he interest in archeological excavation which so strongly affected the decorative arts of the nineteenth century provided the inspiration for the design of some of the most characteristically Victorian jewellery; in spite of the fact that the origins of this style are almost wholly classical in the best eighteenth century tradition there is no possibility of confusing the 'Egyptian' style of the fifties and sixties, or the bijoux étrusques which became widely popular in France and England in the seventies, with the classical style of the late eighteenth century or the Regency.

Napoleon's Egyptian campaign was responsible for the revival of interest in the Egyptian style which had been popular in the eighteenth century, and for providing a mass of illustrated information about Egyptian art. Many of the Egyptian motifs used in decoration in the eighteenth century had been taken from the Recueil d'Antiquités égyptiennes, étrusques, greques et romaines, by the Comte de Caylus (1752) or from Piranesi's Diverse Maniere d'adornare i camini (1766) but these designs were almost completely fantastic. Some jewellery purporting to be ancient Egyptian was confected from similarly unreliable sources before the turn of the century and was accepted as such for many years after the publication of the material from the excavations had exposed the inaccuracy of technique and decoration. The Egyptian style, like the Greek and Roman styles, was based on archeolo'gical research. It was the Napoleonic campaign and the subsequent excavations by l'Institute de l'Egypte, whose findings are recorded in the twenty-two volumes of the Description de l'Egypte (1809 to 1828) which, with Baron Vivant-Denon's Voyage dans la Basse et Haute Egypte (1802), provided much of the information on which the nineteenth century Egyptian style is [103/105] based. Jewellery decorated with lotus plants, scarabs, and hieroglyphs remained popular until the seventies and eighties.

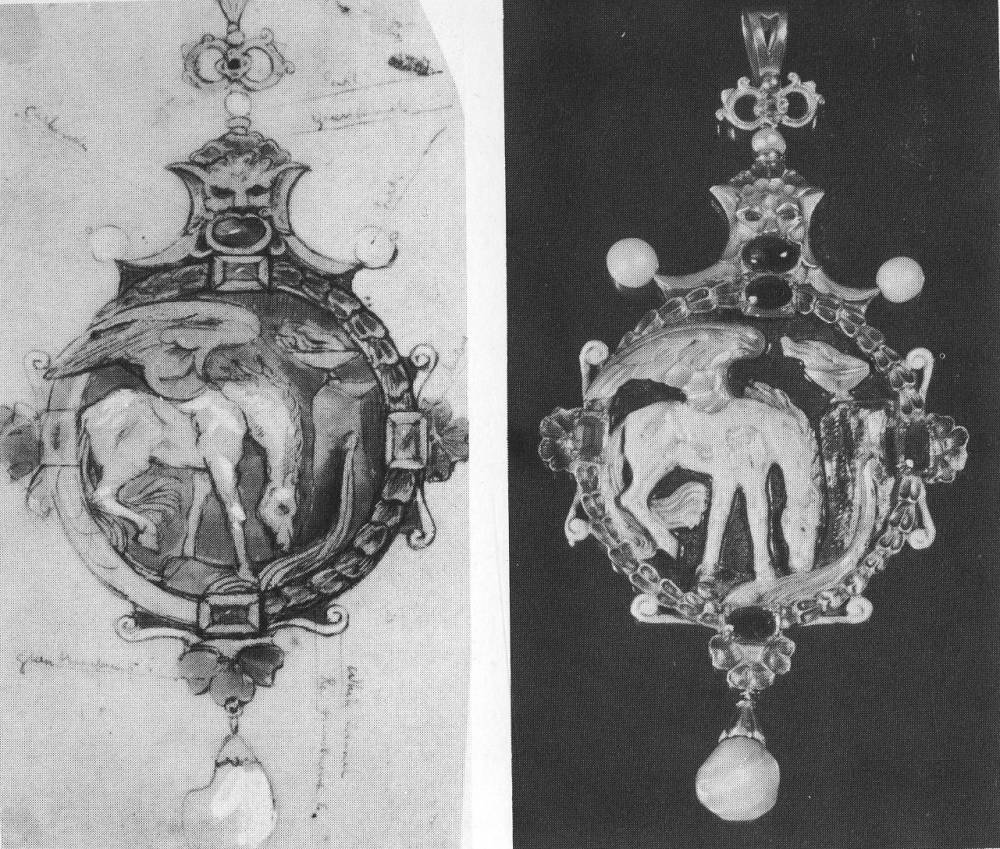

The most popular nineteenth century fashion of indisputably classical inspiration is the cameo jewellery which was worn from the early years of the century until the eighties (Plate 39; see below. Plate 38 see left column). The standard of quality was extremely uneven, but the best cameos, though less exquisite than the antique or renaissance carved gems which they were copied from, were still impressive in their fine detail.

Plate 39. Tiara in gold with onyx cameo, of the 'Toilet of Nausicaa.' Italian, mid-nineteenth century. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Ethel Weil Worgelt.

Emperor Napoleon III conceived the idea of commissioning from Ingres a design for a great cameo that would rival, in size and complexity, the Grandes Camées of antiquity, one of the most famous of which, the Grande Camée de la Chapelle Royale, was in the Cabinet des Medailles of the Bibliotheque Nationale. The subject chosen was the Apotheosis of Napoleon, and the design was taken from the ceiling representing the same subject which Ingres had painted in the Salon de l'Empereur of the Hôtel de Ville in Paris (destroyed by fire in 1871), which the Emperor had seen and admired in Ingres' studio in 1854. Ingres made a drawing for the cameo using exactly the same irregular oval shape as the Grande Camee de la Chapelle Royale, whose subject is the Glorification of Germanicus.

