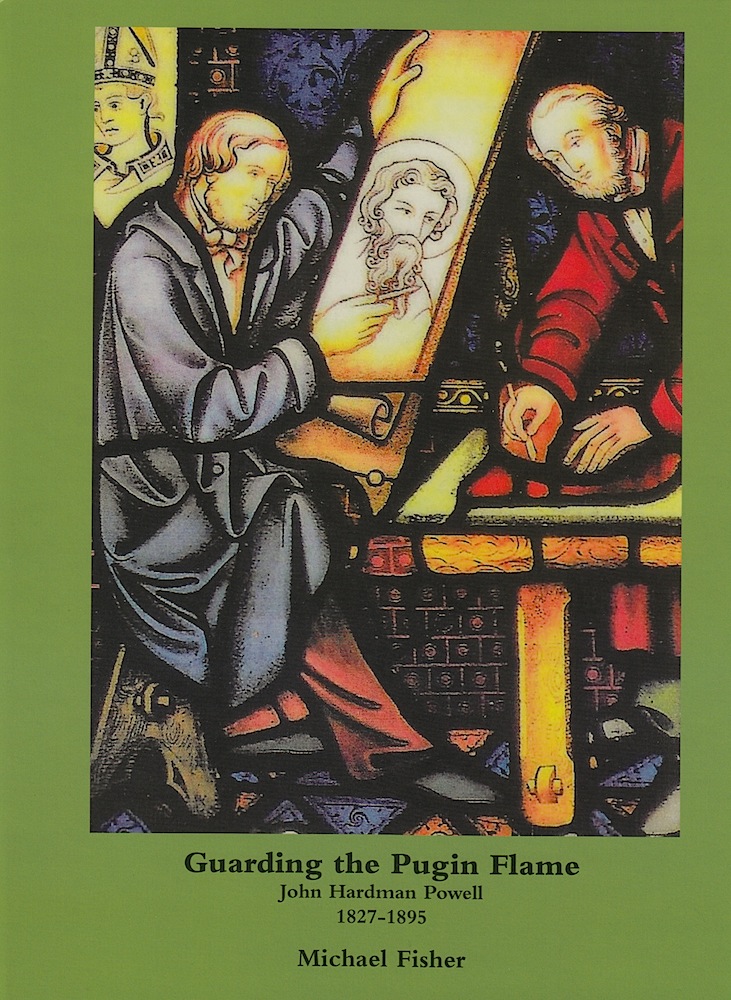

Apart from the scan of the front cover, and the plate showing the Medieval Court at the Great Exhibition (source given in bibliography), the illustrations here come from our own website. Click on them for larger pictures and more information.

In this detail of the Glassworkers' Window in St Chad's Cathedral, Birmingham, Hardmans' artisans are hard at work in the studio.

When we think of the Gothic Revival and the Arts and Crafts Movement of the later part of the Victorian period, the names that come to mind are those of A. W. N. Pugin, John Ruskin and William Morris. But Michael Fisher has another "trinity" for us: Pugin, John Hardman (of the Birmingham metalwork and stained-glass firm), and Hardman's nephew, John Hardman Powell. Together, he says, these three "transformed the architectural and artistic tastes of Victorian England" (13). The quotation in the book's title derives from Powell's own description of himself as the "guardian of the Pugin flame" (qtd. p. 191), and, as the next words indicate, Powell himself is the main focus here. He was Pugin's only pupil and later his son-in-law. He would eventually become the chief designer of Hardmans, carrying Pugin's inspiration through almost to the end of the nineteenth century. Fisher sets out to reveal Powell's personality and influence, exploring his training with Pugin, his involvement with the Pugins as a family, and his importance in his own right as a designer in a variety of media.

