In the old days, the then celebrated artists — the Holbeins, the Durers, the Clouets, the Cellinis, — did not disdain to design ornaments . . . and many other things; but now, when our chief artists do disdain so to employ themselves, the jewellers act in the best and wisest spirit when they reconstruct after the ancient models.

n this passage Mrs Haweis does less than justice to the artists of her time many of whom, like Maclise, Pugin, Burges, Millais, Rossetti, Ricketts, and Burne-Jones made charming and original designs for jewellery, a number of which were made up and remain amongst the most experimental designs produced during the nineteenth century. The reason that such a small amount of commercial jewellery made before the nineties was designed by artists may well be the lack of enlightened patronage. Few were so fortunate as Burges in having such a wealthy and imaginative patron as the Marquess of Bute. Mrs Haweis also appears to underestimate the considerable influence that these artists had on fashion, on jewellery even more than on dress where the influence of the more 'advanced' painters was limited to the Bohemian circle, through the accessories used in their pictures. For instance, the mediaeval mania which had started in the early nineteenth century with the popularity of Walter Scott's historical novels, was given a new lease of life by the works of the Pre-Raphaelite painters, and the exotic jewellery worn by the models in the later portraits by Rossetti were responsible for the popularity among the Aesthetes of all kinds of Oriental jewellery. The types of jewellery particularly associated with the Aesthetes are the long strings of beads, preferably of amber or jade, the Indian jewellery recommended by Mrs Haweis in the Art of Beauty, jewellery in the Japanese style decorated in cloisonné enamel or inlaid [139/141] designs, or antique jewels which were not admired then as they are now, which come straight from Rossetti's later portraits (Plate 67 & 68). In spite of the suggestion put forward in a Punch cartoon in 1878 I have only once come across a jewellery design inspired by the mania for blue and white china which was the consuming passion of the true Aesthete, a set in enamelled gold, consisting of a brooch, a pair of studs and a pair of earrings made of tiny little 'willow pattern' plates, sold by Alfred Pegler of Southampton.

Artists and Aesthetes alike were united in one thing, they

believed that the spread of mass-production was utterly

debilitating to design and invention in the decorative arts and that

the products of the Victorian factory were absolutely

unacceptable for the decoration either of one's home or one's

person. It was this conviction, backed up by their low opinion of

the exhibits at the Great Exhibition in 1851 which led to the

formation in 1861 of Morris, Meade, Faulkener and Co., the firm

founded by William Morris in association with some of his

Pre-Raphaelite friends which was destined to have such a profound

effect on late nineteenth-century design and great influence on the

decorative art of the present day. As a result of the introduction

of aniline dyes in the late fifties clothes had become very garish,

one fashionable colour in the sixties was 'magenta', an unwearable,

but unfortunately not unworn, shade of purply-crimson, and the

jewels designed to go with the vast crinolines which were in vogue

at the time were large and brightly coloured. To people of artistic

pretensions whose preference was for the soft, quickly fading

colours of the old vegetable dyes, and small delicately coloured

jewels, these strident ensembles, soon to be mercilessly illuminated

by the glare of the newly introduced electric light, seemed

distressingly tasteless. The conviction that these manifestations of

nineteenth century industrial prosperity were both tasteless and

vulgar came to be held by an increasingly large number of people

and they were fortunate in having two shops where they could

indulge their aesthetic ambitions in dress and decoration. Both

these enterprises, the decorating firm founded by William

Morris

and the shop opened by the former manager of Farmer and

Rogers' Oriental Warehouse, Arthur Lazenby Liberty, who sold

among other goods of Eastern origin, Indian jewellery and enamel,

were inspired by contact with the Pre-Raphaelite painters.

[141/142]

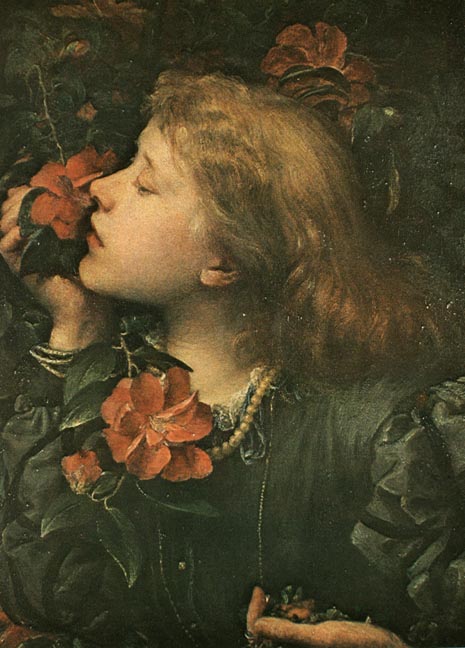

Plate 68. Rosa Triplex Triple portrait of May Morris, by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1874. Courtesy of Mrs. Virginia Surtees. Some of the jewellery in this picture seems to have belonged to Rossetti since it appears in other works, but the necklace on the right-hand figure was owned and possibly even made by May Morris herself.

Pre-Raphaelitism was a logical development of many current trends in English and European painting in the early nineteenth century, the early works of the Pre-Raphaelite painters most closely resembling the work of the German Nazarenes, whose work was similarly archaic in style, but in spite of this their paintings were originally greeted by a flood of ridicule. They were fortunate in having an influential champion in John Ruskin, whose admiration for their work did much to make them widely popular, but ironically enough they came to be most admired after all but one had foresaken the more revolutionary precepts and had largely abandoned the demanding techniques of their early works. [142/143]

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood originally had seven members, three of which had some place in the history of late nineteenth century jewellery design, William Holman Hunt , Dante Gabriel Rossetti and John Everett Millais . They were later joined by two men who had a great influence on late nineteenth century decorative art and thus inevitably on jewellery design, William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones .

Marillier, Rossetti's biographer, said of him, 'Rossetti, in spite of his indifference to the outside public, had a wonderful way of infecting it with his own predelictions and taste.' It is true that he and his companions had no thought of influencing fashion in the Rue de la Paix sense of the word, but the fact remains the aesthetic style in dress was based on the costumes worn in their pictures, a style which they had already persuaded many of the women in their own circle to adopt, and which did have a considerable impact on fashion. Mrs Haweis remarked in The Art of Beauty that the Pre-Raphaelites had made a certain type of face fashionable, a type which had previously been considered perfectly hideous. Not that she particularly admired this type, writing in 1879, 'All the women looked wan, untidy, picturesque, like figures of Pre-Raphaelite pictures with unkempt hair'.