In spite of the curious shape of this design and the way the background is filled in with a sepia wash which is intended to imitate1 sardonyx (see Plate 40 in left column), this drawing was at one time thought to be a study for the ceiling in the Hotel de Ville. In 1859 Adolphe David, the gem-engraver, was chosen to carry out this ambitious project. After a search lasting tor three years a suitable stone was found, a piece of sardonyx, rather smaller than the Grande Camée, 24cms. high and 22cms. wide, and in 1861 the work of engraving the stone, which was not completed for thirteen years, was begun. The finished cameo is a mere shadow of Ingres' bold and complex drawing; much of the original [106/107] design had to be abandoned in the process of cutting the stone, a whole group is missing from the lower part, and though the main lines of the design have been adhered to much of the detail is lost as well. It is possible that Ingres' design was unsuitable for the purpose, but one is forced to conclude that the nineteenth century craftsmen were unable to rival the skill of the engravers of antiquity, although one persistent nineteenth century tradition held that the best of their modern cameos were indistinguishable from antique or Renaissance gems. This apparently ludicrous belief is given substance in one instance at least by a curious story about the work of the gem-engraver, Benedetto Pistrucci, quoted in Romilly's Cambridge Diary, 1832-1842, referring to an incident which took place in December 1836:

Fri. 9 ... Then to E.T. Hamilton to meet his uncle W.R Hamilton, Cockercll, Willis, Peacock & Whewell & Heavisidc W.R. Hamilton showed us a brooch with an exquisite head ol Flora cut in alto relievo by Pistrucci: this is the work he executed to prove a similar head (bought by Payne Knight in italy & by him pronounced an antique & as such left to the British Museum) his own work.'

Payne Knight had aquired the 'Flora' gem, for which he paid £500, from the dealer Bonclli, who had himself bought it from Pistrucci for only £5. Pistrucci's association with Bonelli had lasted for some time before he discovered the use to which his engraved gems were being put, and from then on he attempted to safeguard his work by marking the stones in a secret place. Bonelli had been in the habit of removing Pistrucci's signature from the gems and substituting a Greek one before selling the work as an antique cameo, so he decided that he should end this unsatisfactory association, and he made his way to England where, he found a friend and patron in the influential Sir Joseph Banks. He was at the house of Sir Joseph Banks working on a portrait of him when Payne Knight arrived eager to show Sir Joseph 'the finest Greek cameo in existence'. Pistrucci asked if he might see it and was astonished to be shown one of his own works. Payne Knight steadfastly refused to believe Pistrucci's claim that the 'Flora' gem was by him, and remained unconvinced by all the evidence produced to prove it (including, presumably, the second 'Flora' cut by Pistrucci); it was even pointed out to him that the [107/108] roses used in the design were not known in ancient Greece, but he stuck firmly to his belief that he had bought a fine antique gem and he presented it to the British Museum.

Pistrucci was employed as the chief engraver at the Royal Mint, an unusual honour for a foreigner, and his designs can be seen on the coinage of the period; the head of George III was taken from a jasper cameo portrait which he had made of the king for Sir Joseph Banks, and the beautiful St George and the Dragon which appeared on the reverse of the crown was designed and executed by him. Pistrucci's daughter, Eliza, was also a gem-engraver, and her work was shown at the International Exhibition in London in 1862, a sardonyx cameo of the Death of Adonis.

Both 'Egyptian' and 'Etruscan' jewellery enjoyed a longer period of popularity than the 'Algerian' jewels which became fashionable during the French campaign in North Africa and enjoyed a period of popularity in the forties. These were jewels decorated with Moorish arabesques, with pendants in the shape of beads or acorns depending from them, as well as line gold fringes and loops and swags of fine chain, which must have looked well with the burnouse, an evening cloak with short sleeves and a hood decorated with a tassel which was fashionable at the time. The fringes and chains were used long after the Algerian mania had subsided and the Moorish decoration had been dropped.

At the end of the forties further excavations in the Near East were completed and in 1848 Sir Austen Henry Layard published Nineveh and its Remains, an account of his excavations in the ancient capital of Assyria, in which his discoveries were illustrated and described in detail. Assyrian sculptures were the inspiration for all kinds of jewellery and 'Assyrian' jewellery was shown in the Great Exhibition of 1851 by Garrard and Co., now the Crown Jewellers, who exhibited a 'Bracelet in polished gold, with ruby and brilliant circular centre — from the Nineveh sculptures', and Hunt and Roskell whose exhibit included 'Specimens of earrings, in emeralds, diamonds, carbuncles, &c., alter the marbles from Nineveh'.

Plate 41. Set of jewellery made from Assyrian or Babylonian cylinder seals, mounted in gold in imitation of Assyrian jewellery. Designed by Sir Austen Henry Layard for his wife and made by Robert Phillips 1869. Reproduced courtesy of the British Museum.

The jewellery devised by Layard for his wife (Plate 41) is made of Assyrian or Baby-Ionian cylinder seals from the excavations set in gold work in imitation of Assyrian jewellery done by Robert Phillips.1 The activities of the Napoleonic scholars in Italy and Egypt and Layard in Nineveh had provided a basis of [108/109] accurate information on which a more realistic approach to the design of antique jewellery could be based, and the designers of the mid-nineteenth century, once the delicate techniques of the Etruscans and Greeks had been mastered, were often content simply to reproduce the jewellery discovered in the extensive excavations which were being carried out at this time. Much of the archeologically-inspired jewellery which was made in Italy during the nineteenth century was designed for the stream of travellers who followed in the footsteps of the eighteenth-century Grand Tourists, visiting the art centres of Italy and happily acquiring the delicate mosaic jewellery, the cameos in stone, shell or lava, and the carved coral which were abundantly available. Mosaic reproductions of the wall-paintings at Pompeii and views of the classical remains of Rome and Naples set in gold decorated with [109/110] filigree (see Plates 7c & 116) were very popular in the early nineteenth century but by the sixties much of the work, like the Florentine pietra dura, had become rather coarse, and the energies of the Italian goldsmiths were by this time almost entirely centred on the reproduction and re-interpretation of classical goldsmith's work, the manufacture of which spread to France and England in the sixties and seventies, providing an extraordinary contrast to the prevailing fashion of the day, which favoured the most lavish possible use of diamonds in almost invisible settings.