The Ramsgate Years

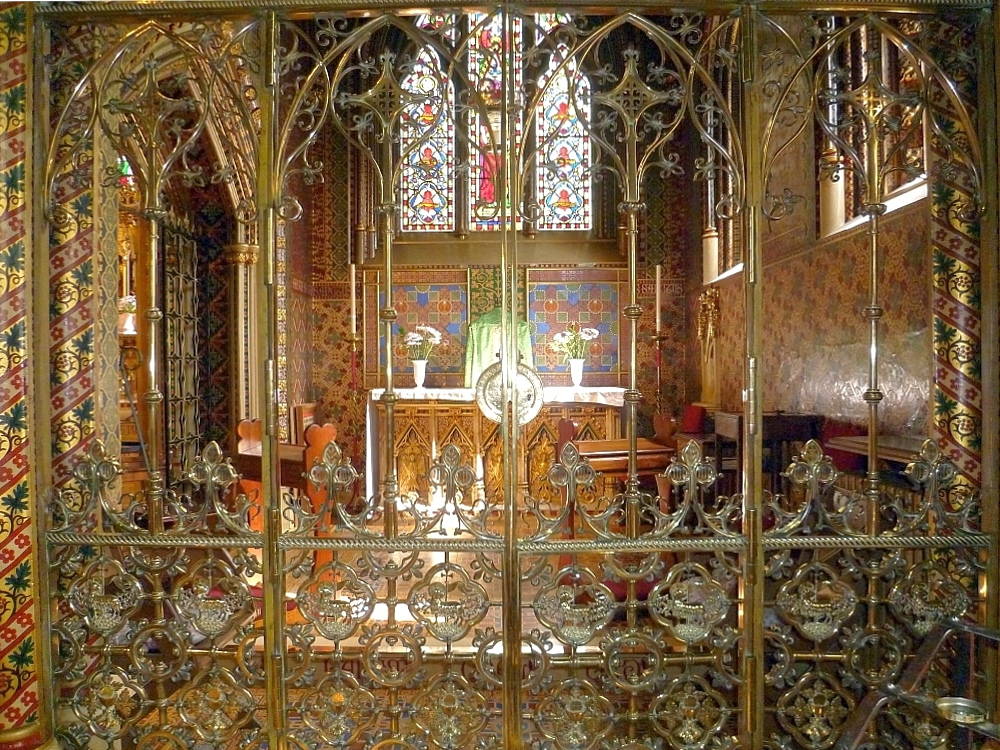

Left: The rood screen at St Giles, Cheadle. Right: The screen in front of the Blessed Sacrament Chapel there.

The first chapter, entitled "The Magician's Apprentice," is headed by another brief quotation from Powell — "Pugin ... poured out fifteenth-century drawings like a conjuror." Powell's notes of 1865, intended to preface "Photographs from Sketches by A. W. N. Pugin," show how struck the young man was by his new master's creative energy. Only seventeen when he came to join the family at The Grange in Ramsgate, he faced a tough initiation into his new life. Crushing his toe on the first night, when trying to assemble his brass bed, was the least of it. He quickly had to adjust to Pugin's quirks, and the white heat at which he operated. Specifically, he had to unlearn most of what he had previously learned at Elkingtons, the art metalworkers in Birmingham, because it was incompatible with "The Real Thing" — Gothic. Luckily, he proved an apt pupil, and the qualities that Pugin had noticed in him earlier on, during his dealings with his uncle, blossomed under this new regime. Powell was soon involved with metalwork designs for St Giles, Cheadle, and the House of Lords. Once Pugin was able to persuade Hardman to execute his stained glass for him, there was cartooning as well. Although Powell's apprenticeship ended in 1848, he was quickly coaxed back from Birmingham again under a new arrangement, and continued to assist in the "Governor's" many projects. His subsequent marriage to Pugin's daughter Anne in 1850 involved him even more closely in the family.