Choosing by George Frederic Watts. 1864

The dress worn by Ellen Terry for her marriage to G.F. Watts in 1864 was designed by Holman Hunt and can be seen in Watts' portrait of his wife, called Choosing, now in a private collection. The dress is made of brown silk, decorated with a lattice design of velvet ribbon reminiscent of the dress worn by Sidonia von Bork in Burne-Jones' picture which is in the Tate Gallery. Ellen Terry is wearing a necklace of cloudy yellow beads and a long gold chain round her neck, which anticipate the Aesthetic fashion for simple jewellery which was to come ten years later. Photographs of Mrs Morris and Rossetti's model, Marie Spartali (Mrs Stillman), show that they wore clothes based on mediaeval dress and strings of beads but at this date few people outside the small circle surrounding the Pre-Raphaelites and such avant-garde artistic figures as Edward Godwin and Whistler were tempted to wear such outre costumes. The Aesthetic teagowns purveyed by Messrs. Liberty and Co. in the eighties had basically the same proportions as the more commonplace fashions of the time, though they have some claim to originality in the use of soft fabrics and in the [143/144] absence of elaborate braided decoration. Apart from the ubiquitous beads, Indian jewellery was considered suitable and artistic, being the absolute antithesis of mid-Victorian middle-class taste, which inclined towards the more elaborate mass-produced jewellery which had by now reached a high degree of precision and speciously meticulous finish, almost any kind of decoration from Gothic to rocco being applied by machine. Indian jewellery of the type imported by Liberty's was mostly bazaar jewellery of traditional design, a lack of symmetry and roughness of execution advertising the handcraftmanship which was its greatest attraction.

After the excitement which had been caused by the sight of the astonishing mechanical inventions which had been shown at the Great Exhibition in 1851 and the variety of things which they could produce, a certain element of disenchantment with machine-made ornament began to be heard. William Morris is reputed to have visited the Exhibition (he was then seventeen years old) and to have left after five minutes, driven out by an attack of nausea. His disgust took a practical form and in 1861 he founded the decorating firm mentioned above, Rossetti, Burne-Jones and the architect of Morris's house, Philip Webb, being among the original directors, with the intention of providing well-designed hand-made furniture which should be available to all classes of society. Morris's intentions were admirable but his knowledge of economics was non-existent and his wares inevitably remained the prerogative of the well-to-do, which was a great disappointment to him.

The rejection of mechanical aids to the production of jewellery had the same result on the price as in the case of Morris's furniture and fabrics. In spite of the fact that much of the jewellery made by the Guilds of Craftsmen, which came into existence in the final years of the century and were set up on the lines indicated by Morris and Ruskin, was made of semi-precious or flawed stones silver, copper or pewter, the necessity for carrying out every stage by hand made it impossible for the pieces which were made in this way to compete in price with the products of the Birmingham machines. In the few cases where the prices of this Arts and Crafts jewellery are known it does seem to be astonishingly cheap, but mass-produced jewellery, even at the beginning of the twentieth century, cost very much less. A lace-pin made of gold and pearls [144/145] might cost between seventeen and twenty-tive shillings, whereas a hand-made brooch of silver and moonstones would be three or four pounds.

In the same year that Morris and Co. came into existence Rossetti began to paint the large single figure subjects, full of jewellery, which were responsible for the fashion among the Aesthetes for unusual oriental or antique jewels. He was a customer of Liberty's when they first opened but it seems unlikely ilhat he acquired much of his large collection of exotic jewellery from there. Marillier has described the way in which he collected some of the bibelots and jewels which fill these later pictures.

'We are now entering upon the period (1861) when Rossetti ceased to paint small heads and began to devote himself to large single figure subjects, lavishing on them all the wealth of his fine imagination and surrounding them with quaint and beautiful accessories in the way of stamped leather or tapestry backgrounds, richly embroidered robes, inlaid pieces of furniture, jewels, vases, ornaments and flowers such as he alone knew how to select and paint. Many of these accessories, picked up during his rambles among the curiosity shops, figure over and over again in different pictures, the commonest of them all — so common that it almost amounts to a signature — being a spiral shell of pearls, worn at the side of the hair by his luxurious and languishing types of [145/146] beauty ... It was varied with other ornaments, a rosette and a pendant of pearls, large single jewels, gold and silver clasps, most of them are recognisable more than once . . . Of the other accessories which Rossetti used, the gold, amber, bead and coral necklaces, oriental stuffs, brass sconces and candlesticks, porcelain vases, ebony and ivory mirrors, jade toilette articles, and musical instruments such as would delight the antiquarian heart of Mr Dolmetsch, a very select and not inconsiderable exhibition might be made. One of the most striking objects in it, never so far as I am aware repeated, would be the brilliant scarlet side ornaments which the bride, in the picture of The Beloved, wears on her head to clasp her veil, which were made, I understand, of red Peruvian feather-work.'

Left: The Beloved by Dante Gabriel Rossetti. 1863. Right: Detail. Reproduced courtesy of the Tate Gallery.]

Some pieces of jewellery used by Rossetti in his pictures can be identified from amongst the jewellery listed in the catalogue of the auction sale which was held in his house after his death. The auction took place at 16 Cheyne Walk on the 5th, 6th and 7th July, 1882 and was conducted by T.G. Wharton, Martin and Co., of Basinghall Street. The second day's sale began with the 'Jewellery &c.' and one or two of the eighteen lots are identifiable as jewels used in various pictures. Lot 343, Chinese feather ornaments, is almost certainly the hair ornaments from the bride's veil in The Beloved. It is not unlikely that the autioneer's cataloguer would have confused these objects of reputedly Peruvian origin with Chinese work, since the feather ornaments are in the form of the Chinese 'jui-i', or 'fungus-head', found on Chinese sceptres as a symbol of longevity. The Chinese would have made these ornaments of blue and green kingfisher feathers and gold filigree.

Feather-work is a craft which has been practised in Peru since ancient times; copying Chinese ornaments like these would have presented no problems to the craftsmen. Since they would not be concerned with the traditional significance of the colours in the original ornaments, the Peruvian workers would naturally use the colours which are most common in their own feather-work, orange and red. This copying of feather-work was a well-established tourist attraction in the nineteenth century, and these ornaments may well have found their way to England in the baggage of a seaman, a route which accounted for the introduction into this [146/147] country of a large number of curiosities, including many exotic plants.

