All photographs are by the present author, who has also kindly supplied the scans of other material. You may use them without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one. Click on all images to enlarge them. Formatting and perspective correction by Jacqueline Banerjee

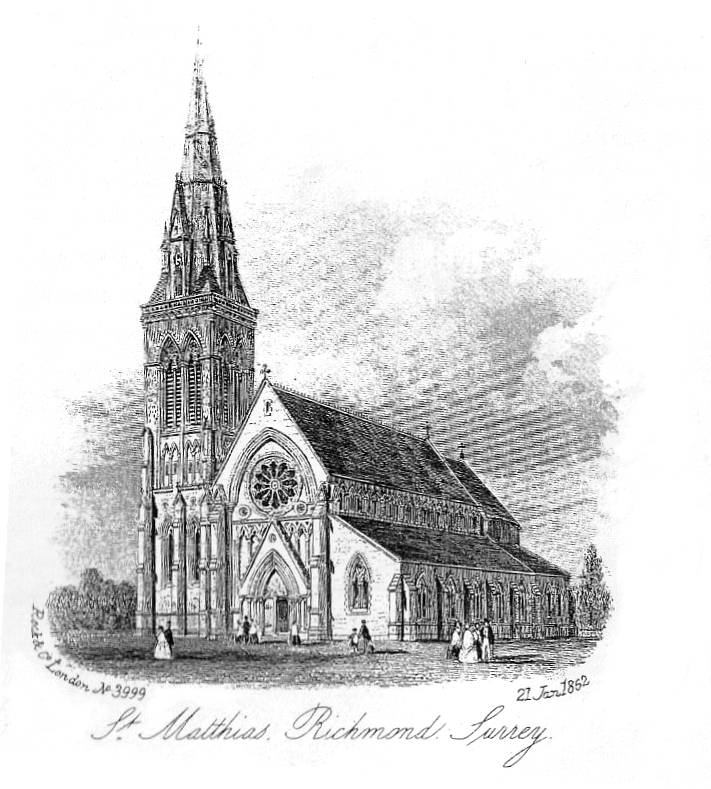

St Matthias' Church, Richmond, Surrey. Sir George Gilbert Scott. 1858-62. Engraving: Rook & Co. 21 January 1863 (Local Studies Library Collection, Richmond)

“It will be, when completed, the chief ornament of Richmond. Since the destruction of Henry the Seventh’s Palace, no public building has been seen in Richmond to compare with this. The Fund is nearly exhausted, and there is danger that the work must be suspended, unless further help is given.” — "Parish News," Richmond Parish Magazine, October 1861.

Introduction

t. Matthias' Church in Richmond, Surrey, was created as a chapel of ease to serve an expanding community in the mid-nineteenth century. It was to be built to the design of renowned Victorian Gothic Revival architect Sir George Gilbert Scott, and expectations were high. The church was described as a "striking object" before it was even complete: it was to be the town's "pride and ornament" for generations to come (Dupuis). Inevitably however, the design would not please all. Shortly after its construction, the interior arrangements were deemed "somewhat chilling" and gained St. Matthias an unfortunately scathing review (The Ecclesiologist, 343). What caused these diverging opinions, who initiated them, and would knowing that reveal the reason for such opposed attitudes towards the church's design? What style of "Gothic" did Scott employ at St. Matthias, and what produced the so-called disagreement between its interior and exterior plan? Indeed, how have such contrasting criticisms affected the very perception of the church, and were they so powerful as to influence the manner of future restoration work in rectifying its allegedly cold, lifeless interior? This essay will investigate these issues through an analysis of Scott's medievalism that took shape in the Church of St. Matthias, and it is hoped that exploring its raison d'être and bearing on the local community will reveal a number of interesting points. The legacy the church left to the town in terms of its visual and symbolic impact will also be briefly considered.

t. Matthias' Church in Richmond, Surrey, was created as a chapel of ease to serve an expanding community in the mid-nineteenth century. It was to be built to the design of renowned Victorian Gothic Revival architect Sir George Gilbert Scott, and expectations were high. The church was described as a "striking object" before it was even complete: it was to be the town's "pride and ornament" for generations to come (Dupuis). Inevitably however, the design would not please all. Shortly after its construction, the interior arrangements were deemed "somewhat chilling" and gained St. Matthias an unfortunately scathing review (The Ecclesiologist, 343). What caused these diverging opinions, who initiated them, and would knowing that reveal the reason for such opposed attitudes towards the church's design? What style of "Gothic" did Scott employ at St. Matthias, and what produced the so-called disagreement between its interior and exterior plan? Indeed, how have such contrasting criticisms affected the very perception of the church, and were they so powerful as to influence the manner of future restoration work in rectifying its allegedly cold, lifeless interior? This essay will investigate these issues through an analysis of Scott's medievalism that took shape in the Church of St. Matthias, and it is hoped that exploring its raison d'être and bearing on the local community will reveal a number of interesting points. The legacy the church left to the town in terms of its visual and symbolic impact will also be briefly considered.

