urveys of Victorian archaeology typically begin with the early excavators and the sites and artefacts that have come to be associated with their names. Of these perhaps the most prominent was Austen Henry Layard (1815-1894), the adventurer who, gazing at a series of impressively large grassy mounds rising up from the earth outside Baghdad in April 1840, had a hunch that he might find whole cities concealed within them (Larsen 9).

Five years later, in 1845, after having obtained the support of local officials and the celebrated Assyriologist Henry Rawlinson, Layard uncovered the remains of the ancient city of Nimrud; soon after that, he found Nineveh (Waterfield 40-49).

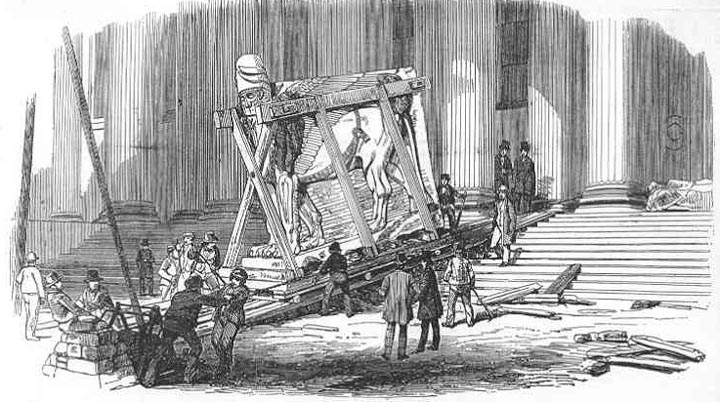

"Amongst the recent arrivals from Nimroud, the most striking and important is a colossal Lion, the weight of which is upwards of ten tons. — The Illustrated London News.

Artefacts from those excavations were later shipped in fifty cases to the British Museum (and a number of smaller objects found their way into a wedding gift from Layard to his wife, a necklace in which a number of cuneiform seals were embedded). In February of 1852, Layard’s discoveries -- including huge sculptures of lions and bulls with wings and human heads, -- were reported in the Illustrated London News. Hailed as a hero and showered with accolades, Layard took his story to a wide public, entertaining audiences with tales of his activities in Mesopotamia, which he eventually memorialized in several well-received books including the bestselling Nineveh and its Remains, published in 1849 (Malley 155).

Although there was no clear path to archaeology as a profession in these early days, Layard did at least provide a template for how to go about the work. His influence is discernable in the career, for instance, of Nathan Davis (1812-1882), a clergyman stationed in north Africa whose archaeological career hewed closely to Layard’s example. From 1856 to 1859, Davis excavated more than than thirty Roman mosaics and a number of Phoenecian inscriptions at Carthage (modern Tunis). He shipped these materials in fifty-eight cases to the British Museum, where they can still be seen, and he memorialized his excavations in several illustrated volumes, including Carthage and Her Remains (1861), a title obviously inspired by Layard’s earlier publication; as well as articles for the Illustrated London News. A gregarious host, Davis entertained a series of prominent guests—who could be relied upon to talk up his work—at his renovated palace outside Tunis. These guests included Lady Jane Franklin (1791-1875), who had become a celebrity in the course of her efforts to discover what happened to her husband Sir John Franklin’s ill-fated Arctic expedition; and the French novelist Gustave Flaubert (1821-1880), who modeled one of his characters in Salammbô (1862) on a worker he observed in the Davis household (Freed 68-73).

The classical archaeologist Arthur Evans (1851-1941) developed similarly. An indifferent student of history at Oxford, Evans spent his early adulthood pursuing adventures in and around the declining Ottoman Empire. During a stint as a journalist, he wrote an account of his travels, Through Bosnia and Herzegovina, which appeared in 1876 and 1877. In 1884, he was appointed Keeper of the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford, to which he organized the transfer of many archaeological artifacts. Viewed through the lens of the standard heroic narrative of Victorian archaeology, all of this activity was merely preparatory to the work that secured his fame. Following the death of his wife, Margaret, he became sufficiently interested in Crete to secure a monopoly on all permits needed to excavate there. He and his crew began to dig; in 1900, he uncovered an ancient palace at Knossos, the first evidence of ancient Minoan civilization.

As these examples suggest, early Victorian archaeology was undertaken by enthusiasts rather than specialists with extensive training in methods and techniques. Some early excavators were adventurers like Layard; others, like Davis, were employed by missionary societies to staff their outposts in North Africa, Egypt, and the Levant. Still others were soldiers, like Duncan McPherson (1812-1867), a medical doctor serving in Crimea on the Black Sea who was responsible for securing any archeological finds he might uncover while setting up field hospitals (Freed 16). Indeed, Victorian archaeological projects were often linked the shaping of foreign policy and the projection of British imperial power. Members of the military and diplomatic corps pursued archaeological work alongside their official activities or as part of them. This was not, or not just, mere spadework by random enthusiasts. Additional examples of archeology as an imperial extramural would include excavations Henry Creswick Rawlinson (1810-1895) in Persia and by Alexander Cunningham (1814-1893) in India.

