Things often went awry on public works, though alcohol was a commoner way of forgetting it all than nicotine. Most sensitive people were terror-trodden, down-trodden with fear, and what the sensitive felt acutely, the insensitive sensed more dully. Pain was public and commonplace on public works, pain-ridden, death-ridden terror-ridden places.

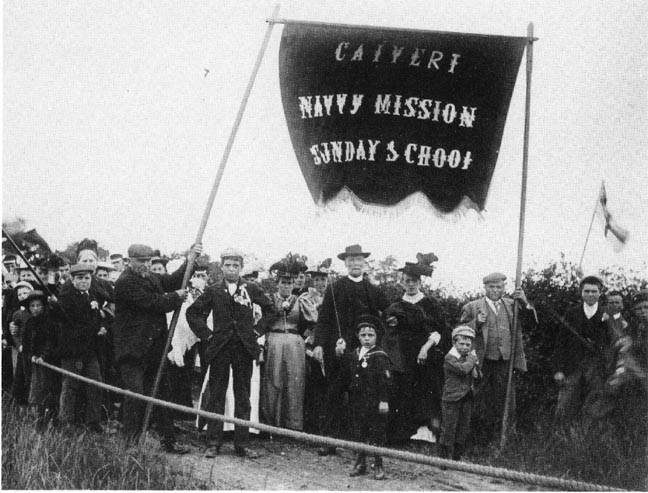

Calvert Navvy Mission Sunday School. Click on thumbnail for larger image.

Even the religion instilled by the Mission was doom-ridden — for all its cheerfulness about salvation — and what people remembered most was the threat of hell where somehow the body fats fried on your bones eternally and the malice and spite of the world were moulded together, magnified, and given black-hot flesh as the Devil, an ugly implacable thing with skin so smouldering it would burn the hand of any mortal man who touched it.

The Victorians, any way, seem death-haunted. In old photographs you can see death in many a sunken face — whole families, even the smallest children still in pinnies, identically marked with death, illness or insanity. It was a necro-conscious society.

In navvy huts the dying and the newly born almost shared beds, passing each other in and out of a defiled world. A child growing up on public works was circumscribed by pain and the realisation that suffering had no natural end: it went beyond what the human body could humanly be expected to endure.

To begin with, there were accidents. In 1906, when navvy work was scarce, Patrick MacGill climbed on to a railway embankment near Glasgow straight into a dead man's job. They were carrying away what was left of him, bits of him in a bag. A rail had slipped from a wagon. 'It broke his back,' said a navvy. 'Snapped it like a dry stick.' They heard his spine snap and saw him fall under the loco. A thin slice of flesh, perhaps his tongue, lay near his disconnected fingers. An old man picked them up, grotesquely counting them into a bag. Men fingered bits of the dead man's meat [33/34] sticking to the loco.

Statistically he was one of four to die on public works that day. Another eight would have been severely hurt. There was, said Mrs Garnett, a death for every mile of finished track, one to thirty deaths a tunnel.

There's little doubt that navvying was the most dangerous job of its day: worse than coal-mining, worse — according to some — than war. More men as a percentage were killed in the Summit tunnel than in the battles of Salamanca and Waterloo. A navvy stood the same chance of being killed as an infantryman in the> Boer War. By then actuarists worked on the assumption that every million pounds' worth of contract would kill a hundred men.

A tenth were killed by things falling on them, or by falling of things — into> puddle trenches, down shafts, into cuttings. A man killed his brother at the Sapperton tunnel in 1787 when he dropped the muck he was winding out of the shaft. Men were hurt at the Strood tunnel, 1819, when some vandal half-cut the winding ropes.

At Eston, a navvy told Mrs Garnett, there was a place they called the Slaughter House because of the daily accidents and weekly deaths [It isn't clear where this is/was. Eston, south of the Tees at Middlesbrough, has no deep cuttings.] 'There were the chaps,' said the navvy, 'ever so far below and the cutting so narrow. And a lot of stone fell, and it was always a-falling, they were bound to be hurt. There was no room to get away, nor mostly no warning. One chap I saw killed while I was there, anyhow he died as soon as they got him home. So I said:

"Good money's all right, but I'd sooner keep my head on", so I never asked to be put on, but came away again.'