The new commuter town of Richmond-Upon-Thames, a fashionable town famed for its "pleasant riverside setting" and historic royal associations, expanded rapidly during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. The arrival of steam in 1816 made the area much more accessible, and the number of new residents steadily rose (Cloake, Richmond Past, 69). By the 1820s, the original Parish church situated in the heart of the town, the historic St. Mary Magdalene, was hard-pressed to accommodate an ever-growing congregation (Cloake, "Richmond Parish Church"). This was eventually recognised by the Vestry as necessitating the building of a new chapel. Eminent local resident and landowner, William Selwyn Q.C. (1775-1855), generously offered a site from his sizeable estate for the proposed new church. The design was formally underway by 1831, and the new chapel became a reality as the Church of St. John the Divine (Cloake, Richmond Past, 92). In 1838, this became the Parish Church due to the town's new status as a separate parish (Velluet 3). This new chapel, although certainly relieving the pressure on St. Mary Magdalene, did not prove a lasting solution.

The arrival of the railway in 1846 eventually transformed Richmond into a new commuter suburb, resulting in an ever expanding community, particularly the vicinity near Richmond Hill (Exhibition, "The Railway Age"). The middle classes flocked to the developing area from the city, attracted by the town's prestigious history, idyllic setting, and close proximity to London, merely ten miles away (Cloake 7). The population virtually doubled from 4,628 in 1801 to 9,255 in the mid-1850s (Cloake, Richmond Past, 88), and soon after 1852, negotiations commenced regarding the creation of a further new chapel in Richmond (Velluet 3).

The New Church

In a public meeting held at the Boy's National School Room on 18 May 1855, it was finally resolved that a new church would be built for the "rapidly increasing District upon the Hill." The necessary funds for its construction were to be raised through voluntary contributions from the public, as opposed to a "fixed church rate," in the sum of "not less than £7,000" in addition to donations "promised or made" by members of the Committee totalling £2,898 (Richmond Vestry Meeting Notice, 1855). William Selwyn chaired the meeting, and again offered to donate land for a new church; but he died soon after the meeting, his offer seemingly overlooked. Eighteen months later, after a series of costly delays and fruitless negotiations, the wheels were at last set in motion in July 1857. Prominent Richmond resident Charles Jasper Selwyn Q.C. (1813-1869), fourth son of William Selwyn QC and future Lord Justice of Appeal, formally donated a site from his own vast estate to the Ecclesiastical Commissioners "to be devoted when consecrated to ecclesiastical purposes forever" (Velluet 4).

The choice of Sir George Gilbert Scott as architect of the new church was in many ways a natural one. His tireless work in creating and restoring hundreds of churches across England had gained him many accolades in the 1850s, not least for his work in the Gothic Revival style (Clark 175). Moreover, he had both social and professional connections with eminent local residents, including William Selwyn and Reverend Henry Dupuis, the first Vicar of Richmond (Velluet 4).

