One day a man, not a navvy, went down to a dam asking for Mr Millwood. Nobody knew him. 'Hang it,' then said a stringy woman, taking a gum-bucket pipe from her mouth, 'tha means my feyther. Why didn't tha ask for Old Blackbird?'

It was part of a paradox: navvying was a community, but a community of strangers. People were isolated from each other partly by nicknames, partly perhaps because they were rarely sober, but mainly because they were so footloose. Theirs was a community in permanent flux, river-like in its constant flow. Men sometimes worked only an hour or so before drawing their pay and tramping on.

Well, I jacked at Stony Stratford and went on tramp. I had enough money to take a train to Nuneaton and I walked from there. Leicester, Barton, Derby, Matlnck, and up to Chatsworth. Went to work laying a pipe track from Derwent to Leicester. I didn't stop long and then I went on to Mexborough on the railway there. Trimming the> batters to make them look a bit decent, I lodged there with Big Arm Jack, a navvy.

After that I went to Penistone, over Woodhead into Manchester, on to Ramsbottom and Scout Moor. Worked on the puddle at Scout Moor, putting in> puddle clay. Two weeks there and we was froze out.

So winter come. Went away to Otiey. Froze out. Couldn 't work at Masham. Nothing for you but to walk. On to Lunedale. At Lunedale the gutter hadn't been sunk deep enough to stop the dam leaking. We drove seventy foot shafts down the sides, then drove a tunnel under the dam itself. They lowered concrete in skips and ran it under the dam in barrows. They were still winding the muck out of the hole when I got there. I says to Jack Petty, the gangerman; 'How are you fixed for miners?'

He says: 'Get agate tomorrow.' [8/9]

The isolation wasn't always broken even by marriage. Husbands went on tramp and were lost ;&mdash killed, crippled, too careless to bother. It the woman had no children it wasn't too bad. If she had, she was usually in trouble. It on top of that she were a hut-landlady, it was often worse. Only a man working on the dam could rent a hut. If the landlord left, the landlady had no rights to it at all. What she did have was the power to hand on the tenancy. She couldn't be queen in her own right but she could pick the king. When the timekeeper next called for the rent she had a few simple choices: the workhouse, skivvying in another woman's hut, or creating a new landlord from among her lodgers by inviting one of them into her big iron-bound bed.

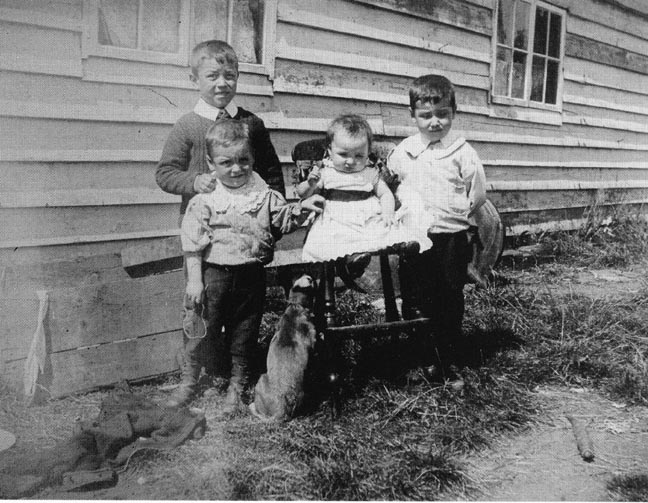

Navvy children, 1890s. Click on thumbnail for larger image.

In the middle of so much movement (and death) children were often handed along a line of foster-parents like small inheritances. Little Rainbow was the hero of one of Mrs Garnett's novels, but a boy taken from life. Boys like him were not uncommon on public works. His father was dead, his mother ran away, and he was brought up to the age of twelve by an old woman (until she died), by her widower (until he died), by Big Rainbow (until he went on tramp), and by Long Slen until Little Rainbow himself was killed by a wagon on the dam. The book opens with Little Rainbow dressed only in boots (too big), torn trousers and ragged coat. 'I'm cock o' this dock,' he boasted, challenging anybody roughly his size and weight.

Childhood in any case ended early. Pre-puberty boys often ran away, hidden on other works by nicknames. If they ever met their mothers when they were men they might shake hands in a restrained kind of way. Girls were often mothers, more rarely wives, in their teens.

