for progressive artists until the opening of the Grosvenor Gallery in 1877. This was particularly true for a group of young artists dubbed the “Poetry Without Grammar School” by hostile critics. The leading artistic figures of the Aesthetic Movement were Rossetti, Burne-Jones, Whistler, Moore, Leighton, Watts, and Solomon, but a great many other artists were associated with this movement.

Aesthetic, Greek Aisthesis, and perception of things by the senses

The term “Aesthetic” was derived from the Greek “aisthesis”, signifying perception of things by the senses. Aestheticism arose in the late 1850s, centered on the artists associated with the second phase of Pre-Raphaelitism and the Classical Revival of the 1860s, particularly what is termed “Aesthetic Classicism.” The beginning of the second phase of Pre-Raphaelitism can be said to date to 1857 with the decoration of the Oxford Union Debating Hall by Rossetti and six other artists, many of who would play a large part in the early Aesthetic Movement. The Aesthetic Movement was by no means a homogeneous style, and the influences on its practitioners were diverse, including ancient Greek sculpture, mediaeval illuminated manuscripts, Renaissance paintings of the 15th and 16th century, Japanese art, and even the Spanish master Velasquez. Every artist within the movement did not necessarily feel these influences and different influences might predominate at different phases of an artist’s career. The work produced by the artists associated with the Aestheticism therefore tends to be rather eclectic. The artists associated with the nascent Aesthetic Movement were interested in the love a beauty for itself and the rejection of sentiment and morality in art, which is different from what the Victorian public in general would have seen as the purpose of art at this time

In the words of Whistler in his Ten O’Clock lecture: “Art should be independent of all clap trap - should stand alone, and appeal to the artistic sense of eye or ear, without confounding this with emotions entirely foreign to it, as devotion, pity, love, patriotism and the like. All these have no kind of concern with it” (Whistler, Gentle Art, 127). Aesthetic Movement art primarily emphasized the decorative abstract values of a harmonious arrangement of form, line, and color. Some of the exponents of Aesthetic Classicism and the second phase of Pre-Raphaelitism, however, did not entirely reject subject matter and drew inspiration from ancient historical, mythological, biblical, or literary sources. It would be a mistake to think that all the artists associated with the Aesthetic Movement intended their paintings to purely give sensual visual pleasure. Certainly painters like Watts and Leighton felt that beauty was, in itself, a moral force and they intended their works to be ennobling and uplifting, while an underlying symbolic meaning can frequently be found in the works of Rossetti, Burne-Jones, and their followers. Even when some narrative continent was retained, however, the emphasis was still on achieving a harmonious arrangement of form and tones, and the overall decorative effect of the work was still its predominant purpose.

Théophile Gautier, Charles Baudelaire, and L’Art pour L’Art (Art for Art’s Sake)

The artistic theories fashionable in the late 1850s and early 1860s in the circle of artists and poets centred around Dante Gabriel Rossetti originated in France in the writings of Théophile Gautier and Charles Baudelaire, the principal proponents of L’Art pour L’Art (Art for Art’s Sake), who felt that art should concern itself only with beauty and be free of all religious, moral and ethical constraints. In 1857 Baudelaire published his notorious book of poems Les Fleurs du Mal (The Flowers of Evil) which was influential in spreading this new philosophy of art. Swinburne read Les Fleurs du Mal in the expurgated edition of 1861 and wrote an enthusiastic letter about the poems to Baudelaire, as well as an article on them for The Spectator, published in September 1862. Although Swinburne and Baudelaire never met, Baudelaire sent Swinburne a copy of his pamphlet Wagner and Tannhauser as thanks for his complementary article. From this pamphlet Swinburne gained insight into “correspondences.” The concept that the various Arts shared common properties and consequently could exchange them was to be of vital importance to the practitioners of the early Aesthetic Movement in England. This idea of the interrelationships between various art forms, and particularly between music and painting, was not new and first began to be seriously explored in the eighteenth century (Scheuller, Correspondences, 334-59). Nineteenth century artists and writers explored the interrelationships between the arts by examining how one sense could activate another through “synaesthesia”, and how the perception of one form of artistic activity gives rise to sensations normally caused by another. Walter Pater was later to expound further on this in 1873 in his essay “The School of Giorgione” (complete text) writing that “All art constantly aspires towards the condition of music” (140). The analogy between music and painting by the artists associated with Aestheticism was carried to the most extreme by Whistler, who referred to his paintings as Notes, Harmonies, Symphonies, Nocturnes or Arrangements.

Nocturne: Blue and Silver – Cremorne Lights. James McNeill Whistler. 1872. Oil on canvas, 19 3/4 x 29 1/4 inches (50.2 x 74.3 cm). Collection of Tate Britain, reference no. N03420. Click on image to enlarge it.

