'I have had the diarrhoea for a week but I am very well again, thank God for it,' Robert Bagshaw, navvy, wrote home from the Crimea. 'As you wish me to send all the news I can, I must tell you that Sebastopol is taken at last.'

Navvies, as navvies, worked for the Army in four wars: against Napoleon, where they helped dig the Royal Military Canal; the Crimea, where they were a bit of a triumph; the Sudan, where they were a bit of a disaster; the Great War.

Napoleon impinged on them mainly by causing a navvy shortage, though many were pressed or recruited into the armed forces as well. Wages rose. Costs doubled. 'As the soldiers will be disbanded on Saturday, I propose trying if I cannot get about twenty of them to carry up the cut,' said the Lancaster canal's secretary at the start of the Peace of Amiens, 1802. (Privateers also pillaged the canal's cargoes of pozzolana, the hydraulic ingredient in mortar, which came from Italy.)

In the summer of 1803, Hugh Macintosh, the muck-shifting contractor at Blackwall docks, was troubled by the Press Gang. 'I have within these few days,' he wrote to the East India Company, 'perceiv'd some Alarm amongst the Men employ'd on account of the Danger of being impressed, a Report being circulated of a number of hands being taken from the London Docks, and I beg leave to suggest the necessity, if it is practicable, of obtaining a Protection.' (Protections were certificates telling the Press Gang in unsteady type and quilled ink that the Bearer was exempt from naval service.)

Navvies were scarce. In the summer of 1804 Thomas Thatcher poached Kennet and Avon men to work on the Floating Harbour in Bristol. A few weeks later the Royal Military Canal poached the same people for war work. 'There now appears in a Bristol paper an advertisement for two thousand men to be employed in Kent,' Tom [142/143] Thatcher wrote in the Kentish Gazette in November. 'I hereby inform the workmen that it is my intention to give greater price for work than has or may be offered by any contractor for work of this kind in Kent.' ('And you won't have to walk five miles for your breakfast in Bristol,' he added.)

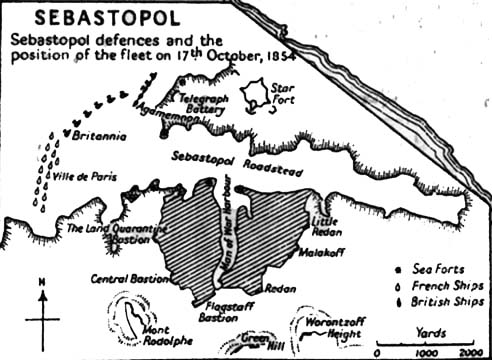

In the summer of 1802> Addington, the Prime Minister, laid the foundation stone of the London Dock, downstream of the Tower [ photograph]. The Chancellor of the Exchequer chucked a purse of gold on a stone for the men. A year later the company wrote in its report, 'The uncertain delivery of Materials, an impossibility of obtaining and keeping together a sufficient number of Workmen many of whom have been at times called off to National Works, and other circumstances unforeseen in an undertaking so extensive and unexampled have delayed completion of the Works.' The National Work, perhaps, was the Royal Military Canal, ringing a cam-shaped bit of Romney Marsh and intended primarily as an anti-invasion ditch, a lot of it built between 1804-9 by the Royal Staff Corps, the Royal Waggon Train, and infantrymen, as well as civilian navvies. Both the Royal Staff Corps, which did the Army's civil engineering, and the Royal Waggon Train, which hauled its freight, were disbanded before the> Crimean War, which essentially was the siege of Sebastopol, where engineering and logistics where the Army's big problems.

Maps of Sevastapool (left) and Inkerman (right). Click on thumbnails for larger image.

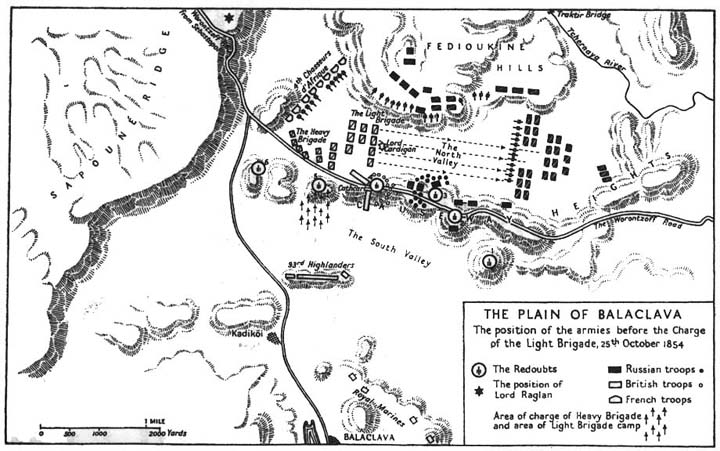

The French commander, Canrobet, asked Lord Raglan to choose a sea-base. Raglan asked Admiral Lyons. The Admiral chose Balaclava and gave the British Army the eastern end of the siege and two of the war's battles, Inkerman and Balaclava [photograph], both fought to stop the Russian field army breaking out of Sebastopol.The Allies lay in a semi-circle on the heights above Sebastopol, where the British Army was fed, munitioned, and carted (dead and dying) by ox-carts and pack-ponies along a track like a mud-filled ditch which joined the Balaclava naval base to the Woronzov Road, the only metalled highway on the peninsula. What was needed was a good road or a poor railway, but the Royal Staff Corps which might have made them was long disbanded. It was then that the civilian contractors Peto, Brassey and Betts made the country an offer it couldn't refuse: a military railway in the war zone at cost.