Falling machinery killed Hope and Anchor at Boston dock, 1884. Falling muck crushed Soldier Cobb's legs at Hackney sewage works and held him half-upright in dirty water all day and night. Cumberland Tom, a sun-tanned old soldier, fell into the Fontburn gutter with his horse, 1904. Bingy Daft broke his thigh when a gust of wind blew him off the Howden dam, Birchinlee, 1910.

At Chichester we was laying a pipe track opposite the barrack gates and I got buried there. All of a sudden the blooming side come away. The daft fools started digging down on me. Then two navvies come along and dug down the side of me and got me cleared. When they got me out on top I couldn't feel a thing. I was numb. All numb. I [34/35] was taken to the workhouse infirmary in a horse cab. I was there two near three weeks and come out and walked all day and all night and all next day and went to my brother's. Then we stood up in a pub all night pouring beer down our necks.

Machinery killed another tenth. Johnny Good Morning's foot was crushed by a wagon at the Oswestry dam, 1888. A dobbin can ran over Hash Harry on the Southend-Maldon, 1889. A stone-crusher broke Egypt Slen's back on the Ship Canal, 1890. A loaded cart ran over Crying Nobby at Great Missenden, 1891, the year Hair-oil Pindar was run over and killed at Bob's Bridge, Ship Canal, and Mexican Joe lost his big toe to a runaway wagon at Chesterfield. Navvy Parson's eye was plucked out like a bird's egg on the Princes Risborough railway, 1903.

Four per cent drowned. Bristol Nobby did when his boat turned turtle in the Tavy, 1889. Up-the-Tree Nobby drowned in the Kent at Kendal, 1892. Ann Lovesey drowned in a well at Moreton Pinkney, Great Central Railway, 1896. Bisbrooke Billy drowned in sewage in Manchester, 1893.

We got along one day from No. 1 shaft in the Llangyfellach tunnel when we got into bad ground. There was peat on top, then gravel, then four feet of coal, then rock, and then the water began to pour down. The water did pour down, right enough. There was a bog on top and the tunnel was draining the water off.

Then, one night, the bog broke through. It'd been weeping all the time, then it come in with a rush. We'd been working in oil-skins all along. It did come in quick. It was half full of water in no time.

The> banksman lowered the cage down and took up the ponies first: next to them came us navvies and then the> tigers. The water was up to your chest and still rising. We got on to the tubs and stood up. The candles went out. It seemed a long while, but it wasn't long. It wasn't warm, it wasn't hot, but it wasn't anything to complain about.

[The Llangyfellach tunnel pierces the massif between the River Tawe and the Afon Llan. Swansea, like a threat, looms over the hill to the south. The ventilation chimney over No. 1 shaft is still there, in a soggy hollow on the edge of a golf course.]

Another measurable percentage were burned, scalded, or exploded — generally to death. Devon's arm was blown off and his eyes blown [35/36] out at Barry dock, 1885, the year Cyder Tommy was blown apart, charging holes. A year or so later, Bristol took a lit candle to a powder box and lived a few days longer.

I went back to Lunedale, driving a tunnel from there to Baldersdale. The tunnel was eighteen inches out of centre and we worked there blowing the side off, on nights. Hammer and drill work — the drills were thin things like pokers, about three feet long. Micky Mitchell had charged the holes and they hadn't gone off. I went back down the tunnel and I could see the last hole burning. I turned in a hurry, knocked my lamp against the side. Lamp went out and I lay against a tub. About thirty charges went off. The place was full of smoke - all dust and muck. I left there soon after.

Drink, directly or not, was a common cause of death. A train cut off Putsey Bill's arm as he lay draped, drunk, across the railroad track at Cullingworth, 1883. Next year Black Joe's George was drowned, drunk, in a brook and Jimmy Drew was stung to death by an adder one lazy, insect-humming day as he lay, drunk, on Effingham Common. Lady Killing Punch, while drunk, bit a ganger's finger in Bolton. The wound festered and the ganger died, 1891. Rats ate Yorky Fenwick's corpse at Millom breakwater, 1902, where he drowned himself while drunk. 'Such is the end of the ungodly,' said Mrs Garnett.