The Blue Closet Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882). 1857, Watercolour on paper 14 x 10 ¼ inches (35.4 x 26.0 cm). Collection of Tate Britain, accession no. N03057

Rossetti‘s awareness of the interrelationship between music and other art forms became increasingly evident in both his paintings and poetry in the late 1850s. This may have been partly due to his friendship with Swinburne, whom he had first met in 1857 during the mural decorations of the Oxford Union Debating Hall while Swinburne was still an undergraduate. Rossetti was obviously aware of these concepts even prior to that time, however, and Rossetti’s ideas on the purpose or art and poetry had a great influence on Swinburne as well. If one attempts to trace back the first paintings which inaugurate the Aesthetic Movement, then certainly strong consideration must be given to the mediaeval “Froissartian” watercolours painted by Rossetti in the late 1850s, with their bold complex abstract decorative patterns of flat brilliant color. The earliest of these, The Blue Closet, although dated 1857 must have been almost complete by the end of 1856 because William Morris had written a poem at that time inspired by the watercolor. Rossetti showed the importance he placed on this painting by exhibiting it at the first Pre-Raphaelite joint exhibition held in Russell Place in 1857. The critic F. G. Stephens was aware of how the concept of correspondences related to this painting, perhaps through discussions with Rossetti himself about the work:

“As to the association of colour with music – of which this drawing is a subtle instance, more recondite than any of the those examples where several old masters, and especially Rossetti himself, had made the colouration of their pictures subserve the pathetic expressiveness of their subjects – we may notice that the sharp accents of the scarlet and green seem to go with the sound of the bell; the softer crimson, purple, and white accord with the throbbing notes of the lute and the clavichord, while the dulcet, flute-like voices of the girls appear to agree with those azure tiles on the walls and floor which give to this fascinating drawing its name of The Blue Closet. [42]

The Surprising Role of Millais

The only other artist who could readily be associated with the genesis of the Aesthetic Movement in England is John Everett Millais. This is very surprising because Millais had been largely estranged from the Rossetti circle since his election as an associate of the Royal Academy at 1853 and in terms of his later artistic output. While Millais had been the most important and influential painter during the first phase of Pre-Raphaelitism, his later works after the 1860s were largely conventional, full of sentimentality, and totally removed from the precepts of the Aesthetic Movement. In 1855–56, however, Millais set out to paint one of his most important pictures, Autumn Leaves, of which his wife Effie says in her journal: “he wished to paint a picture full of beauty and without subject” (Warner 137).

Left: Autumn Leaves. Sir John Everett Millais Bt PRA (1829-96). 1855-56. Oil canvas, 41 x 29 inches. City Art Galleries, Manchester. Right: Apple Blossoms or Spring. 858-59. Millais. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of the Lady Lever Art Gallery, Port Sunlight, Wirral.

Although Autumn Leaves was intended to create a mood and be without narrative content, the work is actually about mortality, with the images of decay that surround the young girls being intended to remind us that youth and beauty such as theirs, as well as life itself, are transitory. As such this painting is not “subjectless” in the same sense, for instance, as Rossetti’s The Blue Closet or The Tune of the Seven Towers. Autumn Leaves was an important forerunner of the Aesthetic Movement, however, in its desire to create beauty, in its use of symbolism as an alternative to subject, and it’s introduction of the use of the passive beautiful feminine face. The mood conveyed by a painting became as important as its subject. Millais only painted one other exercise in Aestheticism, Apple Blossoms [Spring] that he worked on from 1856-59. This painting continued the theme that Millais had earlier developed in Autumn Leaves of the transience of youth echoed in the changing seasons. It was another of his “mood-pictures” that allowed him to introduce symbolic meaning to his works without recourse to narrative clues or ostensible subject matter.

Aesthetic Movement painters were obsessed by beauty, particularly feminine beauty. Portraying female figures, either singular or in a group, in a state of reverie, dreaming, or asleep was to become a characteristic feature of the work of artists associated with the Aesthetic Movement, particularly Leighton, Burne-Jones, and Moore, as they searched for an ideal abstract beauty in art devoid of any overt narrative content. The concept behind painting these passive static female figures with expressionless faces in an attempt to achieve ideal beauty may be based on ancient Greek sculpture. It may also derive from the Fifth Discourse of Sir Joshua Reynolds: “If you mean to preserve the most perfect beauty in its most perfect state, you cannot express the passions, all of which produce distortion and deformity more or less in the most beautiful faces” (Warner 138). Millais was certainly aware of these concepts while painting Autumn Leaves, as he expressed his theoretical beliefs on beauty in a letter to Charles Allston Collins: “when a particular expression shows itself in the face, then comes the occasion of difference between people as the whether it increases or injures the beauty. Now this is evidently the game the Greeks played in Art, they avoided all expression, feeling that it was detrimental to beauty according to the capacity of understanding in the mass” (Warner 137). Aesthetic Movement painters created an entirely new type of female beauty in comparison to what had previously been considered alluring in British art. Often, however, this dazzling feminine beauty was portrayed with an unconcealed and frank sensuality, particularly in the work of artists such as Rossetti, Sandys, and Solomon.

1859 — Frederic Leighton and James McNeil Whistler Move from Paris to London

The year 1859 was an important turning point in the Aesthetic Movement. In this year not only did Frederic Leighton and James Whistler take up residence in London after periods of study in Paris, but Rossetti produced the first of his bust-length oil paintings of beautiful sensual women, Bocca Baciata. This painting was exhibited at the Hogarth Club where it was widely seen by a restricted audience and it was to have to a profound influence on Rossetti‘s contemporaries and on the later productions of the Aesthetic Movement. It set the fashion for half-length female portraits in a Venetian Renaissance style. Others within the Pre-Raphaelite circle were soon producing “fancy portraits” in a similar style including Edward Burne-Jones,Brown, Sandys, Solomon, Scott, Burton, Watts, and Prinsep. In 1859 Leighton was also producing similar paintings in his “La Nanna” series, such as his A Roman Lady or La Pavonia, although these were more influenced by Florentine than Venetian Renaissance prototypes. Leighton would later paint works in a Venetian style as well such as his A Noble Lady of Venice of 1866.