Map of Balaclava. Click on thumbnail for larger image.

Balaclava is hemmed in east and west by limestone hills. The western hills fall straight to the sea but to the east is a narrow coastal plain where Balaclava stands. In town, the harbour lay on both sides of a creek. Kadikoi, in the Balaclava valley, is about a mile inland, its [143/144] vineyards and poplar groves long denuded by the foraging army. At Kadikoi the valley turns west and runs for about a mile to the Flagstaff at the foot of the plateau on which the armies lay. Horse-drawn trains were to begin on both sides of the harbour, run along the valley to Kadikoi, turn with it to the Flagstaff and then be hauled by stationary steam engines on to the plateau; seven miles, almost, from sea to trenches.

Peto left Parliament to mastermind it, helped by brother-in-law Betts who was in charge of the ships. A recruiting office was opened early in December 1854, in the Waterloo Road and for a day or so three hundred navvies thronged about the place, signing on for five shillings a day, a soldier's rations, and a free passage there and back. Most were English, a few were Irish, and most worked either on the London, Tilbury and Southend Railway, in the Victoria Dock (image) , or on the Houses of Parliament (image). They were called, semi-officially, the Railway Construction Corps or the Civil Engineering Corps and were led by James Beatty, a railway engineer from Inniskillen. Apart from navvies there were drivers, carpenters, horsekeepers, well-sinkers, clerks, fitters, sawyers, a draughtsman, a barber, a surveyor and his chain lad, a cashier, timekeeper, storekeeper, and two missionaries, the Rev. Thomas Fayers and the Rev Cyngle, who built a church. For their health they had a set of nurses, possibly Gamp-like, Mrs Fapp, Mrs Prestige, Mrs Williams, and Mrs Duffield.

Recruiting the Navvies — "Mssrs. Peto, Brassey, and Betts, Waterloo-Road.".

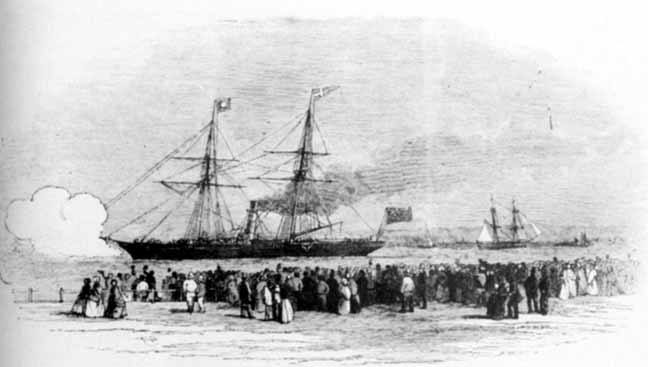

Prince of Wales Steam-Ship Leaving Blackwall with Navvies for the Crimea. Click on images to enlarge them.

They went in a fleet of twenty-two ships, steamers and sailers, each so laden her loss at sea wouldn't wreck the entire enterprise. Between them they carried all the rails and sleepers, all the wagons, barrows, tools, forges, cranes and pile drivers. Hesperus was still building in Mitchell's Walker-on-Tyne yard, next to the ironworks where the railway's rails were forged. They were loaded hot from the furnace into her unfinished hold. Shipwrights worked around the clock getting berths ready. There were little hundred horse steamers like Propellor, Lady Alice Lamhton, Baron Von Humboldt, and Prince of Wales. Paddlers like Levant and sailing ships like Mohawk and Wildfire which in Balaclava doubled as hospitals.

Wildfire sailed first, dropping down the Mersey early in December. Her navvies mustered at Euston Square Station (contemporary illustration), filling in allowance papers for wives and relatives, before travelling by train to Liverpool (contemporary illustration). Stay-at-homes cheered them down the river, emigrants huzzaed them. For the navvies it was a well-paid lark all [144/145] the way. They stormed the Rock of Gibraltar and in Malta they held boxing matches to finance a randy after they were let ashore without money.

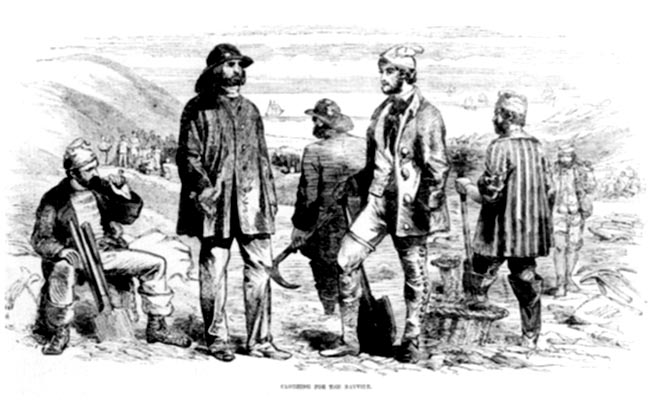

Eight weeks, almost to the day, after the 'no more men wanted' notice was nailed to the recruiting office door in Waterloo, navvies sat and growled, cooped in their ships in Balaclava harbour waiting for the weather to clear. One night there was a pitched fight in the holds. Outside frost and February cold ripped flesh from men's bones. When they emerged, earthy creatures creeping off the sea, they astonished the Army. Unutterable things, an officer called them, whose nature it was to work upon railways — as though railway-making were encoded in their genes. They strode about, saluting passing soldiers, caped like cabmen, the peaks of their caps hanging over the napes of their necks like coal-heavers, clay-piped and cocky, prideful as became men out to do a job nobody else could do.