Latter-day married navvies usually hauled their families and belongings about the country in railway wagons and furniture vans, but single men always tramped, sleeping rough in cowsheds, haystacks, hedges, kip-houses, pubs or using the workhouses like coaching inns, strolling from one to another in a leisurely sort of way. Navvies, along with sailors walking from port to port, were the casual wards' commonest inmates.

Similarities with the sea didn't end in the workhouse, either: navvying and the Navy paralleled each other in several ways, particularly public works and the 18th century gundeck. Both the sailor and the navvy were isolated, hard-worked, short-lived, and wild with it. Both lived dangerously but in the end monotonously. [9/10] When the larboard watch was ended, the day shift done, there was not a lot to do either in a frigate or on a dam except get drunk, and the navvy and the matelot met in a ready greed for drink. Rum and the sea ran together, like ale and earth. The images are harsh and salt-scoured: a gunner, his chin clipped away in battle, pouring rum down a speaking-trumpet into his stomach; Sailors tapping the cask carrying Nelson's corpse to drink the blood- thickened alcohol which pickled it. On public works it was whisky and ale. Buckets of it.

Buckets of it. You could wash your head in the buckets of beer we had. I wonder a feller wasn't ruined altogether. You come home half-lunified, get up stupid and go to work, work all day and stand up all night pouring beer down your neck.

In Scotland, where the drinking was harder, whisky was graded by the devastation it caused: Sudden Death, Fighting Stuff, Over-the-Wall, Pick-me-up, Knock-me-down. Sudden Death was nearly pure alcohol. One mid-century observer thought most navvies averaged thirty gallons of booze a week. Another thought a thousand pounds was spent on drink for every finished mile of track: twenty-five thousand pounds, perhaps, in today's money.

Even navvy society, unconventional as it was, had its own conformities, one of which was to drink. A society relying on its own generosity to itself has no place for personal meanness. Mean people were called 'near'.

'And you know, ma'am, to us navvies to be called near is as bad as murder almost,' a navvy once told Katie Miirsh, explaining how Red Neck Henry Hunns came to be drunk after taking up religion. Red Neck had been lured into a pub by two young navvies. 'Henry,' said one, 'treat us to a mug. You've grown rather near of late.' The publican, a mischief maker, gave him a mug of drugged ale. When he came round Red Neck was devastated. Almost unmanned. A massive dose of Bible-reading and self-recrimination helped, but in the end his misery was ended only by the cholera which killed him when his regiment, the Westminster Militia, was drafted to the Crimea.

I was lodging with Granny Tinsley at Llangyfellach the night the bog broke through and didn't 1 get some black looks from her when I went teetotal? It was a farthing a mile on the Great Western then [10/11] and I went up to London to my sister's wedding. When I got back I called her up and called for beer.

'I've broke teetotallmg, landlady.'

'I knew you would, my boy.'

She was a navvy person, but respectable. Some of them were.

'How is it you go back to your old ways so soon after leaving me?' a lady, the author of a book about navvies called Life or Death, once asked a navvy in the 18405.

'Well, ma'am,' said the navvy, 'it mostly comes of breaking the teetotal.'

'Why, then, do you break it?' 'Well, ma'am, it's only in a public or some low place a navvy can get lodgings and his tommy cooked: and the landlady won't say thank ye to cook your victuals for you if you don't have no beer. And when a chap's been keeping teetotal some time, the first pint is about sure to get into his head and make him want more, particular if it's public house beer.'

That drink was made easy to get, was one problem: grocers in bowler hats sold it from carts; wandering vendors carried casks of it — on yokes, like milk-maids-on to the works; most landladies sold it — it was almost the only way they could cope with high rents, bad debts, and the household bills — and neither big fines nor police raids could stop illegal liquor sales in the huts. [In 1889 the police raided the Moore settlernent on the Manchester Ship Canal in a furniture van. It stuck in mud. Navvies hauled it out. Unsportingly, the police went on to arrest four hutkeepers.] Either the drinkers swore the stuff was a free gift from a caring landlady or the police were shamelessly bribed with a bucket or two and sent home drunk as navvies.

