In transcribing the following paragraphs from the Internet Archive online version of The Imperial Gazetteer’s entry on Egypt I have divided the long entry into separate documents, expanded abbreviations for easier reading, and added paragraphing and links to material in the Victorian Web. I have also added the illustrations by David Roberts, which appeared a decade before the Gazetteer, and the almost exactly contemporaneous photographs by Francis Frith. — George P. Landow

s the Arabic language has been for 12 centuries the language of Egypt, the literature of this country necessarily merges in the wide sea of Arabian literature. There, as in other Mahometan countries, the Koran is the only book systematically studied. In the schools, indeed, established by Mahommed Ali for specific purposes, and placed under the direction of Franks, suitable texts of various kinds were indispensible, and these have been generally supplied by translating from the French. The modern Egyptians have as yet acquired, and but partially acquired, the first elements of science.

It is not improbable that from the time of the Macedonian conquest, nine centuries and a half before the Arab invasion, the Egyptian language began to give way to the Greek, losing its literary cultivation, though it remained in vulgar use. The introduction of Christianity naturally favoured the inroads of the Greek language, and it is not surprising that the Coptic language, in the specimens remaining to us, should exhibit a large intermixture of foreign words. After the Arabs were settled in Egypt, the Coptic continued to be cherished only by a small and despised sect, and it ceased to be a living language, it is supposed, in the 12th century. Coptic literature belongs to the Christian period, and is almost wholly theological. If, therefore, we would look for the truly indigenous literature of Egypt that literary cultivation which belonged to the country when its historical importance was at its height, we must seek it in the graven monuments of that period. But as the description of those wonderful monuments belongs properly to topography, we shall here confine ourselves to such a brief and general review of them, as will serve to indicate the chief epochs of the history which they record, and the cultivation of the people.

Passing over the 25,000 years during which Egypt was ruled by gods and demigods, we come to the mortal Menes, the founder of the first of 30 dynasties, recorded more or less perfectly by Manetho, the high-priest of Isis et Sebennytus, who lived about 300 B.C. But so arbitrarily has the high priest’s information been dealt with by the writers who have handed it down to us, and who have sought to adapt it to their own theories, that we cannot decide whether he places Menes 5400 or 3900 years before the Christian era. However, it is worthy of remark, that the son and successor of Menes is said to have written a book on anatomy, and to have had a temple at Memphis. This city was already, under the second dynasty, the capital of the kingdom; and mention is made, at the same early age, of Bubastos or Pu-Pasht (Pibeseth, Ezek. images/28 9. 17), dedicated to the goddess Pasht, the remains of which may still be traced at Tel-Bastah, on the East side of the Delta.

