And if the disappointed author says to [his illustrator], "Why can't you draw like Phiz?" he can fairly retort: "Why don't you write like Dickens?" — George Du Maurier (qtd. in Golden 150)

In her latest book, Serials to the Graphic Novels: The Evolution of the Victorian Illustrated Book, Catherine J. Golden returns to one of her major interests, and traces the principal developments in illustrated fiction from the earliest illustrated serials of the 1830s to the graphic novels of the present age. Although she follows changes in both visual aesthetics and contexts of production over two centuries, her chief focus, as in her earliest book (Book Illustrated: Text, Image, and Culture, 1770-1930 [2000]) remains the collaborative works which resulted from the relationships between authors and artists. She has, then, necessarily restricted her scope to such pairings as Charles Dickens and Phiz (Hablot Knight Browne) in The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Society, and Lewis Carroll and Sir John Tenniel; and to the work of such individual writer-illustrators as William Makepeace Thackeray and George Du Maurier. Her approach in the final chapter, which deals with graphic novel adaptations of nineteenth-century British classics, is analogous, as she gives equal credit to the script-writer and artist(s) responsible for a collaborative project such as Batman Noël (2011).

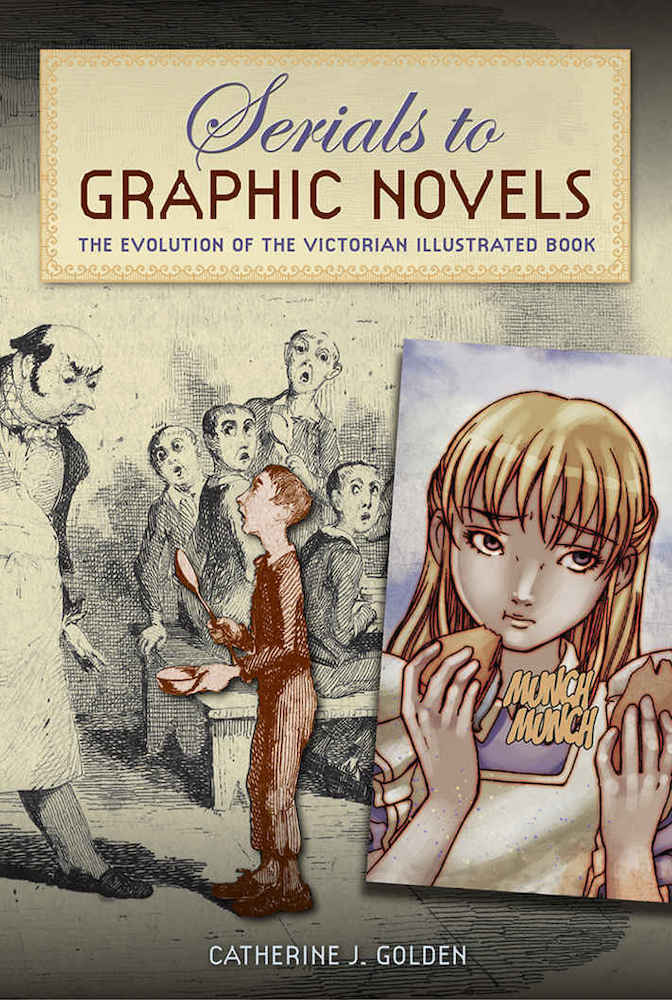

Golden tells a complex story with assurance, pausing whenever necessary to provide background and define her terms, as well as quoting from perceptive commentaries from illustration studies and from a larger body of biographical, bibliographical, art-historical, and theoretical criticism. In the process, she takes the reader on a Grand Tour from the beginnings of the British illustrated book with the tempestuous initial backstory of Pickwick, to its multitudinous and lively descendants — children's books such as Beatrix Potter's The Tale of Peter Rabbit (1902) and graphic novels of our own time such as Will Eisner's Fagin the Jew (2003, the second half of which reconfigures the storyline and characters of Oliver). Golden's cover, designed for our own visual age, features colourised versions of illustrations that represent this same chronological and artistic range, maiking palpable the connection between George Cruickshank's Oliver Asking for More in Bentley's Miscellany (February 1837) and Erica Awano's She Felt a Violent Blow on Her Chin from Leah Moore and John Reppion's The Complete Alice in Wonderland (2009; copyright 2014), anticipating the discussion of cartooning techniques and "classic" graphic novels in the concluding chapter.

