'After every pay the streets were disfigured by loathsome pools of blood,' said the anonymous author of Life or Death, a schoolgirl when the London-Birmingham was built. 'More than once we have seen men lying, literally dead drunk under the market house, an old-fashioned edifice raised on pillars, with the pigs walking over them, themselves fitter in all respects for a sty than any human habitation. Hapless toads and frogs, even little kittens, were literally torn in pieces.'

'Certainly no men in all the world,' said Mrs Garnett, 'so improve their country as Navvies do England. Their work will last for ages, and if the world remains so long, people will come hundreds of years hence to look at and to wonder at what they have done.'

Navvies it was realised, even at the time, re-made old landscapes and re-shaped old societies. Most people approved (fewer, perhaps, approved of the new landscapes) but hardly anyone approved of the sub-human navvy himself:

Rattle his bones over the stones

He's only an old navvy who nobody owns.

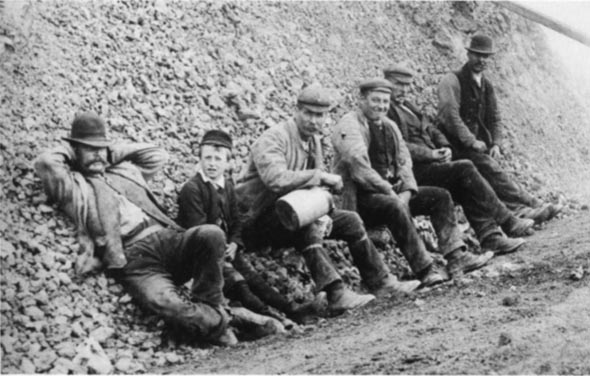

Navvies — the perpetual outsiders. Click on thumbnail for larger image.

He was a kind of un-man with earth in his pores, in muck-caked moleskin, lowering and aloof at the same time, always a by-stander, never belonging to the society he helped alter. He had a double impact: a purely contemporary one on the terrified people around him and a longer-lasting one, most obvious to anyone who rides a railway train or fills a kettle from a tap. The odd thing was so much fuss was made over, and so many changes were made by, few of them.

Between 1760 and 1830 just over four thousand miles of canal were made, though canal-making itself peaked in the 1790s (1792-3, more exactly) when over sixty waterways were authorised, started, [89/90] or finished — perhaps a thousand miles in ten years, a hundred miles a twelvemonth, on average.

In the 1790s it was supposed only twenty-five men were needed to dig a mile of canal in a year, although six hundred had laboured in the Harecastle tunnel alone; a hundred dug the approach cutting to the Greywell tunnel in 1788; a hundred and twenty-seven crowded into a single coffer dam at the Lune aqueduct in 1794; and three thousand shifted muck on the Grand Junction in Decemberember 1794, the year when the Worcester-Birmingham swore they'd hire no more than four hundred and twenty men on the three mile cut between Gas Street and Selly Oak.

Against that there seems to have been no more than eighty men on the whole of the Chester canal in May, 1773, while on many works only short sections at a time were cut by gangs of between twenty and forty men. Canals companies even tried to stop their cutters moving on. In 1767 the Staffs and Worcester published lists of runaways in the Birmingham papers. 'Johnathan Melloday of a brown complexion and squints with an eye and is about 5 ft 5 ins. John Catharall was 'Of a dark complexion, Pockmark'd, and has been a drummer 5 ft 7 ins.' Anybody who hired them would be sued. In May 1773 the Chesterfield committee ordered: 'That if any workmen shall run away and shall be brought back by Mr Varley, or any other person employed by him, that the expenses incurred thereby be deducted out of such Workmen's wages.' In July 1794, Philip Russell, Richard Glover and a navvy known only as Old Toby absconded from the Hereford and Gloucester and took work with William Thornbury, tree felling and cutting on the Gloucester and Berkeley. Within a week the Hereford and Gloucester invoked their agreement with the G&B not to hire each other's people and Thornbury was told to sack them. In Augustust, 1796, Gentleman Dick Jones, a contractor in the Netherton tunnel, was told to stop poaching men from the Worcester and Birmingham — it raised wages.

How effective it was is hard to say, but obviously there was no pool of tramp navvies working a few hours and a quarter of a day there as there was at the end of the next century.

