This essay is based on a talk given at Cefn Tilla, near Usk in Monmouthshire, a large country house that Wyatt himself extended. The talk was in aid of a fund to restore his and other family members' dilapidated graves, and the path giving access to them, in the local churchyard. Many thanks to the Usk Civic Society, especially Shan and Philip Henshall, for organising this very special event. It was a unique chance to promote the name and reputation of a distinguished architect who himself was far from self-promoting. The images here may be used without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the source and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one. [Click on the images to enlarge them, and usually for more information about them.]

Matthew Digby Wyatt was born in Rowde in Wiltshire, near Devizes, on 28 July 1820 — just over a year after the birth of Queen Victoria. He enrolled in the Royal Academy Schools in 1837, the very year she came to the throne. He would become not only one of the most distinguished members of a distinguished family, but one of the most distinguished architects of the mid-Victorian era, carrying through a strain of classicism which would re-emerge in the later period as the Gothic Revival faded. At the same time, he would stand at the helm of some of the most significant enterprises of his age.

Early Days

Troy House, Monmouthshire, photomechanical print c.1890-1900 (Library of Congress image, ID LC-DIG-ppmsc-08713).

Digby Wyatt, as he was known, grew up and was educated in Wiltshire, but from his earliest years had a strong connection with Monmouthshire. His Uncle Arthur (1755-1833), his father's next youngest brother, was the agent of the Duke of Beaufort, the manager of an estate which included Raglan Castle in that county, the original seat of the Beauforts. Arthur Wyatt lived in and looked after the interests of Troy House on the Duke's estate, as well as being responsible for the castle. The Wyatts were a close family, and his young nephews Thomas Henry and Matthew Digby would come to stay with him in the summers. John Martin Robinson, the Wyatts' biographer, tells us that they loved staying there, suggesting that "the romantic old house stimulated their love of architecture" (202).

But nature as much as nurture was involved in their choice of careers. Their father Matthew's primary profession was that of barrister and specifically Metropolitan Police magistrate. However, like his brother Arthur, Matthew Wyatt Senior was a land agent as well, in his case for the Marquess of Downshire in Ireland. Buildings clearly had a large place in the family background. The journalist and politician Woodrow Wyatt, a more recent member of the family, points out that the family tree includes twenty-eight architects, "all of skill and mostly of distinction," and twelve others who were land-agents, not to mention "ten sculptors, painters and carvers" (vi). The boys' father also had an artistic streak, and was an amateur watercolorist of some skill. With such forebears in mind, Woodrow Wyatt declares, "It is impossible to study my family and retain a belief that environment is more important than heredity" (vii-ix).

Frontispiece of Specimens of the Geometrical Mosaic of the Middle Ages, the pattern here having been put together from mosaic work "selected from churches at Rome and in its immediate vicinity" (Wyatt 24).

Thomas Henry, who was thirteen years older than his brother Digby (as the latter is usually known), entered on his professional life as an architect first. By the time Digby joined him as a pupil, at the age of sixteen, Thomas Henry already had a thriving practice. Still in his teens, Digby swiftly justified his choice of career by winning the Architectural Society’s prize for an essay. After completing his practical training with his brother and at the Royal Academy Schools, he rounded off his architectural education in the same way that most young architects did at that time, by touring the most widely admired buildings of the Continent. From his two years in Europe came many drawings, and the first of a whole series of books, The Geometrical Mosaics of the Middle Ages (1848).

On his return, the younger Wyatt could easily have spent the rest of his professional life in partnership with his brother. The practice was growing steadily. However, the two young men were rather different. Like so many Wyatts, Thomas Henry married his cousin, uncle Arthur's second daughter Arabella, and was particularly active in Monmouthshire, designing (for example) the Sessions House in Usk. Robinson gives him a final tally of over four hundred buildings (204). But he also adds rather damningly that Thomas Henry's output was more remarkable for quantity than quality. Even the Sessions House seems, to architectural critic John Newman, "very old-fashioned for its date" (593). For the younger of the two Wyatts, it would be quality rather than quantity. Whatever he designed, even if it was on a small scale, would be something special: Christchurch in the little Welsh village of Coed-y-paen, for example, which he designed in the 1850s, strikes Newman as "[d]]ignified and coherent" (310).

Christchurch, Coed-ye-paen designed by Wyatt in the 1850s.