St. Matthias, Concept to Reality

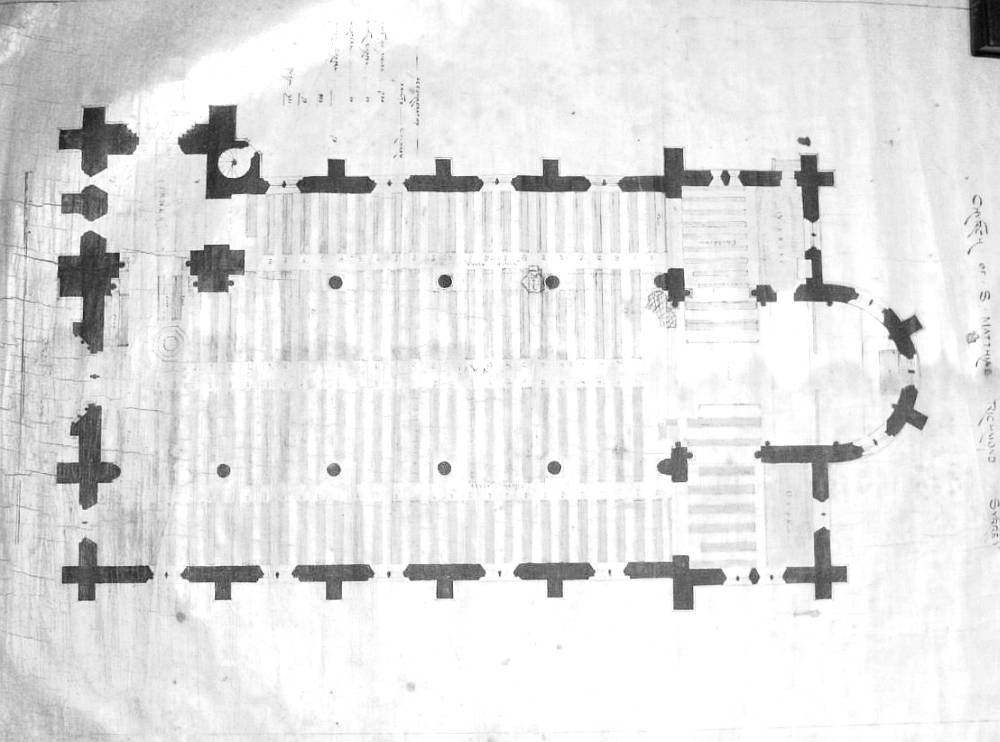

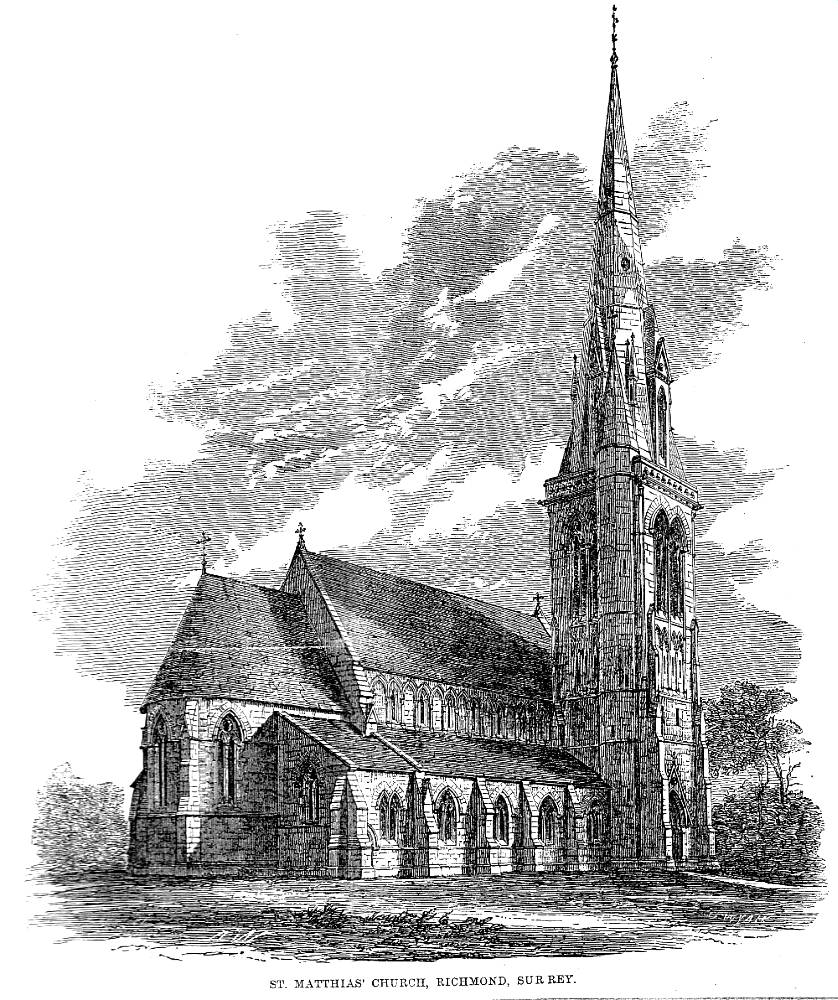

Left: Ground plan, showing proposed arrangement of pews. Original contract drawing from the office of Sir George Gilbert Scott, held at the St Matthias' Church archives. c.1857-58. Right: Engraving of St Matthias' Church by J. D. Wyatt, 1858 in Illustrated London News, 21 August 1858, p. 174. Local Studies Library Collection, Richmond.

Charles Jasper Selwyn Q.C. finally laid the foundation stone for the new church in a grand ceremony on Tuesday 14 April 1857, attended by approximately 2,000 townsfolk (Illustrated London News, 1858). The contract for the initial stage of building was awarded to Messrs. Piper & Sons of Bishopsgate Street, London, and construction soon followed. The church was erected within sixteen months, an admirable achievement considering the large scale of its design, with enough seating for 921 people (Velluet 4).

Consecrated as St. Matthias on 7 August 1858, and despite the still incomplete tower and spire, the church was described in the Illustrated London News merely two weeks later as a "striking object far and near in the landscape" (174). The atmospheric engraving of St. Matthias by J. D. Wyatt alongside the article exemplifies such high regard. Expectations were indeed high. Reverend Henry Dupuis felt keenly the aesthetic and architectural importance of St. Matthias, and was eager for its structure to be finished. As Chairman of the Committee for the St. Matthias' Church Building Fund, Dupuis appealed to the public in June 1861 for additional funds to complete its tower and spire: "An ecclesiastical edifice of such strength and excellence is necessarily costly; but it has been the opinion of the Committee ... that the importance of the locality and the singular beauty of the site, justified them in adopting a design ... which would be the pride and ornament of Richmond for many generations."

Numerous donations were received, and four months later, the tower was noted as "quickly rising." The capstone of the spire was eventually laid by Reverend Dupuis on 21 August 1862 (Velluet 5). The event was briefly recorded in the September issue of the Richmond Parish Magazine, which declared that "this noble Church ... has been completed," further quoting Reverend Dupuis' prayer as the stone was set down: "I lay this stone to the glory of God in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost; and may all who have helped forward this building, or who have laboured with their hands to erect it, dwell in the eternal church of God in heaven, through Jesus Christ" ("Parish News"). To mark the occasion, the "Royal Standard was raised and a salute of twenty one guns fired." The efficiency of the whole project was outstanding, and the cost of the completed church totalled £10,073 (Velluet 5), very much on target with the initial proposed sum of £9,898.

Plan and architecture

Left to right: (a) South-west corner today, showing weathered Kentish ragstone rubble. (b) c.1857-58. Latitudinal cross-section through chancel, nave and aisles. Original contract drawing from the office of Sir George Gilbert Scott, held at the St Matthias' Church archives. (c) Longitudinal cross-section, as referred to in The Ecclesiologist (1868): XIX, 343. Original contract drawing from the office of Sir George Gilbert Scott, held at the St Matthias' Church archives.

The church as it finally stood comprised a solid structure, built with materials of "typical Victorian construction"(Interview, Velluet, 2010). London Stock brickwork was employed for the core, tower and a few other areas of the church, and was faced with squared Kentish ragstone rubble. Bath Stone from the Box Hill quarry was used for the main features and dressings, including the exterior sculpture detailing, as well as the spire, decorated with pinnacles and parapets (Velluet 8). The use of Kentish ragstone as a "veneer" for the cheaper core of London Stock brickwork was common during the period of economic church building in Victorian Britain. These materials, perhaps unsuitable for use in London, show considerable wear at St. Matthias today.