If we take the 1790s, accept a hundred miles of canal were dug each year, accept the Worcester and Birmingham's hundred and forty men a mile as being average, accept that the contractor probably needed half as many men again because of drunken [90/91] absenteeism, add ten per cent for accidents, and accept that most were real navvies and not farm labourers, it is still hard to see how there could have been more than 20,000 to 25,000 professional canal diggers at any one time. By 1830 they may have dwindled to less than 10,000, though probably still more than 5,000 (in July 1827, sixteen hundred men were at work on the northern third of the Birmingham and Liverpool Junction, alone).

Roughly 50,000 men navvied on the first railways in the 183os. By 1846, 200,000 men were building railways and at least half must have been naw" 2,1 or labourers doing navvy-like work. In 1875 the Navvy Mission calculated there were around 40,000 nawymen out of a 60,000 navvy population, though probably those figures were too low: only fourteen years later they were talking of 90,000 navvy people all told. By the early twentieth century the Government itself thought there were between 100,000 and 120,000 navvies in the country. In 1909 the Royal Commission on the Poor Law put it as high as 170,000. (Not all worked at once. The Local Government Board once calculated a contractor needed a hundred navvies on his books to make sure he had fifty at work. The problem was subbing: men worked a couple of days, subbed their pay, got drunk.)

Wherever they went they impacted on unspoilt innocent landscapes like elemental forces, crashing out of a stillness, a hush, caused by expectation of their coming, bursting out like a train from a tunnel, all steam and fire, ferocity and danger. Once the early lines were laid, navvies came spilling in on the railways already built by their own people, cluttering up country railway stations (harassing rustic station masters), choking the highways with bird cages and baggage, prams, clocks, frying pans and bedsteads. Their impact on a tranquil rural population usually enlivened it, frequently debauched it, and always scandalised the ruling gentry. 'The females were corrupted, many of them,' said a contractor of the mid-Northamptonshire villages in the 183os, 'and went away with the men, and lived amongst them in habits that civilised language will scarcely allow a description of.'

The 1846 Committee was particularly worried. What if the marauding habits of the navvy lingered on, endemically, and damaged forever the docility of the rustic labourer? The Deputy Clerk of the Peace for Dumfriesshire already despaired for the moral health of the community.

'In what way?' asked the Committee.

'In the drunkenness of the little boys and the going together of [91/92] men and women to live without marriage.'

Abandoned mistresses, he almost implied, littered the parish welfare system. Local lads were debauched by drinking, swearing, fighting, and tobacco: boys, said the Deputy, aghast, of twelve and fourteen. And they earned ten shillings a week carrying blunted picks to the blacksmith's shop for sharpening.

And the Queen's peace?

'On pay days,' replied the Deputy, 'I should say the place is quite uninhabitable.'

Poaching bothered landowners just as much. Navvies were good at it (best in the world, they boasted) and since they roamed about in gangs nobody dared catch them.

When he first went to Blisworth on the London-Birmingham, Robert Rawlinson, the contractor, counted fifty hares in a single walk across Sir William Wake's estate. The day the first train ran. Sir William gave him a brace of partridge.

'I'd have brought you a hare,' said the disconsolate Sir William, 'but I don't believe I have one on my estate.'

'There isn't above one,' a navvy later told Rawlinson, 'and we'll have that this week.'

In 1881 Gaffer Brown, a navvy on Swansea Docks, was shot dead while poaching in South Wales. Next year a Mr Magniac was disturbed by the amount of navvy poaching in Bedfordshire. Bands of men with guns and dogs openly poached game, and assaulted the clergy. (He did admit the men lived badly, camped as they were by a swamp of slimy green water.)

At the same time navvies were money to rough country publicans and smarming shopkeepers. A Northamptonshire butcher, on the London-Birmingham, expected to sell the navvies thirty sheep, at twenty shillings a carcase profit, and a couple of bullocks every Saturday. Navvies complained he added bones as make-weights, but the other country butchers were so scared of them he'd cornered the entire navvy meat market.

