fter a long period of neglect, lasting from the end of the first World War until barely ten years ago, the designers of the fin de siècle are now well served with an almost excessive number of books, exhibitions and magazine articles devoted to examining every aspect of their work. The development of the main artistic movements of the period has been exhaustively examined and the work of the artists connected with them carefully traced; it is apparent that jewellery design played an important part in the evolution of the style which is known, for convenience, as Art Nouveau.

By the end of the century the ideas put forward by William Morris and John Ruskin, already adopted by the Aesthetes, had gained wide acceptance with the general public, even to the extent of being exploited with some commercial success. The 'artistic' jewellery, which provides an interesting contrast to the conventional commercial product of the period, that is, the elaborate diamond jewellery which had been fashionable since the Second Empire and which continued to be worn during the last twenty years of the century and throughout the Edwardian period, was designed by artists working in the Art Nouveau style peculiar to the French, the Arts and Crafts or Celtic Revival style which was characteristic of most of the English work, and the other variations which evolved in Italy, Belgium, Austria and [165/167] exception of Philippe Wolfers whose designs are more like the French) had stronger links with C.F.A. Voysey (Plate 89), C.R. Ashbee (Plate 82 & 88a) and the Guild of Handicraft, and C.R. Mackintosh and the Glasgow School, than with Parisian Art Nouveau or the Ecole de Nancy.

Left: Plate 82. Peacock pendant. Designed by C. R. Ashbee; executed by the Guild of Handicraft. 1902. R Right: Plate 83. Peacock Brooch designed by L. Gautrait, French 1900. Gautrait was an engraver and designer for the Parisian firm, Gariot. Both reproduced courtesy of the Victoria & Albert Museum.

Since the production of much of the English jewellery was in the hands of individual artists with small workshops manned by devoted followers, the designs are mostly highly idiosyncratic and resist any rigid classification. The Arts and Crafts Society, founded in 1886, provided a 'shop window' for many of the Guild of Handicraft artists and the Glasgow, School artists as well as a number of individual experimental figures like Henry Wilson (Plate 85a & b), Arthur Gaskin (Plate 72, 87a & b) and Omar Ramsden and Alwyn Carr (Plate 88b).

Left: Plate 85a. Ship pendant by Henry Wilson. Courtesy of Hessiches Landes-museum, Darmstadt. Right: Plate 85b. Design for a ship pendant. by Henry Wilson. Much of Wilson's original design has been lost in the execution of the pendant and the delicate birds are hardly recognisable. Courtesy of the Victoria and Albert Museum.

The work of C.R. Ashbee and Mackintosh was to be the main inspiration for the Vienna Secession movement; the jewellery of Germany.

Plate 95. Two silver brooches made by Jensen of Copenhagen. Courtesy of John Jesse. The jewellery style established by Georg Jensen at the turn of the century was to serve as a basis for the firm's designs until the mid-twentieth century.

In spite of the steady erosion of regional distinctions which had been apparent since the eighteenth century, Art Nouveau design does show quite distinct national characteristics, French Art Nouveau being recognisably different from Belgian or Italian in spite of their common preoccupation with organic forms, used with such different effect by Henri van de Velde (Plate 99) and Hector Guimard (Plate 98). The Belgians (with the [167/168] Koloman Moser, Joseph Hoffman (Plate 97) and Otto Czeschka has much in common with theirs, as does the work of the Jugendstil designers in Germany.

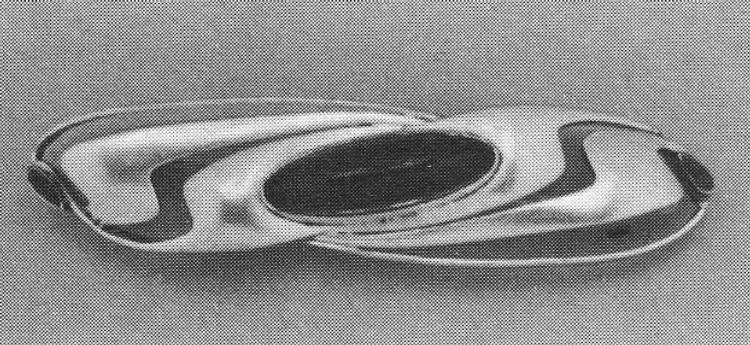

Plate 96. Left: Design for a buckle by Rex Silver, c.1902 for Liberty and Co. Reproduced courtesy of the Victorian & Albert Museum. Right: Belt Buckle by Réné Foy. Source: the 1899 Studio.

Plate 97.Buckle designed by Joseph Hoffmann, made by the Weiner Werkstatte, 1905, silver, partly gilt and semi-precious stones.