Although she addresses a non-specialist audience, Golden has situated her discussion of nineteenth-century illustration within a framework of some of the standard texts on the subject, including a baker's dozen of authoritative discussions, from Forrest Reid's Illustrators of the Eighteen Sixties (1928), to Brian Maidment's Comedy, Caricature and the Social Order, 1820-50 (2013). As Simon Cooke has pointed out in his review of Golden's book, "Making sense of Victorian illustration is a complicated task," and Golden's makes this much more than a survey by arguing that the modern graphic novel is the lineal descendant of the Victorian illustrated novel. However, she simplifies her consideration of the nineteenth-century form itself by conveniently dividing the topic into the "pre-Victorian" or Regency grotesque satires of Gillray and Rowlandson; the witty caricatures of George Cruikshank and Phiz; the poetic realism and high craftsmanship of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, J. E. Millais, A. B. Houghton, and George Pinwell; the esoteric eroticism of Aubrey Beardsley; and the sophisticated magazine satires of fin de siecle illustrator George Du Maurier. Moreover, even as she surveys changes in the technology and marketing or packaging of nineteenth-century illustration, Golden offers cogent commentaries upon such specific plates as Robert Seymour's Mr. Pickwick in Chase of His Hat from the fourth chapter of The Pickwick Papers (May 1836), the novel that is the focus of her initial chapter.

Right: Seymour's "Mr Pickwick in chase of his hat."

Particularly useful, especially for the novice, is Golden's inclusion of high-resolution reproductions of the illustrations as she discusses them, as, for example, with the "pregnant moment" in this rarely reproduced Seymour illustration. "This is the pregnant moment Seymour stages," writes Golden:

Samuel Pickwick's respectable black hat, placed brim down in the cloud of dust, serves as an essential prop on Seymour's illustrative stage. Although hats are not commonplace today, to the Victorians, a misplaced hat in public was more than a major wardrobe malfunction: losing one's hat meant losing one's dignity. Seymour hints at the future restoration of the hat by showing a flustered Pickwick, extending both of his arms to "seize [the hat] by the crown, and stick firmly on your head: smiling pleasantly all the time, as if you thought it as good a joke as anybody else".... An onlooker gingerly sticks out his foot as if to stop the hat's approach before it is flattened by the oncoming open barouche; this choice of Regency vehicle affords the artist the opportunity to show mirth on the faces of all the passengers, who ... consider Mr. Pickwick's hat chase a very good joke indeed. Two jeering members of the crowd waive their own hats at Mr. Pickwick as if to magnify that they have what he has lost (but happily will soon regain). One onlooker even climbs high up a tree to get a better view of Pickwick's distressed spectacled face and his rounded butt. [27]

This leads on nicely into the main part of the book, as Golden identifies and explores the origins of the Victorian illustrated novel by examining in depth Dickens's nineteen-month serialisation of Pickwick, and in particular the pair of collaborative relationships that produced this seminal work.

Pickwick was not the first serialized novel, but Golden rightly identifies it as the one which shaped subsequent developments and became the "model for publication of newly released, illustrated serial fiction for adult readers" (49). In her first chapter she considers in depth the circumstances of the book's production, with several illustrators attempting to work with Dickens before he settled upon Phiz: the young writer and his original artist, Seymour, had jostled for position, each trying to decide whether it was a novel with pictures or a picture-book with words. Seymour had had a head start, because Chapman and Hall had originally commissioned him first, as an established and popular illustrator, and then recruited the twenty-four-year-old Dickens as a relatively unknown parliamentary reporter turned journalist, to furnish twenty-four pages of commentary each month. Although they contracted the young author of Sketches by Boz merely to "write up" Seymour's humorous pictures of Cockney sportsmen making fools of themselves, Boz quickly hijacked Seymour's project, making his text "the hand," and the illustrations "the glove" rather than vice-versa as Seymour had expected. All this is teased out at length as Golden links the novel's evolution with the other, cultural factors which helped to determine its form, among them the rise of "Victorian commodity culture, new printing technologies, growth of the middle class ... a climbing literacy rate, and increase in the population [and] the growth of leisure time" (312). Golden excels at summarising key threads, and here, as elsewhere, she re-casts the Victorian serial (whether in detached monthly parts or within weekly and monthly magazines) as an intersection of cultural ideas, values, and forms.