'Another cause', said Mrs Garnett in 1881, 'is piece work. When a man says he has "made ten days in a week", who can wonder that being tired out, his pocket full of money, no fear of God nor respect for himself before his eyes, he goes and gets drunk? The first glass "picks him up", and if he ate a good beefsteak and two or three pounds of pudding with it, he would be all right, he would go and have a sleep and wake strong as a giant ready for "cricket" or the "tug of war". But, no! He turns from his lump of cold meat and cold pudding: for the landlady in a full drink selling hut has no time to make things nice, as she otherwise would, (and can get more [11/12] profit drawing beer to wash down cold tommy, than making you comfortable) so her lodger says, "another pint," and then "another", and then "one for Jack", "all round, landlady" is next; and when night comes — perhaps after a fight in which he has made himself look a brute instead of one of the finest Englishmen in the land — he snores in drunken sleep on his bed, every now and then muttering foul oaths, or lies sick as a dog under the summer sky, with God looking down on him; God who loves him, Christ who died for him! Think of it, brothers!'

When a man died there was, customarily, a gathering — a money collection — to bury him. What was left from the funeral was called the back-money and was spent on a wake. A ganger on the London-Birmingham railway once raffled a navvy's corpse, it was said, to raise money to drink to its demise. A fortnight later the parish had to bury the still unburied and now rotting navvy. Pre-1880, up to fifty pounds was sometimes spent on funeral parties. The drunker the mourners, the greater was the respect for the dead. One ganger is said to have jacked in protest at a teetotal funeral — it was, he growled, against all navvy custom.

In the 1830s (and perhaps earlier, but probably not much later) money collected to throw a welcoming party for newcomers was called a coking or a footing and was generally given by the newcomers themselves. On some jobs they saved the coltings till they had enough for a proper randy which always entailed a certain amount of riot, as Miss Tregelles found when she came on one unexpectedly in a South Wales village. Blackbird and The Miller were happily pounding each other while the police did their duty by keeping the natives out of harm's way.

'Are they fighting really, Sam?' Miss Tregelles asked a ganger.

'In course, ma'am,' said Sam. "Tain't no randy else.'

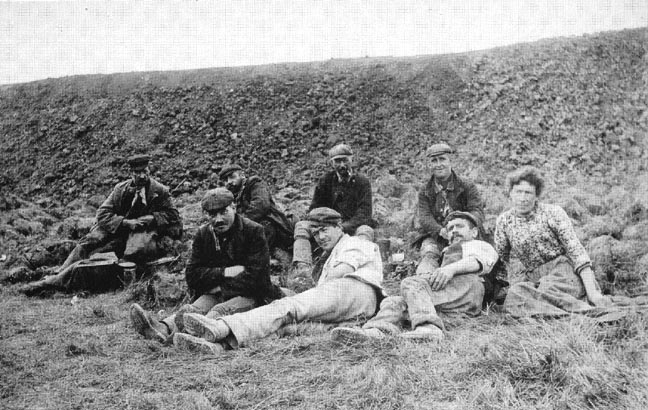

Navvy women, 1890s. The woman at the left wearing her Sunday best

looks quite expensively and stylishly dressed — certainly more so than,

say, a servant or factory worker.

[Click on thumbnails for larger images.]

Generally, women on public works are vague grey figures flitting into the printed record only every now and then, usually as insubstantial as souls in the Greek afterlife. Many who lived in the huts as 'servants', some of them very old, were prostitutes, while at least one contractor in Worcestershire in the 1840s or '50s ran a truck-brothel: women or girls in lieu of wages. Around the same time the asking price for the loan of a wife at the Summit tunnel, where syphilis was endemic, was a couple of pints of cheap ale.

But having said that, the abiding impression is that many, perhaps most, navvy women were extraordinary, more extraordinary than [12/13] their men. Many were as sober as their men were drunken. Their own rough respectability didn't always extend to marriage but cruelty to children was unheard of and an extraordinarily high percentage seem to have worked hard from early morning to late at night cooking, cleaning, washing, mending; sweeping and scrubbing huts inherently dirty, feeding gangs of men inherently hungry. 'I've known nothing but work and wickedness,' a navvy woman once rold Mrs Garnett.

Women got on to public works in two ways; either they were navvy-born, or they were seduced into following some passing, strapping buck-nawy, free, carefree, careless, and well-paid.