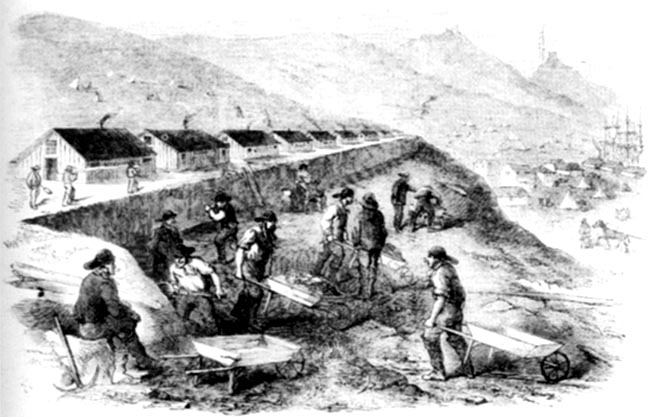

The huts above the town — The Railways Workers at Balaclava.. Click on thumbnail for larger image.

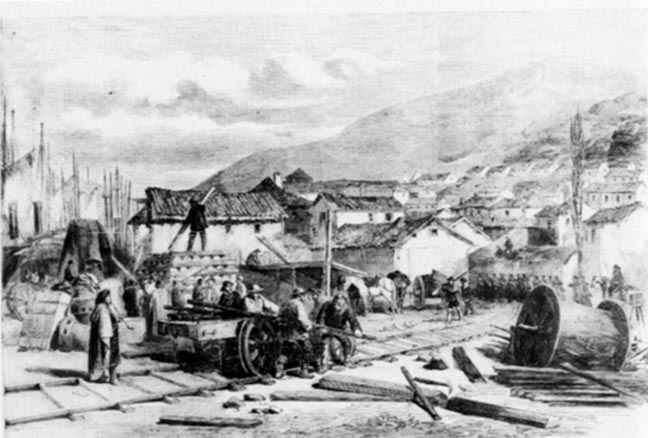

Their first job was to make themselves a home and set up a base. For the base they built a new wharf and tore down houses near the old landing place to clear a space for railway lines and sleepers. At the same time, on dry gravelly ground above the town, they erected their own huts, painting names on their sides — Peto Terrace, Victoria, Blackwall, London. Until then, they lived in their ships where every night Fayers preached to them as they darned socks and stitched clothes in the darkened holds.

They landed the engines and tested them, shrieking steam, in the high street. They turned the old Post Office garden — once a bright whitewashed place with grape vines trailing to the sea- into a plank and barrow dump. Within a few days the weather changed to a false Spring which deceived even native-born birds into nesting and trees into budding prematurely. Sickness incubated in the sudden warmth. Navvy demolition crews battered down the frail houses by the Post Office, tipping the rubbish over the putrefying bodies of the dead. Well-water filtered through corpses rotting and corrupting in the hills.

Recruiting the Navvies — "Mssrs. Peto, Brassey, and Betts, Waterloo-Road.".

In Balaclava, William Russell, The Times' war correspondent, had a house with a walled courtyard filled with Tartar camel-drivers and poplars. One day he left home as usual and, as was not usual, came back a week later to find navvies had bulldozed his wall and laid the railway through his yard. [145/146] Soon they were platelaying out of town (the Royal Navy and the Dorset Regiment had already scraped a rudimentary track to Kadikoi), switching from fearnought slops and thigh boots to flannel shirts and leggings to match the changing weather. (Everybody had a complete wardrobe — from painted suits and cotton shirts to lindsey drawers and mittens. All wore moleskin trousers.) Gales blew, the sun shone, it rained, it sleeted, it snowed, all within minutes of each other. Squalls ripped down tents and sent lumber cartwheeling away. Heat solidified the semi-fluid sludge underfoot, rain re-drenched it.

Railway Leaving the Harbour — Commencement of the Railway Works at Balaclava. Click on thumbnails for larger images.

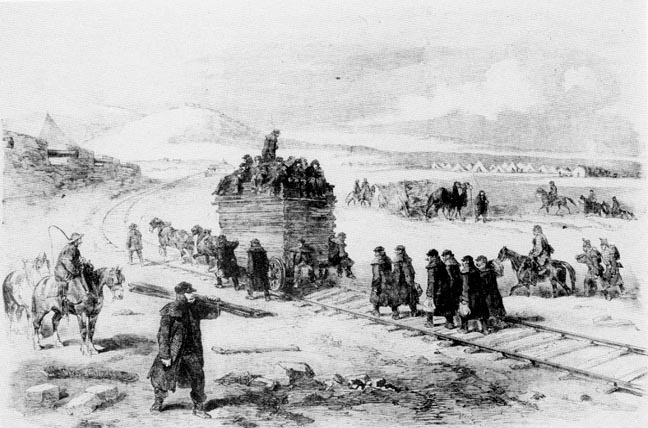

By mid-Febuary the tracks reached Kadikoi, curving away between the church and the guns. It was a strangely noisy war: gunfire and music, camels crying, people calling in a dozen languages, Eastern and European, then came the unaccustomed rumble of the railway, astonishing the Cossacks beyond the River Tchernaya, rearing their horses and waving their lances at the sight of the lines of little black wagons racketing along on the downslope When they could, they worked double-shifted, day and night. The night shift lay ballast, the day shift lay rails. Refinements like cuttings, embankments, and tunnels were impossible and the line wavered over the landscape. Once, when they had to bridge a stream, a pile-driver was brought up in the night, assembled in the dawn, dismantled at dusk.