The subsequent commercial success of the serialised novel owed much to this part-published picaresque story: it set the nineteenth-century standard and became the "model for publication of newly released, illustrated serial fiction for adult readers" (49). As Golden says,

Dickens quickly elevated the authority of the author over the artist and essentially reversed the dynamic for future author and artist collaborations: to recall [Pierce] Egan's own analogy of the relationship between author and artist, Dickens turned the illustrator into a "glove," molded to fit the author's "hand." Increasing the allotment of text [to thirty-two pages per instalment] and decreasing the number of plates [under Buss, and then Phiz, to just two] expanded the author's role, granting Dickens greater room for plot and character development. With this improved plan, Dickens earned more money (21 a part); however, by cutting the number of plates in half and hiring artists less established than Robert Seymour, Chapman and Hall offset the total cost. [29]

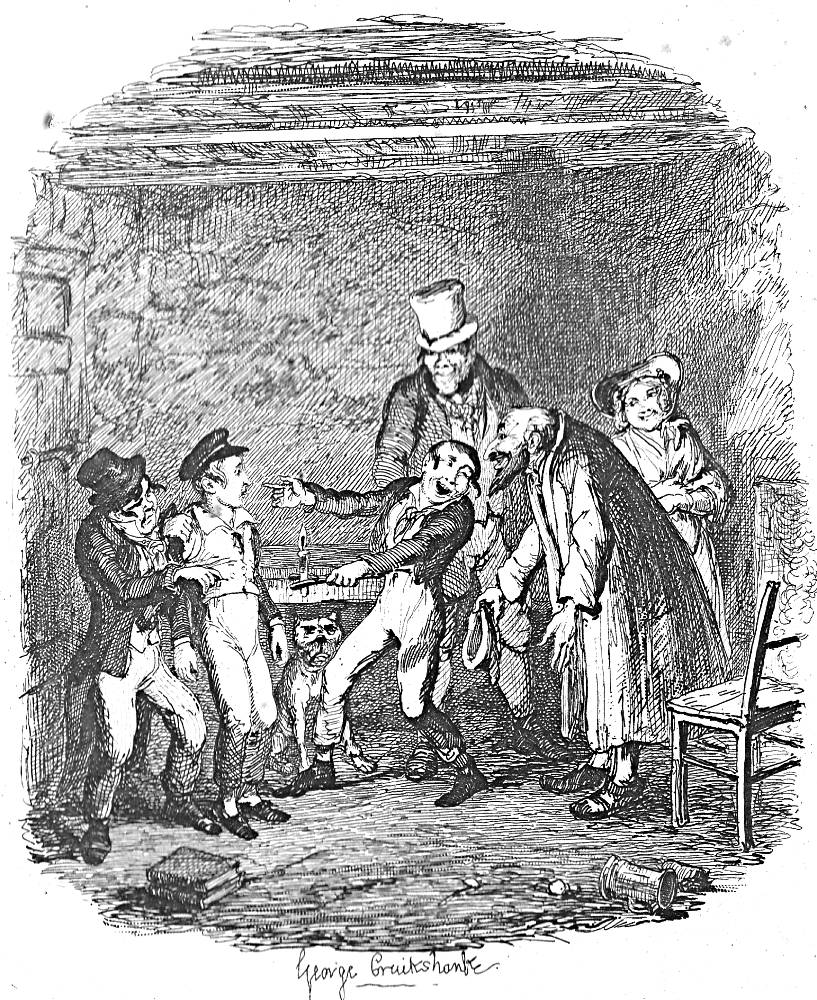

In the second chapter, Golden moves on to read serial illustration against the conventions of melodrama. She defines and re-reads caricature as a kind of distortion, akin to satire, and considers it in terms of its stage-craft. Her manner of interpreting caricatural illustration incorporates stage effects of lighting and visual cuing (58), gestures and props (66), and "bodily distortion" (77). Thus, she sheds light on the methodology of the caricaturist, for example, showing how Cruikshank employed tableaux vivant in his etchings for Dickens's magazine serial Oliver Twist (1838). "Golden charts the ways in which they capture the immediacy of the theatre, involving the reader-viewer in a visceral experience between laughter and horror. She also concedes the limitations of caricature as a mode of illustration and the rise of a more realistic approach" (Cooke).

