idely publicized excavations of ancient objects and their steady flow into the museums of Britain stoked Victorians' interest in archaeology. Wealthy enthusiasts treated archaeological finds as ornaments that testified to their owners' sophistication. The obelisk seized in 1818 by William Bankes at Philae and installed, after a long delay and at great expense, at Kingston Lacy, his Dorset estate, provides one notable example (Sebba 71-83; 97-98; 141-148); the Egyptian sarcophagus of Seti I, lodged at the bottom of a vertiginous and dramatically top-lit central void of the townhouse belonging to the architect Sir John Soane (1753-1837), and still glittering with traces of its original gilt, provides another (Dorey 30-32). Nor were ordinary Victorians excluded, as spectacular reconstructions of recently excavated sites and artifacts provided them with opportunities to transport themselves imaginatively into antiquity. When the Crystal Palace re-opened at Sydenham in 1854, for example, it featured reconstructions of celebrated ancient edifices, such as the temple at Abu Simbel, inspired and informed by recent discoveries and advised by luminaries like Layard (Pearson xiii).

The Crystal Palace was, in some ways, merely the physical instantiation of a craze for antiquity that had a more modest source, the popular press. In 1856, The Imperial Gazeteer ran a series on the archaeological highlights of Egypt, and Century Magazine also routinely featured stories about Egypt with historical and archaeological elements around this time. Perhaps no writer on the antiquities beat was more prolific than Amelia Edwards (1831-1892), who published an enormous number of articles -- more than seventy alone in the London Times -- extolling Flinders Petrie’s finds in Egypt while promoting the work of the Egypt Exploration Fund, which she not only founded but also funded with fees earned from her lecture tours. The associated visuals could be astounding, as in the dramatically sun-lit scenes from Schliemann's excavations at Mycenae published in 1877 in the Illustrated London News. The Gentleman’s Magazine and Leisure Hour also ran features on archaeological sites of interest, particularly in Britain. Spiced with references to dangers posed to travelers by from unfamiliar flora and fauna, not to mention locals whose welcome was not always warm, travelers’ accounts stoked yet more interest in archaeology, usually represented in an adventurous fashion that romanticized the hardships of archaeological excavation and the heroism of the excavators. And there were popular novels: Edward G.D. Bulwer-Lytton's triple-decker evoking The Last Days of Pompeii (1834), for instance, dramatized -- and in so doing, organized -- historical relationships between the antique civilizations of Rome, Greece, and Egypt while inviting his readers to engage with broader Victorian concerns about the nature of authenticity and the value of original artifacts versus spectacular copies, such as the reproductions featured in the Crystal Palace.

Outside London, municipal and provincial museums played an important role in bringing archaeology into wide awareness. The transfer of artifacts to these smaller museums was part of a program, promoted most strongly by Flinders Petrie and his sponsors through the Egypt Exploration Fund, that sought on the one hand, to seed enthusiasm for archaeology widely throughout Britain and on the other, to focus attention on the kinds of artifacts -- small, portable, not especially striking -- that were easiest to remove from distant sites. Despite the breathless reverence with which Petrie’s systematicity in excavation is usually described, his primary aim was not merely to anatomize the context of an excavated object but to select objects that would be of particular interest to specific museums, particularly smaller ones outside London (Stevenson 32). By keeping the museum in view as the object’s final destination, Petrie permitted the interests of these museums to structure his selection of objects and in fact subordinated systematic excavation to the interests of the acquiring museum:

Here lies, then, the great value of systematic and strict excavation, in the obtaining of a scale of comparison by which to arrange and date the various objects we already possess. [...] The aim, then, in excavating should be to obtain and preserve such specimens in particular as may serve as keys to the collections already existing (qtd. in Stevenson, p. 32).

Interestingly, recipients of Petrie's shipments did not always find them as valuable or useful as Petrie apparently expected them to. In his capacity as the British Museum’s Keeper of Greek and Roman Antiquities, Charles Newton judged one of Petrie’s shipments, from Naukratis, so “ugly” he simply threw it away (qtd. in Stevenson, p. 35).

The archaeology of the Holy Land proved especially popular because of the way these excavations helped to bring familiar Biblical scenes and stories to vivid life. In The Thrones and Palaces of Babylon and Nineveh (1876), for instance, JP Newman enthused over Birs Nimrud, believed to be the most visible fragment of the remains of the Tower of Babel: “Rising suddenly out of the desert plain, a riven, fragmentary, blasted pile, and standing out against the sky, without another prominent object near to relieve the view, its solitary appearance was strangely impressive … Such was the enchanting power of the vision, that the eye was transfixed, and the spell of history was upon the soul" (qtd. in Larsen, p. 47).

