ritish imperialism was predicated on two beliefs: that force would always prevail, and that no territory, or potential territory, was beyond the empire’s reach. This confidence in Britain’s power was all-pervasive as lands and resources around the globe were seized by political coercion, military conquest, and occupation. Sustained by the myth of invulnerability, British elites became the most successful colonizers on earth as they imposed western values and economic systems on the colonized.

Yet there is a significant difference between the myths of empire and the realities. In practice, British imperialism was anything but stable, and British power far from immutable or beyond challenge by the many who resisted occupation. The Indian Rebellion (or Mutiny) of 1857–59 demonstrated the limits of imperialism, and Britain’s wars in the final quarter of the nineteenth century were a constant reminder that the subjugation of distant countries was always a brutal challenge. Moreover, Britain’s imperial project was constantly eroded by its military failures as resources and manpower were stretched to their limits.

Perhaps the most lamentable example of this sort of weakness is the short lived but disastrous Anglo-Zulu war of 1879. This ‘imperial side-show’ had a ‘grim’ impact on British society (Knight 9). The British had set out to seize the lands of King Cetshwayo following a series of disputes between the Zulus, the British and the Boers, but the Zulus were unwilling to accept Britain’s political solutions and met the Army, led by Lord Chelmsford, with considerable military force. This conflict was crystallized in two (in)famous encounters: the Battle of Isandlwana (22 January 1879), and the Defence of Rorke’s Drift (23–24 January). In the first of these the Zulus overwhelmed and killed around 1,300 soldiers of the 42nd Foot, 2nd Warwickshires (later South Wales Borderers), whom Chelmsford had left in camp with insufficient defences; and in the second a garrison of only 138 of the same regiment was able to hold off a Zulu force of around 4,000. The British finally won the war at the Battle of Ulundi (4th July), but the massacre at Isandlwana and the near-extinction of Rorke’s Drift were reminders of the military’s – and the empire’s – frailties.

Isandlwana in 1992 with British grave cairns in the foreground.

How these engagements were treated politically has been considered at length in the vast literature exploring the conflict’s history. But equally interesting are the ways in which the battles were presented in terms of the visual information that was presented to the home audience. This pictorial discourse embraces painting, photography and illustration, and decoding these dense visual texts allows us to reconstruct contemporary attitudes to the war. It is also interesting to consider a neo-Victorian perspective on the battles in the form of two notable films, Zulu (1964), and Zulu Dawn (1979).

Art as Propaganda: Constructing the Mythology

The massacre at Isandlwana was perceived as a catastrophic failure, but the British authorities were careful to deflect public outrage and focused, instead, on the courageous fighting at Rorke’s Drift. In the words of Lady Elizabeth Butler, who painted a celebrated painting of the battle, the British resistance ‘shed balm’ on the ‘aching wound’ (184) of the earlier defeat. Such careful rewriting of the narrative asserted a sort of victory and was consistently presented to the public in official propaganda. Tellingly, eleven Victoria Crosses, the most awarded for any engagement, before or since, were awarded to survivors of Rorke’s Drift – a calculated strategy to emphasize British bravery rather than British losses.

This revisionism was also imposed in the form of visual material which appeared in the illustrated press and in a series of commemorative paintings, and each of these images partook in the making of the patriotic myths that surrounded the conduct of the Anglo-Zulu war. In this pictorial version of events the beleaguered soldiers at Rorke’s Drift were constructed as idealized types whose defence of a few buildings within a stockade was amplified so as to position them as defenders of the empire and of Britain itself. Rorke’s Drift becomes a surrogate for the Island Home, with its soldiers, the emblems of British resolution, holding back the enemy at the gate.

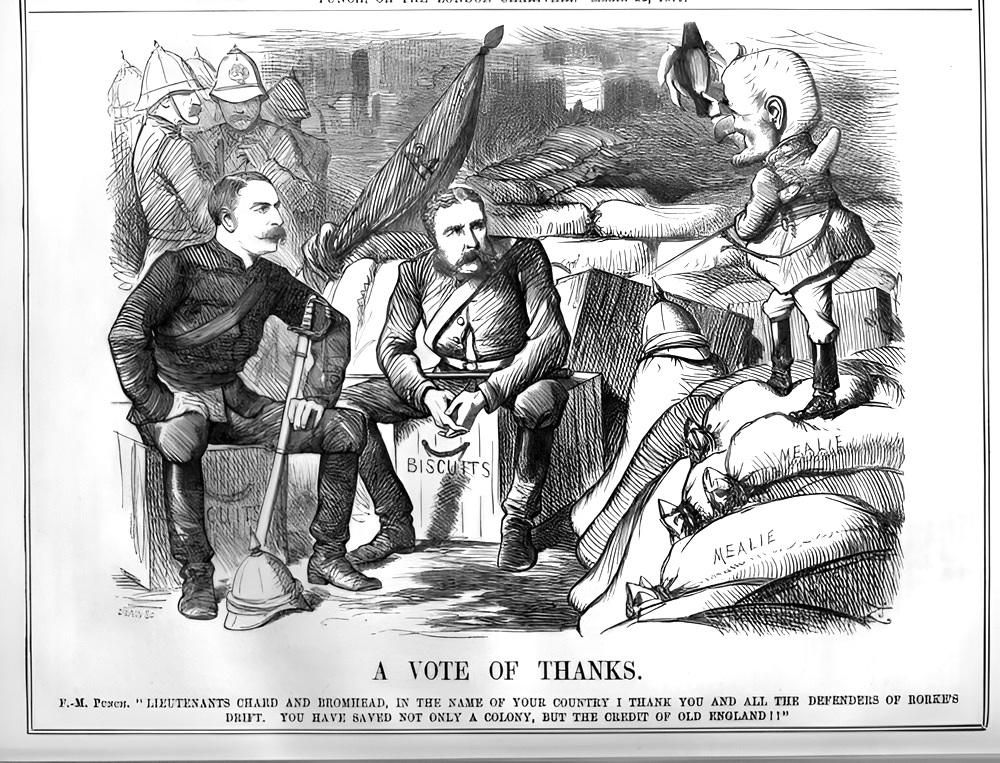

That imagined status was especially focused in the treatment of the commanding officers, Lieutenants John Chard and Gonville Bromhead. In A Vote of Thanks in Punch, for example, John Tenniel depicts Chard and Bromhead as exemplars of quiet resolution as they sit, prosaically, on biscuit boxes surrounded by the mealie sacks that were used for a barricade. Mr Punch, a surrogate John Bull, thanks them for their efforts: ‘In the name of your country I thank you … You have saved not only a colony, but the credit of Old England.’ Modest and unassuming, Chard and Bromhead are labelled the saviours of Britain.