Then there were the other ways of dying, each too few to make statistic. Bible John gored to death by a milk cow at Leeds sewage works, 1884. John Mornington, a CEU man, killed by a Birkenhead taxi-cab. 'All is well with my soul,' were his last words. Swillicking Dick, frozen to death, alone on the moors above Accrington where the mill chimneys stuck up like black-hot pokers. Bullock's Liver Punch hanged himself at the Moorock, a pub near the Catdeugh dam, 1894. Januarye William died 'for fear of thunder', 1895. Owd Lijah fell into an old quarry on an outing from the Saddleworth Workhouse, 1900.

A big sea, breaking over the half-finished Admiralty Pier, Dover, washed away the blacksmith's shop and a group of navvies, 1903. Pyfinch was impaled on a stake, 1904. Soldier Tom was stabbed to death trying to stop a knife-fight between a man and a woman on the Castle Cary-Langport line, 190$. Grimsby Jack overdosed with laudanum at Birchinlee, 1911.

But bad as it was, death by accident was less significant, [36/37] statistically, than death by disease: forty per cent, against sixty.

Pneumonia, in fact, was the biggest single navvy-killer of them all, killing a tenth of everybody on public works on its own. Pneumonia, added to other illness of the lungs and breathing - tuberculosis, bronchitis (brownchitis, to the navvy), congestion of the lungs, inflammation of the lungs — killed a fifth, twenty per cent.

Inflammation of the lungs killed Bridle-mouth Punch at the Ramsden dam, 1882. Bronchitis killed Crooked Arm Jack at the Sabden dam, 1888. Congestion of the lungs killed Hard Labour at the Cwm Taff dam, 1889. Bromichem Punch died of bronchitis and inflammation of the lungs at Newport dock, 1890. Pleurisy killed Virgin Slen, 1896. Pneumonia finished Unfinished Lank, 1900.

Heart diseases, kidney failure (often listed as Bright's disease), cancer, typhoid, bleeding, killed another tenth. Fighting Sammy died of a supposed heart attack on the Ship Canal, 1888. 'Overflow of blood at the heart and cancer of the stomach' killed William Fleming, 1897. Bumble-Bee Dick died of heart failure and pneumonia at the Totley tunnel, 1893, above the River Derwent in Derbyshire.

Billy the Finisher's wife died after a long sickness at the Sabden dam, in the witch country under Pendle Hill, 1888. Sunstroke killed Cheshire George, same year, same place. Hoping Dick broke an ankle that wouldn't set, on the Ship Canal, and died in agony, 1889. Peg Leg had an unhealing ulcer on his stump, Ship Canal, 1890. Old Black Tommy, alias Linky Loo, died of old age in Keighley Workhouse, 1896. Dog Belly was killed by a stroke, 1900, on the Chipstead Valley line.

Even epidemics were statistically significant. On the London-Birmingham, men walked about speckled with small-pox pustules, while cholera killed nearly thirty people at the second Woodhead tunnel, 1849. In the early '90S, scarlet fever, diphtheria, and small-pox outbreaks put part of the Dore and Chinley line into quarantine, particularly around the Totley tunnel where, in spite of the quick, pebble-rolling Derwent, drainage was bad and where, on top of everything else, they had a typhoid epidemic as well. Navvy Smith, missionary, coped with typhoid and whooping cough on the Great Central, 1896. 'The bell is tolling for six to be laid in their graves today,' he once noted.

Solitary graves opened and closed like mouths on public works, but so did the odd mass-grave following the odd mass-accident. In 1891 a nipper working a turn-out on the Ship Canal accidentally [37/38] sent a muck-train into a siding at Ince. The train hit the buffers and dropped over the edge of the cutting (past a navvy called Sloppy clinging to the canal wall) hissing, steaming, scalding, hot ash and coal spilling from its fire box. Ten were killed outright.

The Mission buried the Protestants in a common grave in the churchyard at Ince, a village on a mound in the marshes overlooking the green saltings and yellow sandbars of the Mersey all as flat as the river.

Sometimes well-meaning ladies opened hospitals — they did on the Newbury-Didcot in the 1880s — and so, sometimes, did contractors: Enoch Tempest had a hospital of sorts in Dawson City, the settlement servicing the three dams in line astern at Walshaw Dean in the tweed-coloured Pennines. But the only place on public works to run a proper accident service seems to have been the Ship Canal, where First Aid Stations the length of the cut fed casualties into base hospitals at Latchford, Ellesmere Port, and Barton: grim, two-floored places full of pain and starchy nurses in caps like cocks' combs. Casualties had priority on the overland railway and a telegram day or night brought the doctor from Liverpool, a Welshman called Robert Jones, the last of a line of journalists, surgeons, and bonesetters.