In the 1870s the Rev Daniel Barrett was on the Kettering and Manton railway when the navvies arrived. Single navvies came on foot, navvies with belongings on every train, swarming into a string of instant shanty towns along the whole line. Some huts were sod. Some brick. Most were of wood. There were settlements opposite Chater viaduct, at Wing crossroads, on Glaston hillside. A settlement called Cyprus was on Seaton Hill. Another was in the Welland valley where the big viaduct crosses into the ironstone hills of Rutland. There were settlements near Gretton, at Penn Green, [92/93] Thorny Lane, Harper's Brook and Rushton crossroads.

Behind the navvies came the tradesmen, raising prices as they went, in drays and dog carts, pushing hand barrows: fishmongers, likeness-makers, book hawkers, packmen, cheapjacks, hucksters, milkmen, shoemakers, tailors. In a year the four thousand navvy people who lived there ate three thousand sheep, fifteen hundred pigs and six hundred oxen.

The impact of what the navvies did, the work they left behind, was always more appreciated than the navvy, yet in the bad weather of 1881 a few members of the Hope, near Oldham, Juvenile Christian Temperance Society rode through snowdrifts in a large wagonette to entertain navvies at the Denshaw dam, the way dimly lit by snowlight shining off the moors as they rounded the bend from Denshaw village. Joseph Burgess wrote — and read aloud — a poem:

They are the Denshaw navvy boys

and I extol them thus

Because our town great good enjoys

Such men have wrought for us.If you have ever fetched a burn

from an asthmatic pump

And waited, starving, for your turn

till nearly stiff with cramp,If you with water on your head

and ice beneath your feet

In making an incautious tread

have fallen in the streetIf you've been drenched from top to toe —

a not uncommon plight —

You'll feel with me how much we owe

The men we've met tonight.

But it was easy to enthuse about dams: they were small and hidden, scarring only small landscapes, their benefits obvious at the turn of a tap. The railway was harder to like and the Kendal and Windermere, in particular, upset> Wordsworth:

Is there no nook of English ground, he asked, secure

From rash assault? [93/94]

'Now, every fool in Buxton can be in Bakewell in half an hour,' said> Ruskin, 'and every fool in Bakewell in Buxton.'

But railway speculators and navvies between them ruined things for many a man more humble than Ruskin or innocent than Wordsworth. The Rev Armstrong's family bought a cottage in Southall not long before the Great Western went there, while he was still in frocks. He had his own garden to cultivate, a gate to swing on, a canal to fish in in all innocence. Then came the navvies like corruption. 'The railway spread dissatisfaction and immorality among the poor,' said the Rev Armstrong, 'the place being inundated with worthless and overpaid navigators ("navvies").' 'The rusticity of the village gave place to a London-out-of-town character,' he went on, getting closer to what really upset him. 'Moss-grown cottages retired before new ones with bright red tiles, picturesque hedgerows were succeeded by prim iron railings, and the village inn, once a pretty cottage with a swinging sign, is transmogrified to the "Railway Tavern" with an intimation gaudily set forth that "London porter" and other luxuries hitherto unknown to the aborigines were to be procured within.'

Around the same time,> Dickens saw the London-Birmingham's impact on Euston and Camden Town quite differently. The works themselves were like an unnatural disaster area; a primeval place, pre-fern forests, pre-fishes, still hot and steaming; there were mouldering rusty ponds, crazy shored up houses and lifeless heaps of lumpy earth. Only a few speculators nosed about the site. One or two streets had been half-started in the muck and ashes but what buildings there were — a pub, eating house, lodging houses — were there to exploit the navvy. For the rest there were:

frowsy fields, and cow houses, and dung-hills, and dust heaps, and ditches, and gardens, and summerhouses, and carpet-beating grounds, at the very door of the Railway. Little tumuli of oyster shells in the oyster season, and of lobster shells in the lobster season, and of broken crockery and faded cabbage leaves in all seasons.'[Dombey and Son]

But soon it too was as transmogrified as the Rev Armstrong's Southall, though not into something base and secondhand, but into stuccoed prosperity and fat warehousing. The railway ruled all. Even clocks kept railway time. What had been rotten and decayed was now alive and thriving. Even Members of Parliament dimly understood something important had happened.