The plan, as first designed, constitutes a large nave with piers forming the north and south aisles at either side. The twenty-four-foot wide apsidal chancel is flanked by aisles correspondent to those of the nave. The generous height and proportions of the structure are clearly illustrated in the original elevations of the church.

Left: St Matthias' Church, west façade, showing triple buttressing at the northwest tower. Right: Detail showing distinct tracery of wheel window.

Paul Velluet, local resident and architect specialising in conservation, has long been involved with St. Matthias. Velluet describes Scott's design as a "direct crib" from those of the great Northern French medieval cathedrals, and the juxtaposition with Early English elements as somewhat "paradoxical." Looking at the church from the outside, leitmotifs of thirteenth-century English and French medieval cathedrals are certainly clear. An outstanding example of Northern French influence is evident in the use of triple buttressing at the lower section of the tower, which bears a striking resemblance to the lower half of the twelfth-century southwest tower of Chartres Cathedral. Velluet further parallels the distinct tracery work of the West wheel window at St. Matthias with thirteenth-century Northern French precedent. As the name suggests, such tracery resembles the spokes of a wheel, radiating from a central boss or roundel (Stevens Curl 137). More elaborate examples are evident at the early gothic cathedrals of Strasbourg, Notre Dame in Paris, and Chartres. The wheel window at St. Matthias, however, seems rather more similar to Italian Romanesque and medieval cathedrals, such as those at Puglia.

Romanesque buildings in England are described as Norman in variety (Stevens Curl 135), the style preceding that of the Early English stage in Gothic design (Rickman). Notable examples of wheel windows in Britain which demonstrate a distinct likeness to the design at St. Matthias are clear at the Beverley Minster in East Yorkshire, Early English in style, with earlier Norman examples at the churches of St. Nicholas at Barfreston, and that of the same name at Castle Hedingham.

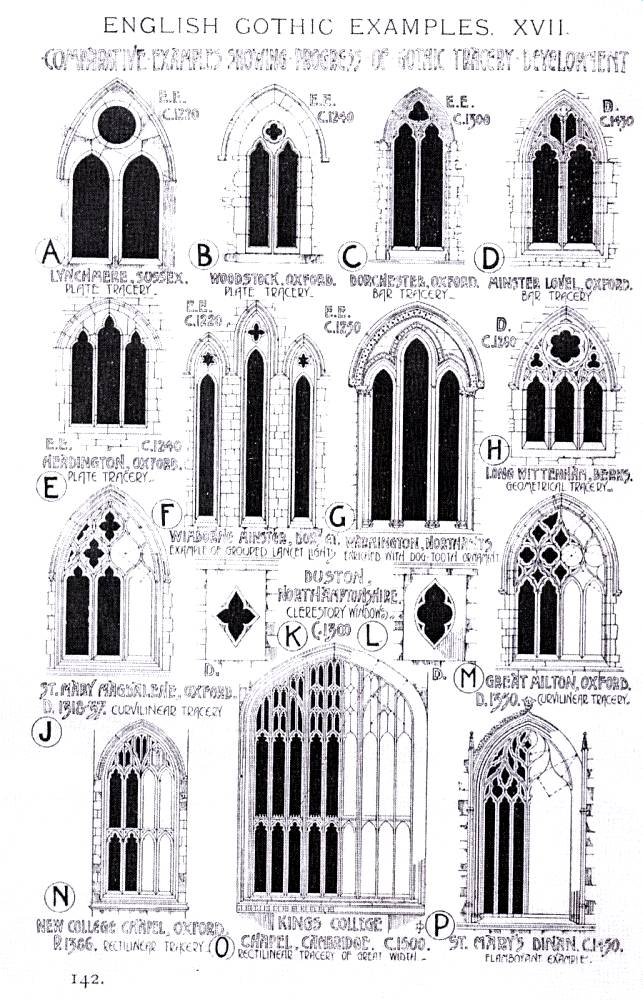

Left: South side now, showing exterior arcading at clerestory level. Right: "English Gothic windows," Sir Banister Fletcher, 1905. The two-light windows at B and C are similar to those at St Matthias. From A History of Gothic Architecture on the Comparative Method, plate 142.

The clerestory windows at St. Matthias illustrate the lancet style typical of Early English design. According to Pevsner, their exterior arcading is comparable to that of "Lincolnshire churches," most particularly All Saints' Parish Church in Stamford (519). The two-light windows surrounding the apsidal chancel at St. Matthias are Early English in style, while the cinquefoil motif incorporated above displays geometrical tracery characteristic of the later Decorated period.

