[The Fine Art Society, London, has most generously given its permission to use information, images, and text from its catalogues in the Victorian Web. This generosity has led to the creation of hundreds and hundreds of the site's most valuable documents on painting, drawing, sculpture, furniture, textiles, ceramics, glass, metalwork, and the people who created them. The copyright on text and images from their catalogues remains, of course, with the Fine Art Society. GPL]

t is a measure of William Morris's remarkable achievement that his name, indissolubly linked with the well known products of his firm has never been forgotten, unlike those of so many of his contemporaries. Interest

in his work, and that of the remarkable artistic talents

who collaborated with him in designing for Morris and

Co., has probably never been so great as in the last ten

years [i.e., the 1970s].

t is a measure of William Morris's remarkable achievement that his name, indissolubly linked with the well known products of his firm has never been forgotten, unlike those of so many of his contemporaries. Interest

in his work, and that of the remarkable artistic talents

who collaborated with him in designing for Morris and

Co., has probably never been so great as in the last ten

years [i.e., the 1970s].

Sideboard by George Jack. Click on thumbnail for larger image.

In considering the Firm's products in relation to the pioneering design of men like Jekyll and Godwin, the influence of Morris and Company seems to be out of all proportion to the small number of different objects they produced or to the originality of their designs in all the products except for the textiles and wall-papers. From the very start of his exhibiting career Morris was seen, not without justification, as a careful mediaevalising designer. The criticisms of his style which appeared in The Athenaeum (September 27th 1862), at the time of the International Exhibition in London: "It is to be regretted that Messrs. Morris, Marshall & Faulkner, who unquestionably are successful in applying Art-principles to furniture design, restrict themselves so devotedly to Gothic forms and character", were echoed a quarter of a century later when the firm's work was shown at the Jubilee Exhibition in Manchester in 1887. While it is possible to see the 1862 "King Rene's Honeymoon" cabinet, with its painted panels by Madox Brown, Rossetti, Burne-Jones and Morris himself, and the related desk (cat. no. 3) also designed by J. P. Seddon and also shown in the Gothic Court [at the Great Exhibition of 1851], as High Victorian neo-Gothic pieces in the Pugin-Burges manner, the massive sideboard designed by George Jack (cat. no. 18; not illus.) is a slightly modified version of this elaborate piece) which was the centre-piece of the Firm's 1887 stand in Manchester has an almost uncanny affinity with Mackmurdo's designs for the Century Guild stand, which provided a startling aspect of the Exhibition and which are now seen as the starring point uf the Modern Movement.

Two Handwoven Hammersmith Carpets by William Morris and Co.. Click on thumbnails for larger images.

Technically much of the early furniture was of the most uneven quality, ignorance of the basic principles of construction led the craftsmen to make mistakes which had to be corrected laboriously by a process of trial and error. Surviving versions of the trestle dining table designed by Philip Webb for 'Red House' in 1859 (cat. no. 6; not illus.) frequently bear traces of the modifications and alterations needed to strengthen the structure and achieve stability. In addition to such problems in the production of the furniture Morris was hopelessly under-capitalised and he could never afford the necessary machines to by-pass the lengthy hand-working involved in the manufacture of the Firm's wares, which inevitably meant that the 'Morrisian' style was very expensive to achieve. For instance, the hand-woven 'Hammersmith' carpets (see above) cost as much as four guineas per square yard, which was a huge sum at the end of the nineteenth century, the sort ofexpenditure which was far beyond the means of the average middle-class household. However the Firm's textile products have survived in remarkable condition owing to the durable quality of the materials and the meticulous hand-work. J. W. Mackail in his illuminating biography of William Morris (pub. 1899) records the fact that the very high cost of the decuraiions carried out by the Firm in the Green Dining-room at the South Kensingron Museum (now the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1867) came to be seen as a good investment as the scheme had not required any repairs or maintenance beyond the repainting of the ceiling in the space of thirty years. Newly cleaned and restored the room can again be seen in all the richness of the original gilded and painted ornamentation, an example of the splendour of the 'Morrisian method'. In his book on The English Revival in Decorative Art published in 1911 Walter Crane wrote:

The great advantage and charm of the Morrisian method is that it lends itself to either simplicity or splendour. You might be almost as plain as Thoreau with a rush-bottomed chair, a piece of maittng, an oaken trestle table; or you might have gold and lustre (the choice ware of William De Morgan) gleaming from the sideboard, and jewelled light in the windows, and the walls hung with a tapestry.