Three of Rossetti’s “stunners”: Left: Boca Baciata. 1859. Oil on panel, 12 ⅝ x 10⅝inches (32.1 x 27 cm). Exhibited 1860. Collection of Boston Museum of Fine Arts, accession no. 1980.261. . Middle: Lady Lilith. Oil on canvas, 38 x 33 1/2 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Wilmington, Delaware. Right: The Beloved. 1865-66. Oil on canvas, 32 ½ x 30 inches. Collection of Tate Britain, reference no. N03053.

Rossetti produced a large series of paintings of sensual “stunners” in the 1860s including Fair Rosamund of 1861, Helen of Troy of 1863, Fazio’s Mistress of 1863, Monna Pomona of 1864, Venus Verticordia of 1864-68, Lady Lilith of 1864-68, The Blue Bower of 1865, The Beloved of 1865-66, Mona Vanna of 1866, Regina Cordium of 1866, A Christmas Carol of 1867, and Sibylla Palmifera of 1866-70. These are now many of the works for which he is best known.

Rossetti’s Influence Passes to Burne Jones

Rossetti‘s influence on the followers of the second phase of Pre-Raphaelitism began to fall in the 1870s, partly due to his refusal to exhibit publicly, but also due to his increasing reclusiveness after his mental breakdown in 1872. Due to these factors the leadership of the movement passed to Edward Burne- Jones. Burne-Jones’s art in the late 1850s had been largely influenced by Rossetti and Ruskin, and much of his work was in pen and ink and mediaeval in inspiration. Following visits to Italy in 1859 and 1862 he quickly began to develop his own individualistic style and he began to explore the great many cross-currents affecting progressive British art at that time. Burne-Jones was both influenced by, and influenced, many of his contemporaries, particularly artists close to him like Stanhope and Solomon, but also artists on the more extreme fringe of the Aesthetic Movement like Whistler and Moore. Burne-Jones was the prime inspiration for a group of younger painters, including Robert Bateman, Crane, and Edward Clifford, who exhibited at the Dudley Gallery and were dubbed by hostile critics “The Poetry Without Grammar School.”

Left: Green Summer by Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones, Bt ARA. 1873-75. Watercolornd gouache on paper, 11 ⅜ x 18 ⅛ inches (29 x 48.3 cm). Exhibited Old Water Colour Society, 1865, no. 105. Private collection. Right: The Lament by Burne-Jones. 18 ¾ x 31 ¼inches (47.5 x 79.5 cm). Collection of the William Morris Gallery, Walthamstow.

In the early 1860s, from about 1860-64, Burne-Jones produced a series of watercolors, small in scale, which despite their technical limitations are remarkable in their originality. Venetian influences were of paramount importance, particularly Carpaccio and Giorgione. In work such as Green Summer, which was a harmony in green, and The Flower of God, which was a harmony in red, Burne-Jones was producing colour harmonies that were equal to, and perhaps even in advance of, anything being produced by Whistler and Moore at this time. Burne-Jones and his followers were much more influenced by early Italian painting than were the artists of the first phase of Pre-Raphaelitism. No one would ever mistake a work by this earlier group of Pre-Raphaelites for a quattrocento painting but this was certainly possible with the painters of the second phase. In 1867 the architect G. F. Bodley bought Burne-Jones large triptych The Adoration of the Kings and Shepherds (centre) and The Annunciation (wings) for £50 from a man “who had no idea but that it was an old Italian picture.” Most of these second-generation Pre-Raphaelite painters gathered limited recognition or praise when their works were exhibited at public exhibitions. Critics for well-known contemporary periodicals who reviewed art exhibitions at the Royal Academy or the Dudley Gallery criticised the works of Burne-Jones and his circle as “modernized Medievalism”, “mediaeval mimicry,” “pseudo-classicality,” or as the “pseudo-quattrocentist school.” Despite being inspired by the art of the past, these artists were not interested in merely copying the Old Masters and resented being accused of that by critics. William Morris, in an interview in 1893 by The Daily Chronicle regarding the Holy Grail Tapestries, designed by Burne-Jones and made by Morris & Co., summed up what most of the artists in their circle felt about beauty in 19th century England:

’Good gracious!’ replied Mr. Morris, ‘what is there in modern life for the man who seeks beauty? Nothing - you know that quite well. To begin with, if you want to make beautiful people you’ve got to drop modern costume. Besides, the line of tradition is broken, and you must work in some skin. Here are people with high art interests - what are they to do? ‘Make a new style,’ you say? But that takes a thousand years! The Holy Grail people were working in a straight line of tradition - that line is broken; we have nothing like a stream of inspiration to carry us on. The age is ugly - to find something beautiful we must ‘look before and after.’ Of course, if you don’t want to make it beautiful, you may deal with modern incident, but you will get a statement of fact - that is, science. The present days are non-artistic and scientific - that is at the bottom of the whole question, and we are not to be blamed…No, if a man nowadays wants to do anything beautiful he must choose the epoch which suits him and identify himself with that - he must be a thirteenth-century man, for instance. Though, mind you, it isn’t fair to call us copyists, for in all this work here, which you complain of as being deficient of a particle of modern inspiration, there is no slavish imitation. It is all good, new, original work, although in the style of a different time.”