Navvy-born girls became small women when they were still very little. Mrs Garnett remembered one twelve-year old called Polly scrubbing the brick floor of her mother's hut one Saturday afternoon. Her lodgers got under her feet and she ordered them out.

"But, Polly, where are us to go?' they asked her.

'Go for a walk, it's Saturday afternoon.'

The big men ambled away, all except one who teased her by taking his time tieing his boots. Polly drove him out with a dish clout.

One day Anna Tregelles, who wrote about navvies on the South Wales railway in 1847, met two girls from Wiltshire. Both married navvies when the railway came to their village. Both wore the navvy dress of the time: black bonnets and bright ribbons, ear-rings, necklaces, short muslin frocks and thick leather boots. Caroline was older and more anxious, always fretting over the health of her children and mourning those who died. Sarah married Chimley Charlie in 1842 when she was sixteen. They had no children ('they're the ill-convanientest things that ever was to a navvy women,' she said).

At first Chimley was brutal, beating her with his belt until she knocked him down with a poker ('he come sich a bang,' she remembered, 'I thoft I'd a-killed en') after which he only hit her with his hands. 'Us was main comfortable for a year,' Sarah went on, 'and then 'twas winter time coming, and they was working nothing but muck. Charley was tipping then, like he is here: and 'tis dreadful hard to get the stuff out of the wagons when 'tis streaming wet atop and all stodge under.' The stodge ripped the soles off his boots, and they cost fifteen shillings a pair. In the end he could stand it no longer and took her on tramp into Yorkshire where he said the ground was all rocky and beautiful for tunnels. She'd never [13/14] been more than twenty miles from her Wiltshire village even know where Yorkshire was, but: "He took his kit, and I had my pillow strapped: o my back: and off us sot, jawing all along. Us walked thirty miles a day, dead on end: it never stopped raining, and I hadn't a dry thread on me night or day, for us slept in such miserable holes ot places, I was afeard my clothes'd be stole if I took them off.'

In Leeds she would never forget, not ever, the pleasure of a fire and supper in a pub. 'But,' she said of Leeds, "tis a filthy, smokey place and when I seen it by day, I says, well, if this is Yorkshire, us had better a-stopped where us was, dirt and all. And what a lingo they talk!'

And there was no work. They tramped another three days until Chimley got a start in a tunnel. "They was a rough lot there,' said Sarah, 'and then us seen and done all sorts o' things I wish I'd never heard on.'

They were a rough lot in Wales, as well, as she found when colliers from St Pagans challenged navvies to a Great Fight, or brawl, open to a dozen men a side but otherwise rule-free. Sarah heard about it from a navvy who ran up to her lodgings the evening of the Fight.

'Missus, they're fighting up to St Pagans,' he told her, 'and they've sarved your man very bad, and somebody's been and stole his clothes, so he can't get home.'

'I axed where he were,' Sarah told Miss Tregelles, 'and I up with his other shirt and slop and runned for my life to the place. There he was under the hedge, most dead with the cold; his things was all stole, and his money too.'

She half-carried him home and put him to bed where he stayed all Sunday. Monday morning he went to work but never came back. Sarah sat up all night, waiting, and at six o'clock next morning ran down to the line. Nobody had seen him. Perhaps he'd sloped, they said, on account of the fight; one Welshman was dead, two others were in a bad way, and the police were looking for navvies who'd been there.

Sarah traipsed all over Cardiff, town and docks, before she thought, 'He must have gone back into England.' In a pub a mile out of Cardiff she heard her first news of Chimley. He and two other navvies had stopped there, but only for a pint apiece. That night Sarah stayed with navvy people on the railway. Chimley had slept there the night before, they told her, and had gone on to [14/15] Sedbury where the line crosses the Wye at the Chepstow gorge into the deep rock cutting that ends abruptly at the crag's edge. (Sea birds swooped below the working navvies, close to the crinkled brown water.) Sarah followed in the morning. 'My shoes was all rags,' she told Miss Tregelles, 'and my feet a-bleeding every step.' But she found Chimley. 'Poor fellow, he were dead beat, sure 'nough.'

'But why,' asked Miss Tregelles, 'didn't he go to the police? The Welshman was killed at ten o'clock: Chimley was in bed by nine.'