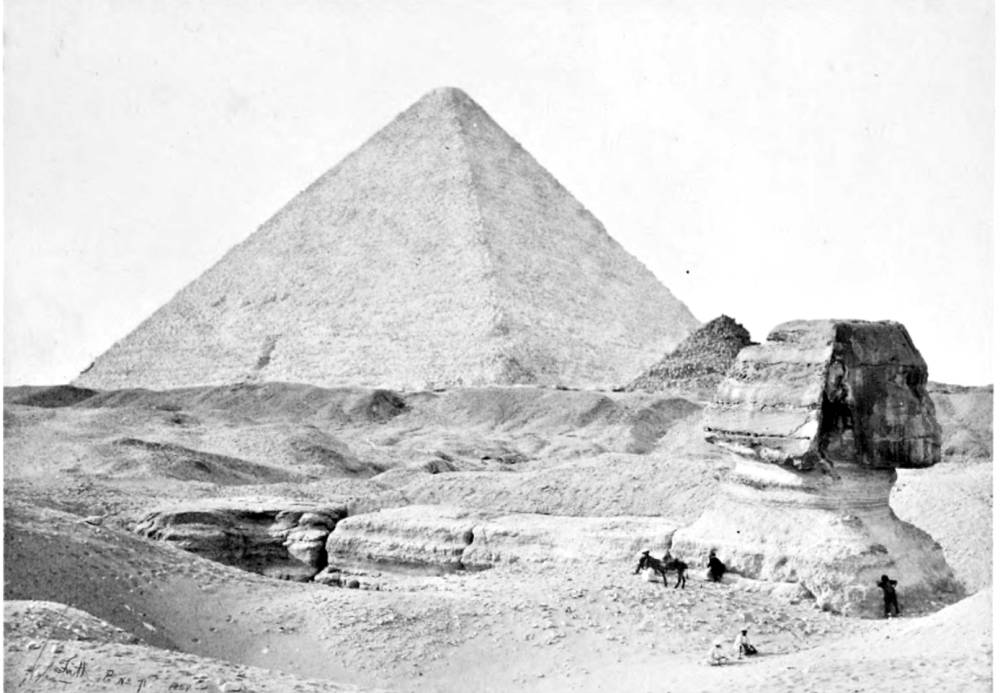

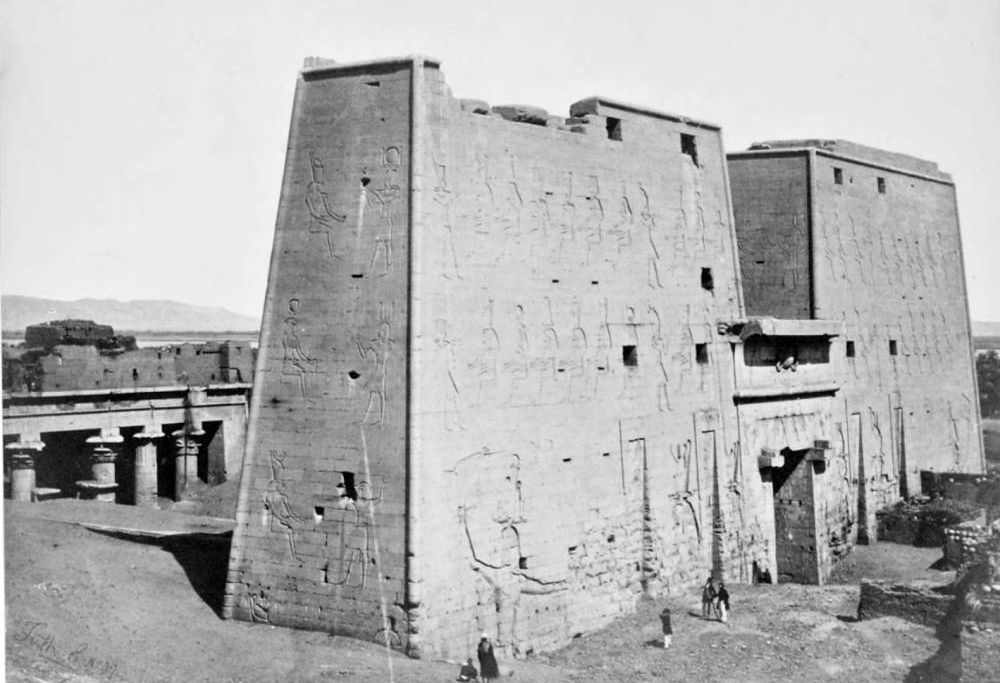

Two of Francis Frith’s photographs from Egypt and Palestine (1858). Left: The Sphinx and Great Pyramid, Geezeh. Right: The Great Pylon at Edfou. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

With the fourth dynasty begins the period of undoubted contemporary monuments. Shuúfo (Cheops) built the great pyramid, in which his name is written; his immediate successor built the second; and his nephew, Menkare, the third. A portion of the coffin of Mcnkare, with his name inscribed on it, is now in the British Museum, being probably the oldest specimen of writing extant beyond the pyramids and the tombs of Gízeh and Sakkara. These earliest known specimens of hieroglyphic writing exhibit the art in complete maturity, and, coupled with the pyramids, prove that Egypt, under the fourth dynasty, was already far advanced beyond the infancy of civilization. The 11th dynasty was the first of the Diospolitan or Theban kings, whose celebrity, however, commenced with the 12th, to which belonged Sesortasen, one of those kings whose achievements have been heaped on the half fabulous Sesostris; and of whom there remains an inscribed pillar recording his conquests in Nubia, and his son Ammenemes III., who embanked Lake Moeris, and built the labyrinth. This edifice, the foundations of which may be still traced, appeared to the Greeks, even while Karnak stood in all its glory, to be the greatest and most wonderful in the world.