It is unusual to find jewellery design dominated by artists, rather than craftsmen who were either born into the trade or apprenticed at an early age, but this is symptomatic of the decorative art of the period. The creative energy which had produced the painting and sculpture of the mid-century was now focused on the minor arts such as pottery, glass, metalwork and jewellery. It turned out a mixed blessing but this is not the place to discuss the merits of vases which cannot hold flowers or glasses which cannot be drunk out of, and the question of whether jewellery is wearable or not really depends on what kind of a person you are. A number of talented sculptors, architects and painters turned to designing and sometimes to making jewellery, in some cases even entirely abandoning their former occupation. The list of European artists who made ewellery designs is formidable, as well as those already mentioned above, it includes Alfred Gilbert (Plate 62), Charles Ricketts (Plate 60a, 33a & b & 93) and George Frampton; Margaret Macdonald, wife of C.R. Mackintosh, her sister Frances Macnair, Talwin Morris and Jessie M. King, all connected with the Glasgow School; May Morris Plate 94; immediately below), Mr and Mrs Arthur Gaskin , Nelson and Edith Dawson, John Paul Cooper (example of his work) and H.G. Murphy, who all had a general artistic raining but turned to jewellery designing as their main occupation.

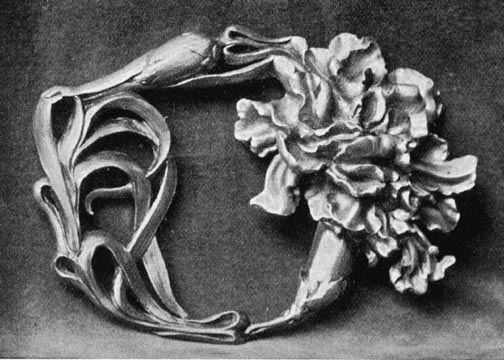

Plate 94. Diadem designed and made by May Morris. c. 1908. Courtesy of the National Museum of Wales, Cardiff.

In France, Alfonse Mucha, Eugene Grasset and the architect and furniture designer Edward Colonna did much the same. On the other hand, René Lalique, one of the most important figures in the development of the French Art Nouveau style, was a jeweller by training, and many of the other names connected with Art Nouveau jewellery design are already familiar from the Second Empire, Lucien, son of Alexis Falize; Georges Fouquet (Plate 110) he creator of the style known as Mille-neuf-cent, son of Alphonse Fouquet, and father of the well-known modern designer, Jean Fouquet; and Emile (Plate 101), son of Francois-Desiree' Froment Meurice. Philippe Wolfers, Louis Comfort Tiffany, Carl and Agathon Fabergé, and Paul and Henri Vever, author of La bijouterie Francaise au XIXe Siècle, succeeded to their family business.

Left: Plate 103 Brooch in enamelled gold and copper. Marcel Bing, 1900. Courtesy Musée des Arts Decoratifs. Version of a brooch made for, 'La Maison de l'Art Nouveau', the shop opened by Samuel Bing in 1895. Reproduced courtesy of la Musée des Arts Decoratifs. Right: Plate 104. The 'Princesse Lointaine' Brooch — a portrait head of Sarah Bemhardt in the role of Melisande. Designed by Alphonse Mucha and made by Alphonse Fouquet. Reproduced courtesy of Hessiches Landes-museum, Darmstadt.

The jewellery designed by Mucha, Grasset and Colonna was made by Fouquet or Vever, all of which seems to indicate a [168/169] greater professionalism in French 'artistic' jewellery than in the English, where creative originality and hand-craftsmanship were valued above professional finish, which gave great scope to the craftsman with a small workshop, and even adapted well to the abilities and limited technical knowledge of the semi-amateur.

Left: Plate 84a. Peacock design for a brooch or buckle. by Eugene Grasset, 1900. Courtesy Musée des Arts Decoratifs. Right: Plate 84b. Peacock Buckle designed by Eugene Grasset, made by Vever 1900. Courtesy of the Cooper-Hewitt Museum of Decorative Arts and Design, Smithsonian Institution.

French Art Nouveau jewellery is, without doubt, of unrivalled originality, both in design and in the use of unusual materials and combinations of media, particularly at this date in the rejection of diamonds and other precious stones as the determining factor in the value of the jewels; now the contribution of the artist must be assessed as well as the cost of the materials, which could be almost negligable. The jewellery of Lalique, his assistant Feuillatre who became one of the most accomplished enamellists of his period, Georges Fouquet, Alphonse Mucha, Marcel Bing and Eugene Grasset, is made with copper, horn, ivory, glass, paste, hard-stones and enamel as well as every kind of colour of semi-precious stone. Much of the French and Belgian jewellery, while not being primarily of diamonds, is set with a number of brilliant-cut or rose-cut stones, but these and almost all first quality precious stones are conspicuously absent from English Arts and Crafts [169/170] pieces of this date. Fabergé's hard-stone carvings of flowers and fruit and Philippe Wolfers' use of ivory from the Congo overlaid with metal inspired copyists long after the last traces of Art Nouveau had disappeared from jewellery design.

Left: Plate 86: Pendant 'I'an neuf enamelled gold and chrysoprase by Carl Fabergé, marked K.F. in Russian characters. Courtesy of Hessiches Landes-museum, Darmstadt. Superficially Fabergé's pendant is not unlike Wilson's, and in his choice of materials, stones of little intrinsic value and enamels, he was completely in sympathy with the Arts and Crafts jewellers, but his workmanship was always meticulously professional. Right: Plate 87a. Pendant and Chain silver, partly gilt, amethysts and an emerald designed and made by Arthur Gaskin 1910-1912. Private collection.

Plate 87b. Designs for Jewellery by Arthur Gaskin 1908-1912. Courtesy Victoria and Albert Museum.