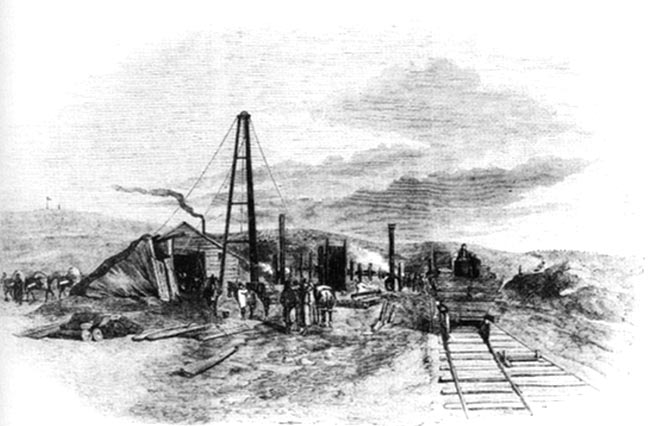

The Stationary Engine which Pulled Trains up the Slope by Kadikoi — Railway at Balaclava beyond the Camp of General Verey

Kadikoi.

Click on thumbnails for larger images.

The weather changed to and fro between winter and summer, thawing and deep freezing all the buried animal matter. Vultures, flapping blackly, heavy with human meat, worked a kind of shift system: half a week with the Allied dead, half a week with the Russian. Early March, and it froze again, chilling the shell-cases already being hauled along the railway to a munitions dump near Kadikoi. By mid-March the line topped the col on to the plateau: the stationary steam engines were in place, along with the tripod and the great drum which carried the wires for hauling trains up the slope. On the plain, ponderous dray-horses pulled the wagons between the harbour and the place where they were hitched to the steam engine wires.

Some navvies were already in trouble. One stole a pet bullock belonging to a French General. Another was flogged by the Provost Marshal to the amusement of his mates. He roared like a bull but remarked he had been flogged for the honour of his country. [146/147] Nevertheless they worked well in spite of the booths of Vanity Fair and Buffalo Town, civilian camps brimming with whores and amblers and drink-shops. Their popularity however was soon to collapse.

By Good Friday the railway was streaming with munitions and war material and that evening a train carrying the Highland Light Infantry jumped the track and killed a soldier. The Rev Fayers was there in the huts on Frenchman's Hill. The regiment, he said, was coming down in the dusk when dew had already oiled the rails. The track steepened around the side of Frenchman's Hill and the brakes couldn't hold the wagons whose rattle roused the navvies. 'Turn the points', shouted one. A man near a turn-out threw the switch and sent the wagons off the rails.

By mid-April the railway was carrying more ammunition than the bearers could handle. 'It is impossible,' General Burgoyne told Peto, 'to over-rate the services rendered by the railway, or its effects in shortening the siege.' That Spring they built lime kilns, stores, wash houses, and an Admiralty pier. Their well-sinkers sank the Navy a well, as their popularity slowly sank, too. Raglan wrote to the Prime Minister promising to shoot them if they grew more mutinous.

Then one evening in June a thunder storm turned the sky to fire and water and cut the peninsula in two like a brightly lit waterfall. On one side of a straight line water cascaded from the sky: on the other it was dust dry. Rain drowned men in the ravines, washed animals and huts out to sea, washed open the burying grounds of Balaclava, washed the corpses bare, washed bodies from their graves, washing them into a jumbled heap of bones. Rain broke the railway in places. Beatty was away, surveying the coalfields of Heraclea, and the navvies were uncooperative. 'The only obstructions to be dreaded,' Russell wrote in The Times, 'will arise from the "navvies", some of whom have been behaving very badly lately. They nearly all "struck work" a short time back, on the plea that they were not properly rationed or paid, or that, in other words, they are starved and cheated; the Provost-Marshal brought some of them to a sense of their situation, and, indeed, the office of that active and worthy person and his myrmidon sergeants has been by no means a sinecure between "navvies", Greeks, and scoundrels of all sorts.'

Duty or the cat-o'-nine-tails got them back to work, but in Russell's mind 'navvies' — now insulted with inverted commas — [147/148] were forever lumped with Greeks and other scoundrels. By late August they had all gone home. 'The railway corps is gone,' he wrote, 'and out of that stout body of navvies who were ready, while in England, to smash Russians with their pickaxes, but who became most peaceably inclined directly they saw the enemy's works, there now remains only Mr Beatty.'

Navvies at the Crystal Palace, Sydenham, 1853 — before the Crimean War. Click on thumbnail for larger image.