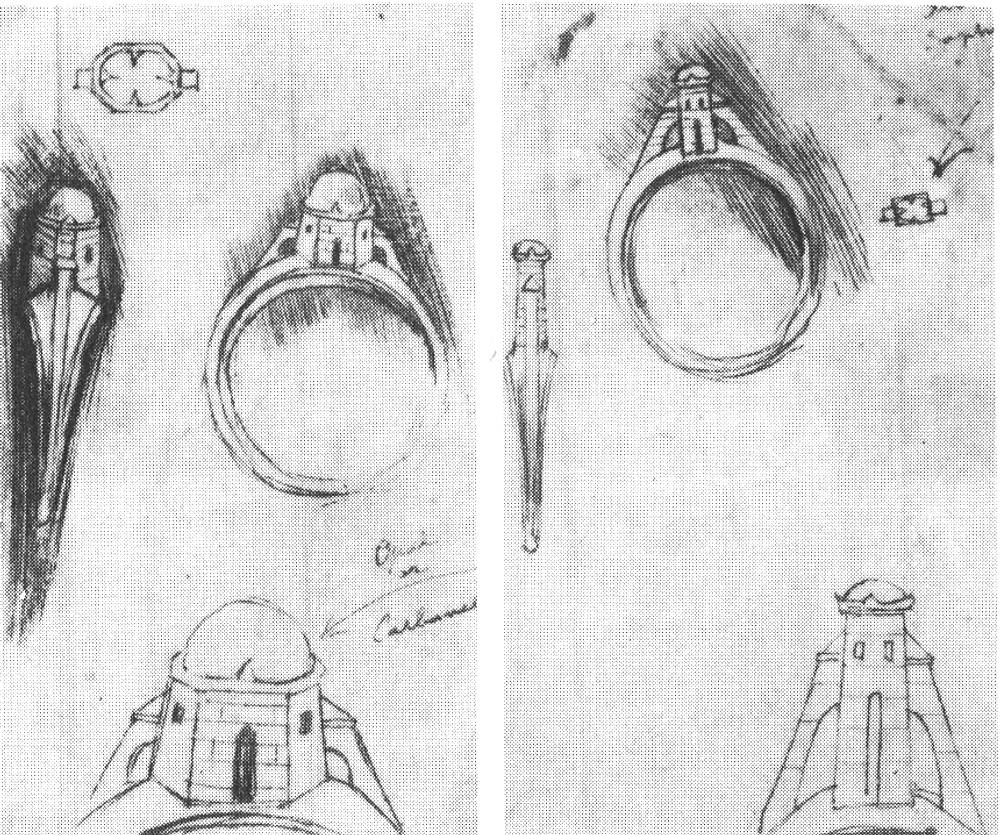

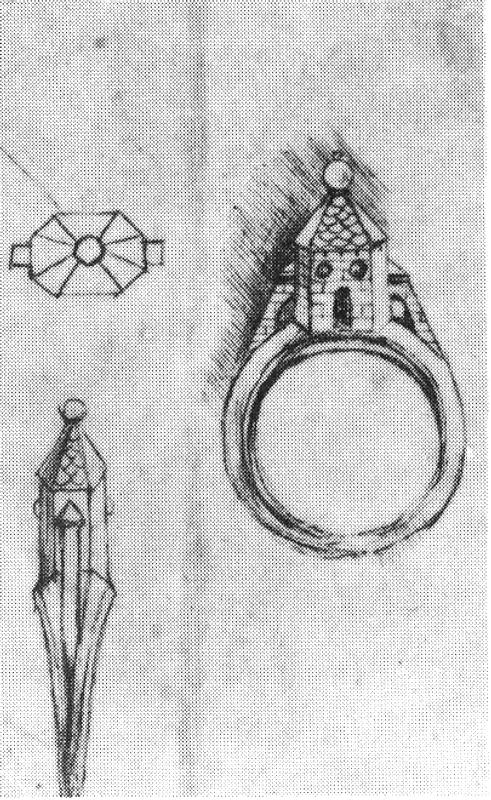

Plate 70a. Designs for a ring for May Morris by Charles Ricketts, 1899-1901. Reproduced courtesy of the British Museum.

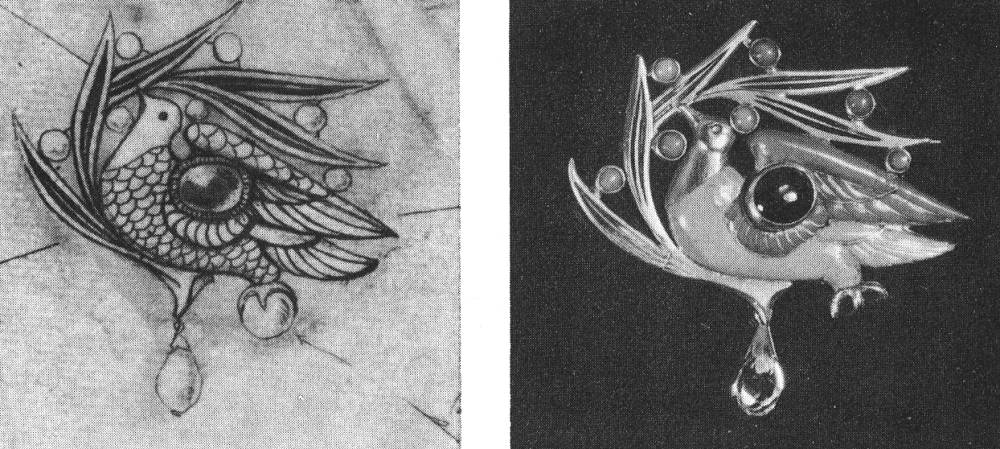

Plate 80a. Study for a brooch. Plate 80b. Right: Brooch in gold and enamel for 'Michael Field'. signed by Charles Ricketts, 1899. . Plate 80a reproduced courtesy of British Museum, 80b reproduced courtesy of the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge.

It seems likely that lot 352, Gold Indian ornament with pendants, is the large pectoral ornament worn by the slave-boy in the foreground of The Beloved, and some of the numerous other Jewels from this picture are probably in one or other of the many lots containing Indian jewellery which are listed in the catalogue. The Beloved (Plate 67) is full of exotic jewellery, Rossetti wrote to Mr Rae, for whom The Beloved was painted, saying 'I mean it to be like jewels'. How far he succeeded in this intention is open to [147/148] question,— his early water colours are far more jewel-like but it is certainly of jewels. Although Rossetti owned the majority of the jewels that appear in his pictures, a few of them were lent to him or owned by his models. An example is Fanny Cornforth's distinctive pendant earrings of two beads, a large one suspended beneath a smaller one. G.P. Boyce wrote in his diary of a visit to Rossetti's studio while The Beloved was in progress, where he saw that Rossetti had painted a jewel which he had lent to him on to the hair of the negro girl in the background. The right-hand necklace in the version of Rosa Triplex on plate 68 belonged to the sitter, May Morris, and it is possible that she designed and made it; she left it to her god-daughter, but it has since disappeared, vanishing in Paris in 1940 like so much else.