Although the fashion for Italian archeological jewellery did not really catch the public imagination in this country to any great extent until the late sixties and seventies, the excavations in Egypt and Assyria had already begun to have their influence on jewellery design at the time of the 1851 Exhibition and archeology was having a strong effect on design for the theatre by the late forties and fifties. Charles Kean's production of Sardanapalus in 1853 had the most lavish scenery based on Layard's discoveries at Nineveh, the decorations of the palace being taken from the Assyrian sculptures which had so recently been added to the collections at the British Museum. Two more of Kean's productions in the fifties relied on recent archeological excavations for the authentic details of the scenery and costumes, his Winter's Tale (1856) set in the time of Pericles and Midsummer Night's Dream (also 1856) were both lavishly costumed in 'authentic' Greek robes, even the tools in Quince's workshop being taken from the genuine articles recently discovered in the excavations at Herculaneum. The same attention to period detail was paid to the jewellery and many of the motifs that were to become commonplace in the fashionable jewellery of the next two decades were first seen on the stage (Plate 56); the archeological details are incorporated into the design regardless of accuracy or suitability.

Like the Assyrian discoveries which had been made by an Englishman, the treasures excavated in this country were far more rapidly assimilated by British (a term used to include the Irish, as in the Official Catalogue of the 1851 Exhibition) jewellery designers in the classical styles which derived from the jewellery inspired by the treasures which Layard brought back from Nineveh; the ancient 'Celtic' style was very much in evidence at the Great Exhibition, being the main contribution of Scottish and [110/111] Irish exhibitors, such as Messrs. Waterhouse of Dublin, who

have contributed the various specimens of BROOCHES which appear on this page. [Art Journal Illustrated Catalogue, 1851, p.20]. They are all, more or less, remarkable, as well for the peculiarity of their character, as for their history, and the ability shown in their fabrication. They are, in fact, copies of the most curious antique brooches which have been found in Ireland, and are preserved in the museum of the Royal Irish Academy and elsewhere. The largest and finest of the series, 'the royal Tara brooch', has been recently discovered near Drogheda, it is of bronze ornamented with niello and gems, and is the most remarkable work of the kind that has yet been procured. In these objects, Messrs. Waterhouse have been singularly successful; the great beauty of their works cannot fail to insure their extensive popularity.'

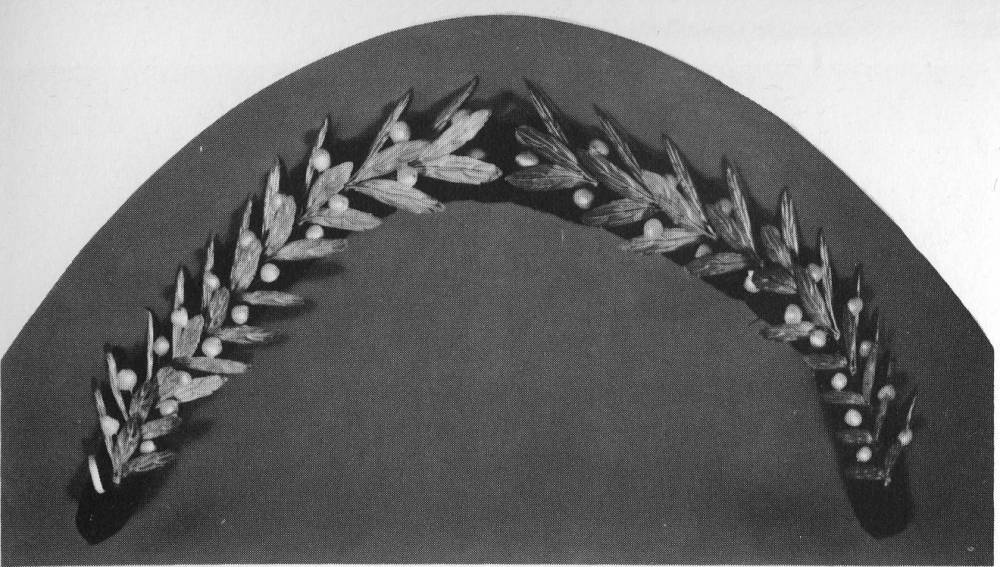

This Celtic style, which was so popular in England in the mid-nineteenth century, unlike the Celtic revival at the turn of the century, failed to make anything but a very modified impact on the wider European fashion scene, and its manufacture remained almost exclusively in the hands of the Scottish and Irish jewellers who had revived it, unlike the Italian Archeological style as exemplified by the work of the Castellanis and the Neapolitan goldsmith, Giacinto Melillo (1845-1915) whose influence spread throughout Europe and America. The various historical styles of jewellery, such as mediaeval or Gothic, Archeological (which included the revived Celtic style as well as Etruscan, Greek, Roman, Egyptian and Assyrian) or Renaissance, were frequently chosen for the design of presentation pieces like the Gothic bracelet decorated with scenes from the life of St Louis made by Froment-Meurice to be presented to the Contesse de Chambord, and the shield-like brooch made by Mr West of Dublin, who used the same source of inspiration for his designs as his compatriot, Waterhouse, to be presented to Helen Faucit by the people of Dublin, which were both shown in the Great Exhibition in 1851. The laurel wreath, in the shape of an Etruscan funerary diadem, designed for Fanny Ceritto (Plate 42) was ordered from the Roman jeweller Serretti by a group of noblemen who occupied one of the proscenium boxes at the Teatro Alibert in Rome for her benefit performance at the end of the season in [111/112] the autumn of 1843. The tiara, which is of gold set with a large emerald and two rubies, can be seen in the portrait of Fanny Ceritto commissioned by the famous chef, Alexis Soyer, from the Flemish artist, F. Simoneau, who was his wife's step-father. The tiara is sitting on the table on the right hand side of the picture, in its case which is inscribed 'Gli ammiratori a Fanny Cerrito, Roma il22. Nov. 1843'.