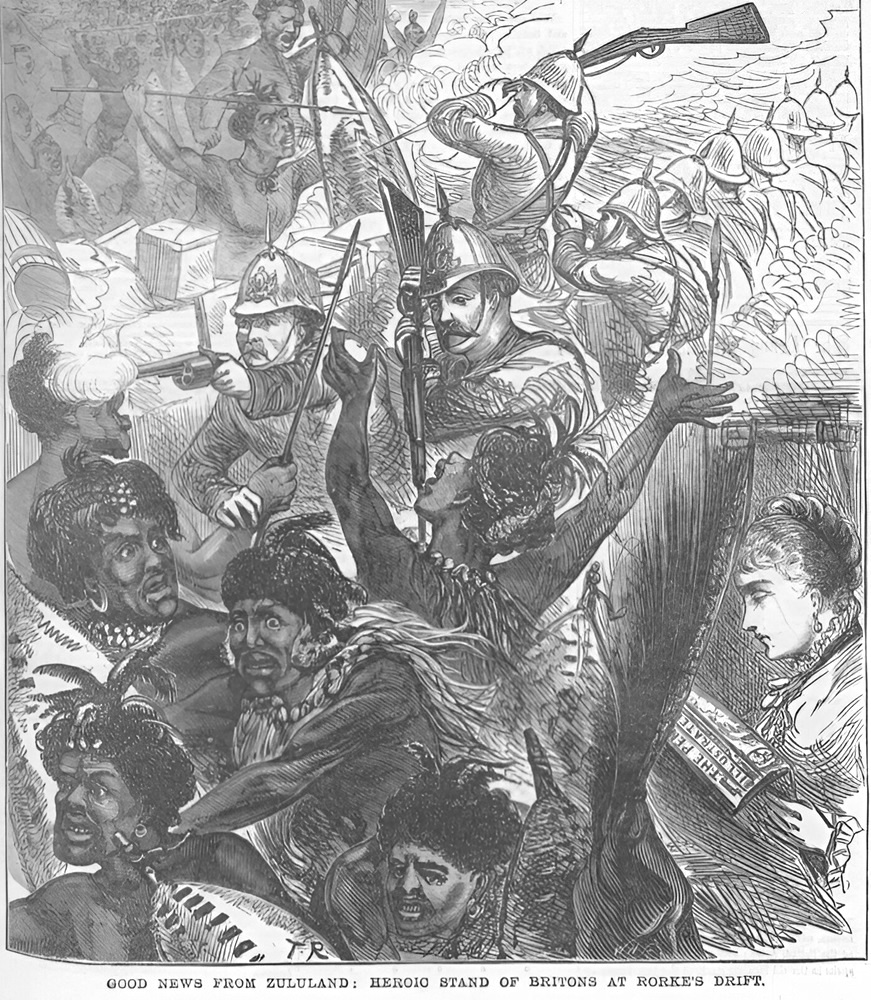

This idealizing concept is given a more general registration in a cartoon by an unknown hand in the Penny Illustrated Newspaper (1 March 1879). In this design the notion of the soldiers’ patriotic fortitude is realized by juxtaposing the home audience (represented by a middle-class woman reading the paper in the comfort of her lounge) with a vivid image of troops engaged in hand-to-hand conflict as they fight off a horde of Zulus, who are shown in stereotypical terms as savages. The diagonals stress the movement and intensity of the battle, but the reader at home is safely ensconced in her bourgeois sitting-room.

Propaganda responses: (a) Left: Tenniel’s A Vote of Thanks; and Right: an anonymous artist’s notion of Good News from Zululand. Both act as a form of reassurance as the empire creaked at the seams.

The contrast between the two domains of experience reveals the way in which the message of Rorke’s Drift was politically constructed. In the words of doggerel written by an anonymous author and published in the Western Daily Press (5 May 1879):

The battle raged with might and main

But all the demons in the land

Could not appal that plucky band

Not only did they save their lives,

But saved us all, our homes, our wives [6].

Such hyperbole acted as reassurance for a public which, as noted earlier, must have been aware of the vulnerability and isolation of British forces, whatever the official line. Indeed, exaggerated writing and visualizations set out to persuade audiences that Rorke’s Drift was ultimately not only a defence of the British and the Island Home, but a universal symbol of the British character. The ‘plucky band’ of defenders could see off any threat with what one commentator called ‘desperate valour’ (Lucas 353), and, by implication, so too could the British, embattled in a small country that imagined it was pitted against the world.

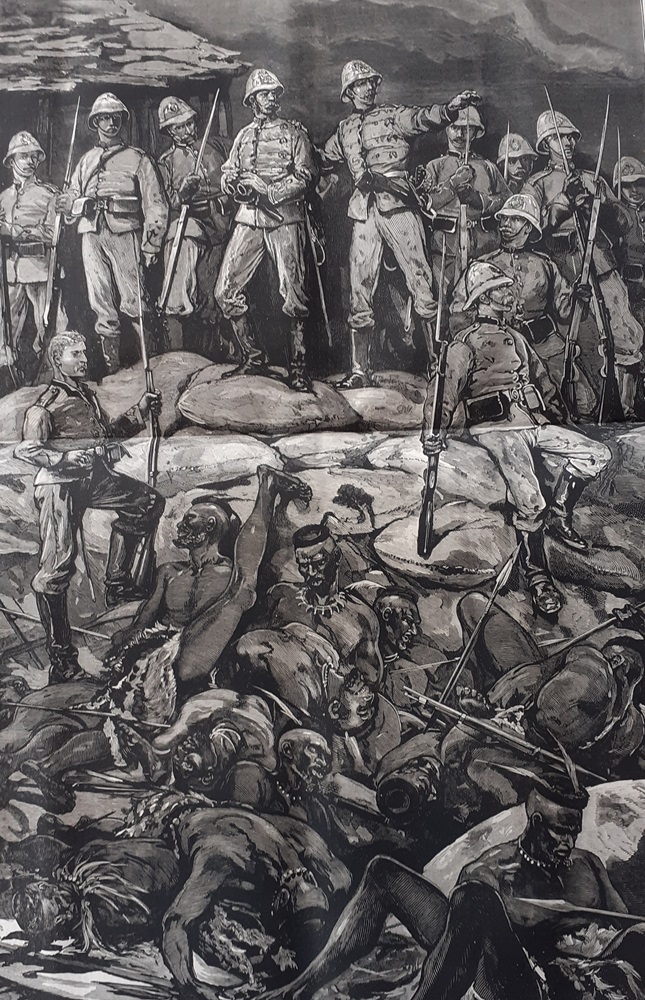

All that was needed, such propaganda insists, was an indomitable spirit. But that idea was further inflected with gender politics, with the insistence that protection of the realm – and of British culture – was a masculine duty. It is noticeable that the soldiers are praised for saving ‘our wives,’ the sort of woman who reads about the war in the Penny Illustrated, and there can be no doubt that Rorke’s Drift was regarded as another expression of male hegemony, as in the Graphic’s representation of the victors as they stand, triumphantly, over a pile of dead Zulus at the end of the battle. If the women were at home homemaking, it was men’s rightful place, the image argues, to protect the home and its empire. This belief system was naturalized in Victorian theorists writing of the difference between the genders and encapsulated in Tennyson’s much quoted lines in The Princess (1847):

Man for the field and woman for the hearth;

Man for the sword for the needle she:

Man with the head and woman with the heart;

All else confusion. (Tennyson 188)

A dramatic illustration showing the scale of the slaughter at Rorke’s Drift.

Perceptions of the Zulu war were entangled in this discourse, and visual art was used not only for political propaganda, as such, but also as a means of reaffirming conventional understandings of the role of men. Tennyson’s concept of the fearless man informs the war’s imagery, and it is embodied in the portraiture of the heroes and in the representation of the violence.