'He couldn't. Miss,' said Sarah, shaking her head, quietly stitching pillow lace. "Tain't possible. They dodges so dreadful with their questions, there's no matching of them.' Besides, the Welsh had been worsted and that would have gone against Chimley with the Welsh police. Right or wrong, navvies got the blame. "Tis so bad, you know, to be clapped up in prison, and their hair don't hardly grow proper again tor a year, when they're out.' (So navvies wore their hair long as a mark of respectability.)

Welt, they were a bad set of buggers, there's no doubt about that, and it was a bloody dull sort of life any how, but it was a fraternity, was navvying.

Perhaps all societies which live hard, isolated, and uncertain lives tend to open-handedness among themselves. Navvies did. In away their hospitality was self-help at one remove &msah; you helped strangers because essentially you were a stranger in need of help yourself. Contractors like Peto relied on it and never subbed money to new men, who had to live for a week off their fellow-navvies. "There's a feeling amongst all those men exceedingly creditable to them', said Peto. 'Any man who comes there. And is at all in want, his brother navvies will take care he sh.i 1 hsv; plenty of tommy: they'll divide their dinner with him.'

Hospitality was even halt-ritualised in one or two 'ways of the line'. Men injured at work were entitled 10 help from their gang, Men on tramp were at least half-entitled to money from men in work. They called it the navvy's shilling.

From the Somerton tunnel I went to Ftshguard and started in the tunnel and lodged at Rosy Slen's shant. She sold beer. All these old landladies sold beer. Well, we were froze out at Fishguard and I went on tramp again. [15/16] Walked all day and all night. Had a mug of cocoa and bread in Gloucester Workhouse. It was crowded, and all. I had to sleep on the floor and then you had to wheel stones around for your keep.

Then I went to Winchcombe and got down on to the railway but there was no chance of a start. Devon Tommy gave me a shilling and Old Church and Greaseley Scan, the ganger, he gave me a shilling. That was the custom among navvies in them days. They called it the navvy's shilling, any how.

In effect the shilling was a crude kind of dole which worked as long as people kept up the payments and which lasted till the Great War. In no way was it token: a man could make as good a living scrounging as he could by working, though more often than not giver and getter got drunk as navvies and ended penniless together. Some non-working navvies (on canals they were often maimed men with names like Hoppity Rabbit and Dai Half) did offer the latest news and scandal for the shilling but others were little more than professional beggars in navvying clothing. 'Beware of William Grime, professional moucher,' the Letter warned of one such in 1900. 'He is an old soldier and has bad eyes. He shows a hospital eye ticket from Nottingham.' He'd begged on public works for twelve years calling himself a navvy though he'd navvied only once, for six months, in Hull.

'If you would not give them the shilling and the tommy,' said Mrs Garnett, 'we should soon see the last of these liars and thieves, who go about the country calling themselves navvies, and bringing disgrace on our honest name — for the kind people who are deceived by them do not know the difference between cadgers and real navvies, though you do and I do, and then we all get the blame — and no wonder.'

A cadger called Lincoln told Anna Tregelles his wife was ill. "She's a weakly body, and up in years, and we tramped from Gloucester, and are very bad off, my lady.' Their lodgings were a long way off, too far for Miss Tregelles to visit. But Miss T went anyway and found Mrs Lincoln dead drunk, swaddled in a coverlet like a mummy with a gin bottle. Miss Tregelles left no money — just a Bible, which Lincoln wanted to pawn, except his landlady wouldn't let him.

In the 1850s Katie Marsh knew of only one navvy-beggar: a gigantic, glib-tongued man who doctored a letter she wrote him (about his drinking) and used it to beg money from genuine navvies. [16/17] But after the 1880s sham-navvies — professional beggars - began swarming, battening on the navvy's generosity. Large moving bodies of navvies carried hordes of them, like lice: slow-moving, mis-shapen, fluttery with rags.

'We bring in a tremendous number of good-class navvies tor these public works,' the Chief Constable of Lanarkshire said in 1906, 'and they are followed by a regular horde of tramps who live on them. They are an absolute curse to the whole country. They come in and take away the character of these good-class labourers. People come and say: "We want extra policemen. We have navvies, and they are playing the mischief with the whole countryside". I say that the navvy is a poor, harmless person who gets drunk every Saturday like other people. It's these people who follow him who're the nuisance.'