But, mostly, men depended on their Sick Clubs for support as well as the navvy custom which permitted an injured man to be kept by his gang until he was better. Often, another man from his gang was detailed to rough-nurse him among the restless bodies in the huts. (It wasn't until the 1880 Employers' Liability Act that anybody had any entitlement to insurance at all, and then only if the contractor was to blame for what happened. The 1897 Act was limited to employers rich enough to be able to pay.)

Illness and accident were not the only affliction to hit the young and able bodied. People starved when frost stopped work. Soup kitchens were not uncommon, particularly on remote dams in winters like that of 1895/6 when flour, potatoes, meat, and clothing were sent to the Yorkshire moors to the Gowthwaite and Dunford Bridge dams. A few years earlier, people were dying of hunger at Vyrnwy and, a year or so before that, bread, bacon, and coffee were doled out at the Bill o' Jacks dam near Greenfield in Lancashire. Soup doled out to navvies working in the Blackwall tunnel in London in 1894/5 was paid for partly by local donations, partly out of what was left of the Distress Fund which was set up when work on the Hull-Barnsley line and Alexandra Dock was stopped in 1884 [38/39] after the promoters ran out of cash.

Many navvies stayed on at Hull, expecting work to start again. Others sailed to Tilbury docks straight into another stoppage caused by an argument between companv and contractor over extra money for working the stiff blue clay of the lower Thames valley. In Hull, work didn't re-start, either. People went hungry. Boots and working clothes were pawned. Men lost weight and strength. As soon as she heard about it Mrs Garnett appealed for help in the newspapers, raising enough money to feed the people who stayed. Katherine Sleight and a committee of gangers spent it on bread and cheese bacon, meat-and-potato pies, soup-kitchen soup, and fares to other jobs. 'When we started these works,' Thomas Walker wrote from Preston docks, 'numbers of men (walking skeletons) came on at once from Hull. They were not fit for work, they were starved.'

All in all, Mrs Garnett thought the Distress Fund was such a good thing, she proposed extending it countrywide. On one summer's day every year all over England a silver collection would be held on every job. It was to be called the Distress and Self-Help Fund, and it came to nothing. Nobody even went to the meetings she organised. 'I did think,' said a sad and angry Mrs Garnett, 'that the real navvies would have taken this thing — which was for their own good only — up with some spirit. I am sorry that you have got so little pluck or sense. You may think I am speaking sharply, and so I want to do.'

Not long after, work stopped on the Christchurch-Brockenhurst and the Christchurch-Bournemouth railways. People were distressed. 'You know I begged you to provide against an evil day by giving to a Distress Fund,' she told them all, 'and you would not do it. Now I ask you navvies all over England, what do you think of your own actions?'

It made no difference. If anything things got worse. In 1907 men earned up to seven pounds a week laying a sewer across Blackheath in London. Within a fortnight they were begging. 'When I think what a class navvies were in the old days,' said Mrs Garnett, 'and then see dirty men in rags adorned with red noses, who say, "I've come for a little relief. I'm a navvy," I feel, and often say, "That is a lie." "Rags outside and rags in" is a just description, but not the noble old name navvy.'

Not that it was always the navvy's fault. There was a time, early this century, when to be young and fit in the summertime was no guarantee of eating. The only overtly political thing the Navvy [39/40] Mission ever did, in fact, was lobby John Burns, President of the Local Government Board, about navvy unemployment — in particular about Ramsay MacDonald's 1907 Unemployed Workmen's Bill which was never enacted but which would have given the unemployed the right to either a job, or board and lodging for life. It was meant to stiffen the 1905 Unemployed Workmen's Act which kept respectable people away from the Poor Laws by keeping a register of the genuinely unemployed and by giving Distress Committees power to spend ratepayers' money on relief schemes.

It was these relief schemes in particular that worried the Mission. They saw them as discriminating against the navvy, who was disenfranchised because he had no fixed home, in favour of natives who were both out of work and a burden on the rates. Some councils even put ads. in the newspapers warning navvies to keep away.