However, buildings (which Digby Wyatt continued to design throughout his career) were only a part of his achievement. In general, he took a much more scholarly approach than his brother, and had a greater diversity of interests. He liked writing about the arts, and enjoyed all kinds of design-work, everything that gave distinction to both the exteriors and the interiors of buildings — not only mosaic-work, but also metalwork, tiles and stained glass, for instance. He became vastly knowledgeable about them too. Such breadth of interest was less unusual then. It was an age in which versatility was encouraged: the age of Ruskin, who saw architecture as inextricably linked to other visual arts, saying, for example, "My wish would be to see the profession of the architect united, not with that of the engineer, but of the sculptor" (24). Here Ruskin had in mind, specifically, architectural sculpture, reliefs and carvings on the façades of buildings. Digby Wyatt was rather critical of Ruskin: he felt that he had given inadequate credit for his views to A. W. N. Pugin, because of the latter's conversion to Roman Catholicism; he also felt that he failed to recognise the inevitability of change (see Pevsner 98). But the remark about architecture and its sister arts struck home. Like all the great Victorian architects, from Pugin himself to William Burges, Gilbert Scott and G. E. Street, Digby Wyatt became adept at designing in a variety of media.

During the next few years, therefore, Digby Wyatt struck out in various directions. He wrote articles, and was invited to talk and advise. His personality stood him in good stead. He was far from drily scholarly. Rather, he was clubbable, a team-player as well as leader, and good to have on committees — even if, or perhaps because, he could be rather "excitable" at the meetings (Piggott 97). Some of his greatest achievements were collaborative, and the key roles he played in them is apt to be forgotten. This is certainly the case with his first big, indeed probably his biggest, project. In 1849, the Society of Arts asked him to go to Paris to report on the French Exposition of that year. He went over with Henry Cole, who would be the moving force behind Britain's own Great Exhibition of 1851. The direct result of this was his appointment as "Special Commissioner and Secretary to the Royal Commission" which organised the setting up of the Crystal Palace in Hyde Park. From this point, Nikolaus Pevsner claims, "the buildings are only foil to his other achievements" (97).

The Crystal Palace

Left: Constructing the Crystal Palace in Hyde Park: raising the ribs of the transept roof. Right: The Byzantine Court at the Crystal Palace at Sydenham.

That is not strictly true. In the first place, the Crystal Palace itself owed much to him as executant architect: it was he who was finally "responsible for realizing the outline design" first sketched by Joseph Paxton for the giant glasshouse (Stuart 387), and who was able to explain it in detail afterwards, both for the general public and for experts who wished to know the details of the construction. There were also some very important buildings to come. But it is true that his current administrative responsibilities were huge: as he said himself, "Upwards of £50,000s worth of work was directed by me as sole architect" (qtd. in Robinson 207). Once the enormous structure was raised, he was also in charge of its interior design, and arranging the exhibits, both of which were incredibly complex tasks. As for the latter, the displays included everything form the Koh-i-noor diamond to heavy machinery, ranging from a mechanical envelope folder to locomotives. Many of the mechanical devices had to be shown in action, with suitable safety measures taken. Usually we think of the Crystal Palace as the work of Paxton, and the interior as the work of Owen Jones (an expert of ornamental design, and Digby's good friend), but there was no aspect of this great enterprise in which he was not involved.

This was fully recognised at the time: Prince Albert gave him a gold medal and monetary reward for directing the project. When it came to taking the structure down, and erecting it again at Sydenham, Digby Wyatt was, if anything, more involved, personally designing the architectural courts in different styles. Pevsner writes rather witheringly about the way he borrowed and copied "from anywhere" (96) and displayed various motifs "without any tension" or even notable "accents" (97); but these courts should be exempted from such criticisms, because his aim here was to educate the public in the broadly different kinds of architecture of the past, in a generic manner. The Routledge guide to the new Crystal Palace describes the enterprise very much in pedagogical terms, for example, when referring to restored medieval doorways in one of the courts: "Probably a more striking instance is not to be met with of the value of the instruction which the great school of the Crystal Place affords to visitors, than those restored doorways" (86). Overseen by Digby Wyatt, these and the other contents of the architectural courts reveal the future Slade Professor in the making, a scholar wishing to impart to others his enthusiasm for a whole range of historic styles.

Other Major Collaborations

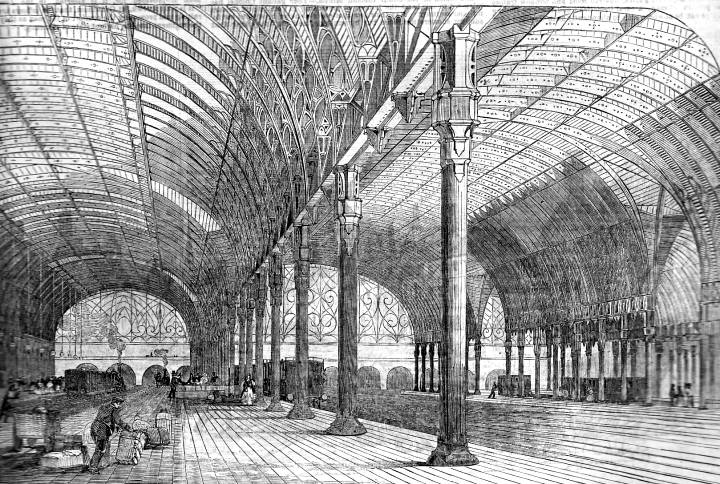

Right: Durbar Court at the Commonwealth Office. Left: Ironwork at Paddington Station.