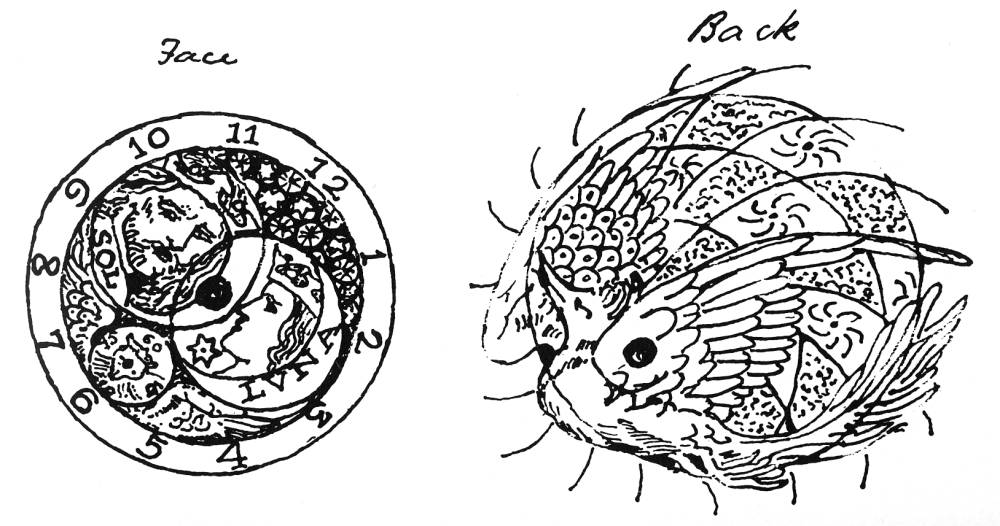

Plate 69. Designs for the front and back of a watch by Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Reproduced courtesy of the City museum and Art Gallery, Birmingham.

Rossetti's own jewellery designs reflect his taste for old or exotic objects. The face of the watch (Plate 69) is purely mediaeval in inspiration while the back has a distinctly Japanese appearance. The angel brooch (Plate 81) is like Gothic sculpture with over-tones of Pre-Raphaelite intensity in the expression, and had it been made would have been not unlike the Gothic jewellery of Froment-Meurice or Wagner.

Plate 81. Designs for a brooch by Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Reproduced courtesy of the City museum and Art Gallery, Birmingham.

The preponderance of the jewellery listed in the sale catalogue is Indian, a taste which Rossetti shared with some of his fellow artists. May Morris left some of her own and her mother's jewellery to the Victoria and Albert Museum and here a pretty Indian brooch keeps uneasy company with some rather coarse mid-nineteenth century filigree. In Holman Hunt's collection of jewellery described by Diana Holman Hunt, are some Indian things as well as the Fellahin jewellery (like the crown from The Bride of Bethlehem) which had'been made fashionable by Hunt's pictures done in the Holy Land. The artists and aesthetic people of this period (both Mrs Holman Hunt and Mrs Haweis) maintain the conventionally artistic or Ruskinian distaste for elaborate diamond jewellery, an attitude of mind which eventually gained so much ground that the hand-made jewellery of silver and semi-precious stones which was produced by the Morris-inspired Arts-and-Crafts societies founded in the late nineteenth century enjoyed an unexpected success, in view of the dominance of the diamond during the proceeding forty years. Jewellery made by May Morris herself is included in the collection which she left to the Victoria [148/149] and Albert, a buckle and chain set with moss-agates, garnets and pearls, c.1905; and an ivory comb mounted in silver set with mother of pearl and semi-precious stones made at the same time. May Morris received her training in design from her father, and in her jewellery which presumably embodies the whole Morris ethos in its design we have the nearest thing that exists to William Morris jewellery. The designs derive, in true Pre-Raphaelite fashion, from natural forms.

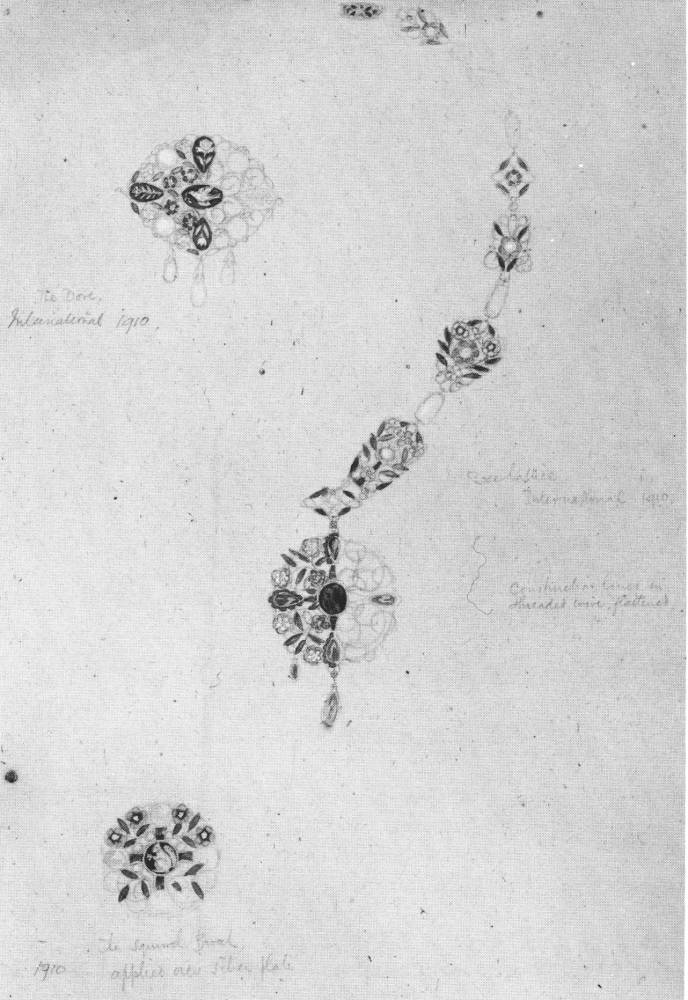

Left: Plate 71. 'Briar Rose' pendant and chain. William Morris, 1834-96, designer. Margaret Awdry, maker. Right: Plate 72. Designs for Jewellery including the necklace called 'Rose Lattice'. Arthur Gaskin. Reproduced courtesy of the Victorian and Albert Museum.

Although Morris studied metal-working he did not make jewellery and a necklace said to have been designed by him was presumably made after his death. Comparing his necklace with the drawing by Arthur Gaskin of his necklace Rose Lattice, (Plate 72) which was made in 1910, shows to what an extraordinary extent Gaskin, who was a keen admirer of his, was en rapport with Morris's ideas.