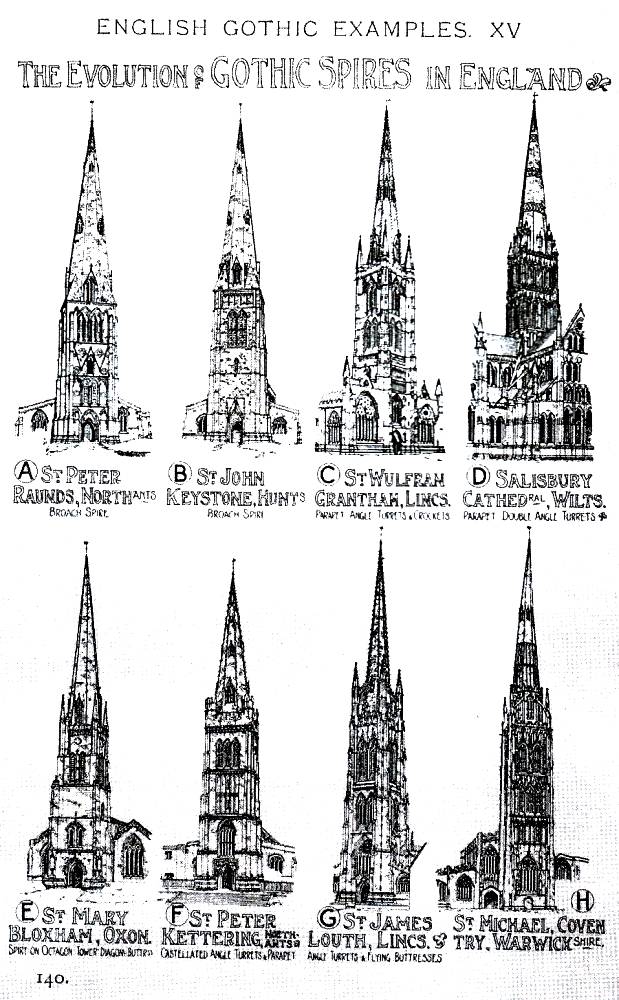

Left to right: (a) “The Evolution of Gothic spires in England,” From Sir Banister Fletcher. A History of Gothic Architecture on the Comparative Method (1905), plate 140. (b) The tower and spire of St Matthias's Church today. (c) "St Matthias' Church, Richmond." "The Proposed New Church, Richmond," as first designed by Sir George Gilbert Scott, 1857, showing the proposed southwest position of the tower and spire. Engraving, J.D. Wyatt. Local Studies Library Collection, Richmond.

Velluet suggests that the "general profile and proportions" of St. Matthias' broach spire reflect the design of the thirteenth-century West towers at Bayeux. Broach spires, usually conical in shape and protruding from a square tower, were also typical of the Early English style, normally without parapets. The broach spire at St. Matthias, however, encompasses parapets at each corner of its base, as at Stamford, but without crockets (Stevens Curl 135).

Such a "cross-Continental" collaboration of English, French, Italian and even German medieval styles would not have been unusual at the time, and in Scott's work, is most likely attributable to his many European travels. In addition, the Gothic style as it actually originated in twelfth-century France, particularly at St. Denis in Paris, before having even spread to England, was not commonly known at the time (Waterhouse). However, Scott's noteworthy restoration work in 1847 at Ely Cathedral would have acquainted him with its Dean, George Peacock, who was very enthusiastic about Amiens Cathedral (Waterhouse), no doubt predisposing Scott towards thirteenth-century Northern French design.

Upon examining the original contract drawings for St. Matthias, however, an interesting but puzzling point arises. The elevation of the West façade shows the situation of the tower at the southwest corner of the church, despite its construction at the opposite, northwest corner. Velluet notes the peculiarity of the initially proposed southwest position being maintained as far as the stage of the signed contract drawings, and speculates whether the alteration may be attributable to "concerns about the foundation conditions, or ... townscape factors" (8). Why the tower was eventually placed at the northwest corner is certainly perplexing. How exactly this change of position would have affected the church, and whether it was of any significance at all, is as yet unclear. Nonetheless, it did not detract from the spire's outstanding bearing on the town's skyline.

Overall, the general structure of the church was well regarded upon its completion. The Builder provided a review of St. Matthias in its issue of 7 August 1858 entitled "A new church at Richmond," describing it as "Geometrical Pointed, but ... by no means lavish in ornament ... with the exception of the west front, the effect of the design depends chiefly upon the boldness of its parts" (534). The design of the interior, however, was to prove far less pleasing to some.

The Interior

Left to right: (a) Norman piers. (b) Early English piers. Note the evolution towards a more clustered style. Both studies from Thomas Rackman, An Attempt to Discriminate the Styles of Architecture in England (1835), pp. 51, 127. (c) St Matthias' Church, interior, early 20th century, showing addition of screen. Photographer unknown. Local Studies Library Collection, Richmond.

Velluet, in his brief history of the church, describes the interior as it probably looked at the time of its completion in 1858, as "austere, with plain plastered walls, minimal furnishing other than regularly-spaced, pitch-pine pews accommodating over nine hundred worshippers, and plain-glazed windows (9)." The interior, rather stark in appearance, displayed many gothic elements notable of earlier periods, such as the bare circular piers dividing the nave from the north and south aisles typical of the Norman style, which took on a more clustered form in the later Early English period.

However, such simplicity can be admirably attractive, and appropriate. The austerity of the thirteenth-century French and English gothic elements certainly work in complimenting the "boldness" of the structure. The gently pointed arches along the north and south aisles of the nave impart a sense of height appropriate to its interior dimensions. The plain, smooth, circular columns from which these arches spring conclude in capitals adorned with richly sculptured foliage, injecting life into the bare design without appearing unnecessarily ornate. The simple clerestory lancet windows lend an upward thrust to the bold, solid proportions (Stevens Curl 106). Although many significant medieval motifs were artfully implemented throughout St. Matthias, some critics were simply not as agreeable to its interior arrangements. In a review of the church shortly after its first stage of completion in 1858, The Ecclesiologist provided a characteristically unforgiving critique:

A new church, by Mr. G.G. Scott, in his characteristic style; bold and artistic in its treatment, but withal rather cold.... A little real Christian sculpture in the reredos, or ... anywhere else, in which the higher powers of our rising artists might be employed, would be far more to our mind; and we feel that we have some right to expect it in the works of one who has argued so ably for an improvement in that branch of art as has Mr. Scott."