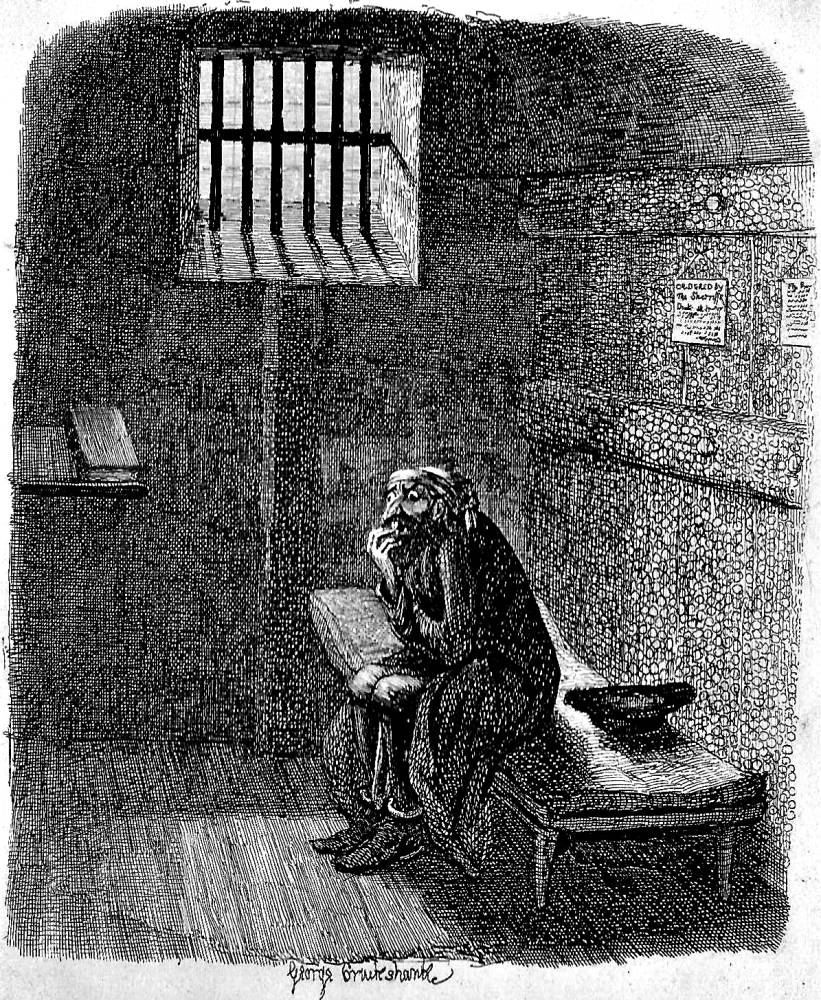

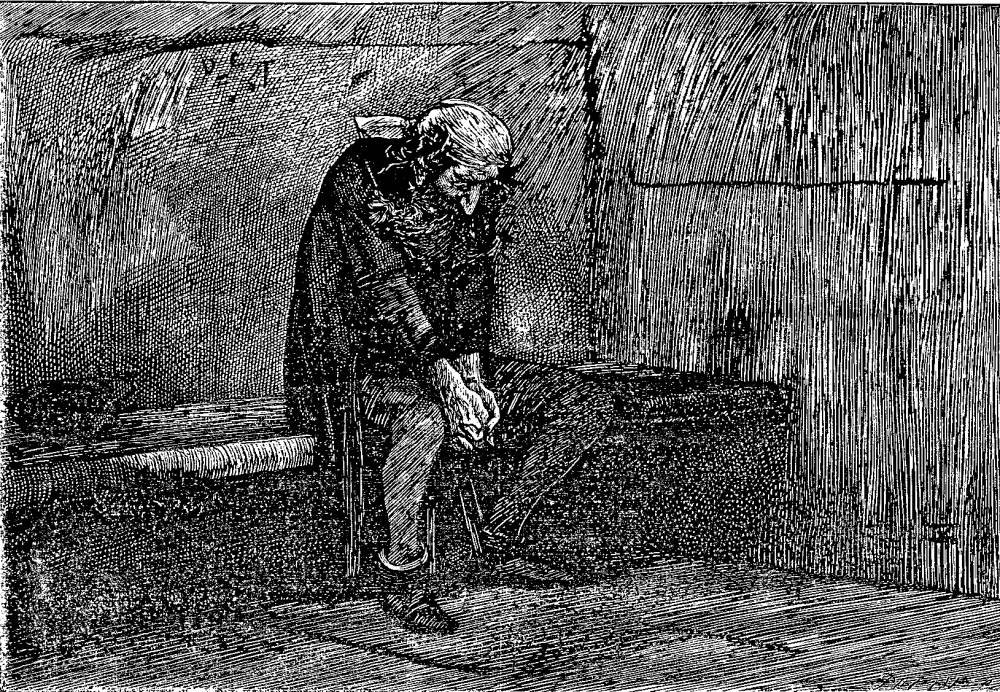

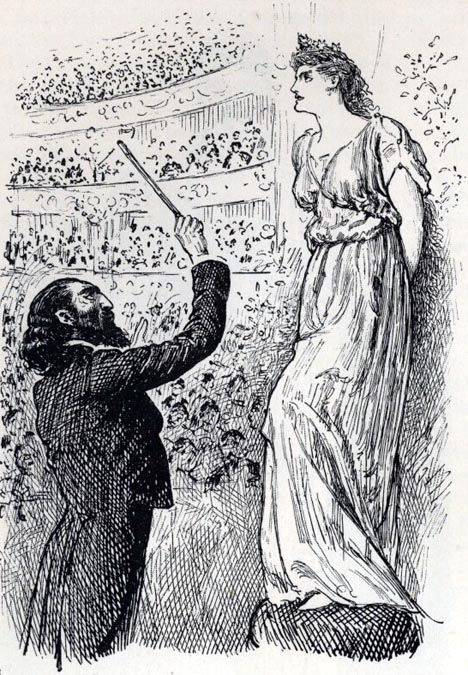

Three anti-Semitic images, 1839 to 1894, suggesting visual continuity. Left to right: (a) Cruikshank's Fagin in the Condemned Cell. (b) James Mahoney's treatment of the same scene (1873). (c) Du Maurier's Svengali in The 'Rosamund' of Schubert (January 1894).

This change in popular taste occurred in the 1850s as the artists of the Sixties supplanted the practically rather than academically trained Phiz and Cruikshank. However, Golden notes that the caricatural conventions of the illustrated serial existed alongside the naturalism of the New Men of the Sixties in the illustrations of artists such as Millais and Du Maurier. Golden makes the linkages between these academically trained illustrators and the previous generation of story-telling caricaturists explicit in her discussion of later Dickensian illustration, particularly in the Household Edition, which was based on and constantly adverted to the visual narratives of Cruikshank and Phiz. Comparisons between the earlier and later treatments of scenes such as Fagin in the Condemned Cell — the original by Cruikshank (1838) and the later rendition by James Mahoney in the Household Edition of 1873, as shown above, with another later illustration by Du Maurier, clearly display the visual continuity as the old serial conventions were assimilated into the works of the realists.

In Chapter Three, Golden moves from a brief discussion of Dante Gabriel Rosetti's fine art Pre-Raphaelite illustrations for William Allingham's Maids of Elfen-Mere (1855) illustration to Lewis Carroll's original, amateurish sketches and Tenniel's professionally revised Alice illustrations to demonstrate how caricatural elements continued after the Sixties to inform the new realism.