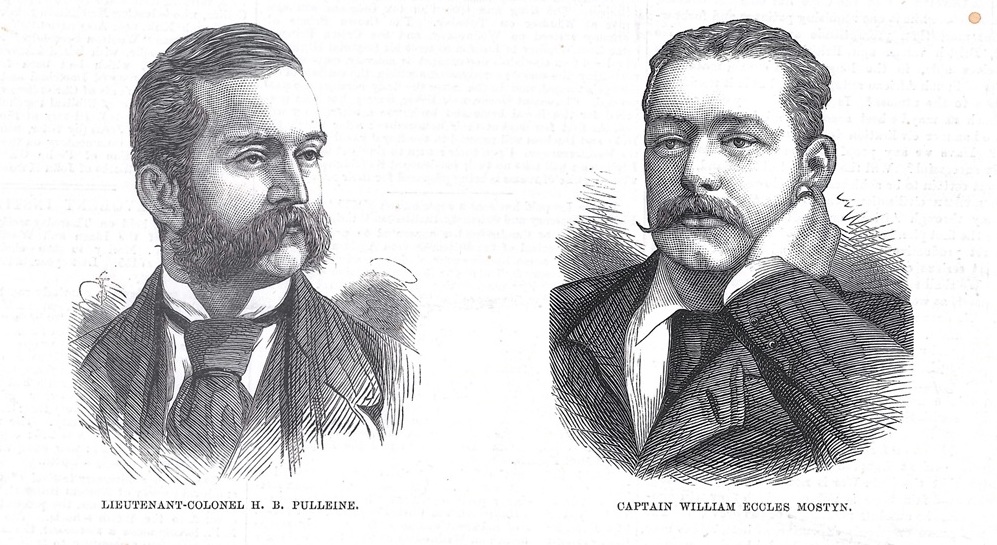

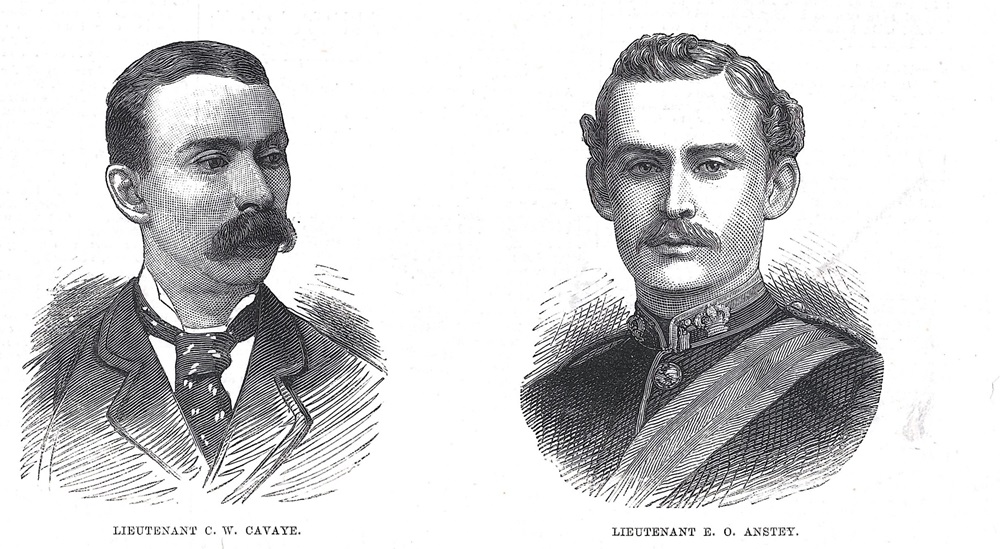

The soldiers of the Zulu war were presented to the public as celebrities who were both heroic and stereotypically handsome, with ‘good’ features acting as an index of a good character. More especially, artists drew upon the pseudo-language of physiognomy to represent the masculine virtues of resolute determination and courage in the forms of their imaged faces. The manipulation of portraits in order to express character as much as likeness is typified by the anonymous gallery of ‘Officers of the 24th Regiment killed at Isandula’ [sic] The Illustrated London News (March 8 1879). These images were based on photographs, but the artist tellingly manipulates the portraits so that each of them is characterized by a tall forehead, a well-defined jawline, a medium to large nose, and an intent, or ‘penetrating’ gaze. All of these signs denote ‘Resolution’ (Cowling 33), and the characters are further endowed with the hirsute attributes of well-defined hair and eyebrows and moustaches – signs which supposedly signalled virility and manliness. The officers were killed, but we can be sure, at least according to their physiognomies, that they met their end with the valour expected of men.

Images of the officers killed at Isandlwana – or at least idealized versions of them, with emphasis being placed on their handsome manliness. Pulleine, who was officer in charge in Chelsmsford’s absence, was noted for his complacency – though here he is endowed with a resolute physiognomy. He is commemorated in Brecon Cathedral.

More images, this time of Lts. Cavaye and Anstey. Comparison of the engraving of Edgar Oliphant Anstey with the photograph of him on the right shows how the artist idealized his features.

Masculine physiognomies are equally pronounced in the treatment of those who survived the conflict. Chard and Bromhead were subject to the process of idealization in two of the three epic paintings that represented the Defence of Rorke’s Drift and here, again, the beleaguered officers are shown as manly types.

In Alphonse de Neuville’s version, above (1880, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney), Bromhead is shown in near profile, while Chard is depicted, his large features prominently displayed, as he models courageous behaviour by fighting in the line with the men under his command.

A detail from Alphonse de Neuville’s representation of the Defence of Rorke’s Drift, with Chard fighting on the barricade.

Both characters have the ‘strong’ features that signal resolute characters and in Lady Butler’s treatment (1880, Royal Collection), likewise, the officers are depicted as firm-jawed symbols of manhood. As Samuel Roberts Wells observes, such ‘straightness’ in the disposition of the lips is a ‘facial sign of Firmness’ (72); the ‘stiffness of the upper lip’ (74), especially, is the emblem of unyielding courage, and one stereotypically associated with the unyielding character of the Victorian man.

Lady Butler’s treatment of the Defence of Rorke’s Drift.

In every case, the artists the artists endowed the soldiers with faces connoting a certain set of values. This strategy is the very essence of propaganda as it seeks to present a resonant sign which crystallizes a belief or attitude. The British warriors of the Zulu war were promoted as heroes, and they had to look like heroes too. In this way living individuals become icons – signs or types which transcend time.

Mythologies in Action: Movement and Race

A single ‘weak’ physiognomy, with a sloping forehead or a receding chin, would fatally undermine the propaganda-effect of these idealized images. There was, of course, no tolerance or representation of the terror that the men must have felt as they engaged the Zulus (although at least one soldier, Robert Jones, took his own life while suffering from what was probably post-traumatic stress disorder).

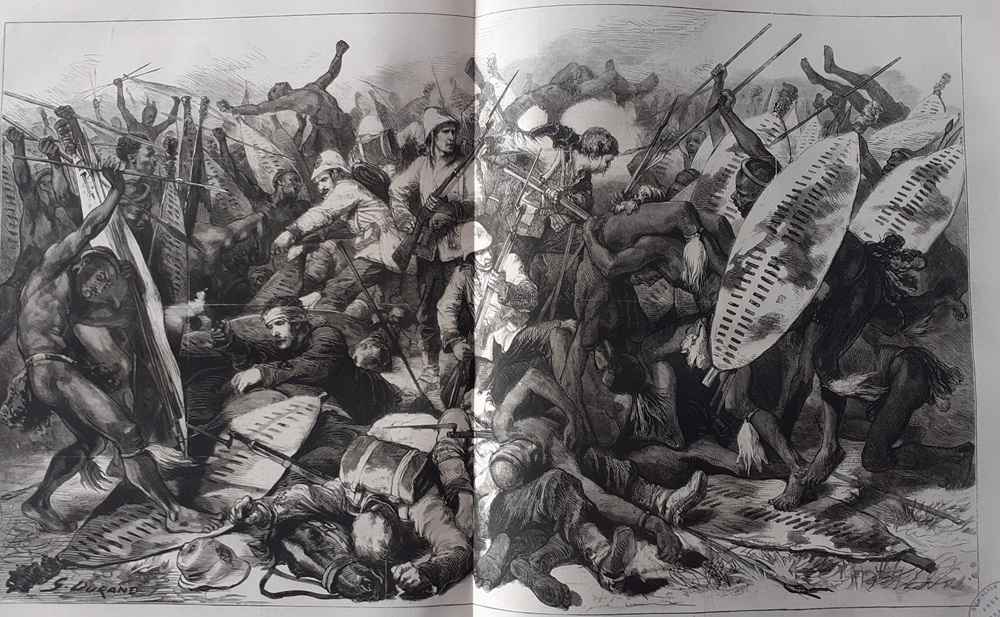

It is interesting to note, moreover, that courage and determination were invested not only in the visualized faces but in the treatment of gesture, stance, and action. Both of the engagements were a desperate ‘hand-to-hand struggle for life’ (Creswick 1, 41) and the sheer chaos of the encounters, as the British were ‘pinned like rats in a hole’ (Knight 53), is powerfully conveyed in several dramatic images. One of these is Godefroy Durand’s wood engraving of Isandlwana in The Graphic, which shows the British troops caught up in a vortex of bodies. The paintings by Neuville and Butler also provide dynamic representations of the desperate conflict at the Drift, and one by Charles Fripp, the struggle at the previous battle.

A desperate and gruesome image of the Battle of Isandlwana in The Graphic.