Left: Karnac. Right: Karnac. Both by David Roberts, R.A. Signed with the name of the artist and lithographer, Louis Haghe. From Eygpt and Nubia. 1842. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

The memorials of this distinguished dynasty are written or graven on the walls in the grottoes of Beni Hassen. The 15th and two succeeding dynasties were those of the Hyksos or shepherds, whose tyrannous rule continued for some centuries. These shepherds, that is, pastoral, and comparatively rude tribes, appear to have been the Canaanites, who, on their expulsion from Egypt, founded Jerusalem. With the 18th dynasty begins the most brilliant period of Egyptian history, and the greatness of Thebes.

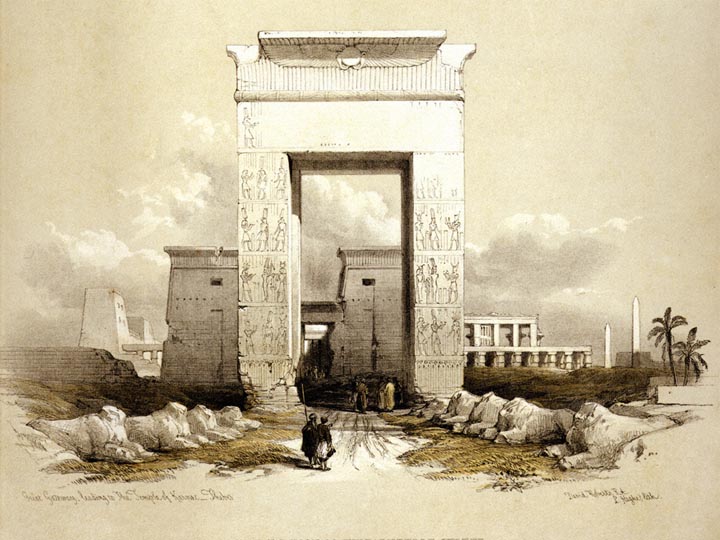

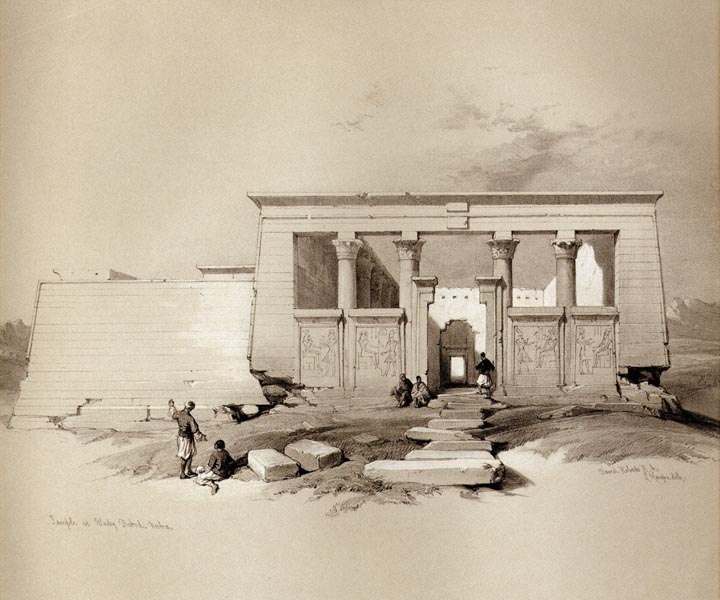

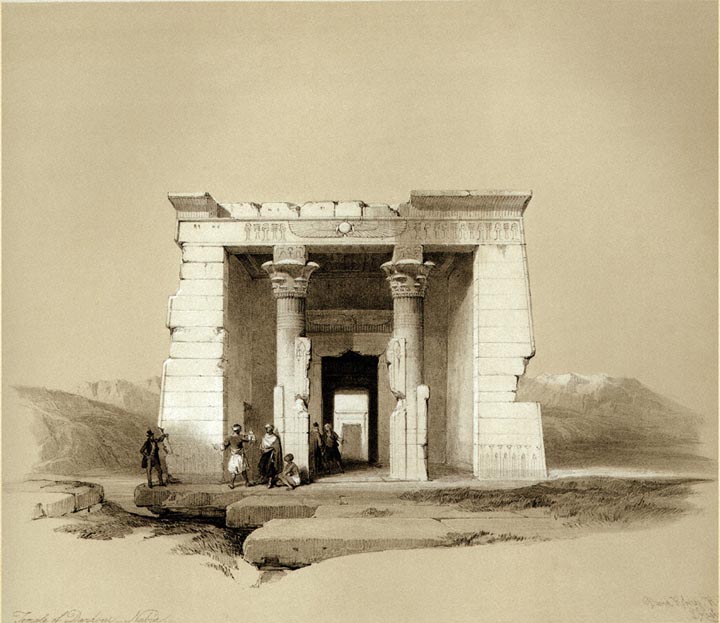

Left: Temple at Wady Dabod, Nubia. Right: Great Gateway leading to the Temple of Karnac, Thebes. Both by David Roberts, R.A. Signed with the name of the artist and lithographer, Louis Haghe. From Eygpt and Nubia. 1842. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Aahmes (Amosis), the first king of the 18th dynasty, is supposed by some to have been the Pharaoh (Ph-re, king), under whom the Exodus took place; though others suppose the Exodus to have taken place in the reign of Ramses (Sesostris), the last king, or last but one of this dynasty.