But a whole new navvy army was already mustered and on its way to the Crimea. The whole idea of navvy non-combatants may well have been Sir Joseph Paxton's — architect of the Crystal Palace — who first mentioned it in an election speech in Coventry in May 1854. In April 1855, Lord Panmure, Secretary of State for War, invited him to recruit a new Corps of Navigators to replace the men coming home from the Crimea. Paxton mustered his new unit — the Army Works Corps — at the Crystal Palace. It was semi-military and more regularly organised: men signed on for two or three years. They were unarmed, un-uniformed, not part of the regular army, but they thought they were bound by the Articles of War and the Mutiny Act. They were mobilised into twenty-five-man gangs commanded by both gangers and uniformed officers. The pay was thirty-five shillings a week for navvies, forty for gangers, and everybody was to get a twelve pound bonus at the end.

At first the Army Works Corps was to be a thousand strong but in September 1855, another thousand were recruited and in Octoberober Paxton asked Panmure for more. They were behaving too badly in the field for that, Panmure told him, though he did authorise a Commissariat Branch which reached the Crimea in January 1856. At its strongest the Army Works Corps seems to have had 2827 men and 77 officers. Superintendent-General William Thomas Doyne, a railway engineer, was their field commander. Robert Stephenson gave him a reference. Doyne, a gentleman by birth and education, would be able to deal with the officers of the Royal Engineers as an equal it was thought, though it turned out that Beatty was his main problem.

The Army Works Corps as a body had more trades than the Civil Engineering Corps. It recruited both navvies and general labourers as well as carpenters, smiths, hammermen, plasterers, glaziers, drivers, fitters, storemen, clerks, masons, quarrymen, sawyers, servants, brick- layers, wheelwrights, shoemakers, tentmakers, corporals and sergeants of police, plumbers. In Balaclava harbour a floating workshop, Chasseur, housed bellmenders, coppersmiths and [148/150] moulders.

Katie Marsh cared for them at the Crystal Palace, and saved their allowances in a Friendly Club until the war's end. She gave stamped receipts for their money-orders which once, in a nice gesture of trust, they flung back on the floor of her carriage. She lent them money to pay their drunk and riotous fines. She wrote to them in the Crimea. Mainly they were Lancashire, Durham and Northumberland men. Some were from Kent and Cornwall. Some were Scots, fewer were Irish.

By late June 1855, the First Division had embarked in the London River where the sailing ships Langdale and Simoon lay off Greenhithe. Barrackpore swung to the tide in Blackwall Reach. (When the Marsh sisters visited her, the men manned the rigging sailor-fashion and cheered.) In the Arcade Bazaar at London Bridge [ photograph] the Marshes bought chess sets, draughts, backgammon boards, games of 'railways and coaches', Chinese puzzles and scripture puzzle books to keep them from gambling on board.

With the next intake was No 551 Robert Bagshaw, 17th Gang, 1st Division, Army Works Corps, a lad from Grindlow, a lonely hamlet all alone on a great Derbyshire hillside, backed by a wooded ridge but fronted by a sweeping hollow scored by a labyrinth of stone walls like the foundations of an unbuilt Roman town. It's a little place of stone cottages and walled gardens with a rainy sky and a dry limestone ground. The world outside astonished Robert Bagshaw. On 21 June, a couple of days before the thunder storm in the Crimea, he wrote home from his lodgings in the Rambler's Rest, Hamlet Road, a street of cottages and stucco villas by the Crystal Palace. He was worried his parents would throw away the letter: it was his authority to the receiving officer to pay them twenty shillings a week while he was away, and alive.

He wrote again, 4 July. 'I now write to let you know that we are got on the vessel on Monday and we live like fighting cocks. At present we are very comfortable and quite hearty. I should like to hear from you but I don't know when we shall set out for our journey. We are going in a sailing vessel and they tell us that it will take us six weeks to go if the weather be favourable. There is two hundred going in the same vessel and we have got tools to take with us of all sorts. And I must assure you that if we had many a poor family we could fill them their baskets with meat we leave, and I hope if ever I return again I shall be able to let you have an account. [149/150] If ever you come to London you just take a trip to Greenhithe, where we are lying. It is the finest prospect you or I ever saw. You must give my love to my sisters Sarah, Mary, Judy and all inquiring friends. Tell them that I don't repent my journey as far as I have tried. You oblige me with all the news you can when you write to me, and I will send you all the news I can.' He added; 'The vessel we are going in is called Longdale. You must tell the Dusty Pits workmen that I enjoy very good health and plenty of beef and beer three times every day.'

He wrote next from Balaclava, 20 August. He had sailed on 6 }July aboard Barrackpore, not Langdale. 'We have a pleasant voyage thank God for it. We have had plenty to eat of the very best that could be had. I was sick only two days, passing through the Bay of Biscay.' It was a six week passage, as he had thought, and they had called at Constantinople, at which he marvelled. Greenhithe was quite forgot. He still didn't know where he was going and he still worried they were not getting his allowance. 'Be sure to put three stamps on your letters and address them correctly,' he said. 'Write back soon as possible.'