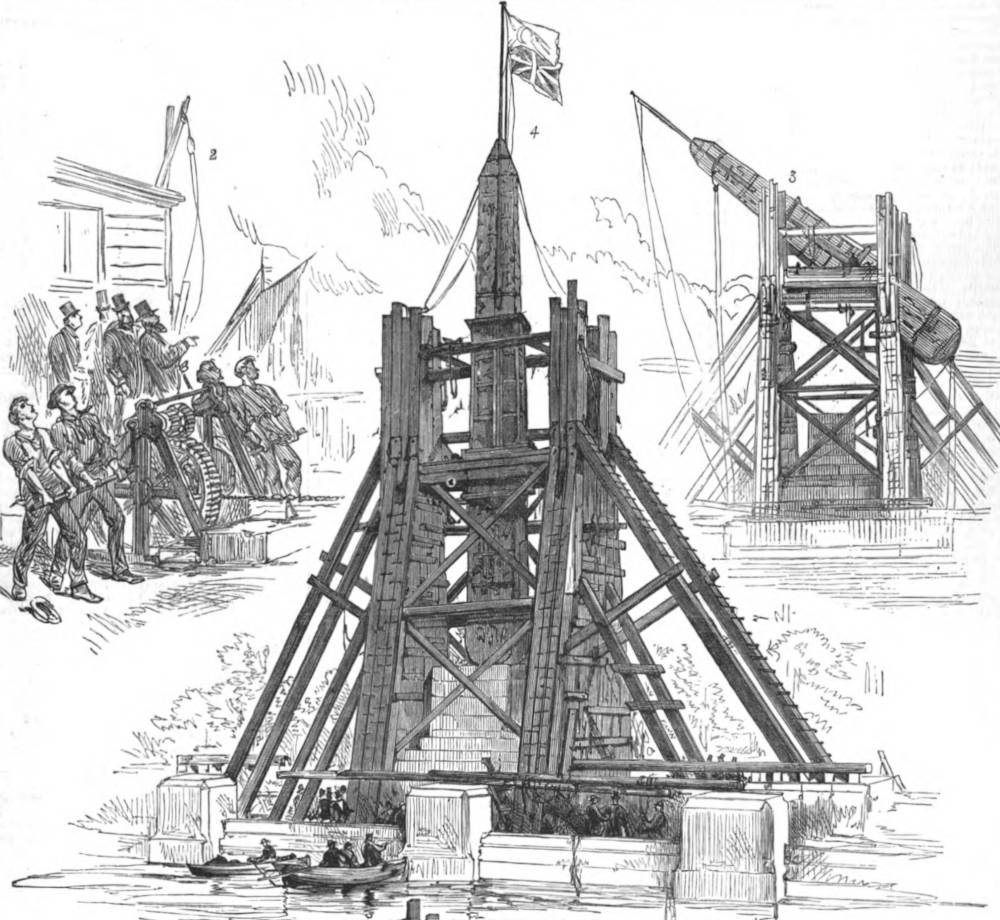

Left: The Egyptian Hall, Piccadilly. Right: Raising Cleopatra’s Needle on the Thames Embankment (1878). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Victorian Egyptomania appeared in a variety of contexts, from privately owned trinkets to architecture on the grandest public scale (Carrott, pp. 31-37). Its effects could be seen on London's streets throughout the century, from the Egyptian Hall at Piccadilly, built in 1811-1812, to the Egyptianized bas-reliefs ornamenting a building at Cockspur Street one hundred years later. Obelisks were a favorite public ornament, as evinced by the excitement surrounding the installation of an obelisk known as Cleopatra’s Needle on the Thames Embankment in 1878. Thanks to the promotional efforts of Sir James Alexander, a soldier and explorer, moving the obelisk from Alexandria became a cause celébrè, but all the publicity would have availed nothing without the deep pockets of his partner, Sir Erasmus Wilson, a wealthy dermatologist. Their collaboration demonstrated what could be done when private and public interests merged, that is, when “private citizens [were] driven by their imaginings of what the state ought to do, rather than the state itself.” (Curran et al., p. 259)

Visual art powerfully conveyed images of archaeological excavations that linked the sites and monuments with larger structures of feeling and imagination, much with a particularly religious bent. At the turn of the nineteenth century, the closure of much of Continental Europe drove wealthy British visual artists to find alternatives to the Grand Tour; the less well-off, such as Joseph Bonomi, accompanied travelers to Egypt and the Levant in order to document their finds. Regardless of how they got there, these artists returned with portfolios full of images that broadened Victorians' store of visual knowledge of antiquity. The spread of British influence in Egypt, Mesopotamia, and other areas of archaeological interest enhanced this trend. The artist David Roberts (1796-1864), for instance, documented his extensive travels in Egypt and the Levant in a series of watercolors of both the major architectural ruins and ordinary scenes of daily life and published them in a sumptuous edition. Working in a slightly different vein, still other artists focused on reproducing paintings of archaeological significance, as did Christina Herringham with the Ajanta frescoes in western India.

The popularity of archaeology in turn increased the general salience of mythological and Biblical themes, which Victorian artists freely incorporated into their work. Examples include the classically-inspired paintings of Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1836-1912) and paintings by John Collier (1850-1934) of figures from ancient history, notably female figures of ambiguous intent such as Lilith, pictured with a snake; and Clytemnestra, wife of the Greek commander Agamemnon, whom she murdered. The figure of the Sphinx remained a popular subject for painters as well as a potent source of meaning for writers as various as Thomas Carlyle, Thomas De Quincy, Sheridan Le Fanu, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and Oscar Wilde. Victorian archaeological mania also provided fine matter for satire, and artists such as Lady Dufferin documented its excesses with tongue lodged firmly in cheek.

Victorian Archaeology

- Introduction

- Excavators, Artifacts, Politics

- Beyond Heroic Narratives and Splendid Artifacts

- Archaeology as a Discipline

- Bibliography

Related Material

Bibliography

Carrott, Richard G. The Egyptian Revival: Its Sources, Monuments, and Meanings, 1808-1858. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1978.

Curran, Brian and Anthony Grafton, Pamela O. Long, and Benjamin Weiss. Obelisk: A History. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009.

Dorey, Helen. "Sir John Soane’s Acquisition of the Sarcophagus of Seti I." The Georgian Group Journal 1 (1991): 26-35.

Larsen, Mogens Trolle. The Conquest of Assyria: Excavations in an Antique Land. New York and London: Routledge, 1994.

Pearson, Richard, ed. Victorians and the Ancient World. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Press, 2006.

Sebba, Anne. The Exiled Collector: William Bankes and the Making of an English Country House. London: John Murray, 2004.

Stevenson, Alice. Scattered Finds: Archaeology, Egyptology, and Museums. London: UCL Press, 2019.

Last modified 14 August 2021