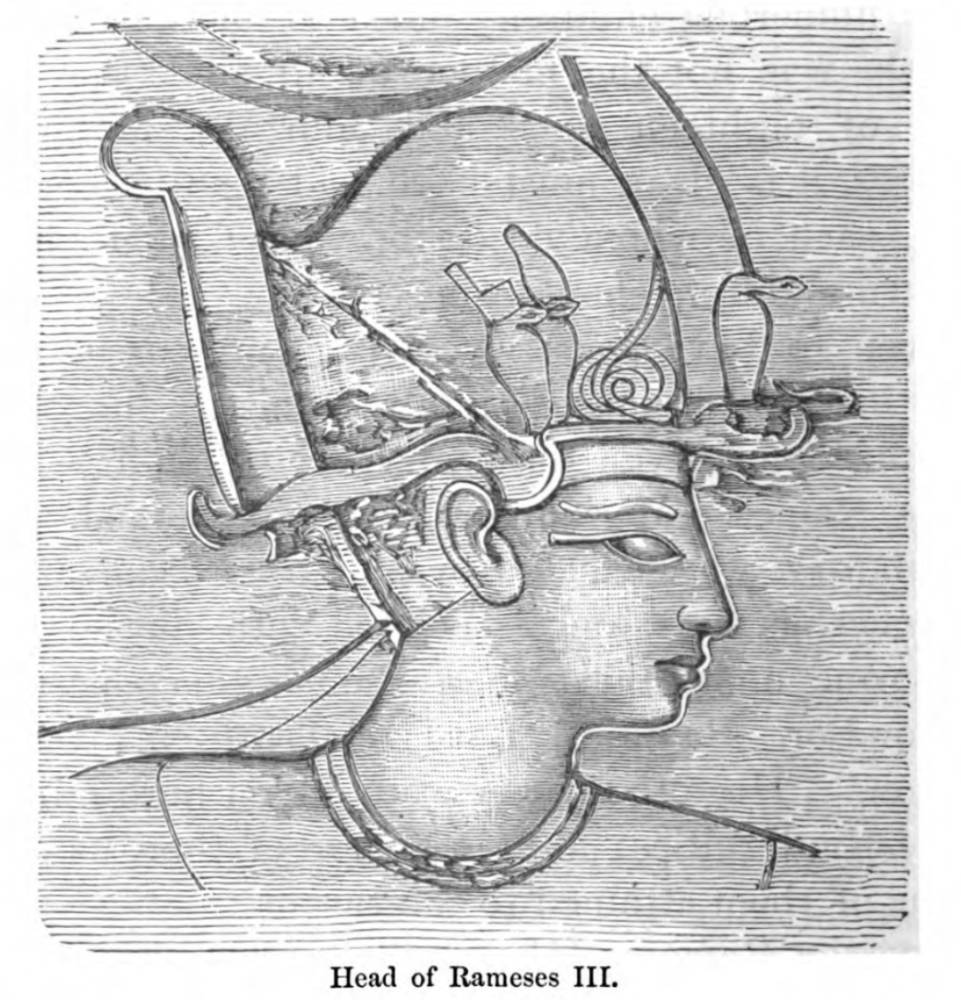

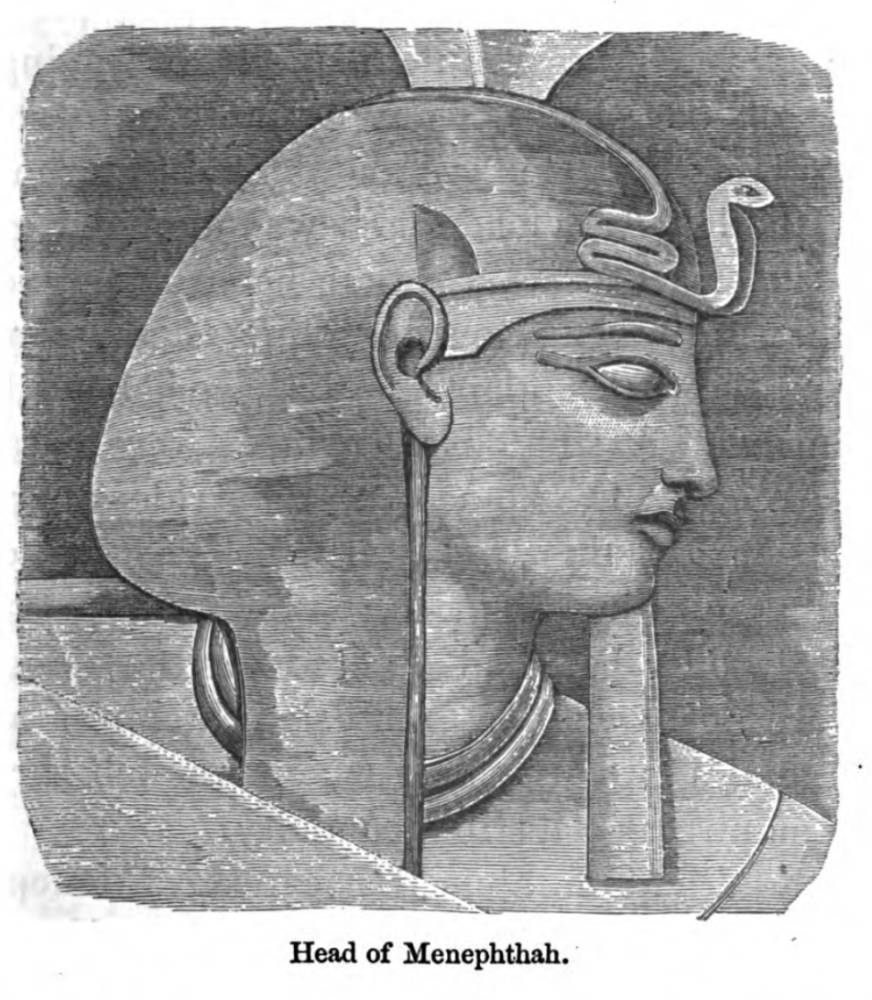

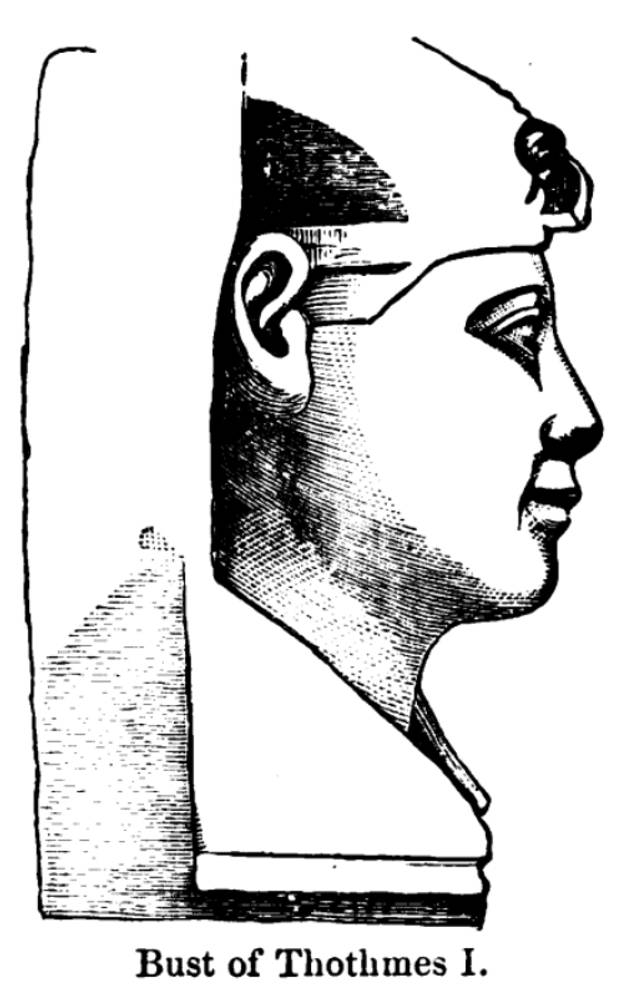

Ancient Portraits of Egyptian Pharaohs. From Rawlinson. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Subsequently comes a series of great princes Amenoph, Thothmes, Horus, Ramses, and Menephthah, to whom are due the grand monuments of Karnak, Luxor (el-Akhsar), Medinet Abu, Amada, Semneh, &c. The inscriptions of these victorious kings are found at the present day from Syria (at the Nahr-el-Kelb), to Jebel Barkal, above Dongola in Nubia.

Left: Temple at Wady Dabod, Nubia. Right: Temple of Dandour, Numbia. Both by David Roberts, R.A. Signed with the name of the artist and lithographer, Louis Haghe. From Eygpt and Nubia. 1842. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Their conquests are recounted on obelisks, temples, tombs, and represented by paintings, with hieroglyphic explanations, so elaborate and frequent, as to furnish the material of a voluminous, though still obscure literature. The tombs of the 12th dynasty are, many of them, in the valley named Biban-el-Mulúk (Gates of the Kings), extending in subterranean chambers, with painted or inscribed walls, to a distance, in some instances, of 350 feet ome papyri, written in the reign of Menephthah II., the last of this dynasty (and son of Ramses III., the