This review is reproduced here by kind permission of the online inter-disciplinary journal Cercles, where it first appeared. The original text has been reformatted and illustrated for the Victorian Web by the author. [All images other than the first are from the sources specified, rather than the book under review. They can be used without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, provided you cite the photographer / source, and link your document to the Victorian Web or cite it in a print one. Click on the thumbnails for larger images and generally for more information about them.]

Nothing says more about the continual intersection of past and present than the Victorians’ fascination with the medieval. Here were people at the very hub of empire, in the midst of making the modern world, utterly beguiled by the distant past. Victorian artworks, architecture and poetry drew on it most obviously, with, for example, hundreds of new Gothic-style churches (or extensions to churches) springing up to cater to the spiritual needs of a growing population. But the attraction of the Middle Ages was felt across the cultural board. Charlotte Yonge’s novel, The Heir of Redclyffe (1853), held up chivalrous ideals to a whole generation of readers, while the more fun-loving enjoyed medieval bawdyism and trumpet fanfares at the music halls. Every aspect of the medieval had its adherents, including early church music, societies for which were founded at both Oxford and Cambridge Universities. Side by side with technological advance and empire-building went this constant retrieval and reworking of cultural capital, and, inevitably, it was both affected and spread by Britain’s wider reach into every corner of the globe.

Joanne Parker and Corinna Wagner’s introduction to the Oxford Handbook of Victorian Medievalism sets an unusually celebratory tone for such a weighty academic project, preparing readers to see the Victorians’ interest in this past not as a form of nostalgia, but as a means to promote “happiness, truth and beauty” (19). Parts I and II launch the handbook by dealing, respectively, with medievalism before 1750, and the medievalism of the Romantics. This is partly context, establishing lines of continuity to the nineteenth century. The revival of interest in ballads, and in the Gothic, provide useful background. Sir Walter Scott naturally features here, but philological studies and other topics also prove to be important. Also included is a chapter about the Diggers, the “communal experiment” of the mid- seventeenth century (77). Why? As Clare A. Simmons explains, the Diggers’ bid to assert farming rights over common land found its justification in the freedoms of pre-Norman times – and echoes of their campaign can be found as late as 1890, in William Morris’s News from Nowhere. “Morris’s combination of medievalism and communism clearly partakes of the Digger tradition,” says Simmons. “The Digger movement thus provides a significant bridge between the recreation of a vision of a historical medieval past and the dream of an earthly paradise” (81). This is just the sort of connection for which Parker and Wagner have prepared us.

A mosaic tribute to the Diggers in Cobham, Surrey, where the movement started (author's photograph).

In such ways, the early sections provide entries to, as well as contexts for, the later ones. Part III, on sources, is particularly illuminating. There is no proof that Morris actually read the work of Gerrard Winstanley, spokesman of the Diggers, but plenty of educated Victorians did read Chaucer and Boccaccio. No prizes for guessing that Chaucer’s sorely tried wife, the patient Griselda, was a particular favourite. But fewer people might recognise tributes to the Decameron: Eleanora Sasso has a revealing if sometimes challenging discussion of “Boccaccio’s Fiamatta in Rossetti’s Double Works of Art,” which explores the extraordinary richness of the Pre-Raphaelite artist’s vision. Sasso’s discussions of Morris and Swinburne in this part are equally informative, especially when it comes to Swinburne’s “perverted rewritings” of Boccaccio (262): not even the sunflower escapes this poet’s characteristic injection of pain. Irish, Welsh and Scottish backgrounds are also examined in this part, as are French and German trends. Elizabeth Emery and Janet T. Marquardt, for example, discuss “The Conservation Mentality: Vandalism, Preservation, and Restoration,” giving attention to such influential figures as the French architectural historian and restoration architect Viollet-le-Duc. Morris and Edward Burne-Jones viewed the French architect’s work on Notre Dame in Paris with dismay, and Morris’s feelings in particular would help to put a brake on insensitive restoration projects in Britain. As so often with exposure to the medieval, lessons were being learned.

Some stanzas of William James Linton's Bob Thin (available on Google as a free Ebook). The capital letters shown are F, O, O, W, D and A.

Medievalism also played a role in society at large: Part IV, on “Social, Political, and Religious Praxis,” examines the important ways in which it infiltrated movements like Young England Toryism and the Oxford Movement. Here as elsewhere, the Handbook presents some welcome reassessments, updating the scholarship in this area to good effect. Ian Haywood’s chapter on “Illuminating Propaganda: Radical Medievalism and Utopia in the Chartist Era,” for instance, puts the spotlight on William James Linton’s little-known anti-Poor Law poem, Bob Thin (1846), with its brilliant parodies of medieval illuminated letters. There are appropriate greyscale illustrations throughout, but, with good reason, this is one of the most fully illustrated pieces in the Handbook.