Ironically, in opening her fourth chapter, "Fin-de-Sicle Developments of the Victorian Illustrated Book," which concerns the final stage of nineteenth-century British book illustration, Golden demonstrates through the Du Maurier remark about Phiz (quoted at the top of this review) the enduring popularity of the artists in the first stage. And, indeed, the powerful legacy of the caricaturists Phiz, Leech, and Cruikshank is a theme to which Golden continually reverts, privileging those small-scale, steel engravings of the 1830s — sometimes humorous, sometimes melodramatic — through the 1850s over the large-scale naturalistic composite wood engravings of the New Men of the Sixties. A significant part of Golden's critical re-assessment involves defining the relationship between the two styles.

Sixties realism, with its larger scale, high finish, photographic three-dimensionalism, and academic style was certainly in vogue. "By the mid-nineteenth century," she explains, "the public desired artistic book illustration with the lifelike quality of photography" — partly inspired by the Great Exhibition of 1851, with its "richly illustrated exhibition catalogue in a representational style (also referred to as realism or naturalism)" (9-10). Significantly, Dickens himself abandoned Phiz after dissatisfaction with the old-fashioned look of Browne's short program for A Tale of Two Cities in November 1859 and turned to New Men of the Sixties such as Marcus Stone. The Victorian illustrated book, itself, waned as a vehicle for newly released wide-circulation publication in volume form (151). Golden cites such "intertwining economic and aesthetic factors" as the decline in the production of serial fiction that occurred as prosperity and literacy became more general. She notes, too, "the changing nature of the novel, new developments in illustration, and competition from other media" (152), not only photography, but, later, cinema. Then, too, one should consider the impact of literacy legislation during the last third of the century:

. . . a comparison of literacy figures from the first nationwide census published in 1840 — a time when the illustrated book enjoyed enormous popularity — to the census figures of 1900 — when newly released wide-circulation Victorian illustrated adult fiction was waning in England — reveals a marked increase in literacy, The 1840 census (based on data up until 20 June 1839) lists 67 percent of males and 51 per cent of females as literate. By 1900 — thirty years after the passage of the Forster Act of 1870 (legislation that made education compulsory in England and Wales for children between the ages of five ad thirteen) — 97.2 percent of males ad 96.8 percent of females in England and Wales were literate. [153]

In particular, Golden explains, the development of the subscription library (Mudie's and W. H. Smith) led to increased demand for the triple-decker so that multiple readers could borrow and be reading the same title at one time. For example, "By 1890, Mudie's Select Library (1725-1960) had 250,000 subscribers" (152). The phenomenon of the public library accelerated this shift in production of literary texts towards the triple-decker. The Public Libraries Act of 1850 granted local boroughs with populations over 10,000 the right to open to lending libraries. It allowed local authorities to impose a local tax of one penny to pay for the service, and thereby enshrined the new public service. At the inauguration of the first such public institution, the Manchester Free Library (with an initial collection of 18,000 books), Dickens spoke on 2 September 1852. Dickens himself, however, did not immediately shift to the new library-friendly triple-decker format, and continued to publish in serial right up to his death in 1870, although from Great Expectations (1861) onward he shifted to triple-decker volume publication, partly from the demands of libraries, major purchasers of new fiction, and partly from new economies in publishing. The ideal form of illustration was now the composite woodblock engraving, which could be produced on the same press as the text of the novel.

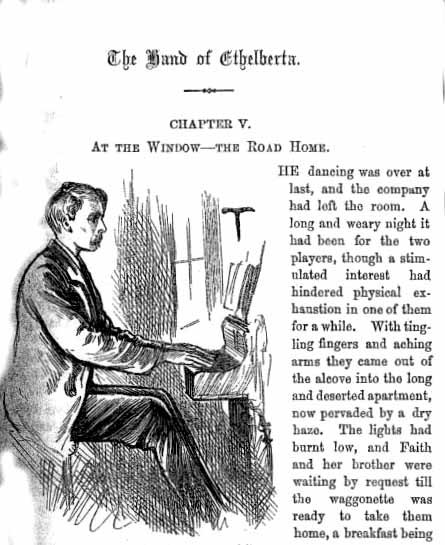

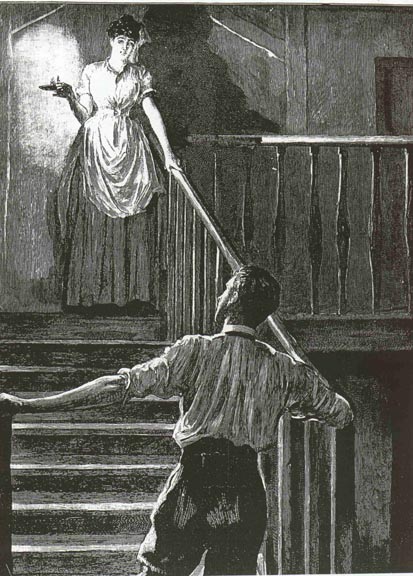

Left to right: (a) Robert Barnes's large-scale illustration for the Graphic, Farfrae was footing a quaint little dance with Elizabeth Jane for Thomas Hardy's Mayor of Casterbridge, 13 February 1886. (b) George Du Maurier's Decorative Initial "I", designed for Thomas Hardy's The Hand of Ethelberta serialised in The Cornhill 32 (August 1875): 233. (c) Daniel Wehrschmidt's large-scale illustration Clare came down from the landing above in his shirt-sleeves, and put his arms across the stair-way for Thomas Hardy's Tess of the D'Urbervilles serialised in The Graphic Part 12 (26 September 1891): 358.

In fact, there seem to have been two distinct markets for fiction in the last two decades of the century in England and Wales. Whereas readers of periodicals such as The Graphic, The Illustrated London News, and The Cornhill read the serialised works of novelists such as Thomas Hardy with composite woodblock illustrations, purchasers of the equivalent volume editions of previously serialised novels such as The Mayor of Casterbridge (1886), illustrated by Robert Barnes, and The and of Ethelberta (1875-76), illustrated by George Du Maurier, read unadorned texts that included, at best, a frontispiece and Hardy's map of Wessex. Golden's conclusion is that "Hardy's fiction published in volume form without the original illustrations came to be considered his serious literary work" (153).