The chancel opens into its aisles by Italianizing three-foiled arches ... though pretty in themselves, [these] seem to us rather disproportionately large for their form: and in fact, the least successful architectural feature of the design will be found, we think, in the want of harmony, or intelligible relation, between the elevations of the nave-arcades and the chancel walls, as shown in a longitudinal section of the church ...

The internal arrangements are commodious, but show no great improvement of ritual. The chancel levels are not bad, but there is no screen nor parclose, and the altar stands close to the eastern wall of the apse. There is no reredos whatever as yet, and this unhappily is the very barest part of a somewhat chilling interior. ... There is no attempt at colour in any part, except in two or three windows....

Upon the whole this church is convincing proof of the immense stride lately made among us in reviving a good style of Pointed design. But we want something more than coldly correct architecture — something that shall show convincingly that each particular design has been with its author not merely a routine example of office work, but a true labour of love. [342-43]

The Ecclesiologist essentially criticised St. Matthias for its lack of a suitably displayed "fitness of form to sacred function," a notion fervently espoused by the passionate Roman Catholic architect, Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin, a slightly earlier contemporary. In his Contrasts, Pugin enthused that "the fitness of the design to the purpose for which it is intended ... should so correspond with its use that the spectator may at once perceive the purpose for which it was erected" and claimed of the ancient medieval cathedrals that "each portion of them was destined for a particular use, to which their arrangement and decoration perfectly corresponded." Such ideals were taken up and adapted to Anglican principles in the mid-nineteenth century by the Cambridge Camden Society, the new "Ecclesiologists," in advocating their own philosophy of venerable church design (Neale).

Surely, however, buildings are not just art forms. Churches are indeed holy sites and should undoubtedly be designed to architecturally and decoratively honour their divine function. Nevertheless, it must be noted that a project such as St. Matthias, subject to real-life constraints of funding restrictions, planning and building complications, together with limited timeframes for construction, are those issues which would inevitably affect an architect's initial design concept, before a building has even been erected. In this light, factors of practicality and sound structural sense become the foremost priority. To assume every church would be able to personify such a desired sacred ambience purported by the Ecclesiologists is thus wholly unfair. Indeed, who is anyone to even evaluate a building without sound knowledge of the most fundamental aspect of an architect's profession, which, at its most basic level, is to get a building to stand up? Who is anyone to judge without having even erected a building himself? Further still, the decoration of St. Matthias would not have been complete at the time of The Ecclesiologist's review, an aspect seemingly sidestepped in its 'investigation'.

The distinction between the views of The Builder and that of The Ecclesiologist perhaps lies in their individual standpoints in the field of architecture itself. The Builder was a journal written by architects for architects ("George Godwin and The Builder"). Interestingly, it was the stinging article of the latter group that would have the greatest impact on the manner of future work to the church's interior. In due course, the "chilling interior" at St. Matthias was not to remain.

Internal changes

Some notable changes which occurred soon after the church's consecration in 1858 were to continue for the following two decades. These included the replacement of the "plain glazed, diamond-shaped" windows along the north and south aisles of the nave with those of richly coloured stained glass, designed by prominent Victorian stained glass designers such as Lavers, Westlake and Barraud, John Hardman and Company of Birmingham and William Wailes of Newcastle Upon Tyne (Velluet 14).

Less than four years after The Ecclesiologist's "attack," however, considerable enhancement to the interior fabric at St. Matthias began to take shape. The chancel ceiling, forming part of the most liturgically sacred area of the church, was described in the Richmond Parish Magazine of 1862 as "very beautifully and tastefully decorated with mural painting, by Messrs. Bell & Clayton. The chief features are the Sacred Monogram; a Sheaf of Corn and Cluster of Grapes, emblematic of the Holy Communion; the Creed; Lord's Prayer; and Ten Commandments" ("Parish News")

More than a decade later, following Scott's death in 1878, his second son, John Oldrid Scott, took on the role as Surveyor to the church. Markedly, it was he who first proposed major improvements to the church's interior. In 1884, Scott provided St. Matthias with a choir vestry, the first significant addition. Thereafter, in 1886, he drafted a detailed report to the Vicar and Churchwardens, documenting his examination of the church's condition, including numerous recommendations for changes to be carried out. His significant proposals for the addition of a "richly coloured and gilded" reredos to the altar, the establishment of screens to separate the chancel and the nave, as well as screens in the arches flanking the chancel (Velluet 9), seem to arise directly from The Ecclesiologist's 1858 review, which so bitterly described the internal structure with "no screen nor parclose" and "no reredos whatever as yet .. the very barest part of a somewhat chilling interior"(343).

Scott's many suggestions, however, were only brought to fruition in the early twentieth century by his successors, Arthur Blomfield and Cecil Hare, whose own noteworthy improvements included the formation of the All Saints Chapel in the original south chancel aisle in 1915. Hare was previously partner to George Frederick Bodley, the "distinguished Gothic Revival architect" who also trained with Scott (Velluet 9-10).