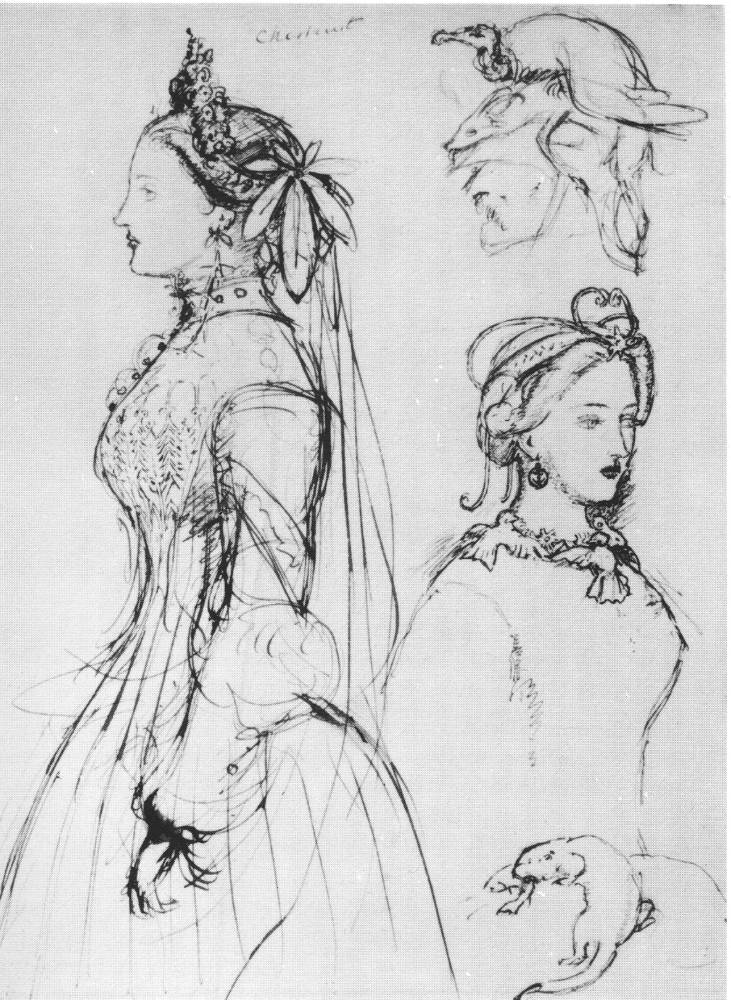

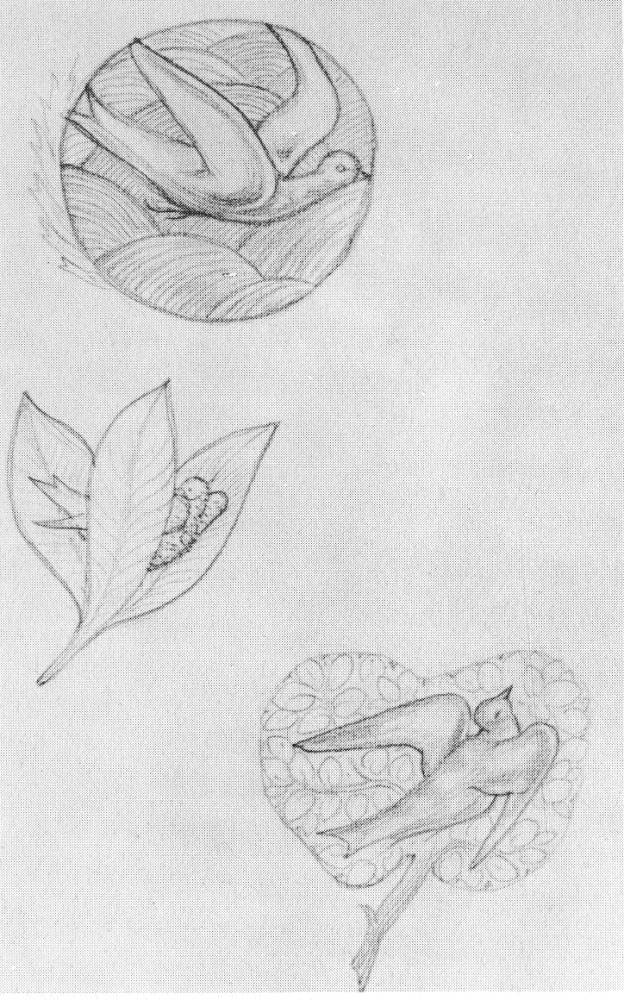

Left: Plate 74. Sketches of Natural Ornament. Sir John Everett Millais. 1853. Private collection. Right: Plate 79b. Three designs with bird motif. Designed by Sir Edward Burne-Jones. Courtesy of the British Museum.

Both Millais and Burne-Jones also made designs for jewellery. Millais' designs are for fantastic jewels rather like the ornaments in a picture by Gustave Moreau, though they derive directly from nature, and Moreau's jewels are inspired by old pictures and prints. Millais' two drawings entitled Sketches for Natural Ornament are of Ruskin's wife, Euphemia Gray, whom he married later, done at the time when Millais was preparing drawings to illustrate Ruskin's lecture on “The General Decoration of Domestic Buildings.” This lecture was given in Edinburgh in 1853 and its subject was the use of natural ornament in the decoration of architecture. These drawings show a remarkable foretaste of the shape of jewellery design at the end of the century. It has been remarked elsewhere that Millais' design for the tracery of a Gothic window which was done at Ruskin's instigation at the same time as the Sketches for Natural Ornament, bears a strong likeness to the Art Nouveau style of the turn of the century. This pre-vision of things to come is even more evident in the jewellery, and though the possibility of turning these designs into actual jewels must have seemed remote in the mid-nineteenth century, one only has to look at the achievements of the French art nouveau jewellers to see that, with some not very extensive modifications, this could have been done fifty years later. The helmet in Plate 74 shows an equal foresight, it is very like the armour designed by Burne-Jones for the Irving production of King Arthur which was put on in London in 1895. Millais' designs for jewellery also included two scarf-pins, for [149/152] himself and his brother, again based in the best Ruskinian tradition on natural forms, one a goose and one a wild duck, which were actually executed. These pins are mentioned in a description of an expedition to Hendon written by William Millais in 1853: 'My brother wore a large gold goose scarf-pin. He had designed a goose for himself and a wild duck for me, which were made by Messrs. Hunt and Roskell — exquisite work of Art.' Millais is wearing the gold goose in the pencil portrait drawn by Holman Hunt which is now in a private collection.