René Lalique, rightly regarded as one of the key figures in Art Nouveau design, and certainly the most influential jeweller of his [170/171] period, was given a unique opportunity to develop his ideas without being worried by pettifogging financial considerations, which dogged many of the English designers, by the patronage first of Sarah Bcrnhardt, for whom he made two pieces of jewellery in c. 1893-1894, and then of Calouste Gulbenkian, for whom he iade the most remarkable series of jewels between 1895 [171/172] and 1912 which are now in the Gulbenkian Foundation in Lisbon. Much of Lalique's work, particularly some of the pieces for Gulbenkian, are hardly jewellery 'within the meaning of the act', being virtually unwearable, but were clearly conceived as works of art. The flowering of high Art Nouveau was predictably brief, reaching a peak of invention in 1900 at the time of the Centennial Exhibition in Paris and rapidly declining thereafter. Infinitely less spectacular in all its manifestations, English Art Nouveau, largely centred on the Guilds of Handicraft, Morris's textile workshops at Merton Abbey, and later Liberty's venture into silverwork and jewellery, was already established as a recognisable trend by the end of the eighties, and in the final analysis can be seen to have had a greater influence on twentieth century design. Latter day interpretations of Lalique or Emil Galle are obviously derivative, whereas the experiments of Alfred Gilbert, Mackintosh, Ashbee, Henry Wilson and their followers have obvious affinities with the decorative design of the present day.

Left: Plate 88a. Waterlily pendant and chain. gold, silver, enamel and pearls by C.R. Ashbee c. 1900. Courtesy of Hessiches Landes-museum, Darmstadt. Right: Plate 88b. Pendant and chain, gold, silver and enamel by Omar Ramsden and Alwyn Carr 1908-1912. Courtesy the Purple Shop.

In 1888 Alfred Gilbert designed his famous Preston Chain, made for the Mayor and Corporation of Preston, widely regarded as a proto-type Art Nouveau piece, although Gilbert despised the movement and insisted that he was entirely dissociated from it. Jewellery designed by him (see Plate 62) has also been described as 'mannerist', which he might have approved.

The Guild of Handicraft, founded by C.R. Ashbee in the same year, provided a starting point for the development of a considerable, though not very profitable, trade in handcrafted jewellery. Ashbee's designs, like the 'Peacock' pendant, made by the Guild of Handicraft in 1902, a version of a design which Ashbee used more than once, and the pendant and chain now in Darmstadt, inspired much of the work of the Arts and Crafts designers; his influence extended further afield to Vienna where he exhibited by invitation with the Secession artists in the VIII th show in the autumn of 1900, again in the XVth show in 1902, when jewellery by Edgar Simpson, one of his closest imitators, was also shown, in the XVIIth show, and in the XXIVth show in 1906.

Plate 90.Designs for jewellery by Edgar Simpson c. 1899-1900. Edgar Simpson borrowed freely from the ideas of Ashbee and the Guild of Handicraft. Courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Before the turn of the century activity in this branch of jewellery design had become extensive. In about 1895 Henry Wilson had abandoned architecture to set up a workshop for the production of metalwork and jewellery. His finest work, which has a [172/174] positively Byzantine richness, is an intricate combination of cobweb-like gold work combined with, or laid over, coloured enamels used in a variety of techniques, painted enamel, cloisonné, pliqué a jour and applied enamel decoration on mounts and surrounds.

The development of complex and demanding enamelling techniques was a feature of all styles of Art Nouveau jewellery design. The em>pliqué à jour enamel found in much of the French work of the period was elaborated by Comte du Suau de la Croix to produce the effect of uncut or cabochon stones, by using translucent enamel in an openwork setting that was built up in [174/175] high relief. English craftsmen, though prepared to use both pliqué à jour and cloisonné to create certain effects were more drawn to painted enamels which were used to decorate all kinds of metalwork pieces, and jewellery relying wholly on enamel for its decoration with few, or even no, stones used in the setting became popular with aesthetic patrons.

Left: Buckle in translucent enamel on silver. 1902. Right: Good Tidings. c. 1901. [Neither image in print edition.]