Could the vagrants be dangerous?' he was asked.

'I don't think they have the pluck.'

"There's a good deal of exposure of person before decent people,' said the Chief Constable, 'but there is very little assault.'

Tramps following navvies to the Manchester Ship Canal were kept in specially rented warehouses. A few years later the Corwen Board of Guardians, plagued by beggars battening on men tramping to the Alwen dam, tried to get rid of them by making the workhouse even more loathsome than usual, mainly by increasing the weight of rocks casuals had to break and at the same time decreasing the mesh size of the riddles so they had to break the stones even smaller.

Yet begging was a navvy tradition, as well. They called it mooching. Usually they begged from door to door, rather than from people in the street, and they mooched food as much as money.

(Another time Old Hereford was in someplace in Yorkshire where they wouldn't give a navvy anything to eat. He took a brick up to one house. He says: 'Can you spread a bit of butter on this' The woman looks at him. He says: 'It'll go down better with a bit of butter.')

One day in 1906 Moleskin Joe, Patrick MacGill and a navvy called Carroty Dan left Burns's Model Lodging House in Greenock to tramp to the Blackwater dam at Kinlochleven. Since it was a [17/18] hundred miles away, Moleskin reckoned on a six day tramp and six days' mooching to keep them alive. Outside Greenock thev sol'i. Moleskin went ahead, followed by Carroty Dan, then MacCill.

'Whenever I manage to bum a bit of tucker from a house,' Moleskin told them, 'I'll put a white cross on the gatepost: and both of you can try your luck after me at the same place.' (A circle with a dot in its centre meant unfriendly police. The haft of a fork scratched in the dirt showed the best of two roads for mooching.) 'If you hear a hen making a noise in a bunch of brambles,' he told them in those free-range days, 'just look about there and see if you can pick up an egg or two. It would be natural for you. Carroty, to talk about your wife and young brats, when speaking to the woman of a house. You look miserable enough to have been married more than once. You're good looking, Flynn. Just put on your blarney to the young wenches and maybe they'll be good for the price of a drink for three.'

At the first white cross MacGill asked for a slice of bread. 'Don't give that fellow anything to eat,' a woman called from inside the house to the girl who answered the door. 'We're sick of the likes of him.'

'Poor thing,' the girl pitied him. 'He must eat just like ourselves.'

But MacGill was now too proud to take anything: he'd heard servant girls talk like that about pigs. He walked on until he came upon Carroty cuddling a withered whore by the roadside. She was blemished, aged by vice, yet it was a small comfort to MacGill that at least one woman took pleasure in a navvy. It was the last he ever saw of Carroty Dan.

He was turned away empty handed from two more white crosses before he met Moleskin again. Moleskin was milking a cow into a little tin drum he carried strapped to his leg. He filled MacGill's drum and they drank their milk and ate their mooched snap dappled sunlight by a beck. They took a dog-sleep in the sun and then crossed the Clyde in a stolen rowing boat, steering by the great crag of a rock with Dumbarton Castle on top.

Beyond Dumbarton they split again. Moleskin promising to [18/19] wait for him in the dusk along the Loch Lomond road. Now MacGill was luckier. An old lady gave him twopence, and his pockets were crammed with bread, his pipe with tobacco. Along the road in the wild country he heard Moleskin ahead of him singing in the twilight:

Moleskin had a stolen hen. ('When you're on the road as long as I've been on it, you'll be as big a belly-thief as myself.') 'Now we've got to drum up,' said Moleskin, 'and get some supper before the dew falls.' They plucked the hen and washed it in a spring of clear water. Deer came down to drink in the moonlight as they baked the fowl in the fire's embers.Oh! Fare you well to the bricks and mortar!

And fare you well to the hod and lime!

For now I'm courting the ganger's daughter,

And soon I'll lift my lying time.

Next day Moleskin had an argument with a ploughman who refused them a chew of tobacco. 'I'm a decent man and I work hard,' claimed the ploughman, 'and hae no reason to gang about begging'.

'You're too damned decent,' said Moleskin. 'If you weren't, you'd give a man a plug of tobacco when he asked tor it in a friendly way, you Godforsaken, thran-faced bell-wether, you.'

