Photographs, apart from the first two historic ones, by the author. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one. Click on all the pictures for larger images.]

Lichfield Cathedral, Staffordshire (to give it its fuller name, Cathedral Church of the Blessed Virgin Mary and St Chad, Lichfield). Photochemical print dated 1890 from the Library of Congress digital collection, reproduction number LC-DIG-ppmsc-08545, with thanks.

The history of the cathedral goes right back to the beginning of the eighth century, but the building as it stands today owes much to its restoration by George Gilbert Scott (1811-1878). James Wyatt worked on it from 1788-95, and Sydney Smirke from 1842-46, but, says Nikolaus Pevsner, "in all stylistic considerations at Lichfield it must be remembered that the vast majority of the details is Scott's" (177). Scott took charge in 1857, and work continued after his death under his son, John Oldrid Scott (1841-1913). In this way, the Victorian restoration programme lasted right up until the end of the reign. The cathedral is of warmly modulated ashlar with slate roofs, and is relatively small, at only 371' long (Pevsner 174), but it is a pleasant walk from the main part of the picturesque town, and makes an extra impact because of its exceptionally beautiful natural setting, and the well-preserved Close around it. The cathedral is seen here across Minster Pool, in about 1890.

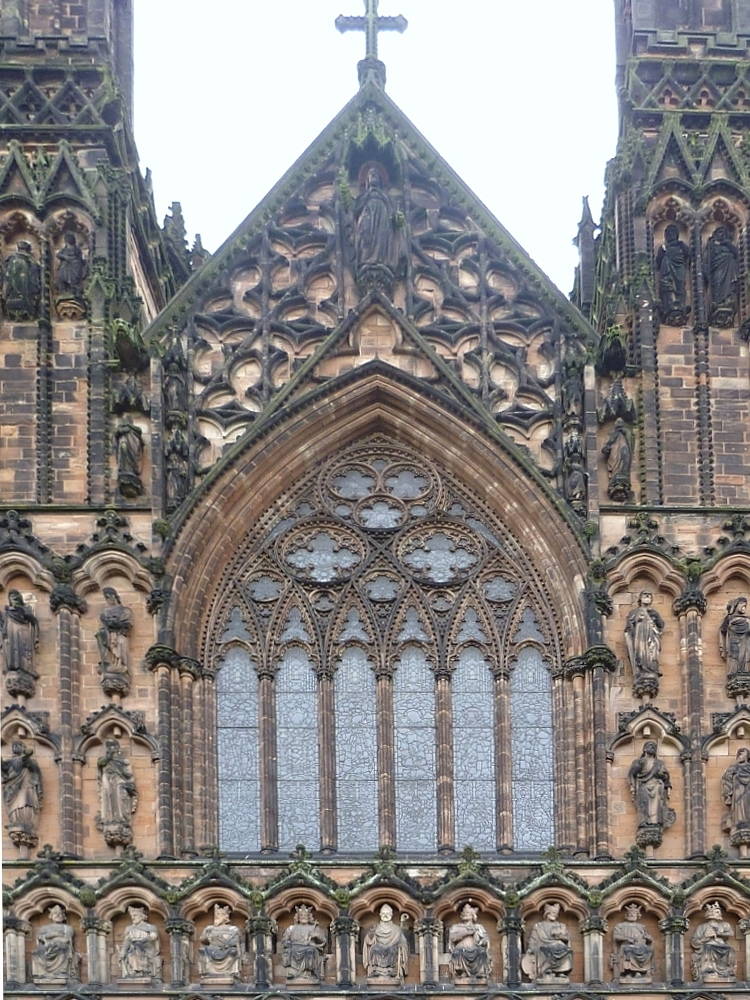

Left to right: (a) The Cathedral's west front in c.1898 (frontispiece to Clifton; see bibliography) . (b) Detail of façade, showing west window. (c) Main west entrance.

Looking at the exterior, Pevsner identifies "not only mouldings, capitals and statues, but also most of the window tracery" (177) as Scott's. He adds that he is unable to discover how accurately all this replaced what was already there. However, it is clear from Scott's severe criticisms of Wyatt's "tamperings" (Recollections, 296) that his own policy was to preserve as much as he could, and work sensitively around it.

As for the west front itself, Scott kept the worn but precious medieval relief of Christ in Majesty, blessing people, in the gable apex over the main portal (see alongside), as well as the intricate ironwork of the wooden door, restoring the latter where necessary. He also kept the top row of medieval figures on the west front. But the design of the six-light west window with its Decorated tracery, and "the stage above it," are both his (Pevsner 179). The listing text dates the window to 1868; Pevsner dates it to 1869. The statues within the porch [close-up] are Victorian too, by Mary Grant. The Virgin Mary with the infant Jesus stands in the centre of the doors, with St Mary Magdalene to the left, and St Peter, holding his key, at the right-hand corner of the return. The figure on the façade immediately to the left has been identified as that of St Andrew (see Scaife's key on the back cover).

Left to right: (a) Close-up of St Chad in the centre of the second row of statues. (b) The south-east corner, with Edward the Confessor above a female saint. (c) The north-west spire seen from the south side.

St. Andrew and the other external figures, most of them on the west façade, were produced locally by the Lichfield firm of Robert Bridgeman & Son, which also worked on Basil Champney's Rylands Library in nearby Birmingham. Pevsner dates them to 1876-84, "replacing cement or stucco statues of 1820-2" (179n.). These include the kings of England [close-up] ranged on either side of St Chad. The monarchs were brought up to date, and include Queen Victoria, further to the left in the row above, sculpted by her daughter Princess Louise. Another good female figure is the pensive saint standing beneath Edward the Confessor [close-up]. From the south side, it is easy to see the four tiers of lucernes on the north-west spire, the flying buttresses (their slate tops now green) and the clerestory windows with trefoils in the geometrical tracery. Scott himself explains that the south side had already been restored by Smirke (297).

At the south-east end, the exterior of the Lady Chapel, a later addition by medieval builders when lengthening the east end of the cathedral.

The Lady Chapel is the same height as the chancel itself, and has a polygonal end, "a form frequent on the Continent, but very rare in England" (Pevsner 180). Notice the parapets, tall windows of three or five lights with beautiful tracery, and more statues in niches on the buttresses. In the wall below are three tomb recesses, the carved forms of which date the fabric of this part to about 1310. On the inside, there are three tiny chapels, with crypts "or rather boneholes" beneath them (Pevsner 183n.).

The gargoyle shown to the right here is on one of the buttresses at the corner, and looks freshly carved. The work of restoration never ends and collaboration continues across the centuries.

Related Material

References

"The Cathedral Church of the Blessed Virgin Mary and St Chad, Lichfield." British Listed Buildings. Web. 26 June 2013.

Clifton, Arthur Benjamin. The Cathedral Church of Lichfield: A Description of Its Fabric and a Brief History of the Episcopal See London: George Bell, 1898. Internet Archive. Web. 26 June 2013.

Pevsner, Nikolaus. The Buildings of England: Staffordshire. London: Penguin, 1974.

Scaife, Patricia. The Carvings of Lichfield Cathedral. Much Wenlock, Shropshire:R. J. L. Smith, 2010.

Scott, Sir George Gilbert, R.A. Personal and Professional Recollections, edited by his son, G. Gilbert Scott, F.S.A. London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle, & Rivington, 1879. Internet Archive. Web. 26 June 2013.

Welcome to Lichfield Cathedral. Short but informative guide available at the cathedral.

Last modified 26 June 2013