Burns gazed at them with intense, deep-set eyes: a slight, lean faced man with short pepper-and-salt whiskers and an untidy tie. A hundred years earlier the mere displeasure of a Bishop of London had stopped navvies working on Sundays: now Burns, the first working man to sit in the Cabinet, had another Bishop of London in the delegation in front of him. What you're saying, Burns summed up, is that the state's recognition of everybody's right to work was hurting the rights of navvies to do work that was theirs traditionally. 'Local work for local men means local jobbery and local extravagance,' he agreed. He agreed, too, that unagile and untrained men meant inefficiency — and what was the point of training natives for public works if they clung to their back streets and refused to tramp to distant parts?

But you are more frightened than hurt, Burns the politician reassured them. Many relief schemes were purpose-invented. Hackney marshes were being raised for no particular reason. What contractor was going to lose money hiring 'industrial inefficients' on real jobs that really mattered? Where there was genuine navvy work, genuine navvies would do it. Out-of-work tailors, watch- makers and tram conductors would never build dams. (Relief [40/41] schemes, on the other hand, delighted many a navvy. It was easy work — planting trees, laying drains, making roads; road-making was never navvy work, except in the> Crimea. Relief pay, though poor, was regular and the money never stopped when the weather stopped the work. Hours were short, the living easy.)

There was, however, a darkness about those years. Illness and old age were the things that worried navvies most: both took away the one thing you needed to make a living — strength. Dying young, in a way, solved the problem of living when you were old.

'And where are the old navvies?' Katie Marsh asked in the 1850s. 'Dead,' she answered. 'Every one.'

She had watched hard work visibly age young men. Old Edward on the Beckenham railway, a grey-haired elderly-looking man (pushing seventy you'd have said), was in fact only thirty-eight and obviously not going to get much older. Navvies worked too hard and lived too rough. Men ate their snap sitting in grass wet as a pond. There were no tommy sheds or shelters.

'Where have all the navvies gone?' asked young Lord Brassey, in the '70s. 'Emigrated, every one.'

Reality, however, was closer to Katie Marsh. Navvies either did die young, or died old in dolour in the> workhouse. 'I expect I shall die like a lot of the rest of us, in a hedge bottom,' an elderly navvy once told Mrs Garnett.

Come to that it was a recognised thing at one time for old navvies to end up in the workhouse. They used to call it the Spike in them days. Or the Grubber. Horrid places. (And some of them old kip houses were horrid places and all. They were alive. Not lice, hugs. Of course, it was a good thing to get you up in the mornings. Horrid places, even the fourpenny ones.)

Some few (some very few) of the soberest cutters stayed to work the canals. Thomas Telford recommended John Ford — 'an old canal man' — as a bank tenter (today's lengthsman) on the Liverpool-Birmingham, where Benjamin Moffat, gangman of horse-work on the great slipping bank at Shelmore, was also offered a permanent job.

Some maimed cutters with names like Hoppity Rabbit and Dai Half eked out a living carrying news from job to job, not only as "limping scandal sheets but by relaying what the wages were and [41/42] where the new work was.

Good railway contractors like Walker and Firbank retained men crippled in their service as watchmen. Until he died in 1886 it was said no old Firbank navvy need fear white hairs. Walker's 'Fragments' were famous on public works for their ferocious loyalty to him. Once a geologist carrying Walker's written permission tried to climb into the Eastham lock on the Ship Canal to look at the boulder clay. He was stopped by a Walker Fragment: a man, the canal's historian tells us, with one foot in the grave, the other made of wood. The geologist tried to out-run him. The Fragment whistled down the cutting. A one-armed, but two-legged, Fragment popped out. Between them the Fragments had three arms and three legs. The geologist-out-armed and out-legged — went home.

Walker also kept old but unfragmented Fragments, grouchy to everybody else but loyal to him. 'I'm not paid by my employer to make a collection for myself,' one old watchman on the Ship Canal would say, rejecting tips from the trippers. Sam Hall was no fragment either — he was whole in every limb -he was just old. Ninety-three, in 1889, when he became a watchman on the Ship Canal.

Some few (very, very few) saved up and got out, like one of two navvies engaged to sink a well at Craven in Cleveland in the 1860s. One opened a greengrocery near Chester with the money he saved, the other went his dissolute way. Later, they met in a Cheshire lane: the saver in his two-horse cart, the spendthrift on his two tramp feet. While the greengrocer prospered, the tramp navvy died of drink at the Lindley Wood dam, still carrying his family under his hat.