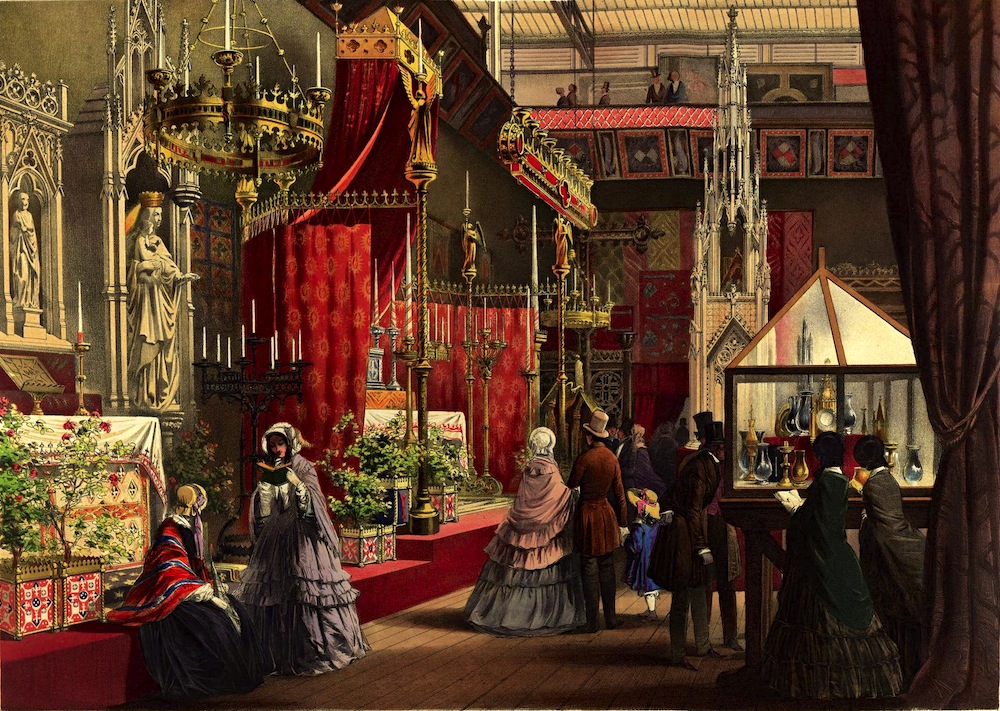

The Medieval Court, arranged by Pugin. Powell contributed the designs for Hardmans' ecclesiastical metalwork. Illustration by Louis Hague. Source: Nash, Vol II, XII.

Projects on the scale of the Medieval Court at Great Exhibition of 1851, shown above, were highly stressful. Both Pugin and Powell were overworked, their health suffered, and their young families gave them anxiety as well as joy. "Incessant powerful screeching, prolonged Screams. oh dear — to design gas fittings in this," wrote Pugin to Hardman on 4 September 1851 (qtd. p. 44). To both men's dismay, Anne Powell took a long time to recover from the birth of her first child, and was hardly over it before the breakdown that led to her father's premature death.

The Birmingham Years

Chapter 2, "In the wake of Pugin, 1852 - c.1861," shows Powell taking on a great deal of responsibility for the bereaved family: The Grange was let, his own house in Ramsgate packed up, and both families moved up to Birmingham. Pugin's eldest son, Edward, a mere teenager, spend the next couple of years there too, with Powell and his uncle doing all they could to support the bereaved family and assist in the completion of Pugin's unfinished projects, as well as providing designs in various media, including needlework (see p. 98). No one knows more than Fisher about life in the Midlands, and specifically Catholic life, so the detail here is fascinating. He also shows how both Edward Pugin and Powell started to develop more individual styles, with the former turning more towards French Gothic, and the figures in the latter's stained-glass windows becoming more fluid, "dramatic and expressive, full of life and movement" (58), with pastel shades being added to the palette. The cover picture, reproduced again here, is a good example of Powell's work in this transitional period.