For John Masefield, navvies both made and destroyed what he [94/95] prized: the Hereford and Gloucester canal. As a child he lived close to where the canal and the Great Western crossed each other oustide Ledbury. Not far from his home near the River Leddon was a canal port, a haven in both senses of the word — a dock and a peaceful place. But it was terror-stained, too: unwanted dogs were drowned where the railway bridged the canal. But, 'Beyond that bridge of drowned dogs for some quarter of a mile or more a lovely reach stretched to Heaven and the sun that shines in childhood. In memory that reach is always sunny, and at one point in it, about halfway along it, some lucky and happy boys were free to swim. The water in that reach seemed always to be clear: fish would rise and moorhens would paddle.' Sometimes he was allowed to take his fishing rod, to catch goldfish. Along the canal, too, was a hillock covered in every season with flowers.

Often the narrow boats were crewed by a man and his wife. She took the helm, her milkmaid's cap a-flapping, while the man — singing or knitting — walked ahead with the horse. It was Life perfected. To his boy's mind the boat people even had their own rollicking Sailor Town in dozing, semi-timbered Ledbury. Bye Street was their Tiger Bay where they caroused and got merry.

In the 1880s another generation of navvies destroyed the canal by building a railway. For years, men mourned the old canal and its quiet places. Now the railway's gone, too.

Into many small communities navvies intruded only briefly. They came, amazed, and went. Behind them they left a slowly blossoming change. Red brick towns grew along the vein of their track.

Until 1869 Winchmore Hill was a small hilltop village ten miles from London, off the main highway on the outskirts of Enfield Chase, overlooking the Lea valley marshes. London was two hours away by a yellow mail coach called Little Wonder which made the journey twice daily, setting off from the Flower Pot Inn in Bishopsgate, through Tottenham village, past the elm trees they called The Seven Sisters. Years later Henrietta Cresswell, the doctor's daughter, wrote a bazaar book about the village and the coming of the railway to Winchmore Hill. The hill she remembered was as bright and fresh as toddling childhood; a blend of clarity and colour, like a mix of paint and transparency. Even the air seemed brightly painted. It was like a land of long ago. What is now north London was then all rickyards and honeysuckle, wild hops, wild roses, thickset hedges [95/96] and forget-me-nots. The village pond was padded thick with water lilies and the New River brimmed with fishes, silver bleak and chub, miller's thumb and gudgeon. Noises were clearer and sharper: grunt of hedgehog, bleat of sheep, low soft low of cows. Corncrake. Whirr of cockchafer. Hunting owls, soft as feathers, nightingales in the woods when dusk clung to the eyes like cobwebs.

Memories were fewer, but richer: the summer the hailstones killed cattle in the meadow, flailed trees to death; a Photographic Establishment in a brown van which pitched one summer on the green, taking grey-green positives on glass; the cow-slow evening when a villager rode home on a velicopede with wood wheels; the year of the comet which Miss Cresswell saw in the dusk of another summer's evening, the sky all amber and blue, a grey mist in the willows by the river; straw hives, bistre to ochre, under the eaves; bees swarming in May; drowsily bee-watching, lolling in a wheelbarrow, lulled by the insect-humming garden; following the swarm across meadows in the honey-gold sunshine, tang-tanging a bell to tell the neighbours to shut their windows.

Navvies came to this golden hill in the hot summer of '69, tearing down houses and putting up huts, grubbing up holly hedges and ash trees. 'The excavation was beautiful in colour,' said Miss Cresswell, who clearly saw with a painter's eye,

the London clay being a bright cobalt blue when first cut through, and changing from exposure to orange. There were strata of black and white flints and yellow gravel. The men's white slops and the red heaps of burnt ballast made vivid effects of light and shade and colour against the cloudless sky of that excessively hot summer. There were also dark wooden planks and shorings to add neutral tints, and when the engine came the glitter of brass and clouds of white steam were added to the landscape. On Sundays and holidays the men were, many of them, resplendent in scarlet and yellow or blue plush waistcoats and knee breeches.

After the hot summer came the deep snow of Januaryuary and her house was abandoned to the works. Shrubs in her abandoned but unneglected garden slipped over the edge of the cutting and were retrieved and re-rooted time and time again. Part of the wall was rebuilt but frost got into the mortar and it fell down again. Then navvies began using the garden as a thoroughfare.