From 1865 onwards the direction of Burne-Jones’s art changed once more as Rossetti‘s influence waned and he became more influenced by Aesthetic Classicism. His work became more decorative, with paler tones and clearer colours. His technical competency improved as well because the faulty draftsmanship, which had plagued his earlier work, was overcome by constant practice in drawing the nude figure, and from studying ancient classical sculpture in the British Museum.

At no other time in his career was Burne-Jones’s work closer to that of Albert Moore and James Whistler, particularly in works like The Lament, dated 1866, but largely painted in 1865. This work was inspired by the Elgin Marbles and Italian Renaissance art, and approaches Moore’s and Whistler‘s works in its restrained colour harmonies, and the decorative use of a sprig of roses at the periphery of the painting. It has no real subject and seeks primarily to evoke a mood. Through the influence of Whistler and Moore, Burne-Jones’s work became more decorative as he became more aware of the abstract components of a painting such as colour and line. Although the narrative content of his work diminished he never allowed solely “aesthetic values” to become the total context for his art as it was to Whistler and Moore. In 1870 Burne-Jones resigned from the Old Water-Colour Society, which had been his primary artistic venue since 1864. Following his resignation he exhibited very little publicly and like Rossetti was dependent on the support of a few private patrons.

Left: Laus Veneris (In Praise of Venus) by Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones, Bt ARA. 1873-75. Oil on canvas, 47 x 71 inches. The Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle-upon-Tyne.. Right: The Golden Stairs by Burne-Jones. 1880. Oil on canvas, 269.2 x W 116.8 cm. Tate Britain Accession number N04005. Bequeathed by Lord Battersea 1924.

In the 1870s the direction of Burne-Jones is art changed once again and became increasingly influenced by Italian Renaissance art, but this time the emphasis shifted to Florence and Rome and away from Venice. As his technical competency increased Burne-Jones began to work on a much larger scale, and when his works were again exhibited to the general public at the opening of the Grosvenor Gallery in 1877 the development of his art in the intervening years created a sensation and he was immediately recognized as the leading artist of the Aesthetic Movement. Burne-Jones exhibited a series of masterpieces at the Grosvenor such as The Beguiling of Merlin and The Days of Creation in 1877, Laus Veneris and Le Chant d’Amourin 1878, and The Golden Stairs in 1880. Works like these established his reputation, not only in Britain, but also on the Continent.

Whistler, Moore, and Leighton as leaders of the Aesthetic Movement

Left: Symphony in White, No. 1: The White Girl. James Abbot McNeill Whistler (1834–1903). 1862. Oil on canvas, 213 x 107.9 cm (83 7/8 x 42 1/2 in.); framed: 244.2 x 136.5 x 8.3 cm (96 1/8 x 53 3/4 x 3 1/4 in.). Harris Whittemore Collection, National Gallery of Art, Washington. Accession No. 1943.6.2. Kindly made available as an Open Access image. Right: Harmony in Grey and Green: Portrait of Miss Cicely Alexander. James Abbot McNeill Whistler (1834–1903). 1873. Oil on canvas. 74 ¾ x 38 ½ inches (190 x 98). Collection: Courtesy Tate Britain N04622. Bequeathed by W.C. Alexander 1932.

Two other artists to emerge from the opening of the Grosvenor Gallery as leaders of the Aesthetic Movement were Whistler and Moore. Whistler‘s Symphony and White: No. 1 [The White Girl] of 1862 had been rejected by both the Royal Academy and the Paris Salon, but it was the succes de scandale at the famous Salon des Refusés of 1863, more so than even Edouard Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur L'Herbe. Even at this early stage in his career Whistler obviously intended this work purely as an exercise in exploring formal pictorial values in order to create pure visual beauty and he rejected any narrative meaning for his painting. Whistler’s works from 1864, including Purple and Rose: The Lange Leizen of the Six Marks, Rose and Silver: La Princess du pays de la Porcelaine, and Caprice in Purple and Gold: the Golden Screen show the influence of Rossetti and his circle. Despite their overt Japonisme Whistler used Japanese accessories in these paintings not only for their aesthetic value but to create an exotic appeal, much as Rossetti used a green Japanese kimono for the central figure of the bride in The Beloved of 1865-66.

In 1865 Whistler fell under a new influence, that of classical Greece, when he saw Moore‘s The Marble Seat exhibited at the Royal Academy. By that time Moore was already moving towards his mature style, concerned only with the colour relationships and decorative patterns that were to occupy him for the rest of his life. The Marble Seat is without any narrative content and is purely a harmony of tone and colour. Even by 1865, based on their exhibited works at the Royal Academy, Whistler’s Symphony and White: No. 2 [The Little White Girl] and Moore’s The Marble Seat, it was obvious that Whistler and Moore were moving in the same direction towards subjectless abstract compositions, concerned largely with decorative figure arrangements and colour harmonies. Whistler immediately struck up a friendship with Moore and the consequences of the collaboration between them was that Whistler appropriated those elements of Moore’s classicism that appealed to him, while Moore became influenced by Japanese art so that his palette became lighter in colour and he became more concerned with overall decorative patterns and effects. Moore’s paintings Sea-Gulls and Shells later brought him into conflict Whistler who was concerned these works would put his similar paintings for the so-called Six Projects in the light of imitation. This was not a prospect Whistler, who prided himself on originality, could countenance. Whistler asked Moore whether “we may each paint our picture without harming each other in the opinion of those who do not understand us and might be our natural enemies. Or more clearly if after you have painted yours whether I may still paint mine without suffering” (Asleson, Moore, 119-20). Whistler asked their mutual friend, the architect William Eden Nesfield, to arbitrate. Nesfield reported to Whistler on September 19, 1870:

I strongly feel that you have seen and felt Moore’s specialite in his female figures, method of clothing them and use of coloured muslin also his hard study of Greek work. Then Moore has thoroughly appreciated and felt your mastery of painting in a light key…In answer to your question ‘could each paint the two pictures without harming each other in the opinion of those who do not understand both’ I am quite certain you both may. The effect and treatment are so very wide apart, that there can be no danger from the vulgar fact of there being shore, sea, and sky and a young woman walking in the foreground. [Asleson, 120]

Whistler soon abandoned attempting large paintings of classically draped female figures, however, either because they were beyond his technical capabilities or to maintain his individuality from Moore. In the 1870s Whistler therefore turned instead to the subjects that were to become his chief contribution to the Aesthetic Movement - his nocturnes and his formal portrait arrangements. These allowed him to take full advantage of his natural ability as a colorist, and for subtle compositional arrangements exhibiting simplicity and economy of expression.

Moore was perhaps Aestheticism’s painter par excellence. In Swinburne’s Notes of Some Pictures of 1868 he comments on Moore’s Azaleas: “His painting is to artists what the verse of Théophile Gautier is to poets; the faultless and secure expression of an exclusive worship of things formally beautiful…The melody of colour, the symphony of form is complete: one more beautiful thing is achieved, one more delight is born into the world; and its meaning is beauty; and its reason for being is to be” (32).

Left: Azeleas. Albert Joseph Moore, ARWS (1841-1893). 1868. Oil on canvas, 78 x 39 ½ inches (198.1 x 100.3 cm). Courtesy of Collection of the Dublin City Gallery The Hugh Lane, registration no. 5. Right: Reading Aloud by Moore. Tempera or oil on canvas, 42 1/4 x 81 inches (107.3 x 205.7 cm). Collection of the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, Glasgow, accession no. 1218.

The narrative content in Moore's art is minimal and his art verges on the abstract. His classically draped figures are merely another element in the formation of a satisfactory composition with the same aesthetic values as any other object. Although his subject matter of classically draped women remained almost constant once his mature style had evolved, it served only as a theme upon which he could introduce slight variations in form and constantly impose new schemes of colour.

The Marble Seat by Moore. 1865. Oil on canvas, 18 ½ x 29 ⅜ inches (47 X 74.6 cm). Private collection.

By the mid1870s Moore's mature style had evolved, and it continued basically unchanged until his death. Paintings from his mature period consist of two main types, either single standing female figures painted on narrow upright canvases like Azeleas or frieze-like groups of three or four female figures like Dreamers or Reading Aloud.

Idyll by Frederic Leighton. Idyll. c.1880-81. Oil on canvas, 40 ⅞ x 83 ½ inches (104.1 x 212.1 cm). private collection.

Despite later being very much an establishment figure, Frederic Leighton made significant contributions to Aestheticism. Between his return to England in 1859, and his election as an associate of the Royal Academy in 1864, Leighton was very much an outsider and closely aligned with younger more independent artists like Rossetti, Burne-Jones, Moore, Whistler, Poynter, and Watts. Even early in his career Leighton’s affinity with the Aesthetic Movement was obvious. In the 1860s he begin to paint classical subjects, which brought him within the main stream of the movement. In 1861 he exhibited Lieder ohne Worte (Songs without Words) at the Royal Academy, the first of his paintings to convey a wistful mood through the use of a languorous full-length female figure.

Left: Lieder ohne Worte. Leighton. 1861. Oil on canvas, 40 x 24 ¾ inches (101.6 x 62.9 cm). Collection of Tate Britain, reference no. T03053. Right: La Pavonia. Leighton. 1858-59. Oil on canvas, 20 ⅞ x 16 ⅜inches (53 x 41.5 cm). Private collection

In the mid to late 1860s Leighton began to paint Aesthetic Classical subjects, as distinct from his earlier classical subjects based on mythology or ancient history that he had exhibited at the Royal Academy, such as Orpheus and Eurydice in 1864, and Helen of Troy in 1865. In 1867 Leighton exhibited Greek Girl Dancing at the Royal Academy, a moonlight scene that features a classically draped woman dancing on the left, with three seated spectators to the right, clapping to music. Richard Ormond has noted that Greek Girl Dancing is one of several of Leighton's paintings exhibited in the late 1860s that exemplify the decorative aspect of his art: "The figure of the dancer is balanced by a group of three spectators seated on a marble bench, who clap in unison. Through its repetitive forms (notice the patterns of the arms, and the four symmetrically placed rose-bushes), the composition expresses the rhythms of the dance through musical metaphors.

In this conjunction of art and music, the picture is close in spirit to contemporary paintings by Whistler and Moore, and represents the same Aesthetic impulse" (32). This painting was exhibited at the same Royal Academy exhibition as Moore’s A Musician and Whistler’s Symphony in White No. 3. All three paintings feature a similar flat, frieze-like composition. Many of Leighton’s most famous paintings feature classically draped females sleeping or in a state of reverie such as Odalisque, Mother and Child [Cherries] , Summer Moon, An Idyll, Cymon and Iphigenia, and Flaming June. His paintings featuring upright classically draped solitary standing females figures come very close to the work of his friend Moore, including The Bracelet, Crenaia The Nymph of the Dargle, and Nausicaa.