Some interior features were, however, particularly impressive, never requiring any improvement. The brilliant stained glass of the West wheel window was the work of the aforementioned renowned stained glass maker and designer, William Wailes of Newcastle Upon Tyne. The richly coloured glass, still evident today, depicts the twelve apostles with Christ in the central roundel, designed by Wailes in memory of the man who so passionately venerated the aesthetic, architectural and symbolic value of St. Matthias, the first Vicar of Richmond, Reverend Henry Dupuis (Velluet 14-15).

Scott's Medievalism

Contrasting the appearance of the church from early engravings with images from today, it is evident that very little has been altered, perhaps testament to its commendable design. The chequered history of the interior, however, subject to much renovation and change, assured the establishment of a much "warmer" ambience.

It cannot be doubted that the general style of St. Matthias, particularly that of the exterior, demonstrates work of a highly scholarly, archaeological correctness, echoing the motifs of the great cathedrals of the Middle Ages. Scott's recreation of a medieval ideal in his work, however, could not escape being coloured by the Victorian mentality. If the "ingredients" of his designs were of the past, the total effect was indeed of the time. Scott's choice and combination of motifs, his use of specific elements from medieval cathedrals rather than a copy of their entirety, put together with his own vision, exemplifies his originality and inescapably nineteenth-century mind.

In his Recollections, Scott readily acknowledges his leaning towards a more creative use of tradition, stating that, "In our church architecture we have, as I consider, little reason to depart far from our own types; though I confess, even here, to a tendency to eclecticism of a chastened kind, and to a desire for liberty to unite in some degree the merits of the different styles" (Personal and Professional Recollections, 228-29). Although Scott claimed to have been awakened by "the thunder of Pugin's writings" which excited him "almost to fury"(qtd. in Stamp), as well as having admired the principles of the Ecclesiologists, the manner in which he manifested such influences in his designs ultimately demonstrates his characteristic pragmatism in adapting past precedent to suit the needs of a modern society, far beyond eccentric philosophies and impossible ideals: "Our age is ... eminently antiquarian, and in the minute acquaintance with the history of past styles which we possess, we may find some amends for the want of one of our own"(An Essay on the History of English Church Architecture, 2).

It may be that St. Matthias' Church did not embody a desired liturgical resonance, or an "adequate" display of its sacred function, apparently further demonstrating its architect's not having performed a "true labour of love" in its creation. It may also be, however, that constantly to equate morality with architecture would have been crippling and unproductive in the social and economic climate in which Scott worked. In an age of increasing population coupled with a still-active tradition of churchgoing, Pugin's obsessive religious ideals thus seem all too totalitarian, and those lofty principles of the Ecclesiologists highly unrealistic.

In fact, given the time or money, would St. Matthias have looked any different? Without restraints of deadlines or the need to appeal for voluntary contributions, would unlimited time and funding necessarily have produced a much grander design? Another of Scott's commissions, St. Stephen's in Lewisham, a church contemporary with St. Matthias, proves revealing in this light. Begun in 1863, it was "unlimited as to cost" ("Southwark Parish Church"). Interestingly, although built without funding constraints, it is simply not as grand as St. Matthias. The proposed tower and spire, even though intended at the outset, were never carried out at St. Stephens. This was undeniably the fate of many churches at the time, and at St Stephen's was "owing to the nature of the site," something that no amount of time or money could rectify. The aesthetic outcome, however, would have an everlastingly detrimental effect on its appearance.

Conclusion

St. Matthias' Church as it is today. Left to right: (a) Approaching the north side. (b) Northwest corner (c) Distant view from Richmond Park.

Overall, did it matter that Scott built St. Matthias economically? Did it matter what specific brand of "Gothic" was employed in its design and plan, and whether it suitably accommodated its liturgical function? Despite the fact that the church was built quickly and cheaply, aspirations for its design were still high. Scott's allusions to great medieval cathedral design, the architectural quotations from Bayeux and Chartres, or even from All Saints' Church in Stamford, form the visual elements which lend the most grandeur to St. Matthias. They demonstrate Scott's ingenious approach to 'the Gothic, breathing new life into traditional medieval cathedral design. The reason behind the mysterious change in the position of the tower and spire may indeed never be known, but it may well have improved its magnificent bearing upon the Richmond skyline, its majestic situation only further enhancing its visibility for miles around.

The importance of such an edifice as St. Matthias is in fact more than merely aesthetic, and it should not be judged by whether it measures up to what seem rather fanatical ideals of church craftsmanship. The impact of St. Matthias on the community of Richmond has proved long-lived, for there have been consistent efforts to preserve its heritage throughout the twentieth century, and it has continued to serve this community, having enjoyed "uninterrupted use for public worship" since its inception (Velluet, 3). Scott's St. Matthias has gone from strength to strength throughout its history. In an endeavour markedly similar to that of Reverend Dupuis in 1862, the celebrated naturalist and BBC broadcaster Sir David Attenborough, himself a long time-resident of Richmond, led a public appeal in the late 1970s to raise funds for essential restoration work to the spire of St. Matthias. Attenborough, providing valuable celebrity backing as Patron of the appeal, displayed a profound belief in the value of the church in today's society in a moving account, stating that: "Today more than ever we need the inspiration of buildings such as Saint Matthias which, as we see its spire on top of the hill from Chiswick Bridge, from Richmond Park, or from a hundred other viewpoints as we pass through Richmond, has the ability to lift our hearts and minds above the materialistic pressures of our busy lives" ("St Matthias Appeal"). The church now gives its name to the St. Matthias Conservation Area, as designated by the Local Authority in 1977.