Plate 42. Design for a tiara for Fanny Cerrito. Rome 1843. Courtesy of the Cooper-Hewitt Museum of Decorative Arts and Design, Smithsonian Institution. This tiara was made by the Roman jeweller, Serretti, and presented to Fanny Cerrito by a group of her admirers.

Although the period of its greatest popularity was from the latter half of the eighteen-sixties until the end of the eighties, this type of archeological jewellery, particularly of quasi-Etruscan design, was still being made at the turn of the century. The Russian goldsmith, Rouchomowsky, whose spectacular fakes gained ii'm a great deal of publicity was still exhibiting nco-Etruscan vork decorated with granulation beside the eclectic Art Nouveau productions of Lalique, whose work, incidentally, he enormously admired, and the American designs for necklaces of Brazilian beetles (Plate 59) done c.1900 incorporate motifs similar to those used by Eugene Fontenay for his 'Campana' jewels made in the [112/113] seventies. Apart from the granulated decoration which is the most remarkable feature of ancient Etruscan jewellery, the successful imitation of which became the ruling obsession of men like Castellani and Fontenay, the motifs chiefly used in the mid-century classical jewellery are those which are found in the neo-Grcek architecture and interior decoration of the time which can be found in pattern books like The Grammar of Ornament, by Owen Jones such as the ever-popular acanthus, the anthemion motif, the Greek key pattern, the Lotus, etc.

This archeological jewellery is goldsmith's work par excellence, employing as it does some of the most delicate and complicated techniques of this branch of jewellery making, and gems are used sparingly, if at all. When the gold jewels of the Etruscans were first brought to light in the early nineteenth century it was thought that it would be impossible to imitate the granulation which decorates them but the Roman goldsmith Fortunate Pio Castellani, who was present at the excavations in an advisory, capacity, dedicated himself to the revival of this lost art and it is his painstaking research that the later copyists of this style of jewellery owe their knowledge of the ancient techniques. Castellani would most strongly have disputed Matthew Digby-Wyatt's claim that these ancient jewels were 'executed by the simplest processes'. An account of the difficulties which attended this research for a satisfactory method of applying the minute granules of gold to the jewels is contained in the paper which Castellani's son read to the Archaeological Association in 1861, which gave a detailed resumé of the avenues which Castellani had explored in his attempt to penetrate the secrets of the Etruscan goldsmiths. Castellani had begun to imitate the jewellery from the excavated tombs in the 1820s, beginning by making simple copies of Roman jewels in filigree and gold in about 1826, but he was determined to reproduce the more elaborate Etruscan work and to this end began his researches into the history of jewellery technique, consulting the works of Pliny, Theophilus (the llth century Westphalian monk) and Cellini, but with no success. Eventually, after studying the traditional filigree work of India, Malta and Genoa, he happened upon the peasant craftsmen of the Italian Marches who were carrying on a tradition of jewellery-making which might have been in use since the time [113/114] of the Etruscan civilisation, and men and women from the small town of St Angelo in Vado were brought by him to Rome and set to imitating and reproducing the jewellery from, the newly opened tombs. The various technical problems being overcome in the course of time Castellani and his two sons, Alessandro and Augusto who carried on the business after his retirement, proceeded to manufacture the jewellery which was described by Vever as:

ce bijou étrusque en or très léger, a filigranes, lequel, apres avoir fait la fortune de son auteur et de ses descendants, constitua depuis une sorte de monopole, et devint presque un produit national pour l'Italie, supplantant le bijou Français jusque'alors presque seui en faveur dans la péinsule qui nous en fasait annuellement des achats considerables.'

These neo-Greek and Etruscan jewels were not destined to remain forever the sole prerogative of the Italians, by the sixties they were being extensively imitated in France and England and increasing liberties were being taken with the form and decoration of the antique originals. Castellani had neatly classified the different styles of the ancient work, dividing them into the following three categories:

'1. that made by the ancient inhabitants of Italy, such as the Etruscans; 2. that due to the Greek colonists of Southern Italy, to which division most probably the specimens in the Museo Bourbonico belong; and 3. that made in the Roman period, of which the articles found in Pompeii are examples.2

The subsequent copying of the Archeological jewellery of Castellani and the imitators of the Castellani style took less and less account of these fine distinctions and the later work bears little resemblance to the real jewellery from classical antiquitv which was by the seventies available for copying in museums in London — the British Museum bought a number of pieces from the Castellani collection in 1872 — Paris — where the jewellery from the famous collection of the Cavaliere Campana could be seen in the Louvre — and Rome, where the Capitoline Museum housed the collection made by Augusto Castellani after the Campana collection had gone to Paris.

Comparisons between the Archeological jewellery of the nineteenth century and the antique [114/115] pieces from which they derive show how great latitude was taken with the form and decoration of the modern work. Even in the case of direct copies there will usually be some anomaly of technique which betrays the origins of the piece in question, and the regularity and tidy finish of the modern work is not found in antique jewellery. There were certainly a large number of nineteenth-century fakes of antique jewellery, some possibly still undetected, as well as the well-known ones, such as the famous 'Tiara of Saitapharncs' and the pair of pendants also by the Russian jeweller Rouchomowsky which the Louvre acquired at the same time as the Tiara (Plate 58). Close in style to Greek work of the 4th century B.C., these pendants show the skill with which the techniques used in ancient jewellery could be imitated, but even here where the smallest details of technique have been attended to with infinite care, the decoration is taken from a variety of sources and to an expert in antique jewellery of this period these pendants would be immediately revealed as a fake. Neapolitan goldsmiths had been doing a thriving trade in copying and faking the jewellery unearthed at Pompeii or the Greek jewellery in the Museo Bourbonico (Plate 43) since the early years of the century [115/116] and spurious ancient jewellery was also made in a factory in the neighbourhood of Vienna where copies were made of jewellery dug up in the Crimea.

Plate 43. Copy of a necklace,= of the 6th-5th Century B.C. Neapolitan, early nineteenth Century. Courtesy of the British Museum.