There had been much fear in the village of annoyance from the horde of Yorkshire and Lincolnshire railwaymen brought into the [96/97] village by Firbank, the contractor, but on the whole their conduct was very orderly, and they can hardly be sufficiently commended for their behaviour. A noticeable figure was "Dandy" ganger, a big north countryman, decorated with many large mother of pearl buttons and a big silver watch chain. He instantly checked all bad language in the neighbourhood of the Doctor's garden. Many of the navvies brought their food or their tea cans to be heated on the great kitchen range, and never once made themselves objectionable.

The railway should have been ready by 1870, the date on the bridge by Winchmore Hill station, but the wetness of the local clay held it up. The previous year's drought misled the engineers into miscalculating how much water there was in the shallow valley they were crossing on embankments and short viaducts. One of the viaducts cracked when the blue slipper clay sank, and the line sloped up and down ever after. Long after the track was open, the slip slowed the up-line trains. So the navvies stayed on through 1870 and into the next Spring. Five men died on the five mile track, more were gassed to death by fumes from the heaps of burning ballast where they slept, until the dying on that particular line stopped on April Fool's Day 1871, when it was officially opened to the the crack of fog-signals and the noise of navvies. Soon passenger trains, all hot oil and coal smoke, quickened the village into a London suburb.

The old isolated eccentricity of rural England was soon gone. Today Winchmore Hill is a thoroughly respectable, uneccentric place, trenched in two by the railway and sewn together again by bridges. The embankment is now part of the townscape, thick with mature trees. Of the buildings of Miss Cresswell's day few remain: the Friends' Meeting House, perhaps, and the Old Bakery. [97/98]

Sources

[Note: Full citations for works cited by the name of the author or a short title can be found in the bibliography.]

The London-Birmingham men who tore kittens apart are from Death or Life. Mrs Garnett stated her conviction that nobody so improved their country as navvies in Quarterly Letter to Navvies 5, September 1879. "Rattle his Bones" is from Quarterly Letter to Men on Public Works July 1931.

The numbers of men working on various jobs are from printed sources, except the Worcester and Birmingham-PRO RAIL 886/4 — and the Chester, PRO RAIL 816/2.

The description of runaway navvies from the Staffs and Worcester is from Hanson's Canal People where the source is given as Aris's Birmingham Gazette 1 June 1767. The Chesterfield's dictat is from PRO RAIL 817/1. What happened to Hereford and Gloucester absconders is from PRO RAIL 836/3 and 829/3. Gentleman Dick's poaching is from PRO RAIL 886/4.

That 50,000 men built the earliest railways is from Redford. The 1870s' estimates (40,000) are from The Quiver, 3rd Series, Vol 12, 1877. The 90,000 up-date is from the Wandsworth Observer 15 June 1889. The Local Government Board's figures are from Dr Reginald Ferrar's Report to the Local Government Board on the Accommodation of Navvies at the Brooklands Race Track, Parliamentary Papers Cd 5694 LXVIII 1907. The highest figure, 170,000, is from Evidence Before the Royal Commission on the Poor [247/48] Law, already mentioned.

The tale of the corrupted females is from the 1846 Committee. Ward claimed navvies were the world's best poachers in his Justice article, already referred to. Sir William Wake's losses are from the 1846 Committee, as is the story of the Northamptonshire butcher. Gaffer Brown is from Quarterly Letter to Navvies 1, March 1881. The Bedfordshire poachers are from Our Navvies.

Burgess's poem is from the Oldham Chronicle 22 January 1881. Wordsworth's sonnet, On a Projected Kendal and Windermere Railway, is from his collected Works. Ruskin's quotation is from Works of John Ruskin, 1907. How the National Trust was founded is from B L Thompson's book The Lake District and the National Trust and Henry Fedden's The Continuing Purpose. The Rev Armstrong's lament is from R M Robbins — A Middlesex Diary, printed in the Transactions of the London and Middlesex Archaeological Society, X 1, 1954. Dickens wrote of the Camden Town in Dombey and Son. Masefield wrote of the Hereford and Gloucester in Grace Before Ploughing. What happened to Winchmore Hill is from Henrietta Cresswell.

Last modified 21 April 2006