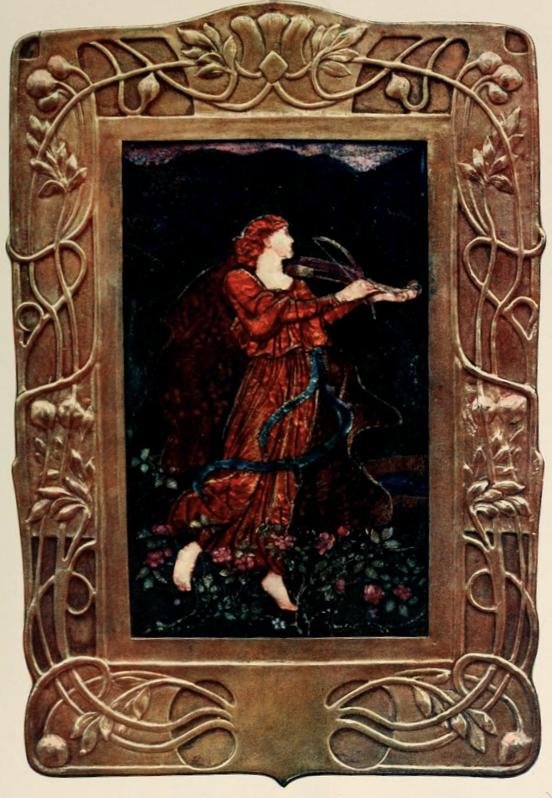

Alexander Fisher, who had gone to Paris in 1884 to study enamelling and set up a studio in London soon after his return, began making painted enamels with a subtle range of colour and texture hitherto unknown in enamel miniature painting, which were used to make pieces of jewellery. His famous girdle of painted enamel plaques, made between 1893 and 1896, 34 inches long 3 1/2 inches deep with a buckle over 4 inches high, each plaque decorated with scenes from Wagnerian operas, is now in the Victoria and Albert Museum. It was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1895 while still unfinished and at the Arts and Crafts Exhibition a year later. It was in this same year (1896) that Hubert von Herkomer, the painter, became interested in enamelling and began the experiments with firing techniques that were to increase the range of possible tones and effects still further. In 1897 he produced a badge for the Royal Society of Painters in Watercolours which is very Fisher-like in colour and technique, and the remarkable 'Herkomer Shield', which was made in 1907, must be one of the largest enamelling projects ever carried out.

Left: A Suite of Necklace, Brooch, and Earrings by Arthur and Georgie Gaskin. Right: Nelson and Edith Dawson by Nelson and Edith Dawson. Both images reproduced courtesy of the Fine Art Society. Neither image in print edition.

Nelson Dawson, who, with his wife Edith (m.1893), set up a workshop for the production of handmade silverwork and jewellery on the same lines as Henry Wilson and Mr and Mrs Arthur Gaskin , was a pupil of Alexander Fisher from about 1891. He taught his wife enamelling and she carried out most of the enamelled decoration of the jewellery and silverwork, a task which was to lead, in both her case and the case of Mrs Gaskin, to collapse through over-work. The fumes from the enamelling kiln were highly detrimental to the health, and the financial basis of these jewellery ventures always so extremely insecure that the pressure of work was far too great.

The Morris workshops survived because they were patronised by the rich, a fact which was a source of great dissatisfaction to the socialistic Morris; Liberty's metalwork venture succeeded because the designs were rationalised to allow a certain amount of mass-production, with [175/176] only a final touch of hand-finishing to conform with the fashionable adulation of hand-work. The most fortunate jewellery designers were of course those whose inspiration was not subject to the limitations imposed by these sordid financial expedients, like Charles Ricketts, whose jewellery was designed and made for friends. George Frampton, the sculptor, who had become interested in metalwork some years previously, started enamelling in about 1897 and made some pieces of enamel jewellery for his wife in 1898, as he claimed that it was impossible to find 'artistically effective ornaments' for her. This jewellery just pre-dates both the Gaskins' first venture into jewellery-making and the Liberty 'Cymric' venture by one year; although the ten years after the turn of the century were to prove the most exciting and prolific in work that Frampton would presumably have allowed to [176/177] be very 'artistically effective', even by the last five years of the nineteenth century a considerable amount of jewellery of this sort had been made and exhibited. The Arts and Crafts Exhibition in 1896 had jewellery by Ashbee and the Guild of Handicraft, enamels by Alexander Fisher and silver work and jewellery by Henry Wilson. All the pre-1900 volumes of the Studio (up to vol.XX) are full of examples of the work of these and other experimental craftsmen. The Studio Special Number of 1902, Modern Design in Jewellery and Fans , sums up the achievements immediately proceeding and during the last year of the century, which had seen the mounting of the great Centennial Exhibition in Paris where the whole range of high Art Nouveau jewellery was laid out before the astonished and frequently disgusted gaze of the general public.

Inevitably, between the end of the first World War and the present day much of this jewellery was consigned to the melting pot. As very lew of the English pieces contained worthwhile precious stones there was no reason to keep them; at that time it seemed inconceivable that anyone should ever again feel any interest in them. Until ten years ago Art Nouveau in all its manifestations was considered perfectly hideous. Perhaps it would [177/179] not have suffered such a total aesthetic eclipse had it retained its early reputation for decadence and depravity; much of the jewellery that survived w^is kept for sentimental reasons, or through sheer inertia, but a sufficiently large quantity did survive, including some predictably second-rate pieces, and it is now avidly collected like all the rest of the jewellery of the nineteenth century.