'If you did your work well and take a job when you get one, you'd have tobacco of your own,' came back the decent man, unabashed. 'Forbye you would hae a hoose and a wife and a dinner ready for you when you went hame in the evening. As it is you're daundering aboot like a lost flea, too lazy to live and too atrard to die.'

'By Christ,' bellowed Moleskin, 'I wouldn't be in your shoes anyway. A man might as well expect an old sow to go up a tree.' backwards and whistle like a thrush as expect decency from a nipple-noddled ninny-hammer like you. If you were a man like me you wouldn't be tied to a woman's apron strings all your life. You work fifteen hours a day every day of your life,' Moleskin accused him. 'If you look at another woman your old crow goes for you. You bring up children who'll leave you when you need them most. Your wife will get old, her teeth will fall out, and her hair will get thin, until she becomes as bald as the sole of your foot. She'll get uglier until you loathe the sight of her, and find one day that you can't kiss her for the love of God. But all the time you'll have to stay [19-20] with her, growl at her, and nothing before both of you but the grave or the workhouse. If you are as clever a cadger as me why do you suffer all this?'

'Because,' said the ploughman, 'I'm a decent man.'

Next day Moleskin and MacGill stood above a great glen in the rain, tasting the dye from their caps as it washed down their cheeks.3 They spent the night in a field. 'It's a god's charity to have a shut gate between us and the world,' said Moleskin, pulling the gate shut. What they'd mooched had to last until the next night when they reached the Kingshouse, an old inn with dormer windows breaking out all over its grey slated roof, standing alone in the yellow ochre and heather-coloured wilderness between Rannoch Moor and Glen Coe.

Moleskin prised off his boots by the heels, then broke bare-footed into the inn's chicken coop (he always carried a steel bar for snapping off locks). He groped about in the restless darkness, among the roosting hens making small unhappy clucking noises, touched and grabbed a rooster and padded back to the road where the cock got away, flapping awkwardly, clattering his wings and crowing. Moleskin threw his boot but missed. The cock zig-zagged away. 'Holy Hell,' said Moleskin.

'Who's there?' a man called from the inn. A light went on, a window rattled up.

'Can you get hold of it?' Moleskin half-bellowed, sweating into his whiskers.

'I can't,' MacGill told him. 'It's a wonderful bird.'

'Wonderful damned fraud,' said Moleskin. 'Why didn't it die decent?'

MacGill caught the fowl by the neck and they made off, chased by the publican. Moleskin alternately clumping and padding, one foot booted, the other foot bare, up the smooth black trough of Glen Etive towards Glen Coe.

'If you come another step nearer,' Moleskin stopped and roared back at the publican in the blackness, 'I'll batter your head into jelly.'

The publican slunk away, unseen. [20/21]

3 MacGill mistakenly calls it Glen Coe. It might be the glen above I och Tul imilarly, perhaps misremembering, he calls the Kingshouse the King's Arms.

They plucked and roasted the rooster by a burn in the small hours of the morning. Dynamite crumped in ihe mountains above them. Navvies on the night shift blasting rock at Kinlochleven. 'There's a good time coming,' said Moleskin, picking on chicken bones. 'though we may never live to see it.'

Those good times, though, never did roll for the navvy, while the better times which had already arrived were doing the navvy's character no good at all, according to some. By Moleskin's day, things had been changing tor thirty years, both nationally and, for the navvy, domestically. Most people were at least semi-literate because of the Education Acts and every man could vote in Parliamentary and local elections. The navvy's railways, like draw-cords, gathered the country together, making it less parochial. Navvies changed the country, then the country changed the navvy, softening him, educating him, making him less wild.