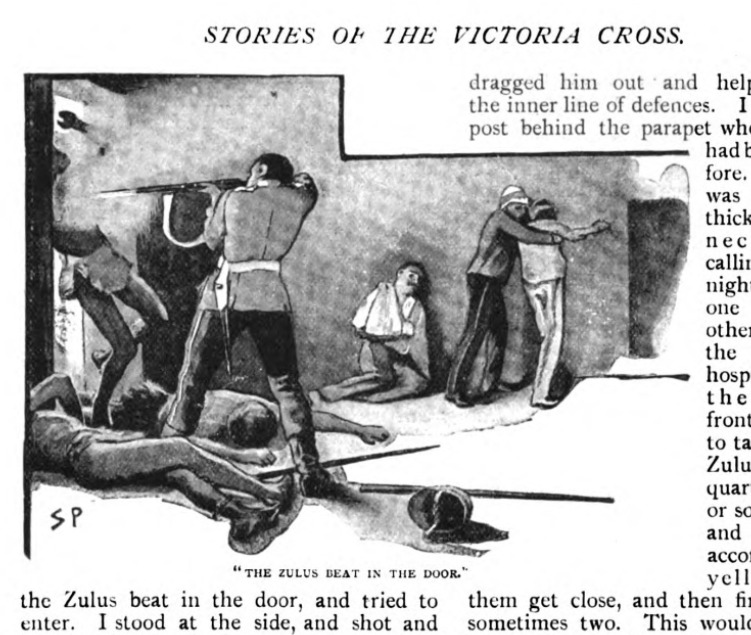

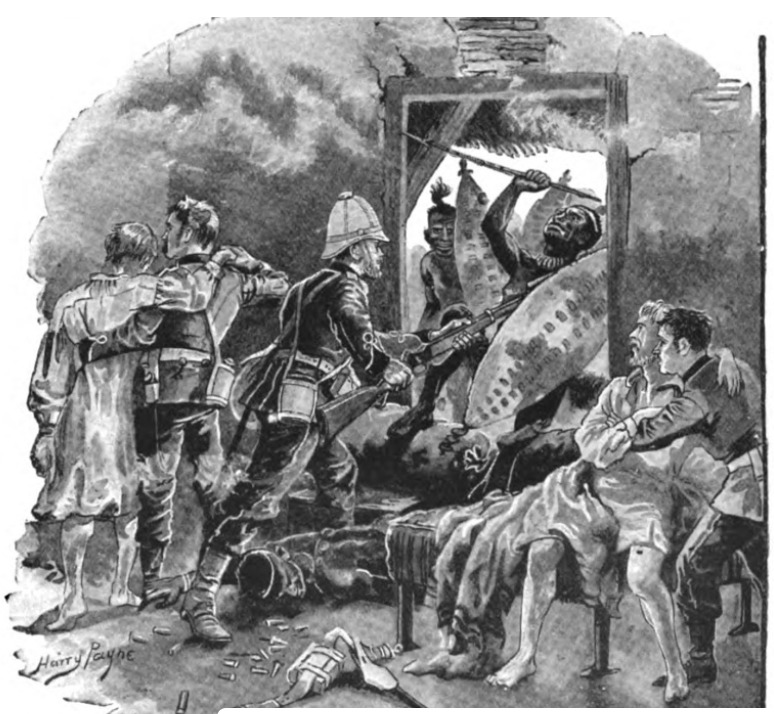

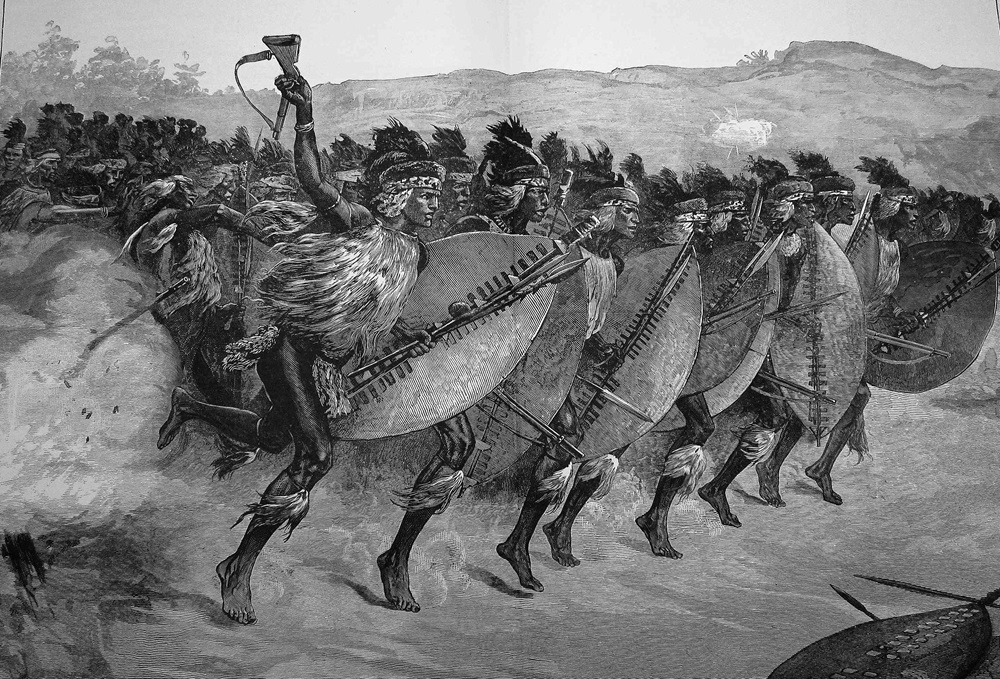

It is noticeable, however, that most of the movement is ascribed to the Zulus. In a practical sense this reflects the fact that one army was attacking and one defending, with the British presenting a phalanx of rifles and the Zulus running at the lines. But movement as deployed in this context also has a racial dimension and is used to differentiate between the White British and their Black enemies. According to this racist formulation the Zulus’ dynamism is a sign of brutal savagery. ‘Stamping’ and ‘raving,’ as Dickens has it, suggests their desire to be ‘killing incessantly’ (338), while the relative stillness of the British connotes, once again, their steadfast determination, as civilized men, to act with dignity and valour. This contrast, between civilized orderliness and uncivilized disorder, can be traced in detail. It appears in The Strand’s (1891) representation of the hand-to-hand fighting in the hospital block at Rorke’s Drift, and it features in the paintings.

Two scenes from The Strand’s article on the Anglo-Zulu war, which reports the testimonies of two of the soldiers, Hook and Williams, who fought the Zulus at Rorke’s Drift.

William Henry Dugan’s painting of The Siege of Rorke’s Drift (1879, Royal Welsh Museum, Brecon) exemplifies this opposition of still/moving, with the British soldiers blocked into the right half of the composition and the Zulus positioned to the left: the attackers are a mass of writhing figures, with one Zulu jumping into the British enclave, while the defenders are positioned within a compact line of differentiated and relatively static individuals. The dramatic difference between the two sets of combatants is enhanced, moreover, by the artist’s deployment of a linear contrast: the British are placed within a single, static arc, while the Zulus are positioned as part of a convulsive arabesque that reaches from the background and spills, like an unravelling spring, into the middle and foreground. Energy and stillness are thus presented in counterpoint, with the contrast of movement and disciplined stillness being exemplified in the painting’s formal arrangement. Indeed, the line defining the British zone prevents the rhythmic, Zulu line from moving left to right, containing the energy, we might say, just as the 42nd Foot contained and deflected their adversaries in the battlefield at Rorke’s Drift.

Charles Fripp’s monumental painting of The Battle of Isandlwana (1885).

This contrast is further marked in Fripp’s The Battle of Isandlwana (1885), which overwhelmingly promotes an iconography of resolution in the face of chaotic violence and disorder. Fripp shows the final moments when the British contingent has been reduced to a few men who stand shoulder to shoulder, entirely surrounded by a vast swirl of enemy figures. It is probably an accurate depiction, but Fripp accentuates the difference between the static British and the broken outlines of the Zulus’ raised arms; the Zulus are chaos, the British the still centre of swirling arabesques. Their positioning against the distinctive mountain is also significant. Not only a piece of geographical verisimilitude, the landmark acts metaphorically to suggest that the British are as fixed and unchanging as rock as they face the ever-changing chaos of their adversaries; ironically, the landscape of Natal becomes a signifier of the strength of its invaders. The battle was desperate, but despite the outcome Fripp makes sure that White superiority is embodied in his painting’s compositional arrangement and symbolism. It seems as if the British have won, despite the outcome.

But Fripp’s visual propaganda did not convince the public. A large audience flocked to see Butler’s, Neuville’s and Dugan’s works when they were exhibited, but few wanted to view a depiction of the defeat at Isandlwana. Fripp’s painting tried to assert Britishness, but the painting was viewed purely as an unpalatable reminder of a notorious failure.