Such an enterprise requires a galaxy of scholars, and the next (and final) two parts, which range over arts, architecture and literature, bring together, for example, William Whyte on “Ecclesiastical Gothic Revivalism,” G. A. Bremner on “The Gothic Revival beyond Europe,” Jim Cheshire on “Victorian Medievalism and Secular Design,” Ayla Lepine on “The Pre-Raphaelites: Medievalism and Victorian Visual Culture” and Jan Marsh on “William Morris and Medievalism.” Their topics are the ones which most readers would expect to find in the Handbook, but there are still some surprises. Whyte, for example, provides a corrective to the familiar emphasis on “the” Gothic Revival of this period, concurring with recent opinion that Gothic had never really gone away. This, together with his Catholicism, might seem to diminish the importance of arch-Gothicist A. W. N. Pugin. But Pugin has already had some attention in Corrina Wagner’s chapter on “Bodies and Building: Materialist Medievalism” in Part IV, and, along with George Gilbert Scott and John Ruskin, Pugin receives more in Bremner’s lively chapter on the Gothic in British territories abroad. Whyte himself includes Pugin in his discussion of secular rather than ecclesiastical design. So he is not short-changed. On the contrary, what comes out here is the range of his influence. As the editors suggest at the beginning, it was remarkably pervasive, and not only geographically: “the very principles forwarded by Pugin motivated designers and collector to identify good design in Greek, Roman, or Renaissance styles” (13).

Left to right: (a) St Mary's Roman Catholic Cathedral, Sydney, by William Wardell, which Bremner calls "truly impressive ... on a scale comparable with that of an ancient European cathedral" (474). (b) Julia Cameron's photographic representation of King Arthur, for Tennyson's Idylls of the King. (c) Burne-Jone's depiction of Chaucer's Prioress's Tale, on a wardrobe for the Red House.