The last two decades of the nineteenth century are only technically Victorian, the shadowy figure of the widowed Queen having long since yielded leadership of the social scene to the Prince of Wales and his proverbially elegant wife; both the social and the artistic scene had begun to throw off the values and restrictions of mid-Victorian thought long before 1901 and culturally speaking the Edwardian period could be said to begin in the eighties. Though the tendency to wear little or no jewellery during the day, which had previously been apparent in the fifties, had increased since the fall of the Second Empire and the emergence of the severely tailored 'New Woman', a great profusion of diamonds were still fashionable with evening dress, and continued to be so until the outbreak of the war in 1914. [179/180] Following the example oi the Princess of Wales, later Queen Alexandra, the upper part of the dress would be covered with a variety of diamond stars, crescents, bows and flowers, the elegant but rather trivial jewellery which was the staple product of the trade and embedded in the elaborately arranged hair would be further stars and crescents as well as ornaments in the form of insects which had lately become the rage. Not for nothing has the second half of the nineteenth century been called 'the age of the diamond'; it seems as if invention and innovaiion were abandoned in favour of virtual mass-production of precious trifles, but certain changes were taking place even in objects of apparently unassailable popularity. For the first time in at least sixty years the cameo went right out of fashion, to be replaced by the medallion. A revival of the art of the medalist had taken place in France and the eighties saw the production of a number of editions of these artistic medals, as opposed to commemorative medals, some of which were mounted like jewels. The massive gold jewellery and the Archeological and Renaissance designs which were fashionable in the seventies continued to be worn well into the eighties and nineties but by the turn of the century hardly any trace remains of the High Victorian style in jewellery design.

The foundations of the Art Nouveau style and the Celtic Revival on which the design of much of English Arts and Crafts jewellery is based, were laid in the fifties and sixties. The mid-Victorian preoccupation with organic or natural forms as a basis for decorative design was, in these last years of the century, to bear startling fruit.

Left: Plate 98. Models for Jewellery, a hatpin ornament and a ring, in gilded bronze and paste. designed by Hector Guimard for his wife, c. 1900. Museum of Modern Art, New York. Right: Tortoise-shell and Pearl Comb. Unknown designer. Source: the 1899 Studio. Right-hand image not in print edition.

Some of the most exotic work of the French Art Nouveau jewellery designers like Lalique and Fouquet, was based on flower and leaf forms, as was the work of Hector Guimard, whose influence, like that of Alfonse Mucha, was incalculable, because their work so insistently obtruded on to the consciousness of the public, the poster hoardings and the entrances to the underground system providing an unofficial art gallery alongside the great official exercise of the Centennial Exhibition in which some of the most ambitious Art Nouveau work was shown.

Left: Plate 99. Brooch in gold set with a tourmaline by Henri van de Velde. Made for the Maison Moderne in Paris in 1899. Courtesy of John Jesse. Illustrated in L'Art Decoratif Winter 1899-1900 p. 10. Right: Pendant. Unknown designer. Private collection. Not in print edition.

Both Mucha and Guimard only occasionally turned their attention to jewellery design. Mucha's work in this medium is perhaps the more successful since he was primarily a decorative artist like Grasset and understood the limitations of [180/181] decorative art as well as its possibilities, but it was not his jewellery itself that had the greatest effect on the great mass of imitative Art Nouveau jewellery that was made in the early years of this century, but the famous posters for Sarah Bernhardt; his two most stunningly original and effective pieces of jewellery were made for Bernhardt, the 'Princess Lointaine' brooch, Plate 104, and the snake hand ornament and bracelet made after the 'Mcdee' poster. The flower designs and idealised female heads from Documents Decoratifs (1902) were also widely copied. The actual jewellery designs in Documents Decoratifs, possibly through a somewhat defeatist attitude on Mucha's part to the capabilities of the type of manufacturing jeweller who would use such pattern book designs, are rather disappointing. The connection between the flowers and leaves of 1900 and the metalwork of the mid-century is not far to seek, the resemblance between the decoration of some of the silver in the 1851 Exhibition and Art Nouveau design is quite startling, a>nd what one might call 'free form' silver of this sort dates from as early as the late twenties, but the similarity rests almost entirely in the use of flowers which were to become the hallmark of 1900 decoration like lilies and waterlilies. Mid-century jewellery rarely shows any such previsionary tendency; the differences between the peacock by Baugrand, made for the 1867 Exhibition (Plate 32b) and the [181/182] peacocks by Gautrait (Plate 83), Grasset (Plate 84a & b) and Ashbee (Plate 83) are very obvious. The Natural Ornament designs by Millais (Plate 74) show a far greater affinity with the later work, and it seems highly unlikely that the Art Nouveau style could possibly have developed out of the work produced by the successful mid-Victorian commercial jewellers. The artistic influence of the Pre-Raphaelites, William Morris, Burges and Godwin, and the critical influence of the Goncourt brothers, Ruskin and, on a more superficial level, Oscar Wilde, were essential.

Apart from the extensive influence of William Morris, whose decorating firm had been in existence since 1861, the designers of the fin de siècle inherited from the Aesthetic designers of the seventies and eighties the mediaevalism of the Pre-Raphaelite painters and Viollet-le-Duc and the Japanese style of Braquemonde, E.W. Godwin and Christopher Dresser, both of which had by now undergone a fairly considerable process of rationalisation; many of the sources of the distinctive decorative idiom of the nineties can be traced to the work of these artists,. but the most important single source was the importation of Oriental art objects which were being extensively collected in France and England by the end of the sixties.