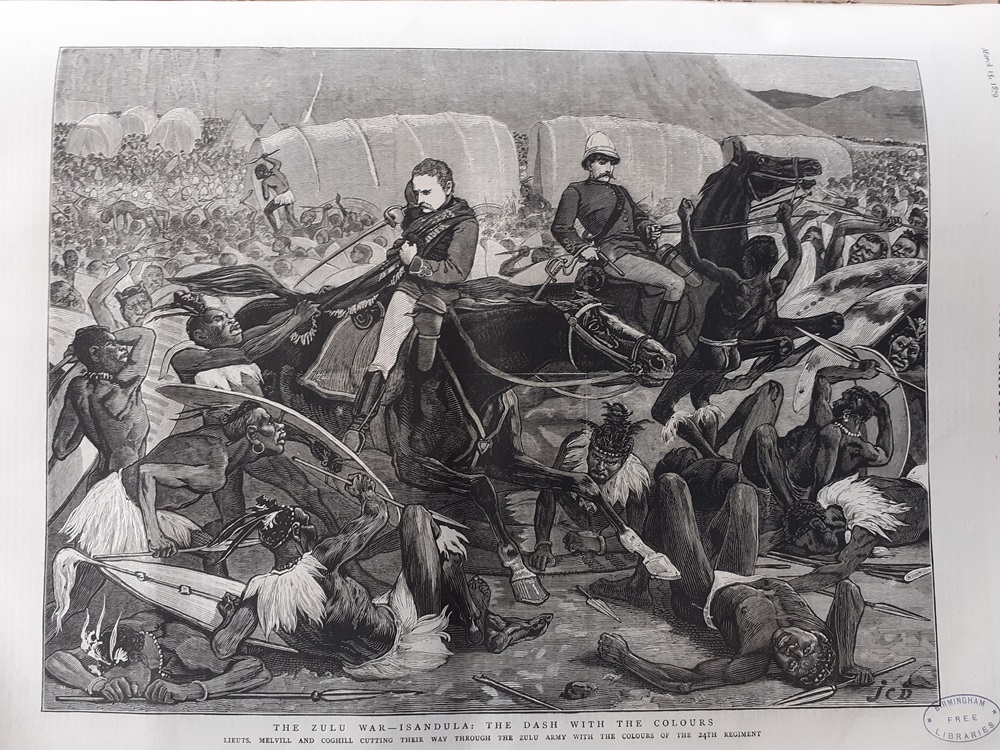

Left: A representation of Coghill and Melvill’s desperate attempt to save the colours at Isandlwana, surrounded and cut down by a horde of milling Zulus; and Right: the Zulus running into battle.

The incapacity of the British to cope with the Zulus at their most dynamic also informs the many representations in the illustrated press which constantly stress the Zulus’ movement. Throughout the pages of The Illustrated London News and The Graphic the viewer is presented with a dynamic spectacle in which the Africans run into battle or overwhelm the British enemy; figured as large and impressive wood engravings, typically printed over a double spread, these images vividly convey the notion of the Zulus as a sort of force of nature – a flow energized by dynamic bodies in which the British military can only respond with the strictest discipline and orderliness.

Art as Spectacle

Political and racial attitudes inform the visual responses to the Anglo-Zulu war, but images of the conflict also acted as entertaining spectacles. Within this discourse two elements came to the fore: one was the emphasis on large and alien landscapes, and the other the aerial representation of battles.

The Illustrated London News contains several engravings of panoramic topographical scenes where the main engagements were fought, and presented a detailed visual geography for consumers at home. In each case, the emphasis is on the vast scale of the landscape, so stressing its foreign nature and the epic task of subjecting it to imperial control. The same could be said of painted responses, particularly the vast panoramic work by Adolphe Yvon, The Battle of Ulundi (1880), which though painted by a French artist is very much in line with the visual conventions of Victorian art.

Adolphe YvonThe Battle of Ulundi (1885).

This image is one of several that deploy a bird’s eye view to represent the essential information and suggest that the subjects are being shown with journalistic objectivity, even though the artist was not present at the scene and can only surmise on how the situation unfolded.

Nor can it can be said that the landscapes are presented objectively. Instead of being presented in purely topographical terms, the vast terrains of the Natal are romanticised, as places of seemingly endless perspectives that lead into an indeterminate distance and are dominated by vast mountains and ridges. This understanding invokes the wonder of the imperial experience, as audiences at home were presented with landscapes that were as unknown and inexplicable as the cultures Britain sought to conquer.

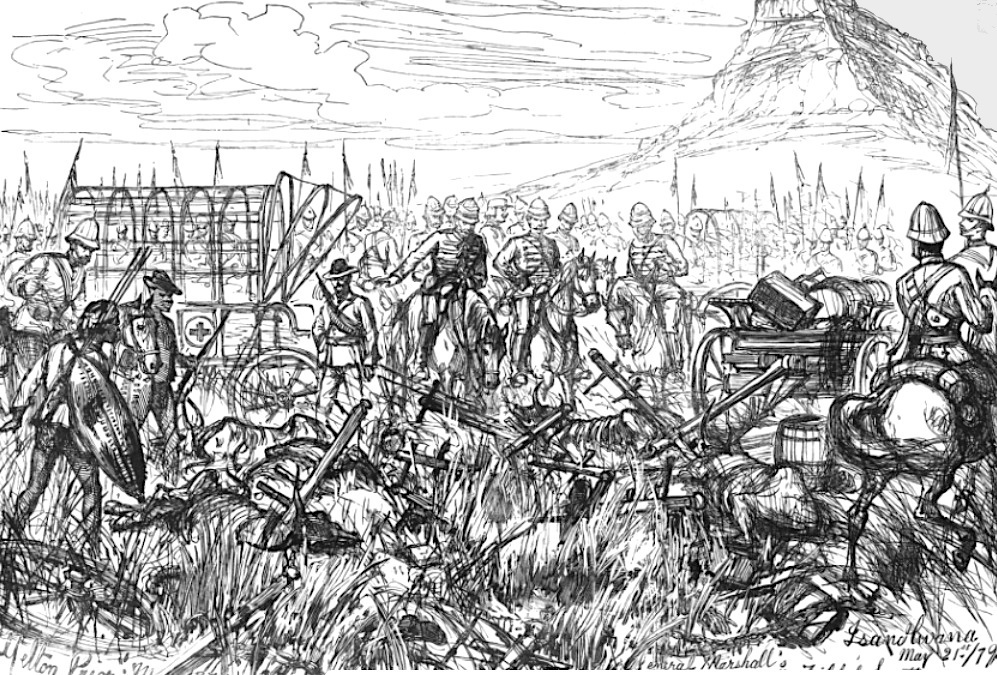

Perhaps the only journalistic images are those representing Isandlwana after the massacre. These show the deserted field occupied only by burnt-out wreckage. For example, Melton Prior’s design in The Illustrated London News depicts the aftermath in existential terms, presenting his drawing in sketchy lines as a melee of broken lances and indeterminate forms. In contrast to the paintings, this image is far from heroic and evokes a melancholy despair.

Prior’s reflection on the aftermath of Isundlwana

‘Despise not your enemy’: Changing Attitudes to the Zulus

The artists’ differentiation of movement/stillness is informed by a racist perception of Britain’s enemies and places the Zulus within the Victorian taxonomy in which Whites (especially the British) are positioned at the apex of human development, and all those of colour in a subordinate position. This notion is exemplified by the pictorial frontispiece for volume one of J. G. Wood’s The Uncivilized Races of the World (1872) in which the White ruler is shown as an idealized, paternalistic type as he speaks with God-like authority to his savage subjects.