A considerable hoard was discovered at Koul-Oba in the Crimea in September 1831 and bought by the Bibliotheque Imperiale in Paris in October of the same year. South Russia did in fact yield some remarkable treasures, most of which are now in the Hermitage, and for this reason the area provided the ideal location for Rouchomowsky's activities,

It is not uncommon to find the Castellanis mentioned in literature on nineteenth century antique jewellery fakes, but this reveals a misunderstanding of their actual position. Although some of the 'restoration' of the excavated jewellery was rather too thorough for modern taste. Fortunato Pio Castellani mainly used [116/117] his knowledge to create a new style and to enlarge the scope of contemporary jewellery design and very few of his jewels are copied unaltered from antique originals.

Plate 44. Necklace in amber and gold and left to right, fibula in gold, pendant in gold, pendant copied from a Scythian jewel, all by Castellani. Courtesy of the City museum and Art Gallery, Birmingham.

The Castellani family's own collection of antique jewellery provided endless inspiration, and it is rewarding to compare the work of the Castellani firm with the antique work which they knew intimately (Plates. 46 & 47) and with the work of their nineteenth century imitators such as Robert Phillips and his Italian proteges, Carlo Doria (Plate 51a) and Carlo Guiliano. The connection between Robert Phillips and Carlo Doria was established by the discovery (in the 'Oxfam' shop in Cheltenham) of the Castellani style bracelet shown on plate 51a, in [117/118] its Phillips box which was still in pristine condition. Some of the best of this Archeological jewellery was made by these three men and John Brogden of Watherston and Brogden who made the necklace and earrings shown in the 1867 Exhibition in Paris, now in the Victoria and Albert Museum. He also made 'Egyptian' jewellery decorated in this same style with filigree and granulation, and Assyrian jewellery with designs taken from the Nineveh sculptures. Mrs Haweis described the work of Phillips and Giuliano in The Art of Beauty:

Mr Giuliano of Piccadilly, and Messrs. Phillips of Cockspur Street, merit special notice for their artistic appreciation of good forms and good work. In the establishments of these gentlemen, who are most courteous in exhibiting their productions to artists and inquirers, work equal in technical ability to any of the old may be seen. Indeed, modern technical work actually excels the old, as I convinced myself one day at Mr Giuliano's, in a necklace of his own design and workmanship, worthy, for its beauty, of a place in a museum of art. The grain work (each grain being made in gold, and laid on separately, not imitated by frosting) was finer than any I ever saw.

A mass of less inspired work was turned out in the sixties and seventies — innumerable necklaces and earrings of pendant amphorae, acorns, stylized ears of corn and repoussée masks — and [118/119] it is sometimes confusing, when a decorative motif common to two or more of these archeological styles is used, to determine the actual source of inspiration. For instance the ubiquitous ram's head occurs in Greek, Roman & Assyrian jewellery but it can presumably be understood that the inspiration is Greek if gold amphorae depend from rings held in the mouths of the rams (earrings c.1870).

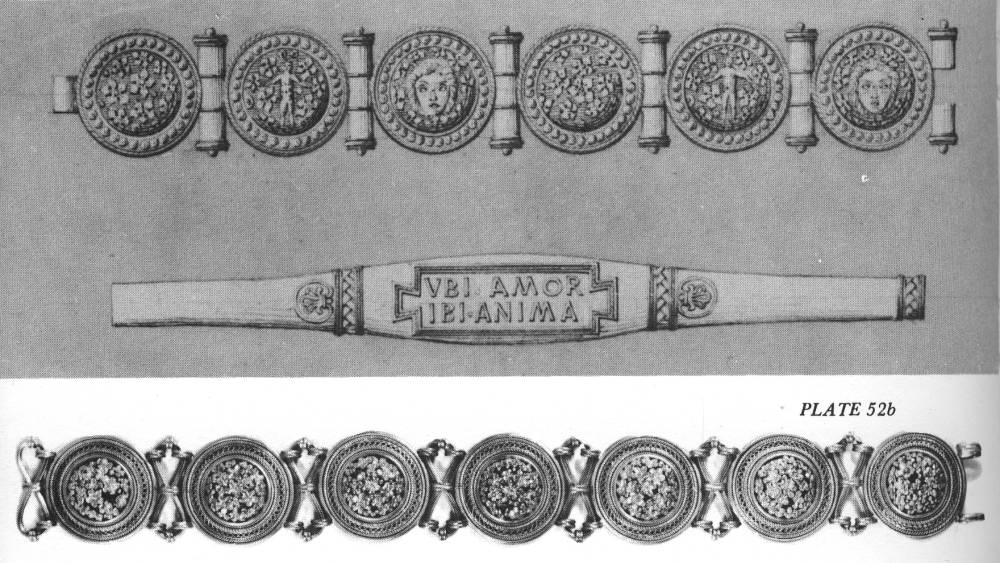

Latterly this confusion of styles became quite commonplace; the drawings in the Cooper-Hewitt Museum of Design (formerly Cooper Union Museum) by Augusto (?) Castellani (pi. 51c & 52a) probably done in the sixties, show how far the style of this jewellery has moved away from the Greco-Etruscan originals which were so faithfully imitated in the earlier work. In the seventies Eugene Fontenay (whose book Les Bijoux anciens et modernes, published in 1887, shows what an extensive and intimate knowledge he had of all styles of antique jewellery) was making jewellery in the Etruscan style inspired by the jewellery from the Campana collection which had been bought by Napoleon III in 1860. These 'Campana' jewels were shown in Paris in 1876 and enjoyed a great success but they too have departed from the Etruscan originals both in form and decoration.

It can be inferred that Fortunato Pio Castellani and his two sons were responsible for both the English and the French fashion for the Etruscan style since the date when these jewels were first made in London and in Paris coincides with the time when Augusto and Alessandro were forced to leave Italy on account of their political [119/120] sympathies, Augusto coming to London and Alessandro establishing himself in Paris, and it is through them that the secrets of Fortunate Pio Castellani's techniques were imparted to their English and French colleagues.