Sesostris of most writers 1340 B.C.), have been partially interpreted, and throw a curious light on the manners of the age. One of them contains instructions written by a minister of state for the secret preparation of a certain feast, whence it appears that the Ethiopian feast, entitled Table of the Sun (in old Egyptian phrase, the King), as described by Herodotus 800 years later, had its origin in Thebes.

Under the 20th dynasty began the decline of Egypt and of Egyptian art, while Assyria, on the other hand, now rose. A Pharaoh, probably the last, of the 21st dynasty (Tanites, by Isaiah called the princes of Zoan), gave his daughter in marriage to King Solomon (1 Kings ix. 16). The 22d began with Sesonchis, the Shishak of Scripture (the first Pharaoh mentioned by name in the Sacred Volume), to whom Jeroboam fled, and who afterwards sacked Jerusalem. In the paintings at Karnak, which represent his conquests, this event is shown in detail, and the written title, King of the Jews, points out the principal captive.

The next dynasty was founded by Sabaco (So, the ally of Hosea, 2 Kings xvii. 4), originally from Upper Nubia. His name, as well as that of his follower Tirhaka, or Zerach the Ethiopian, is found on the monuments. The 26th dynasty is distinguished chiefly by Psammetichus, in whose reign the Greeks began to grow numerous in Egypt. This was followed