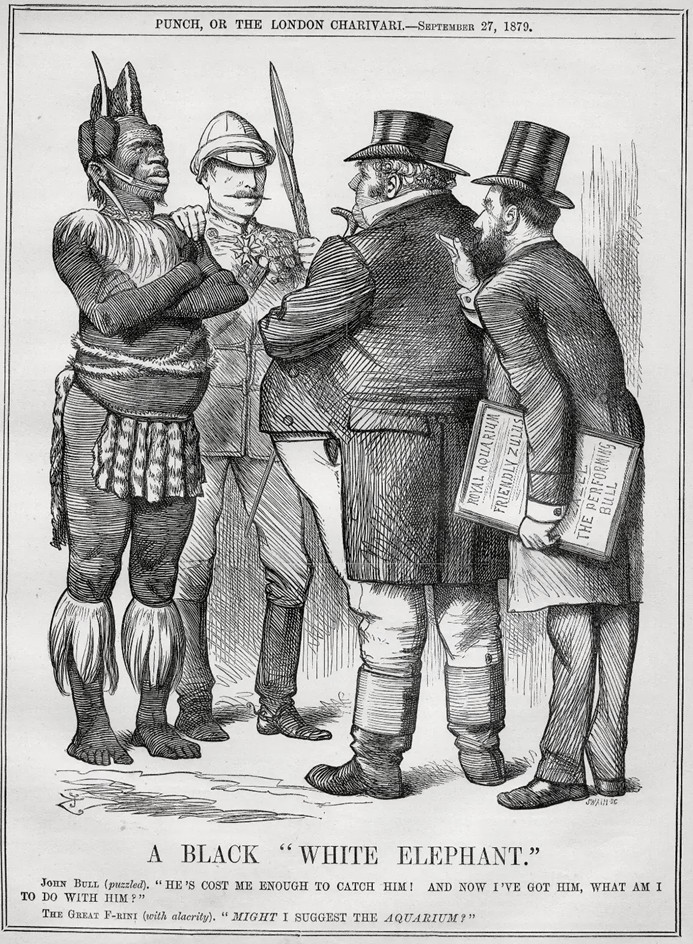

The Zulus, especially, were widely believed to be uncivilized, devoid of human feeling, and (in some quarters) barely human at all. This judgement is typified by David Leslie in his account of life in Among the Zulus (1875). Such people, he says, ‘have no idea of morality whatever’ (3), are lazy, and as cruel and unfeeling as ‘dogs’ (202). Near animals themselves, they were said to defy the improving hand of the missionary and any attempts to impose (White) civilization, and, another commentator remarks, may even try to impose their values on the European colonizers (Creswick 38). At best, the Zulu was an anthropological specimen, an extreme position exemplified by ‘The Great Farini’s’ ‘human zoos’ of the 1870s, in which ‘friendly Zulus’ were exhibited as a sort of circus act. Such negative attitudes were long established.

Dickens took a typical view (1853) when he wrote ironically of the ‘Noble Savage.’ The author went to look at some Zulus when they were displayed at St George’s Gallery in London and found them ‘extremely ugly’ – if not as ugly as some other Blacks – and thoroughly ‘odiferous.’ For him, as for so many, the Zulu was a barbarian, an animal that emitted ‘screeches, whistles, and yells’ and could only be viewed as ‘diabolical’ (338).

One of Tenniel’s racist cartoons in Punch.

There is a strong sense of this ‘diabolical’ energy in the visual treatment of the Zulus’ dynamism, and we might expect them to be presented as racist caricatures, given that mockery of foreigners was commonplace in nineteenth-century society, as in Richard Doyle’s An Overland Journey to the Great Exhibition (1851) and Robert Cruikshank’s Comic Album (1834), which shows Blacks in crude cartoonish imagery as murderous and stupid.

Yet, and bearing in mind these racist beliefs, it was often the case that Zulus’ bodies and faces were treated sympathetically. Indeed, visual interpreters engaged with what was an emerging ambivalence in attitudes: the Zulus might be viewed as barbarous and without mercy, but their military prowess, having beaten the most powerful army in the world, was worthy of respect. Such ‘savage frenzy,’ as one commentator remarked, could be seen as both terrifying and impressive (‘The Defence of Rorke’s Drift,’ 2).

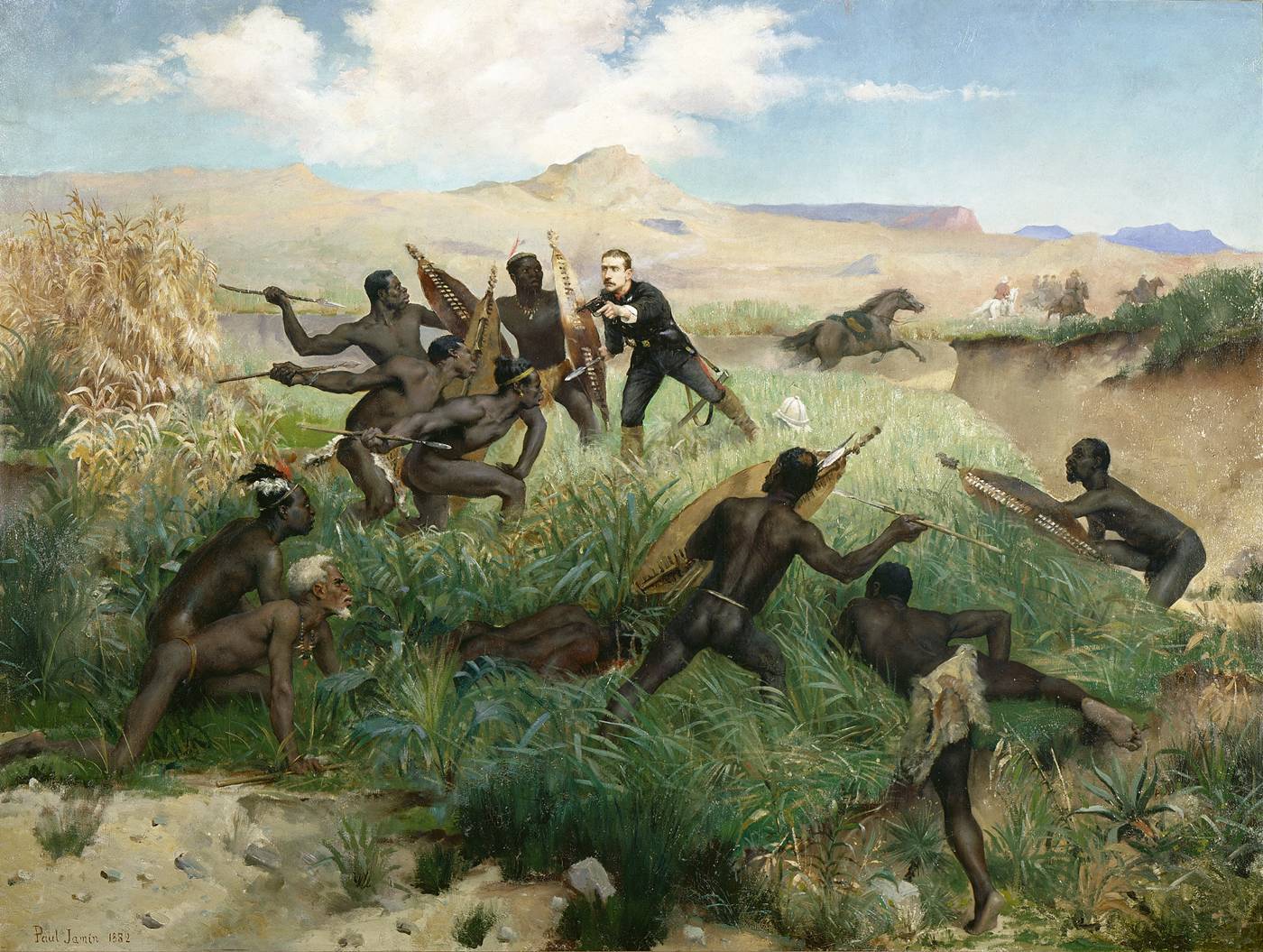

Paul Joseph Jamin, Mort du Prince Imperial ou Zoulouland (1882).

This begrudging admiration found expression in images such as Paul Joseph Jamin’s treatment of the moment when Louis, the Prince Imperial, who had a position within the British Army, was killed in a skirmish (Collection of Château de Compèigne, France). The event shocked Britain and all of Europe, but Jamin shows his killers not as bestial assassins, as one might expect, but as idealized, athletic types. Their faces are similarly treated with respect, with no sign of caricatural exaggeration, and although produced by a French artist the approach is in accordance with British attitudes. An anonymous representation of a Zulu Scout in The Illustrated London News is similarly respectful: the intent eyes and expression connote intelligence, and the inclusion of a bullet-belt and rifle align the character with the imperial White man. Cast in these terms, the Zulu had to be respected because he was seen as just another empire builder, a mirror of British imperialism, and one to be taken seriously.