Diadem made by Castellani for the Countess of Crawford. c. 1875? Courtesy of the Victoria & Albert Museum. The design for the set of which this diadem forms part was suggested by the Castellanis' patron and collaborator, Michaelangelo Caetani, Duke of Sermoneta. In a report on the Paris Exhibition of 1867, W.G. Deeley of Birmingham describes:— 'a beautiful wreath for the hair like unto a laurel, . . . the berries were formed of selected pearls, the leaves of gold, nicely formed, and, in fact, about the best representation of nature I ever remember seeing' made by Castellani.

Throughout his researches Castellani had benefited from the archeological knowledge and enthusiastic interest of Michaelangelo Caetani, Duke of Sermoneta. Their association began in 1828 and the Duke's connection with the firm was to continue, even after the retirement of Fortunate Pio, with his sons Augusto and Alessandro, for about fifty years. Records of this long connection exist in the form of letters written by the Duke to both sons when they were abroad, which are preserved in the archives of the Palazzo Caetani, full of technical discussions and suggestions for designs. The letters are of particular interest in showing the continuing concern of the Duke and the Castcllanis themselves with the technical problems involved in making their chosen style of jewellery. Even in the sixties experiments still go on, as can be seen from this letter written by the Duke to Alessandro Castellani dated 1st March 1861:

[trans.] 'Apropos of Princess Mathilde, I enclose an artistic novelty that I have recently produced, which may also be of [120/121] some use to our jewellery work since it enobles malachite, which has been so misused by the unenterprising jewellers of the Via Condotti. [Practically all the malachite mined in Russia at this time was pre-empted by the Imperial family and this reference to Princess Mathilde probably means that the Duke obtained his malachite from her, through her husband, the Russian Count Anatole Dcmidoff owner of the famous Mcnorudiansk mine.] By turning it on the lathe, I have produced a number of buttons, which can be set in brooches and used in other ways, to give the effect of antique jewellery; for that reason I have used malachite that is uniform in colour, resembling turquoise, which looks like ancient copper or patinated bronze. Small round saucers [? "piccole patere"], nails, and ornamental bosses can be made from it. If you want to use these buttons you can easily design a setting for them. I believe that this method of turning soft stones is something new in jewellery. I have done the same thing with a turquoise of no great value, which was quite successful in a brooch, held by four long rings bent back from the circle which is behind; on each ring is placed [121/122] another [turquoise, presumably) which is closed with a little ball. Your brother has promised to send you at the same time a similar brooch, and here is a malachite worked bv me for you to study. So now malachite has been italianiscd - but there are other stones — and particularly strong stones in St Peter's, that don't want to be italianiscd!'

The last sentence contains a pun on 'pictra', stone, and S.Pietro, a joke which indicates that the Duke shared with Alessandro Castellani those liberal political views which forced Allesandro to leave Italy at this time.

Plate 51. Bracelet in gold made by Carlo Doria for Robert Phillips, c. 1865-1870. (51b) inset shows Doria's mark, a 'flew de lys' with monogram C.D. This style of bracelet was fashionable in the seventies. Courtesy of Oxfam Shop, Cheltenham.

The Duke's drawings are captioned with explanations of their purpose and their source of inspiration, one of these is 'A brooch of brilliants ordered by the Duke Cirella, which he wants to go with the tiara which has already been made for him.' Plate 54a has an inscription saying: 'This brooch with 5 turquoises is being made for an order which has been given to me. The design is taken from the ancient Clathri [Latin, a trellis or gate with bars] which we see in antique marbles. This kind of work helps to make the brooch large light and regular.' [123/124]

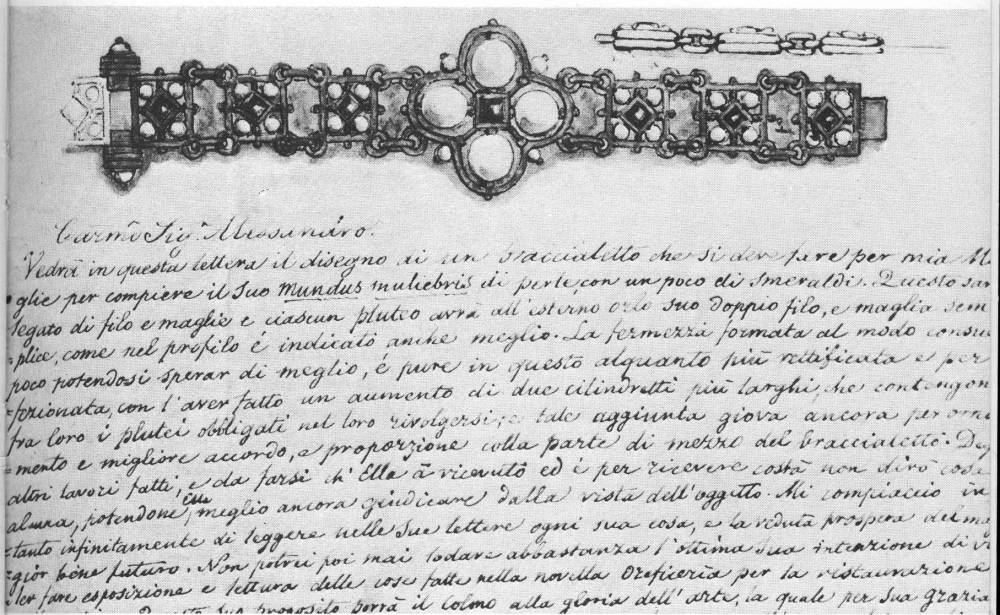

Another letter to Alessandro Castellani deals with the construction of a bracelet for which a design, done in pen and water-colour, is provided:

You will see in this letter the design for a bracelet which you will make if you can for my wife to complete her Mundus Muliebris [Latin, ornaments or dress of a womanj of pearls, with a few emeralds. These will be bound with wire and rings and each section will have a double wire on its outside edge, and a simple ring, which is shown even better in the side view.