It is perhaps no wonder that St. Matthias was once even compared to a royal abode. Shortly before the completion of its imposing spire back in 1862, the Richmond Parish Magazine dramatically equated the potential grandeur of St. Matthias' Church to the seat of a king, in that "Since the destruction of Henry the Seventh's Palace, no public building has been seen in Richmond to compare with this" ("Parish News"). Yet, with the advantage of today's historical perspective, how is Scott's St. Matthias viewed in light of the widely acclaimed architectural work of the Gothic Revival period? In recent years, it has been said that "Richmond produced no building of the Gothic style to match the detail and perfection of Horace Walpole's Strawberry Hill" (Cloake, Richmond Past, 65). To my mind, Walpole's more light-hearted, "primitive" interpretation of "Gothick" is no match for Scott's Gothic at Richmond. Scott's medievalism found its form in a far less frivolous affair at St. Matthias, exemplifying perhaps a more authentic medieval style, a particular brand of Gothic unmistakably that of the "broad-church Anglican" (Stamp) and self-confessed Gothic revival architect "of the multitude" (qtd. in Stamp).

Related Material

- St. Matthias' Church, Gallery I: Exterior

- St. Matthias' Church, Gallery II: Interior

- Arthur Blomfield's chancel screen

- Windows in the church by William Wailes

- Windows in the church by John Hardman

- Windows in the church by Burlison & Grylls

- A window in the church by Lavers & Barraud

Primary Sources (unpublished)

Attenborough, Sir David. "St. Matthias Appeal." The Friends of St. Matthias, 1988. St. Matthias File, Local Studies Library, Richmond, Surrey

Dupuis, Rev. H. Appeal Notice, "St. Matthias Church Building Fund," June 1861. St. Matthias File, Local Studies Library, Richmond, Surrey.

Richmond Vestry Meeting Notice, 18 May 1855. St. Matthias File, Local Studies Library, Richmond, Surrey.

Richmond Vestry Minutes Book, January 1853 — August 1863. 23 July, 13 August, 17 December 1855; 18 February 1856. Pp. 114, 116, 136-37, 146-47. Catalogue Number: R/V/16: Local Studies Library, Richmond, Surrey.

Primary Sources (published)

Builder, The. "New Church at Richmond." Vol.XVI, London, 7 August 1858. Private collection. Paul Velluet RIBA, IHBC, Chartered Architect — Conservation, Development and Planning, Twickenham, Middlesex.

Ecclesiologist, The. "St. Matthias, Richmond, Surrey." Vol. XIX, Cambridge Camden Society, 1858: 342-3. Private collection. Paul Velluet RIBA, IHBC, Chartered Architect — Conservation, Development and Planning, Twickenham, Middlesex.

Illustrated London News. "New Church of St. Matthias, on Richmond-Hill," 21 August 1858, p. 174. St. Matthias File, Local Studies Library, Richmond, Surrey)

Neale, J. M. A Few Words to Church Builders. Cambridge, 1841.

Pugin, A.W.N. Contrasts; or, A Parallel Between The Architecture of the 15th and 19th Centuries London, 1836.

Richmond Parish Magazine. "Parish News," July, October, November 1861; September 1862 Local Studies Library, Richmond, Surrey.

Rickman, T. An Attempt to Discriminate the Styles of Architecture in England from the Conquest to the Reformation. 1819. Oxford and London, 1835.

Scott, Sir G. Gilbert RA. Personal and Professional Recollections. Ed. G. Gilbert Scott FSA. Sampson Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington, London, 1879.

Scott, Sir G. Gilbert RA. An Essay on the History of English Church Architecture Prior to the Separation of England from the Roman Obedience. London:Simpkin, Marshall, London, 1881.

Oral sources

Meeting and interview, Paul Velluet RIBA, IHBC (Architect — Conservation, Development and Planning) with author. St. Matthias Church, 26 July 2010 at 11a.m.

Exhibitions

"The Railway Age." Permanent display, Richmond Local History Museum. Richmond Town Hall, Surrey.

Secondary Sources

Clark, K. The Gothic Revival: an Essay in the History of Taste. 3rd Edition. London: Murray, 1974.

Cloake, J. "Richmond Parish Church: Richmond Retrospect." Richmond and Twickenham Times. 7 August 1987.

_____. Richmond Past. A Visual History of Richmond, Kew, Petersham and Ham. Historical Productions Ltd, 1991.

"East Lewisham Deanery: St Stephen with St Mark." Web. 19 August 2010.

"George Godwin and The Builder." City of London Archives, Information Leaflet No. 22). Also online here.

Pevsner, N. and Cherry, B. The Buildings of England, London 2: South. London: Penguin, 1994.

Stamp, G. "Scott, Sir George Gilbert (1811-1878)." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Volume 49. Oxford: Oxford University Press, September 2004.

Stevens Curl, J. Victorian Churches. London: Batsford, 1995.

Velluet, P. RIBA, IHBC. St Matthias’ Church, Richmond. A Guide and History. The Friends of St. Matthias, 2008.

Waterhouse, Paul. "Scott, Sir George Gilbert (1811£1878), Architect." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Online ed. Web. 19 August 2010.

Last modified 10 November 2016