Ancient objects, especially large and impressive ones, were natural targets of enthusiasm. But the seizure, relocation, and display of these objects were also potent sources of national pride. The nations of Europe had long competed to find and secure the most impressive relics of antique civilizations and to install them in museums and other public places as highly visible testaments to their own power. In the first decades of the nineteenth century, the transport, and sale of monumental antiquities such as the Dendera Zodiac in Paris and the Elgin Marbles in London followed a model for future acquisitions that amounted, in Freed's pithy formulation, to “licensed plunder” (16). Foreign governments recognized the threat and sought ways to limit the removal of antiquities from within their borders. In 1837, for instance, newly independent Greece prohibited the export of antiquities. Passing through Athens in 1856, Charles Newton (1816–94), who excavated the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus, observed, somewhat disingenuously, that the law was mainly honored in the breach (Freed 16).

Dr. Schliemann, The Explorer of Troy and Mycenæ

From The Illustrated London News.

As the agents of acquisition of these prestigious objects, early Victorian archaeological excavators were routinely cast as folk heroes in popular accounts, often with nationalist and imperialist overtones. (Breeze 95-103) That most were not university-trained specialists in archaeology only added to their appeal. For instance, Heinrich Schliemann (1822-1880) -- the Mecklenberg tycoon who, in the late 1860s, famously took time off from cornering various markets in order to search for ancient sites like Troy using only his volumes of Homer -- was presented as a natural archaeological genius. Writing for the Illustrated London News one journalist observed, “His example at the present time appears more worthy of note, from the circumstance that he is not a man trained to the profession of literary and academic scholarship.” This genius was not only opposed to elite university education, which emphasized ancient languages, but also distinctly British. Thus the author approvingly highlighted Schliemann's lack of academic qualifications, noting that “he has never been a professor of any of the German or other Universities,” a pointed allusion to scholars, mainly on the Continent, who worked within traditions of classical studies and Biblical criticism requiring, at a minimum, knowledge of Latin, Greek, and Hebrew.

Excavations in Egypt presented a distinctly complex political problem due to the difficulties of sharing power both with local Ottoman rulers and with rival French forces who had a long-established beachhead there. Even after the British had partially seized control of Egypt, the Service des Antiquités de l'Égypte, the administrative department for archaeology, continued under French control (and would remain so until the middle of the twentieth century). This arrangement had profound consequences for British archaeology in Egypt. By limiting excavations in the more familiar and easier-to-reach sites in the Nile Valley, the bureau's French directors -- including even Gaston Maspero, who was of all of them the most well disposed toward the British -- effectively forced British archaeologists to search for excavation sites further afield, adding to the risk, difficulty, and expense of their projects (Stevenson 39-42; Gange 174).

Fantasies of antiquity, and the related impulse to uncover elements of these fantasies in the real world by digging them out of the ground, permeated the highest levels of political, military, and diplomatic activity. The celebrity of Schliemann, for example, could not have arisen without the parallel adventuring of no less a figure than William Gladstone, whose “Homeric obsession” only seemed to find a satisfactory outlet when he was playing Agamemnon or Ajax in contested Eastern territories. In this way Gladstone “gave Schliemann’s discoveries … meanings that were rarely attached to them outside the English-speaking world” (Gange 143-44).

Victorian Archaeology

- Introduction to Victorian Archaeology

- Beyond Heroic Narratives and Splendid Artifacts

- Archaeology in Victorian Popular Culture and Visual Art

- Archaeology as a Discipline

- Bibliography

Bibliography

Adkins, Lesley. Empires of the Plain: Henry Rawlinson and the Lost Languages of Babylon. London: Harper Perennial, 2004.

Breeze, D. J. "Archaeological Nationalism as Defined by Law in Britain," in Nationalism and Archaeology. Edited by John A. Atkinson, Iain Banks, and Jerry O'Sullivan. Glasgow: Cruithne Press, 1996.

Freed, Joann. Bringing Carthage Home: The Excavations of Nathan Davis, 1856-1859. Oxford and Oakville: Oxbow Books, 2011.

Gange, David. Dialogues with the Dead: Egyptology in British Culture and Religion, 1822-1922. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Larsen, Mogens Trolle. The Conquest of Assyria: Excavations in an Antique Land. New York and London: Routledge, 1994.

Josefowicz, Diane. "The Whig Interpretation of Homer." In Ann Blair and Anja-Silvia Goeing, eds., For the Sake of Learning: Essays in Honor of Anthony Grafton, vol. 2. Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2016. 821-844.

Malley, Shawn. "Austen Henry Layard and the Periodical Press: Middle Eastern Archaeology and the Excavation of Cultural Identity in Mid-Nineteenth Century Britain." Victorian Review 22.2 (Winter 1996): 152-170.

Waterfield, Gordon. Layard of Nineveh. London: John Murray, 1963.

Last modified 13 August 2021