Contemporary opinion inclined to the view that Morris was more used to splendour than simplicity; The Cabinet Maker and Art Furnisher in discussing the Manchester Exhibition included the following comment:

That Messrs. Morris & Co. should seek business and reputation in the wealthy city of Manchester is most natural, for it requires a long purse to live up to the higher phases of Morrisean taste.

Morris himself was deeply disappointed at the failure of the Firm to live up to the ideals of its original prospects in which he said: '. . . it is believed that good decoration, involving rather the luxury of taste than the luxury of costliness, will be found to be much less expensive than is generally supposed.' Rather the reverse proved to be the case, though the innumerable 'artistic' interiors which were decorated with Morris paper, hung with Morris chintz and furnished with a 'Sussex' chair or two — which, at a few shillings each must be seen as cheap by any standards — were the visible monument to Morris's idealism and a practical realisation of his socialist theorising.

The firm of Morris, Marshall, Faulkner and Co. was founded in 1861, and set up business premises at 8 Red Lion Square near to the studio which Morris once shared with Burne-Jones. Both Ford Madox Brown and Rossetti claimed responsibility for suggesting the idea of the decorating firm, but some such plan must have been in Morris's mind for a long time, probably since the collapse of his ambitions to be first an architect and then an artist. His conviction that he could succeed in this undertaking grew out of his success in providing himself with his own personal 'palace of Art' in 'Red House', and the notion of being an old-fashioned tradesman obviously appealed to him. In later years, when the Firm was carrying out work on a house, a board would be put up outside advertising the activities of 'Morris and Company — upholders', an archaism for 'upholsterer' which even a century ago must long have fallen into disuse. Another aspect of owning his own company, which must have been of great importance to Morris, was the assurance it gave him of being able to conduct the whole of his life on his own terms. The Firm was to exact considerable sacrifices from its owner, first the move from his beloved 'Red House', and then, during the many years of his financial instability, all his available capital, but he made these sacrifices of necessity to retain his freedom.

Sideboard by Philip Speakman Webb. 1861. Click on thumbnail for larger image.

Originally Ford Madox Brown, Rosseti, Edward Burne-Jones and Philip Webb as well as Morris, P. P. Marshall and Charles Faulkner were partners in the Firm. All provided designs for the Firm's products with the exception of Faulkner, who was appointed book-keeper. Marshall was a surveyor and sanitary engineer, but even he contributed designs for furniture and cartoons for glass. The main business of the Firm in the early years was in making ecclesiastical stained glass, which was in considerable demand as a result of the 'ritualist' revival and the great expansion of church building which took place in the mid-nineteenth-century. Philip Webb designed furniture and assisted the shaky finances of the Firm by persuading his architectural clients to employ Morris and Co. as decorators. The sideboard dating from 1861 with its hooded canopy was one of the most characteristic of the Firm's early designs, and echoes the form of the hooded settles which were made for 'Red House' and Old Swan House. The side-table (cat. no. 8; not illus.) was made for Major Gillum, a faithful patron of Rossctti and of Webb, from whom he commissioned his commercial premises as well as his own house. Philip Webb is also alleged to have made jewellery designs for the Firm which were included in the 1862 exhibit. These were executed by the working jewellers. Hill and Mosley, who occupied the ground floor premises at 8 Red Lion Square. Burne-Jones designed glass and tiles, indeed before the association with De Morgan he spent many hours hand painting tiles assisted by Charles Faulkner's sister Kate. Later he was to design a great series of tapestries, including cat. no. 26, which was once at Stanmore Hall.

Sussex Chairs by Rossetti, Mortris, and Brown. 1861. Click on thumbnail for larger image.