Mayhew, researching London Labour and the London Poor, met two navvies going different routes around 1850. 'Before I come to London I was nothink, sir,' said one, a tall man with sandy whiskers strapped under his chin. 'A labouring man, an eshkewator. I come to London the same as the rest, to do anything I could. I was at work at the eshkewations at King's Cross station.' He came from Iver in Buckinghamshire and had first gone navvying with his brothers who were hagmen with Peto. [Hag, hagman, hagmaster — a sub-contractor]. When Mayhew met him he was dressed as a costermonger, selling pickled eels in Chapel Street market. Rat-catching was his sideline (sometimes, for a bet, he bit [42/43] rats to death with his teeth). It must be unlikely he went back to navvying.

Mayhew met the other man in a Vagrants' Refuge in Cripplegate where down-and-outs could stay for three nights at a time, but no longer. They slept in rows of trays, like open coffins, with dressed sheepskins called basils for bedclothes. The navvy, a big flaxen haired man in a short blue smock, yellowed with clay, had first gone navvying as a nipper on the Liverpool-Manchester and had been cheated by truckmasters and hags ever since. A few weeks back he'd hurt his leg on the London-York but, because the bone was unbroken, he got nothing from his Sick Club.

'I went to a lodging house in the Borough,' he told Mayhew, 'and I sold all my things — shovel and grafting tool and all, to have a meal of food. When all my things was gone, I didn't know where to go. One of my mates told me of this Refuge, and I have been here two nights. All that I've had to eat since then is the bread night and morning they give us here. This will be the last night I shall have to stop here, and after that I don't know what I shall do.'

'Ever since I was nine years old,' the navvy ended, 'I've got my own living, but now I'm dead beat, though I'm only twenty-eight next Augustust.'

It wasn't until 1903 that Mrs Garnett was able to revive the old idea of pensions for navvies and do something about it. Even then, only men over sixty-five who could prove they had worked on public works since boyhood qualified. Single men got five shillings a week — married men, seven and six — the barest needed to keep them out of the workhouse and in lodgings in a navvy hut.

Contractors provided the money although, as with most things she undertook, Mrs Garnett had to bully them. 'I am very grieved,' she wrote in Decemberember, 1906, 'to inform you no more old navvies can be put on this fund — I know it is very hard for the twenty who have been rejected, and we were hoping for a bit more fire and food this bitter weather — many of them born navvies and now worn out! The sons who enjoy the positions and wealth earned by their fathers' ability and the men's work, do not (mostly) help, and newer firms forget these old Pensioners who have worked for them in past years. The hard fact is, the gentlemen who so nobly give, helping not exclusively their own old workmen, but those of all other contractors, cannot do any more.' Nevertheless by 1914 the fund had cared for over two hundred old people and by 1916 had paid out £20,000. [43/44]

For those who couldn't get a pension, hawking was one of the very few ways to keep out of the workhouse with any dignity, and it was always popular with the elderly and ill. 'Our chaps are very good,' an eighty-one year old navvy told Mrs Garnett, 'and all our landladies would buy a two or three needles and sich.'

In the '50s os the wife of an alcoholic navvy on the Lune valley railway in Westmorland kept her family alive by selling paper fly-cages to farmers in the old fortified halls and hill farms between the Lune and Eden. In 1911 the Letter told its readers Richard Smith was a genuine case — ill-health had stopped him navvying and he was now an organ grinder. In 1930 Charlie Ward, born and bred a navvy, was sightless and selling matches in Penge until he got a small pension from the Society for the Blind.

Being free was essential to navvies and every old hawker counted himself luckier than people locked in workhouses and asylums. Blind Billy, a quiet and humble man, had one almost sightless eye when he reached the Lindley Wood dam in the '70s. He had become a navvy when he found his wife was a prostitute and he couldn't bear it. Mrs Garnett sent him to Leeds Infirmary where his bad eye was blinded and his good eye damaged. At first Bowers, the works manager, gave him light work around the dam — road-mending, stone breaking, sand riddling — until he could barely see at all. Mrs Garnett then set him up as a tea hawker, walking around the farms and navvy huts, until the dam was finished. Then he was locked away in Henshaw's Blind Asylum in Manchester to learn basket-weaving, something his clumsy navvy hands wouldn't let him do. He was jailed in the asylum, allowed out once a month if he could find a guide, until he died some years later in misery.