by the Persian Cambyses and his successors for 124 years, after which period we have again three dynasties of native princes, the last king of Egyptian race being Nectanebus, of whom there remains a temple and inscription at Philae. He was driven from the throne in 341 B.C. by a usurper, who was soon after displaced by Darius Ochus; and he in turn was obliged, in 332 B.C., to make way for Alexander. [2.912]

Left: The Island of Philæ by Sunset. Right: Island of Philæ, looking down the Nile. Both by David Roberts, R.A. Signed with the name of the artist and lithographer, Louis Haghe. From Eygpt and Nubia. 1842. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Bibliography

Blackie, Walker Graham. The Imperial Gazetteer: A General Dictionary of Geography, Physical, Political, Statistical and Descriptive. 4 vols. London: Blackie & Son, 1856. Internet Archive. Inline version of a copy in the University of California Library. Web. 31 July 2020.

Frith, Francis. Egypt and Palestine. 2 vols. London: James S. Virtue, 1858-1859. Hathi Trust Digital Library online version of a copy at the Getty Research Institute. Web. 3 August 2020.

Rawlinson, George. History of Ancient Egypt. 2 vols. New York: Dodd, Mead & Co., 1880. Online version from the Hathi Trust Digital Library of a copy in the New York Public Library. Web. 4 August 2020.

Last modified 1 August 2020