Russell, like a bearded barrel, still trod the Crimean circuit drinking other men's brandy. On 13 Augustust he reported that 'Superintendent-in-Chief Doyne had landed in Balaclava from the Orinoco after trans-shipping from Simoon in Constantinople. The railway staff were so reduced by sickness they were to be disbanded and Mr Beatty and some of his original gangers were to run it. Beatty, as well, was to build more lines to the Sardinian Army camp. Doyne's new navvies were to ballast and re-make the railway and build an all-weather road.

Lord Raglan had died late in June of diarrhoea and cholera aggravated, it was said, by stress. General Sir James Simpson, a long-headed Scot, a veteran of the Peninsula and Sind, now had the Army. The British had gone on strengthening their artillery opposite the Redan while the French sapped towards the Malakov Tower, the real key to the taking of Sebastopol.

The flowers were withered in the sun-browned landscape lined by grey mountains. Close up, the Crimea was black with flies, clustering on every forkful of food, drowning in every cup, sleeping in solid black colonies on ceilings where the merest glimmer or candlelight woke them, buzzing with high-pitched irritation.

A week before the Army Works Corps arrived the French and Sardinians fought and won a pitched battle on the River Tchernaya, north of [150/151] the rivers gorges. The dead of three massed Russian divisions, blown apart by gunfire, lay so thick by the river the Allied cavalry wouldn't let their horses drink there. Russell wrote of a three-day cannonnnade of Sebastopol which had just ended, burning fuses arching through the sky like tracer bullets in later wars. Ice came for the hospitals and Simoon and Barrackpore berthed, full of Army Works Corps men, Robert Bagshaw among them.

By mid-September, Russell reported, sixteen per cent of them were dead. He blamed drink and the things they ate. Mrs Seacole, late of Jamaica, doctored them in her restaurant, a ramshackle of iron stores and sheds close to the railway on the rising ground between Kadikoi and the col. Mrs Seacole, a kindly body (a sort of lesser Florence Nightingale), also tended the wounded in the trenches.

What was more important, was Doyne's immediate problem, the railway or the all-weather road? Beatty and the railway were independent of him and Beatty had the Generals on his side. He controlled the tool-making ship Chasseur and was able to raid Doyne's Army Works Corps for labour at will. The Land Transport Corps which ran the railway asked for and got Army Works Corps brakesmen and pointsmen as well as carpenters to make and fettle wagons and build and run a sawmill at Sinope. It didn't take Doyne long to decide a road was more important, and that his whole command would be ruined if he couldn't control Beatty. Give Beatty the means to tinker with the railway on his own, Doyne told Paxton, or give Beatty and the railway to me. In the meantime he began work on the Grand Central Road, with five thousand soldiers and all the navvies he could wrest from Beatty, two hundred of them. Within a few days exasperation got the better of him and he wrote again to Paxton. 'I am doing everything in my power to make this disjoined system work,' he said, 'but I regret I do not receive from Mr Beatty that disinterested co-operation which I have a right to expect. The utmost I have succeeded in doing is to avoid an open quarrel, which the tone he adopts is calculated to produce.'

Sebastopol had already fallen. 'I saw it all on fire one hour after it was taken,' said Robert Bagshaw, inaccurately, 'and got a gun and a sword from the Russians. We was about four miles from the town when it was taken and the shot and shell shook us in bed for three days before.' The last barrage began around dawn, Wednesday 5 September: a [151/152] still morning with light airs from the south-east, too light to ruffle the sea where ships sat reflected upside down, full length, in its sheen. Sebastopol is split in two, east and west, by the harbour into which the River Tchernaya flows. The southern half of the town is similarly split, north and south, by the Dockyard Creek which then ended almost at the British lines and pushed on through them as a ravine. A floating bridge of boats linked north and south Sebastopol, while the harbour itself was closed by a chain of ships: steamers, frigates, old two-deckers.

The final battle began with the firing of buried mines, gushers of flame and earth, reddened by the morning sun. Three miles of artillery fired simultaneously, the heaviest, loudest, most compact massed gunfire of its time. They fired almost without slackening until the last infantry charge at noon on Saturday.

Once taken, Sebastopol became a tourist trap for off-duty troops and navvies. The Russians now shelled the city from their positions in the north. One Sunday in Octoberober a shell burst near the Imperial Barracks. An Army Works Corps man strolled over to examine the crater, clay-pipe in mouth. After appraising the shell-hole, pipe still sparking tobacco, he strolled off to examine the barracks. The Russians had been messy, and loose powder littered the floor. A tobacco ember snorted from the pipe, lit a trail of gunpowder, phutting and cracking like a firework. It reached the magazine where roof, walls, flame, smoke all blew out together. Nobody said the navvy died.

Work on the central highway began soon after. 'Many a time I have wished myself at home,' Robert Bagshaw wrote to Grindlow. 'But I am settled at present. We have done very little work till this last week and we are making a road from Balaclava to Sebastopol, and our officers tell us that we shall be able to have our dinner at home on Christmas day.' At first it was proposed to repair the old roads between Kadikoi and the crest of the col and introduce a one-way system — up the old French route in Vinoy Ravine, down the old cart track around Frenchman's Hill. But Doyne thought a new road was needed and, since Beatty had surveyed the railway so well, it was to parallel its tracks most of the way.

A ditch was dug to drain the Balaclava plain. Drains, cross- connected by ditches, were dug in the flat boggy parts near the harbour and the road was macadamised with stone pitching. For a time all the Army's traffic was driven over it, like a non-stop roller, [152/153] and in the mornings and evenings navvies consolidated it even more.