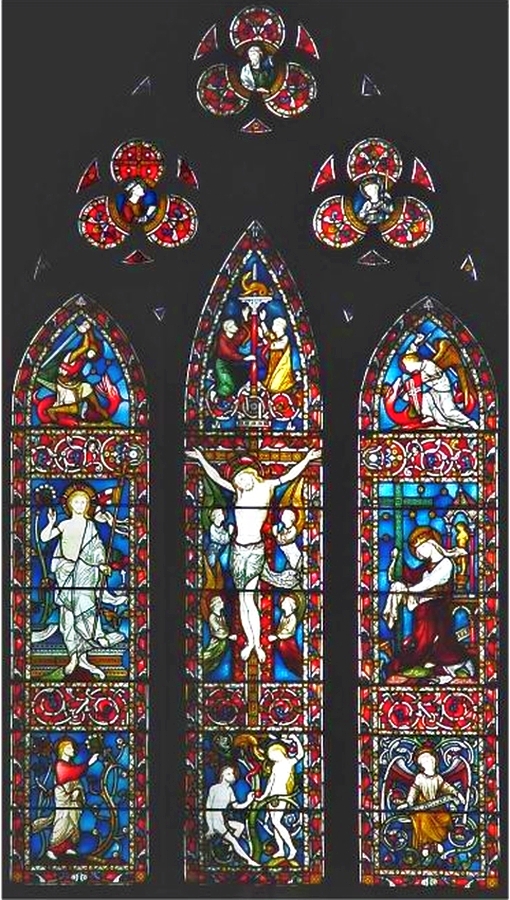

Examples of windows installed in the 1870s and 1880s, left to right: (a) The Spode Memorial Window, Lichfield Cathedral (1870). (b) The Natvity and the Adoration of the Magi in St Matthias, Richmond (1876). (c) Close-up of St Matthew and St Luke in St Matthew's, Ashford, Surrey (1880).

Business boomed in Birmingham. Major projects included the great complex east window of Worcester Cathedral, and the International Exhibition of 1862. Fisher is able to give us some information about the master-craftsmen who had come up with Powell from Ramsgate, like the gilder and decorator Thomas Earley (1819-1893), who had played a major role in presenting the Medieval Court of 1851. But large numbers of new employees were now being taken in, and Hardman began passing on his knowledge to them. He started assembling notes and giving lectures not only in the studio, but also in the Birmingham Institute. This way of "guarding the flame" would no doubt have met with Pugin's wholehearted approval — especially since Hardman "imparted not just the skills, but the whole rationale of Gothic art, and its roots in the Catholic Faith in which Powell had been nurtured" (117). As for the younger Pugin, he spread his wings too, expanding his own architectural practice, and moving first to London and then back to Ramsgate. But this did not save Powell from having to deal with him. The "storm approaching" in the title of the next chapter refers to Edward's suspicion that, with Hardmans continuing to fulfil commissions from the Palace of Westminster, the family had not been properly recompensed for his father's designs. Fizzing with energy like his father and also litigious, Edward Pugin would continue to cause trouble for Powell — who, for his part, showed great forbearance and continued to do his best for the family as a whole. Despite the playful sense of humour evident in many of his sketches, Powell was subject to low moods, and this was sometimes a hard burden to bear. Fisher's access to hitherto unpublished material pays dividends here.

Changing Places

Among the important events of the last two chapters are Powell's seven-week tour of Italy with Stuart Knill, a cousin of Pugin's third wife Jane, and his own close friend. Fisher surmises that this was not only to reinvigorate Powell, but to retrace the steps of Pugin's tour of 1847. The two men were to see the architecture that had inspired the "master," and, like him, to have an audience with the Pope. Nothing could better demonstrate Pugin's lasting influence. Not long afterwards, there was to be a more momentous event. Such was the volume of work now that it was necessary to divide the Birmingham firm's operations into two: the glassworks and memorial brasses remained at one site as John Hardman & Co., while metalwork went to a new site, under the name of Hardman, Powell & Co. The Powell here was John's brother William, because John Hardman Powell himself moved south again, this time to Blackheath on the outskirts of London, so that he could manage the London office. He was to die here on 2 March 1892, in an influenza epidemic, just before his sixty-eighth birthday. It says much about their upbringing that three of the Powells' daughters became nuns. Two of the Powells' other girls married (one to Stuart Knill's son, John), but none of the boys, so their branch of the family ended with them. But, as Fisher says, Powell's inspiration lived on, and through that, Pugin's too for many years. For example, Hardmans' restoration of the Palace of Westminster's stained glass continued until 1955, and the company was only finally wound up in 2009.

Looking Back

Pugin's second wife, Louisa, and three of his children, in one of the chapel windows at The Grange.