Japan had been closed to European trade since the seventeenth century, and except for a small number of objects which were released through the Dutch who had managed to maintain limited trading rights in Nagasaki, Japanese art was quite unknown in Europe until 1854 when a number of Japanese objects were shown at an exhibition held at the Old Watercolour Society in Pall Mall East. In 1858, after five years of negociations, the British and Americans managed to wrest trading rights from the reluctant Japanese. The Japanese then accepted an invitation to exhibit goods and works of art at the International Exhibition in London in 1862, and some of the pieces shown then found their way into Messrs. Farmer and Rogers Oriental Warehouse, the shop where Arthur Lasenby Liberty was employed from 1863 until it closed down in 1875, when he opened his own shop in Regent Street.

Before the International Exhibition in 1862 and even before the negociations for the Commercial Treaty had been completed in 1858, certain Japanese objects had found their way into the hands of artists and collectors, among them E.W. Godwin, William Burges, [182/184] Whistler and Felix Braquemonde. The prints in particular had the most profound effect on these men and were early recognised as an important discovery. Charles Lock Eastlake, the architect, in Hints on Household Taste, which was published in 1867, wrote:

' — I cannot help thinking how much we might learn from those nations whose art it has long been our custom to despise — from the half-civilised craftsmen of Japan, and the rude barbarians of Feejee.

Needless to say this vision of barbaric native workmen was soon dispelled by the obvious sophistication of the Japanese work. Both English designers like Godwin and Dresser, and the French had been quick to assimilate the newly discovered forms; Braquemonde, who was reputed to have four Japanese prints being used [184/185] as wrapping papers for a piece of porcelain in 1856 and to have been immediately fascinated by their colours and composition, showed his famous service japonais at the Paris Exhibition in 1867, where it created a considerable sensation. This dinner service was described by Philippe Burty, the biographer of F.-D. Froment-Meurice in the Gazette des Beaux Arts in 1869. He had published, in 1868, Les Emaux Cloisonnés ancien et moderne, in which he had noted that French artists were already using Japanese motifs in their work. Burty was a noted amateur of oriental art objects and he owned an extensive collection of Japanese ceramics and ivories. He must have come into contact with Emile Froment-Meurice, who had succeeded his father, while working on the book, F.-D. Froment-Meurice, Argentier de la Ville de Paris, which was published in 1883, and he might have been expected to have infected him with an enthusiasm for Japanese art; but Emile Froment-Meurice, remained faithful to the Renaissance inspiration of the mid-century designers, notably that of his own father, throughout the eighties and nineties, and only began working in a modified Art Nouveau idiom by the turn of the century (Plate 101), and his work still shows traces of neo-Renaissance composition even at this date.

Left: Plate 100. Design for a pendant French. c. 1880. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Right: Plate 101. Pendant in gold and enamel by Emile Froment-Meurice, 1900. This pendant is in the tradition of the romantic neo-Renaissance style, with slight concessions to contemporary taste in the female figure with long flowing hair. Courtesy of the Victoria & Albert Museum.

Left: Plate 102. Brooch in gold, diamonds and sard. c. 1880. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Right: Tie-pin with the head of a woman. Private collection. Not in print version

Lucien Falize on the other hand, whose father had produced some of the most elaborate second Empire jewellery designs (Plate 31), was profoundly affected by Japanese enamel designs, and produced cloisonné enamel-decorated pendants in a completely Japanese style; he had been to London in 1862 and had visited the International Exhibition where he saw the Japanese contribution, and he planned to visit Japan in order to study cloisonné enamelling as practised by the Japanese. Lucien Gaillard whose designs are less obviously Japanese in inspiration than those of Lucien Falize, actually employed Japanese craftsmen in his workshop. The Japonaiserie decorative motifs were taken from all kinds of Japanese art objects, textiles, ceramics, laquer on furniture, boxes, and particularly inro and the inlaid metalwork decoration like that found on the tsuba (or sword-guard) which in the early period of the Japanese mania were copied with very little alteration, but later became considerably modified as they were assimilated into the Art Nouveau style.