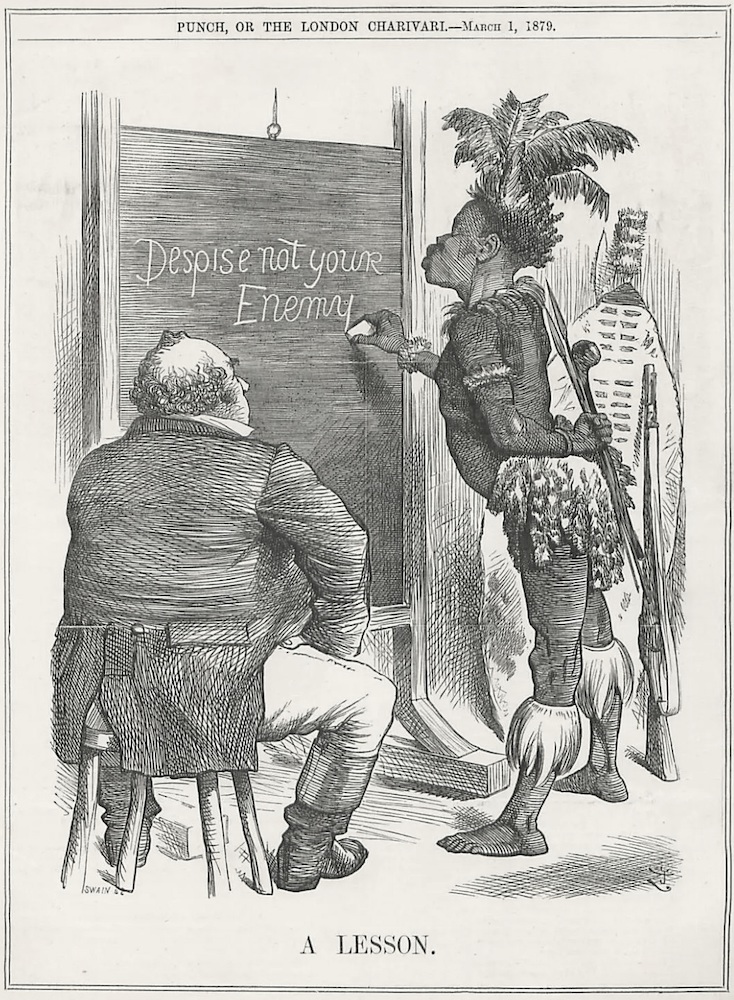

Left: an anonymous portrait of one of the Zulu scouts whose effectiveness wrought havoc with the British contingent; and Right: Tenniel’s penetrating view of British complacency and the need to learn.

The need for respect was given its clearest expression, however, in Tenniel’s Punch cartoon, A Lesson. Published on the first of March 1879, just over a week after the disaster at Isandlwana and the defence of Rorke’s Drift, Tenniel’s design spells out the need for Britain to learn from the enemy, and to regard that enemy with the esteem that should be accorded by a student to a teacher. John Bull, the emblem of Britain, is represented as a pupil sitting on a classroom stool, while the instructor writes up the lesson to be learned: ‘Despise not your enemy.’ The humour is grimly accentuated by the Zulu’s confident stance, holding a club and shortened spears or iklwa behind his back rather than his schoolteacher’s cane, and the message is unambiguous and hard-hitting: fail to learn, and you will be punished – again. At Ulundi that lesson was learned, and as a result the British won the war.

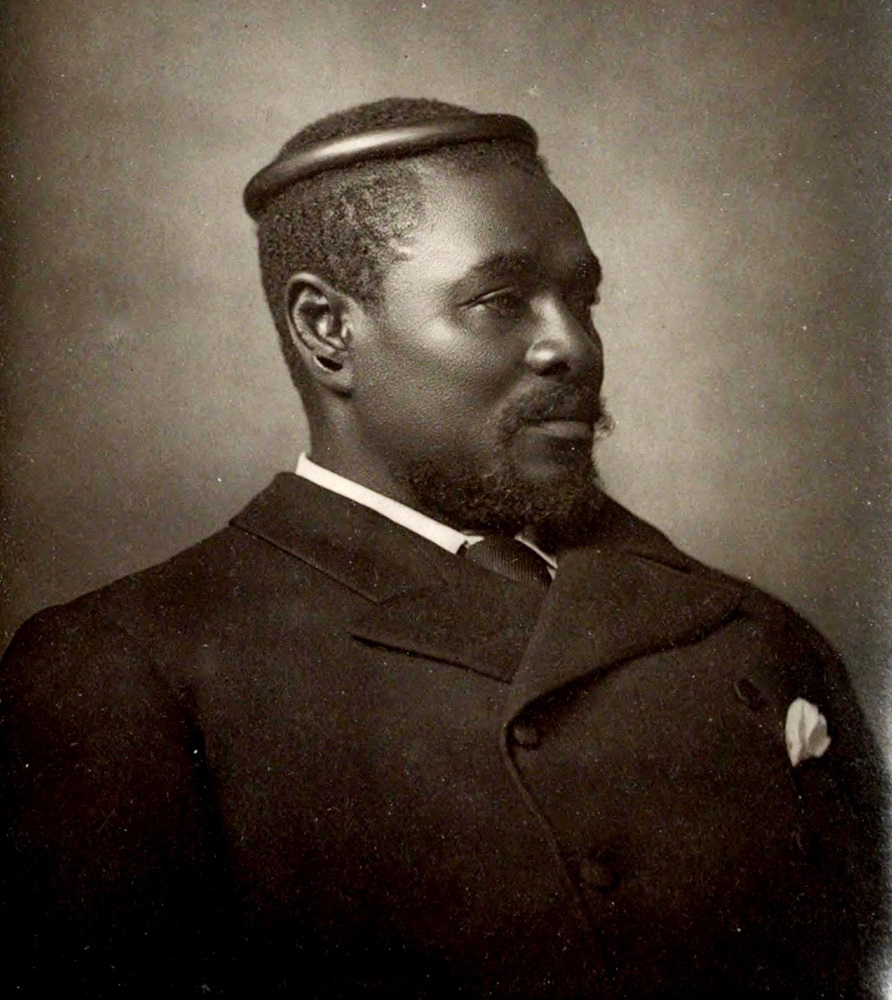

A photograph of Cetawayo which stresses,

his handsome masculinity.

The Victorian image-makers of the Zulu war thus participated in this process of mediation, and contributed to the idea that the British had to acknowledge when they had been bettered by a superior adversary. In fact, later Victorian culture shows a marked change in attitudes. When Cetawayo visited in 1882, and met the Queen, his hosts were impressed and could only accept, as Julie Codell points out, that the king was (almost) an equivalent to the British monarch, finding him ‘no savage cannibal, but a courteous, amiable, and smiling gentleman’ (413). Cartoons in Punch reflected this change, and the savage who had ordered the destruction of the British in Natal became the subject of an heroic portrait by Carl Rudolph Sohn. The work, tellingly, was commissioned by an appreciative Victoria. Photographs similarly stressed Cetawayo’s handsome physiognomy, a visual manoeuvre that aligned him with the British heroes he had so ferociously defied. This, however, was not the end of the Zulu narrative, which continued to develop into modern times.

Revisiting the Anglo-Zulu War in Film

As we have seen, Victorian visualization of the Anglo-Zulu war closely reflects contemporary attitudes to empire, masculinity, and racial otherness. Isandlwana was quietly forgotten, but Rorke’s Drift was mythologized to become a lasting symbol of British resilience. Both battles were to be re-considered in the films Zulu (1964), directed by Cy Endfield, and Zulu Dawn (1979, Douglas Hickox). Each of these embodies an interpretation of events that reflects and revises the Victorians’ writing of the Zulu narrative.

In Zulu, the more accomplished and complex of the two films, Endfield offers a complicated meditation on class, power, race, and heroism. Chard and Bromhead (played by Stanley Baker and Michael Caine) are shown not as heroic types in the manner of Victorian iconography, but self-doubting and troubled: their relationship is riven by class tensions, they are terrified by the threat they face, and squabble about how best to survive and who should take command. Working with a script written by Endfield and John Prebble, the two leads offer nuanced performances which subvert the stereotypes of Chard and Bromhead as iron-willed heroes, replacing the iconic images in Butler’s and Neuville’s paintings with what are ultimately agitated, exhausted, bloodied and self-doubting figures, no different from the desperate men they command.