Madox Brown and Rossetti both designed stained glass, and both are credited with designs for furniture products of this period. The 'Rossetti' chair is based on a provincial French prototype in common use in the early nineteenth century, like the 'Sussex' chair which is also based on a traditional country prototype allegedly found by Madox Brown. The extent of Madox Brown's contribution to the furniture production of the Firm is rather difficult to assess. He is said to have made designs for eight different chairs (see Madox Brown's "Designs for Furniture" in The Artist, XXII 1898, p. 41) but only one is illustrated, a very common type of occasional chair with the spindles in the back formed like bamboo, a type which seems to have been part of the furniture of nearly every ballroom in the Regency period. E. M. Tait, in The Furnisher (Vol. HI 1900-1 pp. 61-3) credits him with what he describes as: 'Perhaps the most interesting of the chair designs . . . the Sussex chair, with its quaint-shaped seat,' — this must be the round-seated chair (cat. no. 12) which is, indeed, traditionally ascribed to Madox Brown.

Ajustable Chair (Morris Chair) Click on thumbnail for larger image.

The 'Morris' chair was also based on a country prototype, found in this instance by George Warington Taylor in the workshop of a carpenter named Ephraim Colman at Hurstmonceaux in Sussex. A description and sketch of the chair was sent to Webb in about 1866. This chair was widely copied, notably by Gustav Stickley at his Craftsmans Workshops in Grand Rapids, U.S.A. Warington Taylor, who succeeded Faulkner as business manager, was instrumental in putting Morris and Company on a stable financial footing. He joined the Firm in 1865 and by the time of his death, in 1870, its business affairs were at last in good order. During his time at the Firm two important secular decorating commissions were undertaken, the Green Dining-room at the South Kensington Museum, already mentioned above, and a year before this, the Armoury and Tapestry Rooms at St. James's Palace. The commission to carry out the work at St. James's Palace must be regarded as a turning point in the Firm's reputation, and the results must have pleased the Office of Works, as Morris and Co. were again asked to undertake the decorations carried out in the Palace in 1880. The silk damask, 'Oak' (cat. no. 31), was designed to provide hangings in the throne room. In the form shown here, crimson and gold pure silk hand-woven brocaded damask, it was the most expensive material stocked by the Firm. The original estimate for making the curtains was �750; after protests from the Office of Works the sum was reduced, but only by the expedient of altering the design and leaving offhand-embroidered ornamentation which had been included in the original specification. Mackail has pointed out that these St. James's Palace commissions could have ensured an easy prosperity for Morris and Co. had Morris himself been prepared to make any kind of conventional com- mercial compromise, but this was the very course which he was temperamentally incapable of following. The years following Warington Taylor's untimely death saw the consolidation of Morris's decorative talent; the characteristic wall-paper and fabric designs for which he was, and is now, best known date from the 'seventies and 'eighties. Earlier attempts at wall-paper designing had produced the 'Trellis' with its birds by Webb — who must have been very attached to this paper as he used it extensively at Standen which was fitted up in the 'nineties, thirty years after it had been designed — the 'Daisy', which was very popular, selling consistently well for half a century; and the 'Fruit' a simple transverse pattern without any of the flowing quality of the later designs.

The Knights Departing [an Arras tapestry] by Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones. 1889. Click on thumbnail for larger picture.

Morris's first experiments with dyeing and printing fabrics were made in conjunction with Thomas Wardle at Leek in Staffordshire in 1875, and some of the results were included by Wardle in his exhibit for the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1878. The woven textiles were produced from about 1877, when a French weaver from Lyons named Bazin was brought over to teach Morris the complex techniques of Jacquard weaving. The so-called 'Arras' tapestries were first tackled in 1879, and the installation of high-warp looms at Merton Abbey in 1881 allowed larger panels to be undertaken. The Holy Grail series was originally designed by Burne-Jones for Stanmore Hall in 1894. The hangings for 'Red House' which Morris called tapestries, were, in fact, embroideries, and the designing of embroideries was undertaken from the early years of the Firm, many of them executed by needlewomen in Morris's family and immediate circle, among the most accomplished being Henry Holiday's wife Catherine, and later Morris's younger daughter, May, who luok over the managing of the embroidery department. J. H. Dearle, who joined the firm in 1878 was responsible for a number of the embroidery and textile designs, including the 'Squirrel' (cat. no. 33) which dates from the 'nineties and some of the simplified borders on repeats of Burne-Jones tapesrry designs. Dearie and W. A. S. Benson collaborated on wall-paper designs for Morris and Co. in the 'nineties.