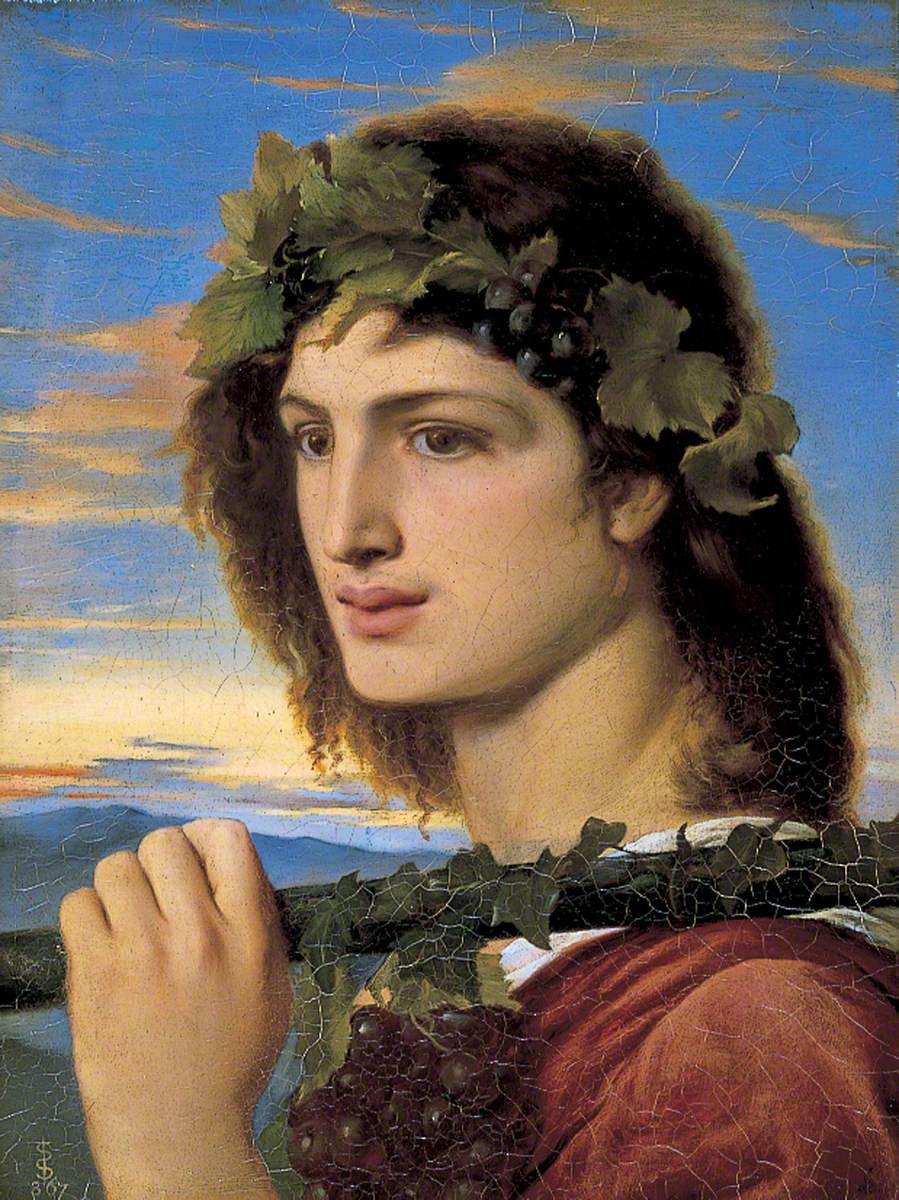

Left: Sappho and Erinna in a Garden at Mytilene.. Simeon Solomon (1840–1905). 1864. Watercolour on paper, 33 x 38.1 cm. Tate Britain. Purchased 1980. Right: Bacchus. Simeon Solomon. 1866. Oil on paper, 9 ⅞ x 14 ¾ inches (50.3 x 37.5 cm). Collection of Birmingham Museums Trust, accession no. 1961P52.