Guarding the Pugin Flame is a fine contribution to the burgeoning field of Pugin studies. The most notable contributors so far have been the late Margaret Belcher, whose 1987 critical bibliography was followed by her five indispensable volumes of Pugin's letters (2001-15); Rosemary Hill, who popularised "God's Architect" with her first-rate biography of him in 2007; Stanley Shepherd, with his invaluable companion to Pugin's stained glass (2009); Roderick O'Donnell, with his The Pugins and the Catholic Midlands (2002); and Fisher himself, whose "Gothic For Ever": A. W. N. Pugin, Lord Shrewsbury, and the Rebuilding of Catholic England was published in 2012. Our view of Powell's "Master" has been rounded out from other angles as well, by Patricia Spencer-Silver's book on George Meyers, Pugin's Builder, which appeared as early as 1993, and Catriona Blaker's book on Pugin's eldest son Edward (Edward Pugin and Kent, which came out in 2012. Several of these have already been reviewed in the Victorian Web (see "Related Material" at the end). More recently, Caroline Shenton's Mr Barry's War deals with the collaboration of the two architects on the Palace of Westminster, acknowledging Barry's "fatal error of judgement and uncharacteristic lack of generosity" in failing to give due credit to Pugin (174). As Fisher points out, Powell himself described the nature of the two architects' collaboration perfectly: "Sir Charles Barry might justly be compared to a parallelogram, Augustus Welby Pugin to a spire; the work might be represented as a cube out of which a subject was to be carved, and Pugin carved it..." (qtd. p. 163). But at the time of the opening of the House of Lords, when the matter might have come to the surface and been thrashed out, Pugin was in Italy, already trying to avert the threat of breakdown.

What is truly remarkable is how all these accounts reinforce the same picture of Pugin himself as a larger-than-life but precariously balanced personality — enormously gifted, enthusiastic and inspiring, yet at the same time volatile and driven. He himself was as generous with his praise as with his criticisms (often to, or of, the same person), outspoken, and no doubt frequently exasperating to deal with. He had no "side" and no sides, and was always himself, and those who were close to him loved him for that. It may not have been Fisher's primary aim, but it is one of the joys of his new book that it brings Pugin so unforgettably to life again through Powell's eyes, and indeed through the younger man's whole life's work.

There are one or two slips. For example, "drawings" in that quotation heading the first chapter should be "details" (see Belcher 149); and Margaret Belcher's critical bibliography appears in Fisher's own list of printed sources as a critical biography. We are happy to have provided the close-up of the Flanagan memorial window in St Chad's (fig. 3.22, p. 130), but would have been happier if it had been attributed to our photographer, Colin Price, and not just to our website. But these are minor points, worth mentioning only in case there is a later edition. There might well be: Guarding the Pugin Flame is handsomely illustrated throughout, often with Powell's drawings and works, and is heart-warming as well as richly informative. As regards the loyal, kindly, talented and hard-working Powell himself, it proves that Pugin was right when he said in the Tablet of 9 March 1851, in his typically buoyant way, "God will yet raise up some glorious men, who will restore his sanctuary, and obtain a great and final triumph for Christian art" (qtd. p. 227).

Related Material

- John Hardman & Co., An Introduction

- Review of Rosemary Hill's God's Architect: Pugin and the Building of Romantic Britain

- Review of Michael Fisher's "Gothic Forever": A. W. N. Pugin, Lord Shrewsbury, and the Rebuilding of Catholic England

- Review of Catriona Blaker's Edward Pugin and Kent: His Life and Work within the County

- A Brief Biography of Pugin

- Biography and Critical Introduction (Chapter on Pugin from Eastlake's History of the Gothic Revival, 1872)

References

Belcher, Margaret. A. W. N. Pugin: An Annotated Critical Bibliography. London: Mansell, 1987.

[Book under review] Fisher, Michael. Guarding the Pugin Flame: John Hardman Powell, 1827-1895. Downtown, Salisbury: Spire Books, 2017. 290 pp., with numerous illustrations. Hardback. £55.00. ISBN 978-1-904965-51-0.

[Illustration source] Nash, Joseph, et al. Dickinsons' Comprehensive Pictures of the Great Exhibition of 1851. London: Dickinson Brothers, 1852. Internet Archive, contributed by the Smithsonian Institution Libraries. Web. 20 March 2017.

Shenton, Caroline. Mr Barry's War: Rebuilding the Houses of Parliament after the Great Fire of 1834. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Last modified 21 March 2017