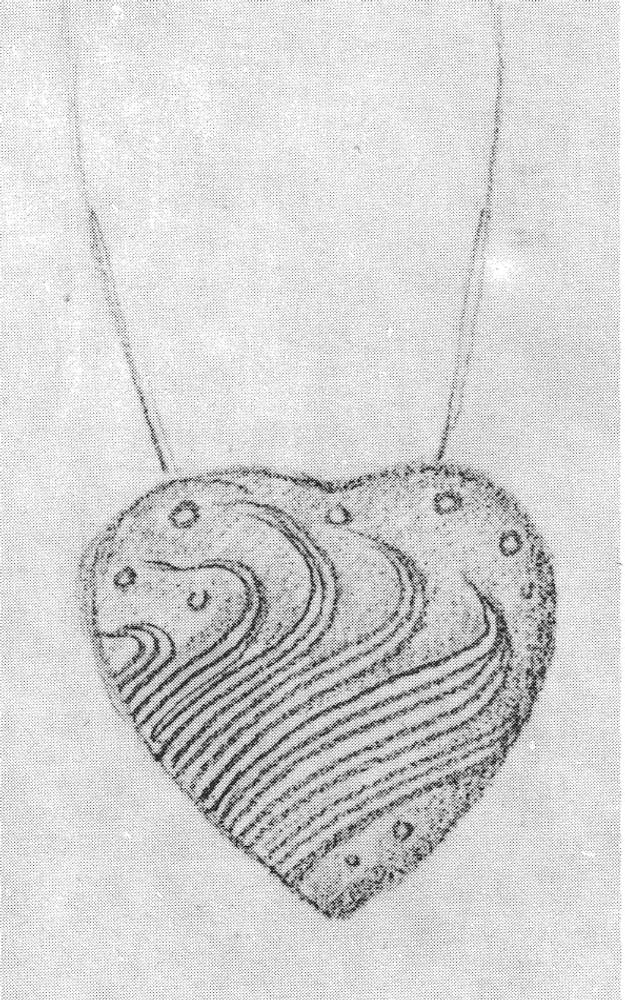

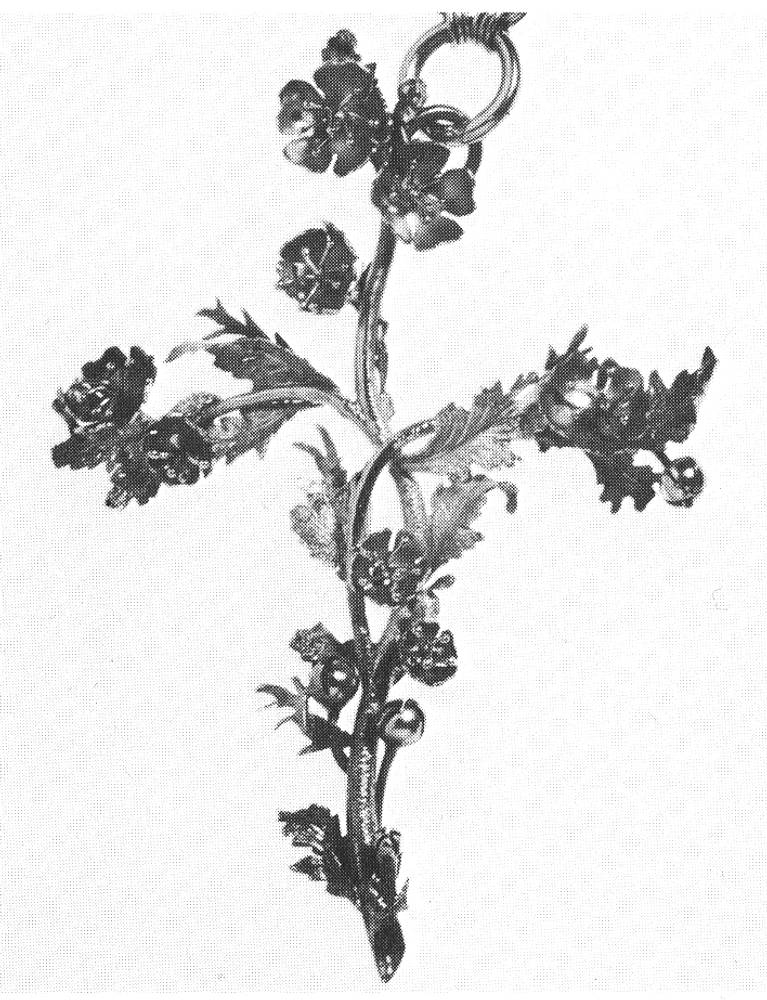

Jewellery designs by Burne-Jones. Left: Plate 79b. Brooch in enameled gold set with coral and turquoise. Private collection. Right: Plate 81. Design for heart-shaped locket or pendant. c. 1883-1897. Courtesy of the British Museum.

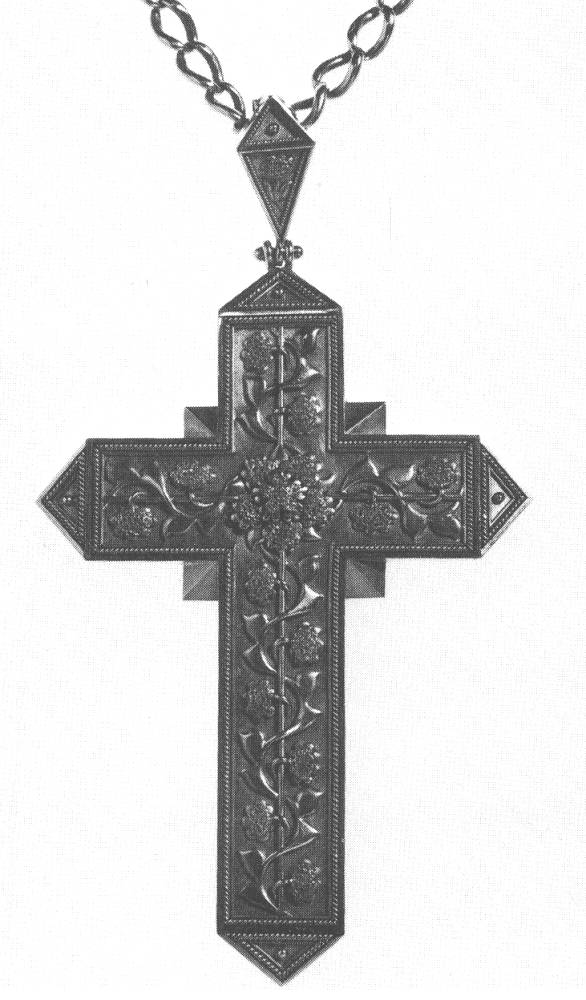

Burne-Jones's drawings are very different from the Natural [152/154] Ornament drawings, being designs for use by a jeweller, though they still require considerable intelligent interpretation to make them practicable for the intended materials. The jewellery which was actually made for Burne-Jones is thought to have been by Child of Kensington, a particularly suitable choice in that the firm was capable of providing excellent workmanship but is generally deficient in originality as to design. I am indebted to Miss Claire Mackail, Burne-Jones's grand-daughter, for this suggestion. Burne-Jones was for many years a customer of Child's and might well have had his own designs made up by them. The bird brooch mentioned below is not marked with Child's mark, an impressed mark of a flower like a marguerite, but this may not have been done in the case of special commissions. Again, as in the case of Millais' Natural Ornament drawings, it was Ruskin who inspired these designs; he turned Burne-Jones's attention to jewellery when he asked him to provide a design for the 'Whitelands' cross. In 1881 Ruskin conceived the idea of offering a gold cross to Whitelands College in Chelsea (as it then was) to be presented to the most popular girl of each year who was chosen by her fellow students as the May Queen. This offer was enthusiastically accepted by John Faunthorpe, the principle of the College, and plans for the ceremony went ahead at once. On April 6th 1881 Ruskin wrote the following letter to Faunthorpe:

'This one line of thanks is to you and the college, and to say that I've written today to the goldsmith in whom I have confidence about a little cross of gold, and white may blossom in enamel, for the Queen. I think it will be more proper for the kind of Collegiate queen she is to be, than a crown or fillet for her hair.