Textile dyeing, weaving and printing all became more practicable with the acquisition of the workshops at Merton Abbey which provided the much needed space and the right type of water for the dyeing operations. It was intended that William De Morgan should also install his kilns at Merton so that all the operations necessary to produce the complete Morris interior could be undertaken under one roof, and De Morgan accompanied Morris on a number of his expeditions to look at likely premises. At one point it seemed possible that the Cotswold village of Blockley, very close to Chipping Campden, would provide a suitable site, thus anticipating by nearly a quarter of a century, the establishment of the 'Cotswold School', but Morris's business advisers were more realistic than C. R. Ashbee's about the difficulties and expenses involved in having workshops a hundred miles from the showrooms.

In the event De Morgan did not stay long at Merton, in spite of the reasonably convenient location, he found the journey prejudicial to his fragile health, and he moved in 1888 to Fulham. Decorating commissions which employed all the varied talents of Morris and his associates included work on No. 1 Palace Green for George Howard, Earl of Carlisle, started in 1868, with panelling (cat. no. 24), designed to incoporate Burne-Jones's beautiful 'Cupid and Psyche' scries, still in the precise and delicately detailed style which had been used for the St. James's Palace doors and panels; 1 Holland Park for Alexander lonides, begun in 1876; Philip Webb's Rounton Grange, designed for Sir Lowthian Bell, for which embroidered hangings were designed by Morris and Burne-Jones in about 1872; more hangings were designed for Bell's daughter, Mrs. Ada Godman, in 1877 (cat. no. 25) the original design inscribed 'Mrs. Godman. Design for embroidered hanging (artichoke design)' is m the Victoria and Albert Museum.

In the 'eighties 'Clouds' was decorated for the Hon. Percy Wyndham, and in the 'nineties, Stanmore Hall for William Knox d'Arcy and 'Standen' for Mr. Beale. In the early years of the Firm almost all the furniture was designed by Philip Webb, although Warington Taylor had tried to interest Morris in a less uncompromising style, he met with little success and it was only when Morris's interests were engaged elsewhere that a new style was introduced by Webb's assistant, George Jack.