Two other important collaborations were with Brunel and Owen Jones on the Great Western Railway Terminus at Paddington (1850-55), for which he designed the marvellous metalwork, and with George Gilbert Scott on the Foreign Office in Whitehall (1868). At Paddington too, his work was influenced by Jones, especially by Jones's detailed knowledge of Moorish patterns: the designs of the cast-iron capitals at the top of the columns are similar to those in Jones’ designs, influenced by the Alhambra. There is indeed something distinctly Arabic not only about these but about other railway platform columns: it seems to have become a popular motif. Here, even the window surrounds, window-guards and platform canopy ends pick up the theme.

Versatile as he was, Digby Wyatt comes out very well from the notorious "Battle of the Styles" over the key buildings at the heart of government. In 1855 he had been appointed Surveyor of the East India Company. When pressure was put on George Gilbert Scott to produce a classical design for the Foreign Office, rather than the neo-Gothic one on which he had set his heart, Digby Wyatt helped to persuade him to take advice from the Office of Works, and prepare a more acceptable design. Scott wrote later that he met Digby soon after receiving the advice, and that he too

very disinterestedly, urged strongly the same view — I say disinterestedly, for had I resigned he would beyond a doubt have had the whole design of the India Office, instead of a half of It, committed to his hands. I was in a terrible state of mental perturbation, but I made up my mind, went straight in for Digby Wyatt's view, bought some costly books on Italian architecture, and set vigorously to work to rub up what, though I had once understood pretty intimately, I had allowed to grow rusty by twenty years' neglect. I devoted the autumn to the new designs, and, as I think, met with great success. [198-99]

Moreover, as in the case of the Crystal Palace, Digby Wyatt had some important, probably essential, input into the design itself. Just after recalling the difficult period leading up to this eventual success, Scott admits in passing that although the "India Office, externally, was wholly my design, ... I had adopted an idea as to its grouping and outline, suggested by a sketch of Mr. Digby Wyatt's. This I thought very excellent" (200). Robinson is certainly convinced that "the over-all composition of the park-front of the Foreign and India Offices owes much to Digby," noting that although the "interior of the India Office was ... entirely Digby's," the two architects "were paid jointly 5 per cent on all contracts"(210).

The whole affair had been exceptionally fraught for Scott, "the battle, though long one of style, came at last to be almost for existence. I felt that I should be irreparably injured if I were to lose a work thus publicly placed in my hands, and I was step by step driven into the most annoying position of carrying out my largest work in a style contrary to the direction of my life's labours." (200-01). There is no doubt at all that Digby Wyatt was a great support, and also a great practical help to him, at every stage.

When it came to the interior of the Foreign Office, Digby Wyatt, of course, had free rein. Its dazzling Durbar Hall is the climax of its grand stairway, offices and suites. Pevsner calls its style "a kind of Genoese High Renaissance" (96) but this hardly does justice to the mélange of styles within that: doric columns on the ground floor, ionic on the first floor, both of polished red Peterhead granite, and Corinthian columns of grey Aberdeen granite on the top floor. Greek, Sicilian and Belgian marble have been all been used. Elaborate ceramic friezes, sculptural reliefs and busts adorn the sides. Robinson calls it "the supreme example of the South Kensington style" (213), but there is also an Oriental flavour here, especially in the sculptured reliefs showing scenes from imperial history, but perhaps most noticeably in the fact that the top was originally open to the skies.

Notable Later Work

Addenbrooke's Hospital, Cambridge, as remodelled by Wyatt (now the Cambridge Judge Business School).

Digby Wyatt continued to be involved in the spin-offs from the Great Exhibition of 1851, not just in its re-erection at Sydenham but in the related project at South Kensington: he was now acting as the art referee for the museum which would develop into today's Victoria and Albert Museum. In this connection he wrote as many as a thousand recommendations, revealing an extraordinary breadth and depth of knowledge about the most obscure objets d'art. He continued to write books and deliver papers on a huge range of subjects as well, from illuminated manuscripts and ivory sculptures to ceramics. The range was across time as well as across media: "The Present State of Art in Italy" was the title of a paper that he delivered to the Society of Arts 1862; in 1868 he delivered a paper to the Institute of Architects (the future RIBA) on “Foreign Artists employed in England during the Sixteenth Century.” In the following year he was knighted by Queen Victoria at Osborne (where he had once advised Prince Albert on the floor tiling) and appointed the first Slade Professor of Fine Art at Cambridge. All in all, the sixties were quite literally a golden decade for him: along with many other honours and offices, he had received the Gold Medal of RIBA in 1866.