The plan for decorating the cross with may blossom of enamel seems to have been abandoned, possibly it proved both too complicated and too expensive. The design for this first cross was made by Arthur Severn, the husband of Ruskin's cousin and devoted companion, Joan Agnew, and this cross is illustrated in Ruskin's Collected Works. It is the same as the cross on the left on plate 76, which was presented to the May Queen in 1882.

Left: Plate 76. One of the Whitelands "Queen of May" crosses. The cross was designed by Arthur Severn and used in 1882. Right: Plate 78. Gold cross made by Hunt and Roskell and owned by John Ruskin.. Both reproduced courtesy of Whitelands College.

Both the date of this project and the form of the design chosen for the cross make it seem likely that this ceremony was conceived by Ruskin as some kind of memorial to Rose La Touche, the girl [154/155] whom he had hoped to make his wife. He had been profoundly affected by her death which took place at the end of May in 1875, which would explain the choice of the date for the ceremony and the May blossom which was to decorate the crosses. His words to Carlyle indicate that these flowers were connected in his mind with Rose La Touche's death, he was disgusted to see that the blossom on the cross was thornless, 'as if a true queen's crown could ever be without its thorn.' It would have seemed a fitting memorial to present this jewel to the most popular and, Ruskin hoped, the most beautiful girl in the College. In this last respect he was doomed to disappointment, after waiting with impatience for the photograph of the first May Queen to arrive, Ruskin was distressed to find that she was not very pretty. Her photograph may not have been very flattering and the poor girl suffered from the added disadvantage of being in mourning so that she could not [155/156] have worn the specially designed gown even had it been ready. As the Whitelands students left the College and went to teach in other parts of the country the May Queen ceremony was introduced into other establishments. Miss Martin, a former governess at Whitelands, persuaded Ruskin to institute a similar practice at the High School for Girls in Cork and for this festival a brooch decorated with wild roses was designed, '. . . he Ruskin gladly established a similar festival at Cork, the Queen in this case being for reasons that may be guessed a Rose Queen.'

As well as enlisting the help of Arthur Severn and Burne-Jones, Ruskin asked one of his protegees, Kate Greenaway, to design the gown, which was made up for successive Queens for some years in spite of the fact that he did not like it.

Arthur Severn's cross was used for two years, then in March 1883 Ruskin wrote to Burne-Jones asking him to make a design for the cross which was to be used that year. The following letter was written from Herne Hill on March 14th: [156/157]

'Darling Ned . . . Also I'm going to beg you most piteously to design for me the little hawthorn cross for next 1st May at Whitelands. This must be done soon to put in hand, if possible while I'm in town . . . The cross is always in pure gold and about this size [drawing in margin of a plain cross approx. 5 cms. high] and I've usually kept it to about ten guineas in price — but if you'll put some pretty work in it I don't care what it costs.'

Another letter followed which is printed in Memorials of Edward Burne-Jones by Georgiana Burne-Jones, Macmillan, 1906, p. 131, with Burne-Jones's reply:

'The Cross . . . may be any shape you like, but it must be hawthorne because it is for the 1st May, when they choose a May Queen at Whitelands, the girl they love best, and I give her the hawthorne cross, annually — and the whole lot of my books to give away to the girl she likes best.'

Burne-Jones replied:

'I am about the jewel now, and the design will quickly follow this letter. It doesn't please me a bit, because I design blindly [157/158] and I don't know how it will look. By, an early post to-morrow you shall positively have it though, with such written directions as I can give knowing nothing practically of the art. If anything strikes you as ugly in it, send it back and I will do it again.'

Further letters followed containing various designs for the cross, Burne-Jones claims that he made fifty, and none seem to have pleased him completely. The following are three previously unpublished letters from the F.J. Sharp Collection which is in the Library of Queen's College of the City University of New York. The letters come from The Grange, West Kensington, and arc undated but must have been written in March 1883 in the view ol Dr Helen Gill Viljoen of Queen's College who kindly brought these letters to my attention.

here are 2 or 3 schemes — tell me by return which I shall make working drawings for — & let the Goldsmith call on me & I'll explain all — I am not proud of them — I find it somehow hard to do, perhaps because I am so harassed with work. The 1st is the best isn't it? a flat thing with a little filigree arch on it — blossoms could be in silver with golden spikes.'

You don't know how hard I find that little cross to do — I think I have made fifty designs — but yesterday I chose 3 for you - & I want you to say which you like best so I'll send them first to you at Brantwood — crux est celare crucem. I don't know why I find it hard - perhaps because I'm a bit exhausted with work this spring — anyhow in a day or two you shall have what I have done, & I'll give that to Morris &: I'll rouse the dormant Hollyer;, and at once.' A sketch in pencil of a delicate cross with all four arms of equal length which is overlaid with a branch of May blossom, pendant from a knotted chain, is now enclosed with this letter.

' . . . I have made a new one — a little like enclosed'— send it to Ryder — I shall go tomorrow to instruct workmen —

| Cross to be ordinary gold | blossoms | silver | leaves | green gold | stem | red gold | thorns | copper gold |