Public works changed, too, and changed the navvy in the process. Contractors were bigger and more respectable. They paid their men regularly, in coin, every week, in pay offices, and not irregularly every month in pubs. They were not cheated (so much) and not made drunk before being paid. A lot of their work was now on docks and dams which were inherently more civilised than the mobile squalor of the railways — they lived in semi-settled villages, for one thing, with all the restraints of a half-settled life. The Navvy Mission was bent on loving them, if nobody else was, so the sharp feeling of being totally rejected was slightly blunted. The works themselves were more mechanised and if the navvy still shifted his twenty tons a day, at least he was now surrounded by better educated mechanics, less brutal than himself. Because of mechanisation, as well, navvies were relatively less well paid than in the hey-day of the railway mania when their image of unhuman wildness was last imprinted on the public mind. At the same time, many non-navvy people thought they'd lost some of their finer qualities, their compassion and unthinking generosity to each other. As early as 1887 Mrs Garnett thought their moral fibre was becoming unravelled. 'Now, friends,' she said that year, 'I dare say you won't like what I'm going to say, but it is the truth, and any old navvies will bear me out in saying, there is now not amongst the nets navvies the feeling of honour there was amongst the old ones years "go. It now seems the fashion on some Public Works to think when winter comes it is the immediate duty of all the ladies in the neighbourhood to give food and soup, and keep all those who [21/22] drank or tramped about in laziness in summer. I was with a lot of the old sort on Sunday, who would scorn to think such meanness, and on Monday I got a letter which told me "I look in vain for a typical navvy on this job — the navvy of today is learning pauperism.'"

But by 1911 even the police spoke more kindly of navvies. That year, as the work on the Chew Valley dam was wound down, the local police superintendent said the area would lose some of its most law-abiding citizens when the navvies left. A navvy had been a rare sight in the police dock.

In 1908 they even had official Government praise. It was when the Unemployed Workmen's Act, giving local unskilled labour preference on local public works, was distressing navvies all over the country. 'I say there is no man in the army of our industrials,' said John Bums, President of the Local Government Board, 'to whom we owe more than to the navvy, the mark of whose hands is seen in the Tunnel, the Reservoir, the Railway, and Public Works, that serve our transit, supply our water, and make England the healthiest country in the world.' He went further and asked all public men to 'have that fine, healthy, strong, and clean industrial figure, the British navvy, on the skyline of your foresight, your outlook, your sympathies.'

It was, however, all relative: a tendency, not a break. There was a blunting of prejudice against navvies, not an abandoning. Shop-keepers and trippers from Rhayader visiting the Elan valley dams at the beginning of the twentieth century could still peer into the navvies' bedrooms, exclaiming in amazement that they slept in beds. With sheets. Like people.

Well, I was on tramp in Gloucestershire when this farmyard savage stops me. He says, 'Are you a navvy? Only speaking countrified. He says, 'I'll give you sixpence if you show me your tail.' They thought navvies had tails, you see, like monkeys.

Sources

[Note: Full citations for works cited by the name of the author or a short title can be found in the bibliography.]

The Old Blackbird story is from Our Navvies, as are the stories of the deserted wives' two weeks grace, and the boys who ran away, and the early motherhood of girls. Little Rainbow is from Little Rainbow.

'Sudden Death' etc is from Our Navvies and Annual Meetings Speeches. Red Neck Hunns is from English Hearts. The man who said breaking the teetotal was the reason navvies relapsed is from Death or Life. That drink selling in huts was the only way to make a profit is from Our Navvies. Mrs Garnett said piecework caused heavy drinking in Quarterly Letter to Navvies 12, June 1881. Cokings are from Barrett. The furniture van raid is from Leech.

The truck-brothel is from Conder. What happened at the Summit is from Chadwick's Papers. The woman who knew nothing but work and wickedness and the story of Polly are from Our Navvies. Sarah and Chimley Charlie are from Ways of the Line, as is Miss Tregelles's brush with Lincoln and his wife.

Peto told the 1846 Committee about navvy hospitality. William Grime, moocher, is from Quarterly Letter to Men on Public Works 89, September 1900. Mrs Garnett's attack on the shilling is from Quarterly Letter to Navvies 9, September 1880.

Tramps and Lanarkshire's Chief Constable are from Minutes of Evidence Taken by the Departmental Committee on Vagrancy, Vol 2, Accounts and Papers Vol CIII, 1906 (British Library Official Publications). This is also the source of the story about the tramps' warehouse on the MSC. Corwen's tramp problem is from the Liverpool Echo 17 February 1912. How Moleskin and MacGill mooched their way to Kinlochleven is from Children of the Dead End.

Mrs Garnett said there was now less honour among them than formerly in Quarterly Letter to Navvies 37, September 1887. The improvement at Chew is from the 34th Annual Report, 1911-12. John Burns's speech in praise of navvies is from Quarterly Letter to Men on Public Works 122, December 1908.

Last modified 19 April 2006