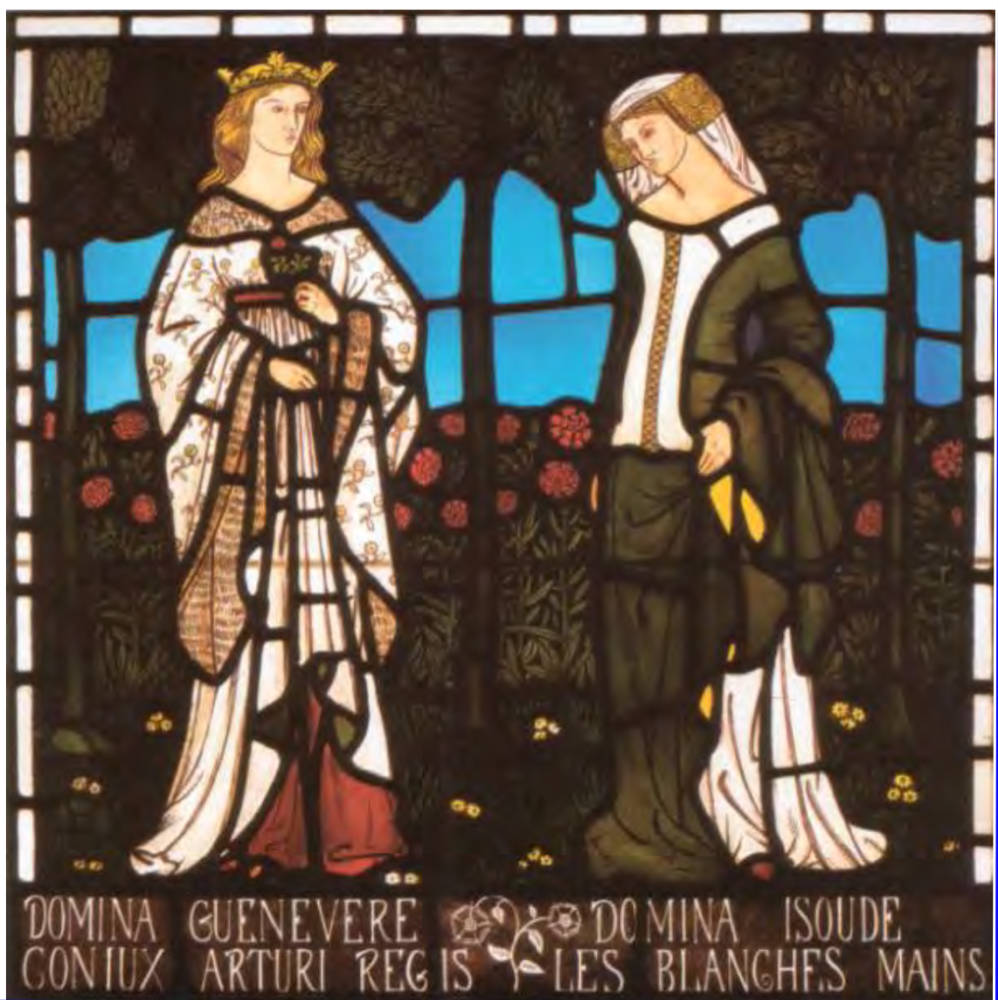

Similar correctives to or nuancing of conventional views can be found in Lepine’s chapter on “The Pre-Raphaelites: Visual Culture,” in which, for example, she includes the less-studied embroidery of the Morrises and Georgina and Edward Burne-Jones: the panels they designed for the Red House dining room depict characters from Chaucer’s Legend of Good Women (see p. 498). Lepine also briefly discusses Julia Margaret Cameron’s photography. After all, Cameron took photographs illustrating Tennyson’s Arthurian poetry. But women put in their most substantial appearance in Clare Broome Sanders’s “Women Writers and the Medieval” in Part VI. Here, the poets Felicia Hemans, Letitia Landon and Elizabeth Barrett Browning are among those discussed, and Sanders directs us to Judith Johnston’s George Eliot and the Discourses of Medievalism (2006), which sees Gwendolen Harleth in Daniel Deronda as a “disrupted Guinevere figure” (577). In this part too, Anthony H. Harrison takes up Tennyson’s Guinevere in the Idylls, and contrasts her with Morris’s in his “Defence of Guenevere,” showing how these authors all found scope in medieval legends to express the conflicting contemporary views of womanhood.

Stained glass depicting Guenevere and Isoude by William Morris, 1862.

Harrison’s “Mid-to-late Victorian Medievalist Poetry” in Part VI is complemented by Inga Bryden’s closing discussion of “Tennyson and the Return of King Arthur,” which establishes topical relevance in a different way. Bryden shows how Arthurian objects like his sword Excalibur help to recreate, substantiate and exoticize the medieval world, but at the same time embody the Victorians’ anxieties about their burgeoning material culture. On the one hand, “imitation ‘ancient’ objects, such as jewellery” were all the rage in Victorian Britain (657); on the other hand, how many times are swords shattered in Idylls of the King? Between them, therefore, the first and last chapters of the Handbook draw its rich contents together cleverly: Philip Schwyzer’s “King Arthur and the Tudor Dynasty” opens the proceedings with the eclipse of the historical Arthur, while Bryden closes them with proof of what Schwyzer affirms, the continuing relevance of the legendary Arthur. And, remembering the penultimate chapter here, Parker’s on “Anglo-Saxonism in the Victorian Novel,” with its remarks about the currently popular Netflix adaptations of Bernard Cornwall’s Saxon Stories (rechristened The Last Kingdom), we might extend that assertion to include medievalism in general.

Evelyn De Morgan's Flora (1894), inspired by Italian medieval altarpieces.

There are forty chapters here in all, counting the introduction — too many to mention in one short review. But, despite the Handbook’s enormous range, some readers might notice a few inadequacies. John Ruskin's appearances in it are not commensurate with his influence, despite Cheshire's conclusion, in his own short section on him, that it promoted the "kind of work ... strongly associated with medievalism" (453). Christina Rossetti is mentioned only in passing: Helsinger's point, that her poetry was influenced by the revived medieval liturgy, appears in a useful footnote (556, n. 2), but this has to send us outside the book for more information. Evelyn De Morgan, whose exquisite and well-known painting, Flora (1894), draws its inspiration and even method of composition from medieval Italian altarpieces, is not mentioned at all. De Morgan's later painting of a supplicating knight in anxious prayer, Our Lady of Peace, was inspired by the Boer War, but dated 1907, so comes too late for consideration here, but is further proof that medievalism remained and remains an intimate part of our cultural landscape.

Can we draw any general conclusions from all this? Although the book is pre-eminently a guide, a thesis does emerge. Writing about the Pre-Raphaelites, Helsinger explains that they “disrupted what they experienced as a stale present in both painting and poetry by returning to a primitivism of the visual, the musical and the poetic arts” (556). She adds later that bringing this past into the present opens a “productive gap” through which “something new might one day emerge” (566). As Parker and Wagner remind us so appositely in their introduction, the title of one of Morris’s essays is “How we live and how we might live” (18; emphasis added). The point is that medievalism is woven not only into our material and remembered past but also into our cultural and spiritual present, and that there is much there to stimulate change for the better. The past may feel like another country, but, if so, it is the one we inherited, and what we make of it and do with it will affect the future. We cannot be reminded of this too often.

Links to Related Material

Bibliography

Parker, Joanne, and Corinna Wagner, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Victorian Medievalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020. Hardcover. xx + 688 pp. ISBN 978-0-19-966950-9. £110.00

Created 22 February 2021