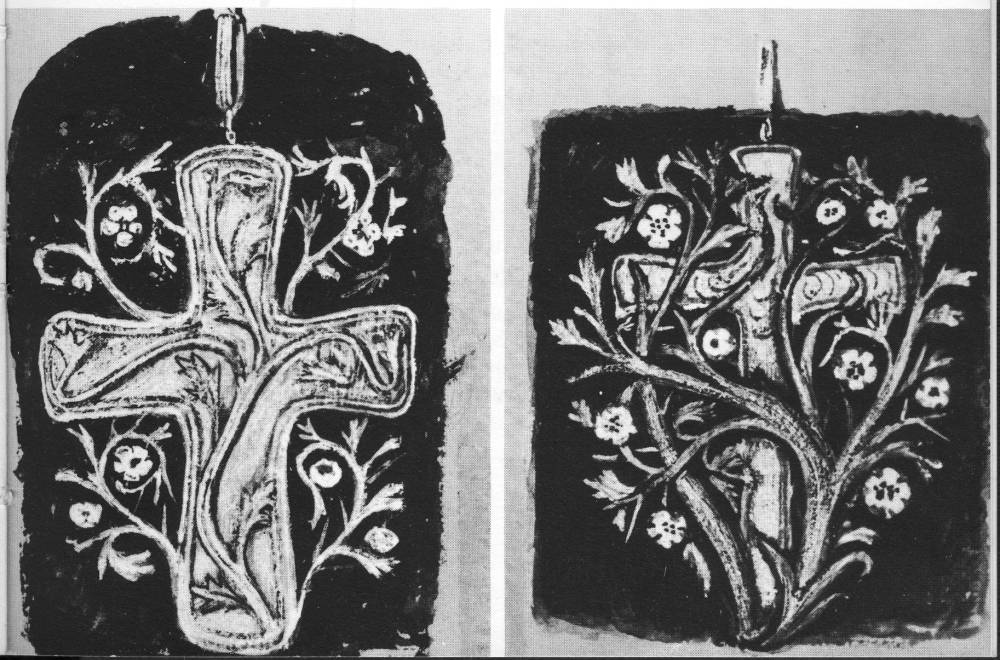

Now enclosed with this letter is a design for a cross of celtic type [158/159] interlaced with branches or May blossom on a black background, very like the two drawings on plate 77.

Plate 77. Two designs for the Whitelands' cross by Edward Burne-Jones. Courtesy of the F. J. Sharpe Collection, Queens College of the University of New York.

There is a tradition at Whitelands College that Burne-Jones's cross was decorated with enamel but nothing in the correspondence about the design supports this theory. Ruskin wrote to Burne-Jones on the 1st May 1883 to express his delight with the finished cross:

'The success of the Cross to-day is perfect — in all possible ways — and I cannot enough thank — nor enough congratulate — you — them — and my little self on all the matter. Ryder will have credit out of it, too, and lately all's well — AND ends well — or rather begins well — for there is no saying of how much this Whitelands cross, by your design, is the beginning.'

There is one more letter from Ruskin on the subject on the Whitelands Cross which throws some light on the mystery of why the Burne-Jones design was used only once. It does not say to whom this letter is addressed but it seems likely that it was to Joan Severn, as none of the letters to her have an opening, and because of the reference to 'Arfie', her husband Arthur Severn, who designed the first Cross. This letter was sent from Brantwood on 6lh January 1884:

I think the sooner the Whitelands cross is in hand now the better ... if Art ic would make another drawing to change the present form of the useless cross it would beat Jones's, which the Queen Regnant's father doesn't like — because its not hawthorny enough. [160/161]

Although the crosses were given unconditionally to the chosen Queens, some of them have found their way back to Whitelands College, but the cross designed by Burne-Jones is unfortunately not among their number. A large gold cross which belonged to Ruskin himself was given to the College. This cross was made by Hunt and Roskell but was presumably designed by Ruskin himself and it does have something in common with Burne-Jones's ideas for the Whitelands Cross. Ruskin never ceased to voice his deep contempt for modern jewellery and jewellers, a particular type of vulgarly ostentatious jewellery being associated in his mind with the Royal Jewellers, Rundell and Bridge; but Hunt and Roskell do not seem to rate quite so low in his estimation. Millais had the two [161/162] scarf pins he designed made up by this firm; he also urged Holman Hunt to go there for the ring which he gave him before Hunt's departure for Syria in 1853.

After the Whitelands commission, in spite of the fact that it had caused him such trouble, Burne-Jones continued to make designs for jewellery, many of which are in the Secret Book of Designs (now in the British Museum) and the sketchbook containing the Designs for a Flower Book which is in the Victoria and'Albert Museum. Georgiana Burne-Jones says in the Memorials

'Much later in life his thoughts turned voluntarily to jewel-work, but I only remember one thing which he carefully and completely designed and saw executed, a brooch, representing a dove, made of pink coral and [162/163] turquoise, surrounded bv olive-brnnches of green enamel.' (Plate 79b).

Curiously enough Lady Burne-Jones does not mention a ring in the form of a winged heart in peridot and chased gold which she wore continually, which was designed for her by her husband. It is possible that she did not regard this ring as being designed by Burne-Jones since the form of the jewel was probably worked out in consultation with the jeweller who made it and not first drawn by Burne-Jones himself.

Lady Burne-Jones speaks of these jewellery designs having been made 'much later' than the Whitelands Cross drawings, but enclosed with one of the letters to Ruskin about the cross are some drawings for jewellery which are not connected with the cross at all. These drawings of four different brooches or pendants, three oval and one circular, are more finished versions of some of the jewellery designs in the sketch-book in the Wightwick Manor collection. The drawings in the sketch-book arc accompanied by notes indicating the stones to be used for the jewels, and one brooch is called 'Byzantine'. In the catalogue of the Burne-Jones exhibition held at the Fulham Public Library in 1967 this sketch-book is provisionally dated 1865 because one of the drawings is a copy after an engraving by Durer of two dogs which was given to Burne-Jones in 1865.

It seems most unlikely that Burne-Jones made designs for jewellery before being approached by Ruskin in 1883, and both the Secret Book of Designs and the Designs for a Flower Book were begun in 1882 and added to at intervals during the next fifteen years. Lady Burne-Jones says that her husband made the last drawings in these books in 1897.

These designs for jewellery include a number of bird drawings (Plate 79a) some of which would clearly be most effective if carried out on enamel. A passion for enamelling swept through late nineteenth-century artistic society and a small enamelling kiln was set up in more than one pantry unused estate room. Among the talented amateurs who took up this absorbing hobby was Burne-Jones's friend and patron Mrs Percy Whyndham. It is tempting to imagine that some of these little drawings were translated into jewels in the enamelling kiln 'Clouds'.

Had Ruskin's ideal and the Pre-Raphaelite belief been pursued [163/164] more consistently in jewellery designs by the members of the Brotherhood and their associates, they would surely have been inspired by Botticelli and the early Renaissance Italians, while sticking faithfully to nature for the motifs, and the result would have been exactly like the 'Arts and Crafts' jewellery of the turn of the century. The Pre-Raphaelite designs, however, predict with considerable accuracy the shape of French Art Nouveau jewellery, hardly surprising since the poetic vision of Rossetti and Burne-Jones was more clearly understood and admired by the French, accustomed as they were to the magical, half mediaeval, half oriental world of Gustave Moreau (Plate 73; below) whose jewelled canvases had as great an effect on the jewellery of 1900. [164/165]

Plate 73. Detail from 'Les Licornes' by Gustave Moreau. Courtesy of Musée Gustave Moreau.

2 March 2015