Yet throughout he continued to practice as an architect, undertaking a variety of commissions — restoring churches, country and town houses for the wealthy, and business premises like the Lloyds Bank complex on Gracechurch Street in the city (not completed until 1877, the year he died, but since demolished). Among the buildings of distinction for which he was responsible in the hectic '60s and '70s were: the old Addenbrooke's Hospital building on Trumpington Street in Cambridge (1863, since splendidly adapted to become the Judge Business School); the Rothschild Mausoleum in West Ham Jewish Cemetery (1866, but sadly vandalised in our own century); Bristol Temple Meads Station (1865-78); and his major additions to the Royal Indian Engineering College on Cooper's Hill Green in Surrey (1870-71), later used by Brunel University and now being adapted for residential purposes. In this century the reputations of his writings and his contributions to the built environment have been reversed: the latter are now perceived as more important than the former.

Domestic Life

Fan designed and painted by Wyatt, depicting "The Triumph of Love" — a birthday present for his wife.

In January 1853, when Digby Wyatt was still in his early thirties, he had got married in Usk as his brother had done — not to a cousin, in his case, but to Mary Nicholl, from a prominent local family. Born in 1812, she was already past forty, which might be one reason why the couple remained childless. Still, he seems to have been very much part of the family. He rebuilt The Ham, a large house in Llantwit Major, Glamorgan, for Mary's brother, completing it in 1869, and would later design her sisters' graves. More happily, the couple shared a hobby: collecting fans. They collected about four hundred of them from all over Europe and East Asia, eventually in 1876 donating the collection to the museum for which Digby Wyatt had recommended so many other kinds of acquisitions. One of the fans in the Victoria and Albert Museum has a particularly personal resonance: it is one that he designed and painted himself, as a birthday present for his wife, in 1869. The images on the fan represent the "Triumph of Love," and the inscription reads, in part, "For Love is Heaven and Heaven is Love."

Dimlands Castle, Llantwit Major, Glamorganshire, where Wyatt hoped to recover his strength after years of intense work.

Robinson points out that Digby Wyatt's prolific elder brother rose to be president of the Royal Institute of British Architects in 1870, and was awarded a gold medal for his achievements by it in 1873) but that he lacked one quality: a sense of humour (he goes so far as to claim that he "never said a really funny thing in his life," 218). This could never have been said of Digby Wyatt. Both he and his wife were close friends of the artist and nonsense=poet, Edward Lear, and had contemplated building a villa near his in San Remo, until they learned of a new development there that ruined his view. Instead, they accepted one of the Nicholl houses in Glamorganshire, a quaint fortress-like building called Dimlands Castle, where, still in his fifties, he died on 21 May 1877 and was buried at Usk. His tomb was designed by his brother, Thomas Henry Wyatt, who himself died in 1880. Mary Wyatt died in 1894.

Wyatt's grave, designed by his brother Thomas Henry Wyatt, in the churchyard of the Priory Church of St Mary, Usk.

Bibliography

Crook, J. Mordaunt. William Burges and the High Victorian Dream. Revised and Enlarged Edition. London: Francis Lincoln, 2013. [Review]

Newman, John. Gwent/Monmouthshire. Buildings of Wales. Mew Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2002.

Pevsner, Nikolaus. "Sir Matthew Digby Wyatt." The Complete Broadcast Talks: Architecture and Art on Radio and Televion, 1945-1977. Ed. Stephen Games. London: Routledge, 2016. 94-101.

Piggott, Jan. Palace of the People: The Crystal Palace at Sydenham, 1854-1936. London: Hurst & Co., 2004.

Robinson, John Martin. The Wyatts: An Architectural Dynasty. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1979.

Routledge's Guide to the Crystal Palace and Park at Sydenham. London: Routledge, 1854. Internet Archive. Contributed by Boston Public Library. Web. 24 July 2019.

Ruskin, John. An Enquiry into some of the Conditions Presently Affecting the Study of Architecture in Our Schools. New York: Wiley, 1866. Internet Archive. Contributed by the University of California Libraries. Web. 24 July 2019.

Stuart, Emma. Entry on the Official Catalogue of the Great Exhibition, No. 309. Victoria & Albert: Art & Love. London: Royal Collection Publications, 2010.

The Triumph of Love. Victoria and Albert Museum. Web. 267 July 2019

Wyatt, Woodrow. Foreword. Robinson v-x.

Created 27 July 2019