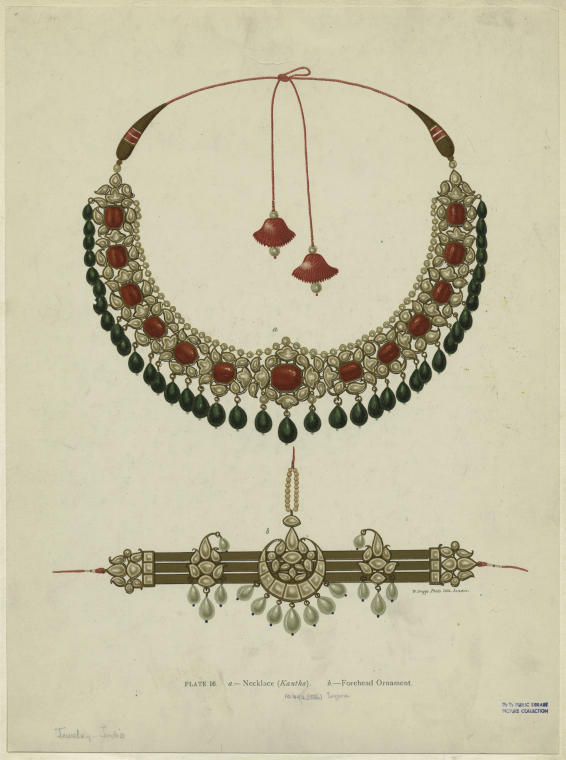

Although the influence of the newly discovered Japanese art [185/186] was considerable, it was not the only eastern style used to revitalise jewellery design in the last years of the century. Chinese jewellery, and to a much greater extent Indian jewellery, had been accumulating in this country for many years, collected largely for its curiosity value, but the Aesthetic Movement had made the curiosities fashionable, and when Queen Victoria was made Empress of India in 1876 Indian jewellery became fashionable in circles beyond the bohemian and artistic world of the Aesthetes. To judge from the very large number of pieces of Indian nineteenth-century jewellery which are to be found in the antique jewellery shops in this country nowadays, a considerable trade in Indian gem-set jewellery, filigree, and Moghul jade jewellery must [186/187] have been organised apart from the sporadic importations of returning travellers and officials. There is no record that the East India Company organised any regular trade in jewellery and it was, in any case, wound up long before Indian jewellery became fashionable. The Company's exhibit from the Great Exhibition in 1851 was presented to the Queen (see p. 64) and became part of the Crown Jewels. There were, of course, English goldsmiths and jewellery firms in India, like Hamilton's in Calcutta, as well as a branch of Garrards, but they were largely occupied with the aesthetically destructive task of teaching the Indian workmen to copy currently fashionable European jewellery of the most meretricious sort, an exercise which most certainly did not achieve the happy results of the cross-fertilisation of the fabric designs in the seventeenth century. Liberty's imported jewellery as well as textiles from India, some of which was mounted in this country and which bears the Liberty mark.

Left: Necklace (Kantha) and Forehead ornament from Jeypore enamels (1886). Courtesy of the New York Public Library; Right: Diamond Necklace for a Prince (kanthi). The necklace was shown in the Metropolitan Museum of Art's Treasures from India: Jewels from the Al-Thani Collection, October 28, 2014–January 25, 2015. Image: © Servette Overseas Limited 2013. All rights reserved. Neither in print version.

Indian jewellery of great magnificence was shown at the various International Exhibitions in London and Paris, for instance, the East India Company exhibit in 1851, Moghul gem encrusted jewellery exhibited in Paris in 1867, gold and enamel jewellery in the International Exhibition in 1872, and the Indian jewellery presented to the Prince of Wales which was shown in the Industrial Arts of India Exhibition at South Kensington in 1884. The influence of the Indian style is particularly apparent in French and English jewellery of the late nineteenth century (Plate 12c).

In spite of the collapse of the Imperial regime in Paris in 1870 and with it the extravagant social life of the court of Napoleon [187/188] and Eugenie which inevitably endangered the continued prosperity of such suppliers of fashionable objets de luxe as goldsmiths and jewellers, the taste for lavish diamond jewellery which had characterised the wealthy socialities of the sixties was, fortunately for Boucheron et al., found to be shared by the ladies of the Troisieme Republique, and by the American millionaire visitors to Europe who were to become an increasingly important source of business to the jewellery trade in London and Paris, as one after another the reigning houses of Europe collapsed. This taste for diamonds persisted until the supply of South African diamonds was temporarily cut off by the Boer War when coloured stones were once again, from sheer necessity, back in favour; it was not the garnets and amethysts of mid-century jewellery which were now popular, but the paler peridots, aquamarines, opals, pearls and moonstones. Diamond jewellery, and jewellery made of a mixture of diamonds and these newly fashionable pale stones was never supplanted in the world of fashion by the comparatively short-lived mania for Art Nouveau, continuing to be worn by most women throughout the Edwardian period. The profusion of South African diamonds, many of considerable size, had made this demand easy to satisfy, and firms like Massim the designer of some of the most popular flower spray jewels of the fifties and sixties, Boucheron and Vever were occupied with the production of more and more accurately observed flowers and fruit; and imitations in gold and diamonds of lace such as point-de-venise and guipun' which was advertised at 12,000-15,000 francs the metre, and intended for trimming dresses. In fact this lace was more usually bought in lengths sufficient for a bracelet or a length to be made into a bow, there being some limit to the extravagance of even the most ebullient American millionaires, now the most valued customers of the Paris luxury trade. A certain Mr Reed, Tiffany's agent in Paris, bought largely from Boucheron in the seventies, and the firm's jewellery became even more popular in America after Boucheron had exhibited in Philadelphia in 1875.

Left: Plate 91. Dragonfly corsage ornament by René Lalique. 1900. Courtesy Fundacao Calouste Gulbenkian, Lisbon. Exhibited in Paris in 1900 and Turin in 1902. Right: Plate 92 Dragonfly brooch in diamonds and enamel. c. 1900-1910. Courtesy N. Bloom and Sons.[Click on images to enlarge them.]

Lalique began his career designing small pieces of diamond jewellery in this style, designs of the utmost banality, and in most cases very much less good than the prototype; sub-Massim rose sprays, rather coarse lace bows and terrible little acrobats and windmills with turning sails which have none of the miniature charm of the Swiss [188/189] automata of the same type.

Left: La Source Pendant and Necklace. c. 1902. Ivory, enamels, opals, gold. Right: Brooch with Nude. Both images reproduced courtesy of the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore.