On the rising ground, the road wound around Frenchman's Hill, terraced into the hillside. From Mrs Seacole's place the old road was widened, drained, raised and metalled. Above her the road was again terraced into the hillside. Wet places were drained by a zig-zag of ditches converging on old water barrels and pork casks From the top of the col the highway crossed the plateau and the Woronzov Road into the Light Division camp. A wide strip of top soil, a shallow clay, was scraped away to bed-rock, a kind of oolitic limestone. In places the limestone was left to weather and harden. Elsewhere limestone chippings were carted in. For the winter they planned to hang lanterns from the mileposts to pick out the road through the snow. At the same time, the railway, which had been hurriedly laid on scraped earth, was properly bedded, drained, ballasted, and doubled into a two-way track. By the end of November two steam locos. Alliance and Victory, worked the low ground below Kadikoi, supplementing the ponderous horses.

The rest of the Second Division came in Octoberober 1855, some landing from the Telegraph and (those who hadn't jumped ship in Malta) the ss Azoff. The Third Division was recruited in November. They had their own chaplain, a muscular Christian called Hudson who had already scaled Mont Blanc by the straightest route. Work was scarce in England and 'mechanicals' from the manufacturing towns now volunteered, reaching the Crystal Palace without money and, until they signed on, without wages. Katie Marsh bought them hot penny pies every day from a London pieman and coffee and bread from a nearby coffee shop. Because they needed references she turned her father's Beckenham rectory into an unofficial Army Works Corps office from where they could write to their old masters. Jura sailed in Decemberember, the last of the navvy ships.

In February 1856, a detachment of the Army Works Corps came under fire as they took up new quarters in the dockyard where they'd been sent to mend the Woronzov Road between Cathcart's Hill and the Creek Battery. Gunfire had smashed the drains, embedding half a dozen gun carriages in the mud. Russian artillery shelled them as they re-made the road alongside the creek in the harbour. Later they helped the submarine officer dive for brass field guns. [155/156]

March 1856, was cold and frosty and it snowed. Commissariat Department navvies began building a dam to pipe water to the Castle Pier. Bricklayers and navvies struck work and had a week's pay stopped to induce them to behave. A hut burned down, killing several men. On the 19th, a bright Sunday after a boisterous Saturday, Ganger Marks was reduced to the rank of navvy in his own gang. Cooper's Foreman McPherson was reduced to his trade. Next day fog rolled in from the Black Sea and Marks was made up to ganger again, at a reduced wage, and McPherson was sent to headquarters as a horse thief. On the 28th the water was turned on for Castle Pier.

Disciplined Army and undisciplined Army Works Corps now clashed more often. 'The Army Works Corps,' complained General Simpson, 'are by far the worst lot of men yet sent here. It is ruin to our soldiers to be placed in contract with such a set of people, receiving higher pay than themselves.'

Doyne's troubles with Beatty seem to have ended in November 1855, when he and his staff were transferred to the Army Works Corps. But Doyne still had trouble with the Army and his own men. Army Works Corps officers looked martial — like sharpshooters, said Russell — in their grey, blackbraided uniforms, swaggering about with swords and telescopes, but they seemed unable to keep order. According to Katie Marsh navvies refused to touch their caps or pull their forelocks to any officer and were flogged for it. 'We've come to work,' they said, 'and can't awhile do manners.' According to Doyne, he scarcely had any authority over his men at all. Those Articles of Agreement everybody signed at the Crystal Palace had no meaning at all in military law. At home, the Judge Advocate General ruled that the Army Works Corps was not subject to the Articles of War or the Mutiny Act. To the Army they were camp followers, bound by a civil contract — not with the Army — but with Doyne personally. The Army consequently refused to flog or discipline them and all Doyne could do was stop paying and feeding them when they broke their side of the bargain. A letter from Panmure gave him authority to fine them though Doyne doubted its legality.

In April 1856, General Codrington, who had taken over from Simpson, learned the Army Works Corps were misbehaving: a hundred men had been idling on the wharf instead of unloading wagons and a homeward bound division were disgracefully drunk on board Cleopatra before she put to sea. If they didn't change their ways, he [154/155] threatened, he would have their gratuities stopped. Doyne, upset by the ingratitude as much as anything else, wrote to Paxton from Bleak House, the Corps' Crimean HQ. He listed everything the Corps had done: ballasting, draining and reconstructing the now nineteen miles of railway; building extra track to the Sardinian Army lines; helping to run the railway with drivers, brakesmen, pointsmen; making and mending wagons for the railway; building and working a sawmill at Sinope for the Land Transport Corps; building quays in Balaclava harbour and piers elsewhere; working as stevedores and dockers: building the 11th Hussars a stable; building hospitals; sinking wells and building dams. Above all, making the Central Road, and making it as good as any turnpike in England. The Corps would have done more, he went on, except the Army hindered him. The Army was ninety per cent inefficient and always over-manned — the reason for the men idling on the wharf. On top of that he had a lot of lazy and mischievous fellows whom the Army refused to flog. When less labour was needed he shipped the worst of them home in Cleopatra — the drunks who upset the General.