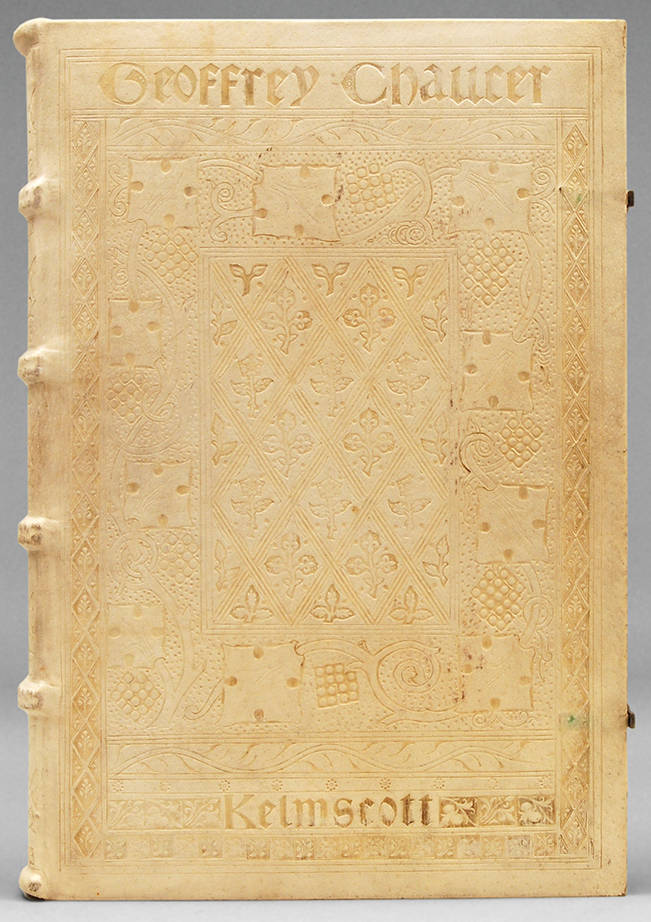

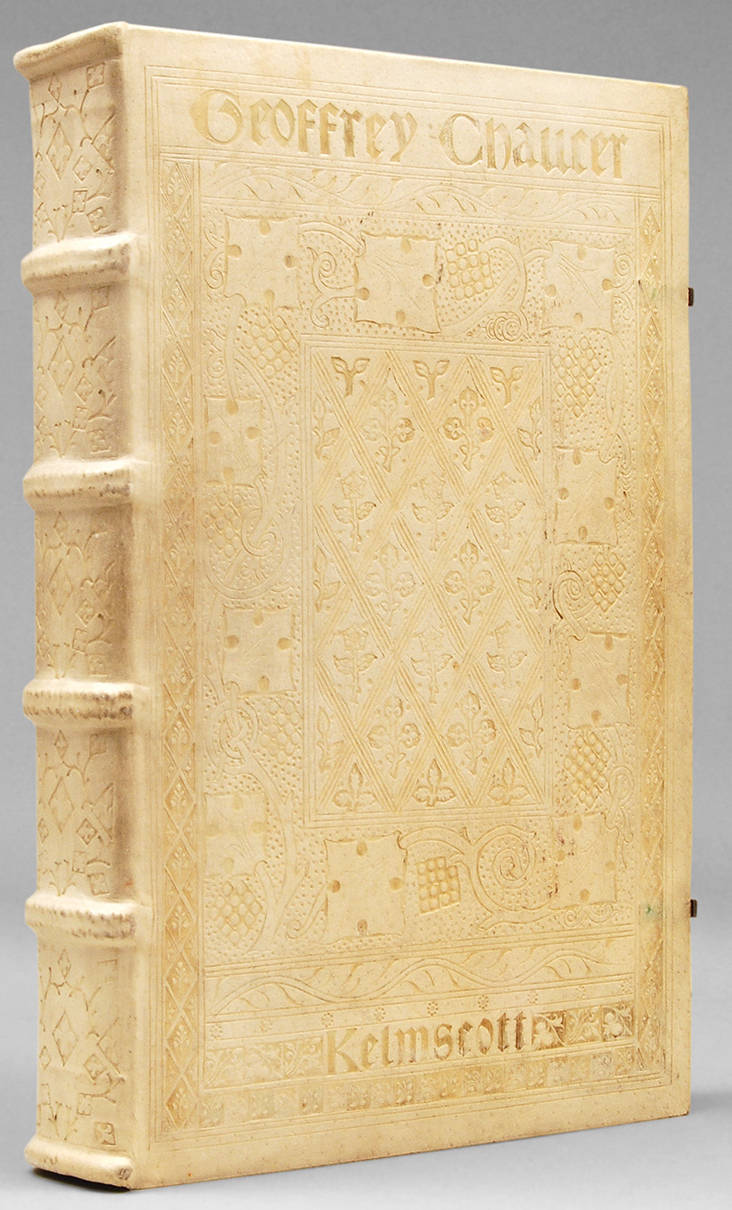

Left to right: Three views of the Kelmscott Chaucer. [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

Superficially conventional in proportion and ornamentation, Jack has taken eighteenth century forms and remade them in a way that is reminiscent of the designs of A. H. Mackmurdo. The debt to Webb is apparent in the arrangement of the panelling, but the cabinet work is of the finest quality, no doubt due to the fact that at about this date (i.e. 1887) Morris and Co. had acquired one of the workshops in Pimlico owned by the cabinet-making firm, Holland & Sons. Jack was made chief designer to the Firm in about 1890 and his furniture was used at Stanmore Hall. In the 'nineties Morris's attention was almost entirely absorbed by his Kelmscott Press work. He was able at last to concentrate on his earliest interest, book design and typography. This was a separate venture from the Firm and is not relevant to its history, but the fusion of all Morris's interests, as an artist, a pattern designer and a poet are united in his printing venture. This is nowhere better demonstrated than in his last great work, the famous Kelmscott 'Chaucer' (cat. no. 222).

Related Material

References

Morris and Company. London: The Fine Art Society, 1979.

Last modified 5 November 2006