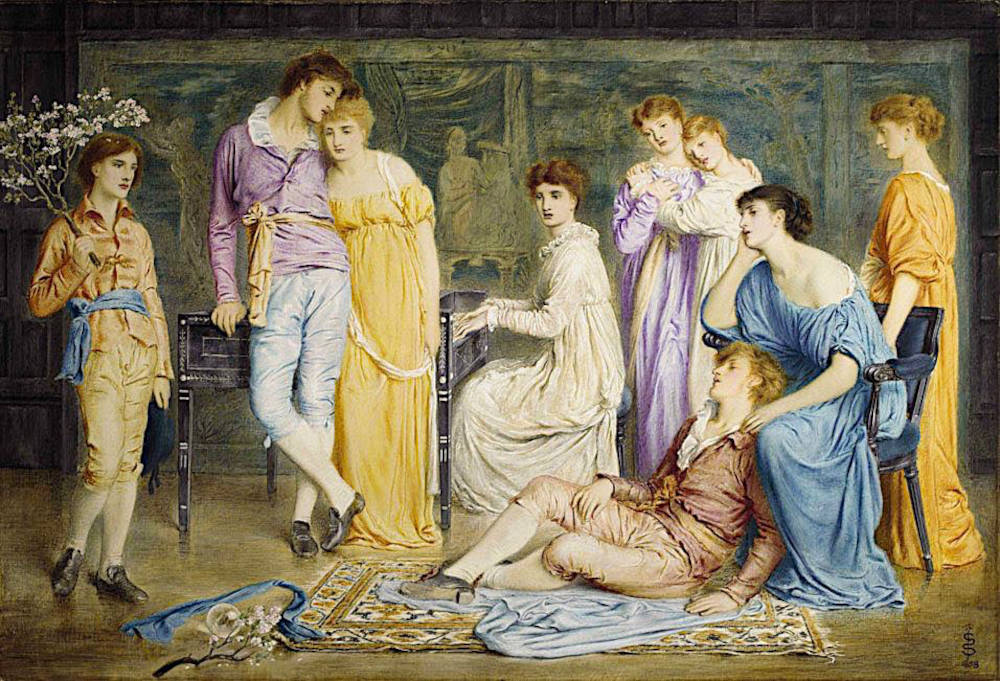

Simeon Solomon was one of the younger artists who made a significant contribution to the nascent Aesthetic Movement. While Solomon was a student at the Royal Academy schools in the late 1850s he formed a sketching club with fellow students like Holiday and Moore, both of whom would also later make major contributions to the Aesthetic Movement. After Solomon returned from his first trip to Rome in 1866 he began to paint classical subjects in an Aesthetic style. Like Burne-Jones his art had an enormous influence on the “Poetry Without Grammar School” that exhibited at the Dudley Gallery. As Ormond has noted: “His pictures are pagan and mysterious, hinting of perversities of thought and experience attractive to connoisseurs of the decadent” (27). Like Rossetti he painted pictures of stunners, but being gay his were frequently male, such as Love in Autumn of 1866, his half-length study of Bacchus of 1867, or his A Saint of the Eastern Church of 1867-68. His paintings of languid figures in a state of reverie included male in addition to, or instead of, female figures, such as in his A Song [A Prelude to Bach] of 1868. After 1873 his promising career disintegrated when he was charged with the homosexual offence of attempted sodomy. From this point onwards he stopped exhibiting publically and his influence on other artists waned.

A Song [A Prelude to Bach]. Simeon Solomon (1840-1905). Watercolor on paper, 16 ⅜ x 25 inches (41.6 x 63.5 cm). Private collection.

George Frederic Watts and the Reemergence of the Nude

Left: Thetis. Watts. 1868-69. Oil on canvas, 76 x 21 inches (193 x 53.3 cm). Collection of Watts Gallery, Compton, accession no. COMWG 42.Right: A Study with the Peacock’s Feather. Watts. 1865. Oil on canvas, 24 ½ x 20 ½ inches (62.2 x 52.1 cm). Private collection

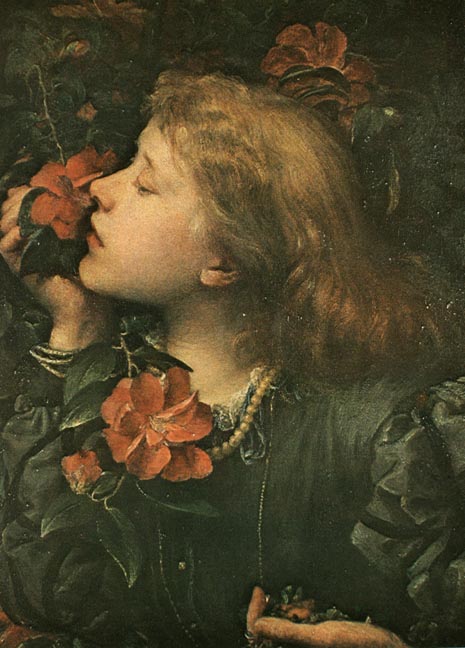

Watts is the last of the principal leaders of the Aesthetic Movement to be discussed. He was involved with the Aesthetic Movement for only a short period of time, primarily in the 1860s, before his art changed to the allegorical and symbolist works for which he is now best known. His work from the 1860s, when he fell under the influence of Rossetti and his circle, was also significantly different from what had come before. Watts played a key role in one of the most significant artistic developments of the 1860s - the reemergence of the nude. Watts first exhibited a female nude figure with no specific subject in 1865 that he had been working on since 1862, A Study with the Peacock’s Feather. This work was another hommage to Venetian Renaissance painting. Watts chose to exhibit this at the French Gallery rather than the Royal Academy so as not to risk offending Victorian sensibilities. He followed this up, however, with a full-length nude study called Thetis at the Royal Academy in 1866. Notwithstanding the classical title there are no references included in the picture to indicate it was anything more than a nude model by the sea. Despite prejudices against the nude being shown at the Royal Academy, Watts’s example was soon followed by Frederic Leighton’s Venus Disrobing for the Bath in 1867, Albert Moore’s A Venus in 1869, and Edward Poynter’s Andromeda in 1870.