Cleopatra got home to Portsmouth in May 1856. Navvies still in the Crimea were tearing up the tracks which the Government sold to Turkey. Two days after Cleopatra berthed, the Clyde sailed from Balaclava. Behind them they left the road and a stone tablet set in a rock near Kadikoi: 'This road was made by the British Army, assisted by the Army Works Corps, under the direction of Mr Doyne, CE, 1855.' Near the road they left their graveyard.

Those who came home, came home to a lot of money. In Beckenham they reported in their hundreds to Katie Marsh to collect their savings. Sober, they had to be, and carrying their Army Works Corps engagement papers. One West countryman immediately bought a gold watch chain, silver watch, blue pilot jacket, plaid trousers, green velvet waistcoat and blue glengarry. Another (a bricklayer) bought enough bricks, slates and timber to build himself a cottage. More typically Northumberland John blew two hundred pounds of accumulated pay in a single binge in Barnsley.

Robert Bagshaw was still alive, still on the First Division's payroll, still with the 17th Gang, still paying his parents his pound a week allowance, in May 1856. Perhaps he got home.

In 1858 Thomas Fayers met one of his Crimea navvies again one bright Sunday morning in Januaryuary by the Westmorland Lune. Curly Joe was lacing his boots in his hut, his back to the open door, [155/156] when Fayers called. 'If that ain't our Crimea parson, I'm blowed,' said Curly. He followed Fayers to the meeting ground, boots untied, amazed to see his Crimea parson again. After that Curly often went to his meetings until he was put off by his mates' raffling him.

Forty years later Crankey Oxford, an old Crimea navvy, died at the Barnes reservoir in London.

In 1903 Robert Muras Spowant wrote to the Adjutant-General's office from New Zealand:

Sir, After such a long lapse of time you may not be able to supply me with a proof of my being one of the Army Working Corps under Sir Joseph Paxton that the Army would be more available for the Field in the Crimean War by this AWC relieving soldiers from the necessary work required. I joined and was sworn in among many at Sydenham Crystal Palace then not in a finished state in 1854 about 500 of us left the Thames London on the Hansen, a German paddle Steamer and was landed at Balaclava Crimea.

After Peace was proclaimed some 300 of us returned to London on the screw boat named Antelope (the corps I heard numbered 5000). I would be thankful for a Form of Proof of the above if there is a record of my name in said corps — as I am now 78 years of age, born in Spittal, Berwick-on-Tweed, April 1825. They are having a Veteran Home in Auckland, NZ, and the proof I ask may secure me this claim.

He added: 'I may mention that I was a carpenter and worked on the railway works, our camp of V Huts were near on the opposite side of the road; we were a little above the land locked natural harbour of Balaclava on the Black Sea'.

It wasn't long before the Royal Engineers taught themselves to build railways, proficiently, laying up to two-miles of track a day across battlefields, yet oddly enough when the Army needed a line between the Red Sea and the Nile in the> Gordon campaign the War Office put the contract out to civilian tender. Lucas and Aird won it, shipping all their material — from locos to electricity generators — from London and Hull, each ship carrying everything needed to lay five miles of track.

They began on Quarantine Island in Suakim harbour in March 1885, but got no farther than Otao, nineteen miles away, even though it was an easy job: easy engineering, easy gradient, easy [156/157] terrain. Instead of the Army's pacey two miles, less than a mile a day was ever laid. The Royal Engineers blamed the civilians. Lucas and Aird were too inexperienced in military affairs. They should have built a dock. They should have built a materials' park. They should have run trains to a strict timetable and used the telegraph and line-clear system. They should have used bigger engines to save wasting time getting up steam at every minuscule hill with their piffling little locos. They should have used the metre gauge: it was lighter, needed less ground clearance, and its engines and rolling stock took sharp curves more easily. Above all they should not have used expensive fifteen shilling a day civilians when they could have got local labour for twelve pence.

The line was surveyed by the Royal Engineers. The ground was cleared by Indian civilians and the Madras Sappers. Indians unloaded and loaded the trains. Carts, mules, muleteers, horses and horse drivers were all Government supplied. Rails dropped off at the railhead were dragged into place by horses of the Indian Supply and Transport Corps. Sleepers were carted by Maltese muleteers and laid in place by local labour. All the navvies did was drive the trains, position the rails and spike them.

The navvy force was called the Corps of Volunteer Engineers. Five hundred of them went, beginning in February 1885, when over a hundred sailed in the Osprey, all fairly well boozed after a day's wait in the Emigrants' Home in Tilbury. Lucas and Aird sent a telegram wishing God's speed. In the Sudan they strutted about bowler-hatted, flannel-shirted, beer-swilling, in the heavy sweltering heat that was like a material weight. At noon the rails were untouchably hot. Temperatures were a hundred degrees Fahrenheit and more in the shade of their sideless mess tents.

John Ward was there. In the 1890s he claimed he had led a strike against pay and conditions in the Sudan. It's doubtful that he did. The men were too preoccupied with dying. They died of heat stroke, like Devon Billy Fennymoor; they died of fever, like Lincoln Joe Godfrey. By the late summer they were straggling back home to die in Devonport Military Hospital, like Missionary Moorley who was landed there sick from the Tiverton.

Lucas and Aird fared better than their men — they probably made a profit — but it should be said failure like this, by contractors as big as these, was always rare. Big contractors were successes. [157/158]

Last modified 19 April 2006