Mrs Annie Phelps got somebody to write to the Letter in 1909. She was blind and in the workhouse and wanted her husband, Gloucester, to fetch her. Gloucester, a man of about forty with light blue eyes, a fair complexion and fair hair cut in a fringe, was last seen in the Rotherhithe tunnel in 1903, the year Annie Phelps went blind. She had three brothers: Giant, Sammy Spragham, Fat Spragham.

Annie Phelps wrote to the Letter again in 1912, this time from Gloucester workhouse. Now she was twice-trapped: double-locked in blindness and the blank, blind workhouse, dun and dingy, sharp with the smell of carbolic and institutionalised poverty. She wrote for the last time in 1914 from the same place. Probably she died there, the worst death a navvy could face, blind, infirm, imprisoned.

Sources

[Note: Full citations for works cited by the name of the author or a short title can be found in the bibliography.]

MacGill and the death upon the railway is from Children of the Dead End. The statistics comparing navvy mortality to that of soldiers in the Napoleonic War are from Chadwick's Papers. The comparison with the Boer War is from Annual Meeting Speeches (Sir John Jackson). Statistics elsewhere are either from Mrs Garnett or have been worked out from the dead and hurt lists published by the Navvy Mission Society.

The Sapperton accident is from the Gloucester Journal 22 January 1787: that at Strood is from Simm's Public Works. What happened at the Eston cutting is from Our Navvies. The London-Birmingham men with smallpox thick upon them is from Chadwick's Papers. Cholera at Woodhead is from John Dransfield's book History of Penistone, 1906. Epidemics on the Dore-Chinlev are from Quarterly Letter to Navvies 55, March 1892. Typhoid and The mass-accident at Ince is from the Daily Graphic 20 July 1891 et seq.

The Didcot-Newbury hospital is from Our Navvies. Hospitals on dams are from Quarterly Letter to Navvies — hereafter cited as NL — 25, September 1884. The MSC Accident Service is from Sir Harry Platt's article "Canal Accident Service" in the Port of Manchester Review, 1968.

Soup kitchens on dams are from various editions of the Quarterly Letter to Navvies. That people were dying of hunger at the Vrynwy dam is from the Shropshire and Montgomeryshire Post 20 March 1886.

Distress at Hull is from the Hull Packet 18 July 1884 et seq, and NL 25, September 1884, and NL 27, March 1885. The whole story is retold in Mrs Sleight's obituary, NL 81, September 1898, which is also the source of Walker's observation. What happened at Tilbury is from the East and West India Dock Company's Minute Book No 50.

The Rainy Day Fund was suggested in NL 27, March 1885. What happened to it is from NL 28, June 1885. What happened on the Christchurch-Bournemouth is from NL 29, September 1885. What happened at Blackheath is from NL 120, June 1908.

What happened when the Navvy Mission Society delegation met John Burns is from NL 123, March 1909. Material about the 1907 Bill is from Parliamentary Papers: Bills, Public 1907 IV, 915. The Bishop of London and the Society for the Suppression of Vice is from the London Dock Company's Court of Directors' Minute Book, 1804. Navvy attitude to work relief schemes is from the Report of the Royal Commission on the Poor Laws and Relief of Distress, 1909.

Katie Marsh asked and answered her question in English Hearts. Brassey asked and answered his in Work and Wages. The man who expected to die in a hedge bottom is from NL 83, March 1899. Telford's recommendations are from PRO RAIL 808/1. That Firbank's men need not fear white hairs is from NL 33, September 1886. Walker's Fragments are from Leech. The man who prized loyalty is from the Ship Canal News 1 February 1891. Sam Hall is from the same source, 22 October 1889. The Craven well-sinkers are from Our Navvies.

The idea of navvy pensions was floated in NL 99, March 1903. How much the fund had paid by 1916 is from NL 154, December 1916. Mrs Garnett's tirade against the firms who did not pay is from NL 114, December 1906.

The navvy who said our chaps are very good is from NL 83, March 1899. The wife who sold fly papers is from Payers. Richard Smith, genuine case, is from NL 131, March 1911. Charlie Ward is from NL January 1930. Blind Billy is from March 1909: NL 136, June 1912: June 1914. Blind Billy is from Our Navvies. Annie Phelps is from NL 123, March 1909: Quarterly Letters 136, June 1912: Quarterly 138, December 1912: and NL 144,

Last modified 19 April 2006