The letter continues with the most minute instructions for the making of each part of the bracelet, the clasp, the larger central section and so on, every detail carefully considered.

More designs by the Duke of Sermoneta are collected in an album in the Palazzo Caetani archive entitled Disegni fatti per l'orefice Castellani, Michele Caetani, Duca di Sermoneta, which actually contains a miscellaneous collection of drawings of all subjects as well as the jewellery designs (see Plates 53 & 54b). Few of these designs are strictly classical, they are most like the two cruciform pendants made by Castellani in the Birmingham Museum (Plates 44 & 54a), but the suite of jewellery designed by him for the Countess of Crawford in the seventies is in the best tradition of the Archeological style (Plate 49).

Plate 53. Design for a bracelet with a letter written by Michaelangelo Caetani, Duke of Sermoneta, to Alessandro Castellani. Courtesy of the Archive of the Palazzo Caetani.

A letter from Augusto Castellani to the Duke dated 20th September 1875 reveals a more practical aspect of this long association:

Questo mattina ho preso finalement Ie onorificenze per la

mostra di Vienna ed unito a questa mia 1c manda il diploma e

la medaglia di cooperazione a Lei decretati pei miei oggetti

esposti. Augusto Castellani.' [125/126]

Top: Plate 52a. Two designs for bracelets by Augusta (?) Castellani. c. 1870. Courtesy of the Cooper-Hewitt Museum of Decorative Arts and Design, Smithsonian Institution. Bottom: Plate 52b: Gold bracelet by Castellani c. 1870. Courtesy of Howard Vaughan. This bracelet is a version of one of the designs on the preceding plate.

It is clear from this letter that the artistic 'cooperazione' between the Duke and the Castellani was recognized by the outside world.

Left: Plate 54a. Design for a brooch by Michaelangelo Caetani, Duke of Sermoneta. Courtesy of the Archive of the Palazzo Caetani. Right: Plate 54b. Pendant in mosaic and gold by Castellani. Courtesy of the City museum and Art Gallery, Birmingham.

The Exhibition in 1862 provided the first opportunity that most English people had had to see the Archeological copies, but anyone living in Italy could not fail to be concious of Castellani's work. A version of Castellani's technique is described by Robert Browning in The Ring and the Book and this passage contains the significant words 'Craftsmen instruct me' but the method of decorating the gold is not much like that described by Castellani; it does not emerge from the poem (hardly surprisingly) whether the instruction came from Signor Castellani or not. The passage begins with a description of the ring:—

'Do you see this Ring?

'Tis Rome-work, made to match

(By Castellani's imitative craft)

Etrurain circlets found, some happy morn,

After a dropping April.'

— and continues with a long exposition of the technique employed in making the ring.

The Brownings knew Castellani's work and had visited his workshop in 1859 to see the swords which were made by him for presentation to Napoleon III and Victor Emanuel, an occasion which is described by Elizabeth Browning in a letter to Miss E.F. Haworth:

You may have heard in the buzz of newspapers of certain presentation swords, subscribed for by twenty thousand Romans, at a franc each, and presented in homage and gratitude to Napoleon III and Victor Emanuel. Castellani of course was the artist, and the whole business had to be huddled up at the end, because of his holiness denouncing all such givers of gifts as traitors to the See. So just as the swords had to be packed up and disappear, some one came in a shut carriage to take me for a sight of these most exquisite works of art. It was five o'clock in the evening and raining, but not cold, so that the whole world here agreed it couldn't hurt me. I went with Robert therefore; we were received at Castellani's most flatteringly as poets and lovers of Italy; were asked for autographs; and returned in a blaze of glory and satisfaction, [127/128] to collapse (as far as I'm concerned) in a near approach to mortality.

Mrs Browning remarks that they were 'received ... as poets and lovers of Italy' so it seems likely that they became customers of Castcellani's subsequently, when they bought the ring which features in The Ring of the Book. A ring which belonged to Mrs Browning is now at Balliol College, Oxford, and is reputed to be the one described in the poem, but the evidence for this is conflicting This ring was presented to Balliol as the actual one from the poem, but in fact it bears a different inscription from the one which Mrs Browning always wore. Her son describes this ring as follows: 'The ring was a ring of Etruscan shape made by Castellani which my mother wore. On it are the letters AEI. After her death my father wore it on his watch-chain.' The ring which belongs to Balliol is made of soft, very pure gold, in an antique shape, but the letters on it spell VIS MEA. The portrait of Mrs Browning by M. Gordigiani shows her wearing five rings on one hand, none of them identifiable as the Balliol ring or the Castellani ring with AEI on it, but the portrait was painted in 1858, possibly before the ring was bought. This particular device AEI, which means always or for ever in Greek, was extremely [130/131] popular for Victorian sentimental jewellery of quasi-archeological design, and it is not too difficult to find such pieces now. These have been bought on occasion by Associated Electrical Industries to give to female members of their staff as retirement presents.

Egyptian-Style Necklace with Scarabs designed and manufactured by the Castellani workshop in Rome. 1860-69. Gold, steatite, lapis lazuli, L: 14 1/2 in. (36.83 cm). Collection: Walters Art Museum (Accession number: 57.1350). Reproduced courtesy of the Walters Art Museum. [Not in print edition.]

A parallel development in the revived Renaissance style introduced in the first half of the nineteenth century by Fauconnier and Froment-Meurice and already popular in the mid-nineteenth century was taking place at the same time as this archeological research, in almost every case by the same firms as those who were doing the pioneering work on the Greek and Etruscan techniques. The Renaissance style also comes mainly [130/132] within the province of the goldsmith, as here the priciple part of the design is carried out in gold and enamelled gold, with gemstones again used sparingly, presenting the same contrast to the fashionable diamond jewellery of the period. The use of enamel had been re-introduced into this country by A.N.W. Pugin, whose Gothic jewellery could have been compared with the remarkable Renaissance jewels, also in enamelled gold, by François Désirée Froment-Meurice, when they were both shown at the 1851 Exhibition. Both remarkable in their own very different way these jewels started the fashion for this type of (more or less) historically accurate mediaeval work which was to persist throughout the rest of the nineteenth century. Although neither of these men experimented with the archeological style, the Renaissance jewellery has an obvious affinity with this work and was well within the capacity of firms like Castellani, Robert Phillips, Carlo Giuliano and his sons and Watherston and Brogden, [132/134] with their interest in his )rical techniques and their experience of research.