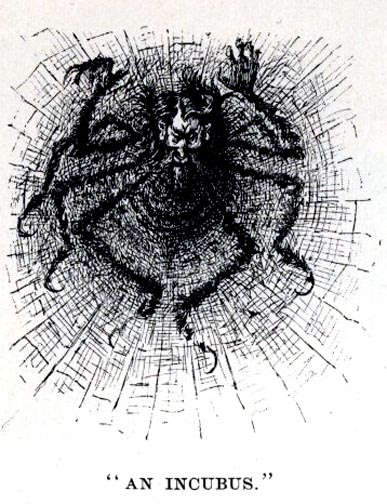

Three more anti-Semitic Images, 1838-94: (a) Cruikshank's etching Oliver's reception by Fagin and the Boys for Oliver Twist in Bentley's Miscellany, November 1837; (b) Du Maurier's whimsical and horrific An Incubus for Trilby in Harper's New Monthly Magazine, 88 (March 1894): 576. (c) One of Du Maurier's realistic portraits of Svengali, Au clair de la lune for Trilby in Harper's New Monthly Magazine, 89 (June 1894): 78.

At the Fin de Siecle, the Victorian illustrated book entered its third iteration as professionally trained artists such as George Du Maurier in works such as Trilby (1894) achieved a fusion of realism and caricature, both in serial and volume forms. Golden shows through graphic examples how, in depicting the evil genius of Svengali as a stereotypical Jew, Du Maurier drew upon Cruikshank's depictions of Dickens's Fagin, and thereby integrates examples of anti-Semitism from across the century. The most telling piece of evidence that the caricatural form survived to the end of the century is Du Maurier's characterisation of the patiently plotting, devious, and manipulative Svegali in the centre of a web of his own creation, an emblem of his succeeding in controlling Trilby O'Farrell as the operatic diva La Svengali:

In making Svengali a Jew and a devil, Du Maurier is reengaging a racialized depiction of the Jew prominent in Oliver Twist. Cruikshank's depiction recalls the medieval conception of the wandering Jew; excluded from Christian nation-state, that also appears in cartoons by Isaac Cruikshank and Thomas Rowlandson. [Rosenberg, Kerker, and Bristow have examined]... the villainous Jew — a type that extends from Shakespeare's Jewish moneylender in The Merchant of Venice to Dickens's "receiver of stolen goods" OT, ... xxv).... Moreover, as critics have often noted, Dickens and Cruikshank's Fagin prescribes to conventions of the archetypal "stage Jew," noted not only for strangeness and ugliness, but also deceitfulness, demonism, smarminess, and greed, qualities that reappear in Svengali's characterization. [179-80]

In the scene in "The Three Cripples," Cruikshank had emphasized the length of Fagin's nose by contrasting it with the snub-nose of criminal-wannabe "Morris Bolter" (Noah Claypole's London nom de guerre), and in his depictions of the novel's villain Du Maurier likewise exaggerates Svengali's nose: "it is long enough to signal in Fagin-like fashion that he, too, is in the know of Jewish villainy" (182), although Du Maurier emphasizes the wildness of his villain's hair ("here fashioned to suggest a devil's horns") rather than the length of his nose in An Incubus (March 1894). This species of dark comedy that embodies Trilby's fears as it both spoofs and dehumanizes the antagonist: "he is part human, part arachnid, and part demon" (183). Here Du Maurier is clearly working within the conventions of the caricatural school to convey a psychological reification of the heroine's terror.

The successes of the illustrated novels of George Du Maurier in the last decade of the nineteenth century run counter to a sharp decline in illustrated, volume-length, adult-oriented fiction. Increased literacy rates and middle-class prejudice against pictures in books intended for adult consumption led to a marked decrease in newly released illustrated adult fiction. However, illustrated adult fiction continued to flourish in magazines, artists' books, and children's literature such as the Peter Rabbit books of Beatrix Potter (1902). Following in the footsteps of Millais, in such pieces as The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin (1903) she combined naturalistic, near-photographic realism with the animal tale then much in vogue, and exemplified by such works as A. A. Milne's Winnie-the-Pooh (1926) and Kenneth Grahame's The Wind in the Willows (1908). Other artists of the period who combined such elements in children's books include Edward Lear, Arthur Rackham, E. W. Kemble, Randolph Caldecott, Walter Crane, and Kate Greenaway. Victorian illustration did not vanish; rather, argues Golden, it evolved as it was absorbed into both children's books and works of poetry such as Christina Rosseti's Goblin Market (1862).