In 1868 Watts showed a half-length painting of a semi-naked figure at the Royal Academy. Watts had based his The Wife of Pygmalion, A Translation from the Greek on a cast taken from the Arundel Marbles at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. The stony appearance of Galatea with her drapery derived from Greek prototypes led Swinburne in his Notes on the Royal Academy Exhibition, 1868 to interpret this painting as an example of synaesthesia defining it as the “’translation’ of a Greek statue into an English picture…how in the hands of a great artist painting and sculpture may become sister arts indeed, yet without invasion or confusion; how, without any forced alliance of form and colour, a picture may share the gracious grandeur of a statue, a statue may catch something of the subtle bloom of beauty proper to a picture” (31-32).

Two by Watts: Left: The Wife of Pygmalion. 1868. Oil on canvas, 26 ½ x 21 inches (67.3 x 53.3 cm). The Farington Collection Trust, Buscot Park, Oxfordshire. Right: Choosing. 1864. Oil on board, 18 ⅝ x 13 ⅞ inches (47.2 x 35.2 cm). Collection of the National Portrait Gallery, London, accession no. NPG 5048.1864

Alison Smith also felt this work represented a different form of correspondences than the more frequently portrayed examples showing a correspondence between painting and music: “In painting The Wife of Pygmalion, Watts set out to demonstrate the correspondence he believed existed between classical Greek sculpture and Venetian Renaissance painting. While the form possesses the solidity and restraint of the Phidian ideal, the subtle modulations of colour and the compositional formula bear hommage to Venetian painting” (cat. 129, 201). Watts painted similar half-length partially clothed female figures in the 1860s including The Wife of Pluto of c.1865-89 and his early version of Ariadne in Naxos of 1869. The Aesthetic Movement also had an impact on Watts’s portrait practice in the 1860s including his imaginative portraits of Bianca of c1860-62, Edith Villiers of 1861-62, his youthful bride Ellen Terry in Choosing of 1864, and of Blanche, Countess of Airlie of 1865-66. The latter two portraits, in particular, were heavily influenced by Venetian Renaissance prototypes and by Rossetti.

During the 1860s and 1870s Aesthetic Movement artists relied on venues like the Dudley Gallery to exhibit their works if they were not accepted by the Royal Academy. Even major artists like Burne-Jones, Solomon, Whistler, Moore, and Watts exhibited works there. In May 1877 the Grosvernor Gallery opened, an event that helped to make the Aesthetic Movement more popular than ever before with the British public. Up until this time many artists associated with the movement were largely dependent upon the private patronage of wealthy middle-class collectors who were primarily nouveau riche businessman and financiers such as a Frederick Leyland, William Graham, or George Rae. The Grosvenor Gallery featured the work of notable independent artist such as Burne-Jones, Whistler, Moore, Crane, Spencer Stanhope, and Holman Hunt. It also included works by prominent Royal Academicians such as Leighton, Poynter, Millais, Alma -Tadema, and Watts, although they mostly tended to exhibit more minor works and leave their major paintings for the Royal Academy. In 1887 the principal adherents of the Aesthetic Movement transferred their allegiance to the New Gallery. By the late 1880s Aestheticism had long ceased to be an avant-garde movement, although vestiges of its influence on British art could still be seen well into the early years of the 20th century. It was largely a spent force by the end of the First World War, however, as the horrors of the Great War and the advent of modernism had destroyed any thoughts of a search for an ideal beauty.

Bibliography

Asleson, Robyn. Albert Moore. London and New York: Phaidon Press, 2000.

Calloway, Stephen and Lynn Federle Orr, Eds. The Cult of Beauty. The Aesthetic Movement 1860-1900. London: V&A Publishing, 2011.

“Art, Craft, and Life. A Chat with Mr. William Morris.” The Daily Chronicle (October 9, 1893).

Gaunt, William. The Aesthetic Adventure. London: Jonathan Cape, 1945.

Ormond, Richard: "Leighton and his Contemporaries." Frederic Leighton. London: Royal Academy of Arts 1996, 21-40.

Pater, Walter. “The School of Giorgione.” The Renaissance. Studies in Art and Poetry. London: Macmillan and Co., Limited, 1917, 135-61.

Prettejohn, Elizabeth Ed. After the Pre-Raphaelites, Art and Aestheticism in Victorian England.. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1999.

Prettejohn, Elizabeth. Art for Art’s Sake. Aestheticism in Victorian Painting. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2007.

Rossetti, William Michael and Algernon Swinburne. Notes on the Royal Academy Exhibition, 1868. Part 2. London: John Camden Hotten, 1868.

Scheuller, Herbert. “Correspondences between music and the sister arts, according to eighteenth-century aesthetic theory.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 22 (1963): 334-59.

Smith, Alison Ed. Exposed. The Victorian Nude. London: Tate Publishing, 2001.

Staley, Alan. The New Painting of the 1860s. Between the Pre-Raphaelites and the Aesthetic Movement. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2011.

Stephens, Frederic George. Dante Gabriel Rossetti. London: Seeley and Co. Ltd., 1894.

Warner, Malcolm. “John Everett Millais’s Autumn Leaves: a picture full of beauty and without subject.” In Leslie Parris Ed. Pre-Raphaelite Papers. London: Tate Gallery Publications, 1984, 126-42.

Whistler, James McNeill. ”Ten O’Clock Lecture.”The Gentle Art of Making Enemies. London: William Heineman, Second Edition, 1892.

Wilton, Andrew and Robert Upstone, Eds. The Age of Rossetti, Burne-Jones & Watts. Symbolism in Britain 1860-1910. London: Tate Gallery Publishing, 1997.

Last modified 17 May 2022