Jewellery in the Etruscan style: Plate 59. Design for necklace American, c. 1900. The motifs taken from classical jewellery persisted in jewellery design until the turn of the century. Courtesy of the Cooper-Hewitt Museum of Decorative Arts and Design, Smithsonian Institution.

Plate 62. Designs for pendants in Neo-Renaissance style by Alfred Gilbert. Courtesy of Baron van Caloen.

Apart from the work of French jewellers like Froment-Meurice and Alphonse Fouquet (Plate 61b) the enamelled jewellery by Carlo Giuliano is unrivalled for its delicacy. Except in rare instances, such as the copies of Etruscan jewellery which were left by Giuliano's sons to the Victoria and Albert Museum, Giuliano avoided making exact copies of antique jewellery either from existing jewels or from pictures, and he developed an easily recognisable style which was difficult to imitate owing to the incredible delicacy of the enamelling (Plate 64)

The pendant by Giuliano on plate 64 was given to Marie Adeane, Maid of Honour to Queen Victoria, at the time of her [134/138] marriage to Bernard Mallet in 1891, by her mother-in-law. Lady Mallet. The pendant was designed to go with the sixteenth century Italian enamelled gold chain which it is hanging from in the uhotograph, the kind of commission which Giuliano was well suited to execute, both from the point of view of technical ability and design.

The extensive experience of enamelling techniques gained during the second half of the nineteenth century was to prove invaluable to the French jewellers of the fin-de-siècle. Capable of endless refinements of texture and colour the medium was ideally suited to this Renaissance jewellery by Giuliano, Castellani and Alphonse Fouquet. It is a highly delicate and specialised art usually reserved for an artist specially employed by the jeweller to carry out the necessary work which would then be mounted by a goldsmith. [135/136]

Left: Plate 65. Chatelaine with a watch in gold, platinum and diamonds by Hippolyte Téteger, c. 1890-1900. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum, New York (59.43a–c). Gift of Cele H. and William B. Rubinb 1959. Right: Plate 66. Pendant cross, silver, pearls and ebony. Designed by Edwin Lutyens in 1896, for Lady Emily Lytton, whom he married in 1897. Private collection.

As well as his well-known designs for the theatre, Charles Ricketts made a small number of designs for jewellery which he had made up for his friends, some of which are preserved in a sketchbook which is now in the British Museum, which is inscribed on the first page 'Designs for Jewellry [sic] done in Richmond 1899, C. Ricketts.' Some of the designs have a strong affinity with the work in the Art Nouveau style being done in France at the turn of the century by Vever, Lalique and Eugene Grasset but there are also renaissance designs in the same style as the Castellani pendant (Plate 60b), which has the characteristic lion's mask and enamel decoration. The design for the pendant, 'Pegasus drinking from the fountain of Hippocrene' (Plate. 63a; below) which was [137/138] made for Michael Field, has on it extensive notes on the stones to be used for the jewel, and the following inscription on it: 'executed for Michael Field to contain a miniature of Miss Cooper'.

Left: Plate 63a Design for a pendant by Charles Ricketts, 1899. Courtesy of the British Museum. Middle: Plate 63b. Pendant, from the design above. Gold, enamel, pearl and gemstones, made for 'Michael Field' (the pseudonym of the poets Catherine Bradley 1848-1914 and Edith Cooper 1862-1913). Courtesy of the Fitzwilliam Museum. Right: Plate 64. Pendant, zircon, blue, red and white in enamelled gold setting with four rose-diamonds made by Carlo Giuliano to go with the Italian Sixteenth Century chain of baroque pearls and blue, red and white enamelled gold. Given by Frances, Lady Mallet to her daughter-in-law, the Hon. Marie Adeane — one of Queen Victoria's maids-of-honour — at the time of her marriage to Bernard Mallet in 1891. Private collection.

Apropos of brief entry made by Ricketts in his journal on May 21st 1904: 'The jewel of bird for Mrs Binyon arrived, it was so hideous and clumsy that I was dumbfounded and depressed. We gave it to the model Esther Deacon.'3 This brooch was made by Giuliano, and it is very surprising that it should have so dissatisfied Ricketts. Later he appears to have employed H.G. Murphy.

T. Sturge Moore has added a note about the designing and making of the jewellery as follows:

'Ricketts kept a collection of precious stones in a drawer; after arranging a few on a piece of paper, he would design settings for them, with pen and water-colour, so finely and exquisitely that the goldsmith always failed to rise to the occasion. They thought it a point of honour that work should not easily break, but the old jewellery that Ricketts admired had broken only too easily. Wearers should be as flower-like as fairies, or circumspect as seraphs whose wings are all eyes. The delicacy he admired would have rivalled gold wreaths made for the dead, for whom economy as well as taste dictated a butterfly frailty. But Shannon calculated that over £100 had gone in a single year on gifts of jewellery, one piece alone having cost over £40, and Ricketts reluctantly admitted that this branch of design had better be given up.

Ruskin and William Morris would have found nothing surprising in Ricketts' dissatisfaction with the manufacturing jeweller of his time and would simply have urged him to master the arts of the goldsmith, the lapidary and the enameller so that he could realise their mediaevalising ideals and carry out the work himself. But Ricketts' difficulties in this respect are none-the-less rather surprising since the quality of all the fashionable Renaissance jewellery, by Carlo Giuliano in particular, is incredibly high, reaching a technical perfection which would have been respected even in eighteenth-century France. The enamelling provides a startling contrast in finish with the extensive experiments being made in this very, medium by followers of Morris and the artists connected with the Arts and Crafts Movement. [138/139]

28 February 2015