In her fifth and final chapter, "The Victorian Graphic Classics — Heir of the Victorian Illustrated Book," Golden completes her argument that "the graphic classic is reviving a genre that a century before recognized pictures play a central role in the development of plot and characterization" (11). She contends that the graphic novel is the lineal descendant of the Victorian illustrated novel. That she chooses canonical adaptations of such classics as Oliver Twist and Alice constitutes highly selective evidence. However, her examination of the dynamics of the cartoon-strip panel demonstrates how modern illustrators have been able to move beyond the "pregnant moment" of the early caricaturists to convey motion as well as static image. She usefully "surveys graphic novel adaptations of nineteenth-century novels by Jane Austen, Charlotte and Emily Brontë, Dickens, and Anthony Trollope as well as Neo-Victorian graphic novels (for example, The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen [1999]) and original Victorian-themed graphic novels (for example, Batman Noël [2011]) (11).

On the concluding page, Golden sums up how the script writers and artists of "graphic classics" have adapted such nineteenth-century illustrated works as Alice and Oliver by using the medium of the cartoon strip to communicate meaning and achieve emphasis:

panels of different shapes and sizes, and new approaches to iconic illustrations demonstrate the graphic novel's ability to re-shape a nineteenth-century classic into form that engages twenty-first century readers with words and images on multiple levels. The graphic classics refashions [sic] the style and creative vision of an author or illustrator into prescient hybrid form that recalls the revelatory dimension of the Victorian definition of illustration and resituates the nineteenth-century novel for a new age. Peeling back these layers of illustration reveals the still powerful original imprint of the Victorian caricaturist and realist. [234]

This assessment of the style of the graphic novel implies a comfortable co-existence of letterpress and image, but the form of the cartoon panel insists upon the primacy of the image over the word, as if the picture is now the hand, and the words of the author (usually amounting to dialogue in a dramatic freeze-frame) are once again the glove. This twenty-first century fusion of the word and the image privileges the latter over the former, just as Seymour and Cruikshank would have wished. Thus, in bringing us up to date on the trajectory of the Victorian illustrated book, Golden seems to have brought us full circle.

Through discussing specific graphic adaptations of such nineteenth-century works as Alice, Golden has demonstrated the ways in which the Victorian illustrated book has proven a highly resilient genre, one that has found "new expression for our time" (233) by exploring present-day issues that would have been taboo to the Victorian readership. It has done so in a format that innovatively uses language as image, and entirely dispenses with conventional narrative techniques. "The graphic classics returns to, reuses, modifies, and some cases remediates characters and iconic scenes and also foregrounds historical and psychological elements indelicate for a Victorian readership" (233-34).

To return to the front cover: the juxtaposed images here, of a colourized version of George Cruikshank's iconic engraving of February 1837, Oliver's asking for more, and a twenty-first century frame from a graphic novel, Erica Awano's 2009 colour plate of Alice munching on the magic cake, signifies the close affiliations between the illustrators and illustrations of the Victorian age and those of graphic classics in our own time, "before," as Simon Cooke concludes, "we have even opened the book." Particularly compelling are Golden's detailed analyses of specific panels in "adapted" classics, especially Austen's Pride and Prejudice and Dickens's A Christmas Carol (which re-tells the conversion of an inveterate miser by substituting Batman for Ebenezer Scrooge). Golden's treatment of the legion of illustrators who constitute the New Men of the Sixties, including such notable female artists as Hardy illustrator Helen Paterson Allingham, is rather light. But in one relatively compact book (268 pages of text and notes plus thirty pages of bibliography and index) she offers a scrupulously researched, carefully argued, and amply illustrated discussion of her subject, with insightful analyses of individual illustrations, which are effectively reproduced, and are often adjacent to their critical discussions. Her concluding point, that the 2012 adaptors of Oliver Twist have been able to re-shape the relationship between Bill Sikes and Nancy as a visual commentary on battered woman syndrome, forcefully demonstrates that the graphic novel revisits classics not merely to entertain young readers or bring their stories and characters up-to-date, but to address the important social issues of the twenty-first century.

Works Cited

Cooke, Simon. "A Review of Catherine Goldens Serials to Graphic Novels: The Evolution of the Victorian Illustrated Book. The Victorian Web. 6 February 2018.

Golden, Catherine J. Serials to Graphic Novels: The Evolution of the Victorian Illustrated Book. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2017; in paperback, 2019. 320pp. ISBN: 978-0813064987. 25.95; $24.95 USD.

Created 14 October 2019