In view of these early efforts it is astonishing that he was later to produce the marvellous jewels which were shown by him at the Centennial Exhibition in Paris in 1900. Some of the best of the more conventional designers who ventured into the Art Nouveau style suffer from Lalique's lack of inspiration in reverse; their work in this idiom being mostly cautious imitations of Lalique's designs, like the timid Maison Boucheron Art Nouveau designs.

Brooch of Leaves and Berries designed by René Lalique. c. 1903. Gold, glass, enamel, citrine. Reproduced courtesy of the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore.

Hippolyte Teterger, whose Renaissance chatelaine in diamonds (Plate 65) made towards the end of the century is an impressive example of this type of work, exhibited an Art Nouveau style bracelet in the Centennial Exhibition (in 1900) which is much less successful. The design for a pendant in the drawing reproduced on plate 100 show how the female figures which are the sine qua non of a certain type of Art Nouveau design could be incorporated into modified Renaissance-style shapes (the grotesque mask has been retained in this design) to produce jewels which are the obvious predecessors of jewellery being made by Lalique, Vever and Henri Dubret, in about 1900. This drawing, now in the Metropolitan Museum, where it is catalogued as French, c. 1890-1910, resembles most closely the work of Louis Rault or Jules Brateau, who were both designing for the Maison Boucheron in the late seventies.

Apart from the influence of Japanese art and the use of Renaissance shapes and methods (Cellini's notebooks, which had already been used by Fortunate Pio Castellani, were extensively studied and his techniques adopted, particularly enamelling methods like pliqué a jour, by both French and English designers), the legacy of mediaevalism from William Morris and the PreRaphaelites was still of considerable importance to the designers of the turn of the century, particularly from the theoretical point of view. The teaching of Morris and Ruskin exerted a strong influence on methods and materials used in the manufacture of jewellery. The Arts and Crafts or Celtic Revival craftsmen in England in spurning the use of diamonds or other spectacular precious stones continued the tradition of artistic distaste for the type of jewellery that Boucheron purveyed, so profitably, to the Americans. In the face of such an unchanging preference for this kind of valuable jewellery, which all the most original designers of the nineteenth century had set out to change since the early years [189/190] of the Gothic Revival, it is amazing how great an effect the innovators did ultimately have on jewellery design. Even at the turn of the century the design of diamond jewellery still showed an early-Victorian tendency to resist change, and it remained for the Cartier designs of the nineteen-twenties with their uncompromisingly square lines and extensive use of the difficult baton, step and emerald cuts, to make the real break-through for this kind of jewellery.

The mixture of Gothic and Japanese which designers of this [190/191] period were almost bound to imbibe during a training in Paris or London during the sixties and seventies can be seen in the work of Eugene Grasset, who had studied with Viollet-le-Duc and had also become fascinated with Japanese art. His cover for the Histoire Des Quatre Fils Aymon, which appeared in 1883, is a rather Morris-like mediaeval illustration overlaid with bands of decoration of Japanese inspiration, a not unsuccessful combination, but Grasset did not pursue the possibilities of this mixture in his jewellery designs, which are based mainly on natural forms, [191/192] such as flowers, birds and fish, and the plates for his pattern book, which began appearing in monthly parts in 1896, La Plante et ses Applications Ornamentales, are completely in the Art Nouveau idiom. His jewellery designs are some of the most strange of all the many highly original ideas produced at the turn of the century, it is difficult to imagine quite who wore them and on what occasion, one experiences a similar difficulty with the more intractable of Lalique's designs. Many pieces of French Art Nouveau jewellery were objets de vertue on the same lines as Fabergé's little pots of flowers, or animals or Easter eggs. The weight of some of these pieces is a considerable disadvantage, apart from the extensive use of pliqué a jour enamel, an obviously impractical technique since it is only completely effective when held to the light, and the effect is inevitably lost when the jewel is worn. English jewellery design of the same period is with few exceptions more practical and wearable, and if by being more modest it sacrifices the dramatic quality of the French, this may explain the greater lasting power of the English artistic revival in the decorative arts. Some of the best English Art Nouveau work was done in the first decade of the present century, some even up to five or six years later, when the French experimental impulse which had produced the true Art Nouveau style was almost extinct.

No convenient break in the thread of late nineteenth century inspiration occurs just at 1901. The death of Queen Victoria is not marked by a recognisable finale to the Victorian design tradition; this had already faded away, bit by bit, during the preceeding ten or fifteen years, and between 1888 and the turn of the century the foundations of twentieth century modernism were laid. Some of the pieces of jewellery reproduced in this chapter were made eight of ten years after the death of the Queen, they are in no sense 'Victorian' pieces, but in a reign spanning sixty-four years many styles will be evolved. The 'High Victorian' style, on which many people are bound to base their judgement of the Victorian period, began to develop at the time of the Great Exhibition in 1851 and was overshadowed by the Aesthetic movement and the Handicraft revival in the eighties; to concentrate on this period excludes from consideration the early Victorian work as well as the post-1890 work reproduced in this chapter. To give a reasonably complete picture of the whole period it is necessary to include at least a [192/193] brief discussion of this generation of designers, most of whom were born in the sixties and were therefore bound to do much of their most important work in the twentieth century. [193/194]

Phoenix brooch in peridot with pliqué a jour enamel an gold.

4 March 2015