Endfield’s reworking also reflects modern changes in racial attitudes. The Victorian audience only came to respect the Zulus once they had demonstrated their military abilities, but in Zulu the enemy is immediately presented as a worthy opponent. Though shot in the Apartheid period in South Africa, with interactions between the Zulu extras and the British cast being strictly controlled by the police (Hall 181–82), the film asserts a respectful attitude to those who were reenacting their ancestors’ military campaign. There are, in fact, numerous examples of the affirmation of the Zulus as an impressive military threat and they are consistently figured as members of a nation that was far from insignificant or contemptible. The opening, travelling shot is of the massacre at Isandlwana, so establishing their power, and there are several occasions when disparagement of the Africans is immediately contradicted. One soldier speculates that the Zulus are ‘just a bunch of savages,’ but the character of Schiess (played by Dickie Owen) angrily explains how they can run ‘twenty miles in a day’, far more than the British can manage; Bromhead’s contempt is likewise modified by the Boer Lieutenant Adendorff (Gert van den Bergh), who explains the Zulus’ highly effective military strategies; and the long opening sequence of the Zulus’ marriage celebrations – 10 minutes in a running time of 2 hours, 18 minutes – is a rich celebration of the strength and complexity of the Zulus’ culture. Tellingly, the Zulus’ joyful and dynamic dancing and singing are placed before we are introduced to life at Rorke’s Drift, and Enfield pointedly contrasts the splendour of the Zulus’ rituals with the slovenly laziness of the soldiers (who are idling while Chard is working to supervise the building of a bridge); he also shows the arrogance of Bromhead as he too idles away his time shooting game, only finding time to mock Chard’s making of ‘mud pies’ in the river.

Top: Paul Dade’s cinematic visualization of the Zulus’ marriage ceremony; and Bottom: Bromhead enjoying his leisure time.

From the start the Zulus are set up to impress, and this sympathetic treatment is especially demonstrated in their attacks, which show them to be both courageous and tireless. If the initial engagement seems to go in the defenders’ favour, it is countermanded by the Adendorff’s remark that the Zulus were simply assessing the regiment’s firepower as they respond to their generals’ directions. Indeed, the cinematographer, Stephen Dade, creates visual compositions which repeatedly stress the Zulu’s military agency: their first appearance, as a vast line on the crest of a hill, is emphasised by a seemingly endless pan – shot in 70 mm lenses and creating an image twice the usual width of a Cinemascope frame on the screen – that embodies their menace in an overpowering visual form; the travelling shots ‘run’ with the Zulus as they attack, so emphasising their unstoppable dynamism; the main assaults are bloodily relentless; and despite the practice of volley-fire the stockade is repeatedly overrun, with close editing being used to express the chaotic immediacy of each moment. The courage of the British is more than matched by the bravery of the Zulus, and the film’s visual style, running in tandem with verbal information, is a clear representation of the Africans’ power.

The Zulus’ power is expressed visually in a powerful linkage of landscape and manpower, vividly conveyed in a seemingly endless pan-shot which shows the Zulus mustering on a hill-top. John Barry’s musical score adds to the regiment’s awe – and despair.

Always, the British and Zulus are shown as being of equal stature as warrior-races, each with their own command structure and strategies. The social rituals of the Zulus are likewise represented in visual counterpoint and equivalence to those of the British. The connection and symmetry between the two is especially embodied in the cinematography, an interplay exemplified by the intercut sequence when the British sing ‘Men of Harlech’ and the Zulus’ reply with a song of their own. Both camps are visualized in sinuous travelling shots which rhyme with each other, creating a parallelism that stresses the lack of difference between them. The Zulus’ singing of a tribute song when they cannot defeat the British is a final touch – an event which did not happen in reality but symbolizes the respect that both combatants ultimately felt for each other.

Top and bottom: two shots from an intercut sequence in which the enemies sing to each other – singing songs that are both defiant and auditory signs of kinship between comrades-in-arms.

Endfield’s film conveys the recognition in Victorian society that the Zulus were an heroic adversary, and the overall effect of his work, despite his demonstration of the horrors of violence, is celebratory, and values courage on both sides. Endfield’s interpretation of events also recognizes that the survival of the British was distorted into a myth by the authorities, with Bromhead noting early in the narrative that the battle will be domesticated and become a propaganda tale for ladies at home – exactly the sort who might read The Penny Illustrated Newspaper. At the same time, Endfield registers a modern disapproval of the iniquity of the violence generated by British imperialism. At the end of the film Bromhead reveals that he feels ‘ashamed’ by the mass killing of the Zulus, a comment matched by Chard’s dislike of what he calls a ‘butcher’s yard’ of slaughter. Their attitudes are almost certainly anachronistic, but they match the film’s generally left-wing approach to class, imperialism and racial conflict. Endfield was one of the talented American directors who were forced to leave America by the McCarthy hearings under suspicion of having Communist affiliations, and in all of his films, especially Zulu, he adopts an anti-authoritarian, humanistic approach to his subject-matter. Not quite a 'radical' when placed in a British context, Endfield interrogates his material, provides a sober assessment of the Zulu conflict and rigorously avoids the cliches of jingoism and sentimentalized heroism.

If Zulu engages with racial issues and the need for mutual respect, Douglas Hickox’s Zulu Dawn (1979), which was also written by Enfield, points to the many failures that led to disaster at Isandlwana and is a faithful reflection of nineteenth-century commentary on the incompetence of the commanders. In particular, Hickox focuses on the complacency of Lord Chelmsford (Peter O’Toole) and the indecisiveness of the camp’s officer, H. B. Pulleine (Denholm Elliot). Chelmsford is shown to be thoroughly inept and brutally overbearing, with poor relationships with his men and a fatal unawareness of the Zulus’ threat. When he should have been making preparations to defend the camp, for example, he is shown taking tea and sandwiches with his officers, a scene that incongruously invokes the rituals of home and in so doing reveals his intellectual limitations. O’Toole’s frosty, clipped delivery adds to this effect and defines Chelmsford as a man fatally alienated him from the men and officers he should be directing –and protecting.

Taking up on the theme of social tension in Zulu, Zulu Dawn can in this sense be viewed as a satire of the uselessness of the commanding upper classes and the need for the army to be led by professionals rather than the merely privileged. One historian writing in 1900 comments on Chelmsford’s ‘military incapacity’ (Willson 4, 564) and Zulu Dawn makes it clear that his leaving of the camp with insufficient means to protect itself was a disastrous error.

Zulu Dawn is also notable for its brutally truthful representation of the battle. The Zulu army is gigantic, viewed as a seething mass through Ousam Rawi’s panoramic shots, and the violence itself is more visceral than it is in Zulu. The film entirely contradicts Fripp’s idealized imagery in his painting of the soldiers as a phalanx of grim-faced heroes, showing them, instead, as the victims of an onslaught which destroys the regiment in ways both horrifying and pathetic. Hiscox further represents in anti-heroic terms the attempts of Lts. Melvill and Coghill to ride off with the colours. This break-out was presented in several heroic prints and illustrations; in the film, though, their frantic effort to escape is shown as just another act of desperation. Both are shown with brutal directness when they have been killed, an image that is far from patriotic or celebratory.

These films act, in short, to interrogate aspects of the Anglo-Zulu war and its most memorable engagements, asserting truths which both confirm and expand Victorian understandings of the conflicts. Taken as a whole, visual interpretations have played an important role in mediating the complexities of the war and attitudes towards it. Visualized by Victorian and modern artists, the Anglo-Zulu war continues to resonate.

Bibliography

Primary

Cruikshank, Robert. The Comic Almanack. London: Kidd [1834].

Doyle, Richard. An Overland Journey to the Great Exhibition. London: Chapman & Hall, 1851.

Enfield, Cyril (Cy). Zulu. Paramount Pictures, 1964.

The Graphic Illustrated Newspaper (1879).

Hickox, Douglas. Zulu Dawn. Orion/Warner. 1979.

The Illustrated London News (1879).

The Illustrated Penny Newspaper (1879).

Punch (1879).

The Strand 1 (1879).

Tennyson, Alfred. Poems and Plays. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1983.

The Western Daily Mail (1879).

Wood, J. G. The Uncivilized Races. 2 Vols. Hartford: Burr, 1872.

Secondary

Butler, Elizabeth. An Autobiography. London: Constable, 1922.

Codell, Julie. ‘Imperial Differences and Culture Clashes in Victorian Periodicals: The Case of Punch.’ Victorian Periodicals Review 39, no. 4 (Winter 2006): 410–28.

Cowling, Mary. The Artist as Anthropologist: The Representation of Type and Character in Victorian Art. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

Creswick, Louis.South Africa and the Transvaal War. Vol. 1. Edinburgh: Jack, 1900.

‘The Defence of Rorke’s Drift.’ Freeman’s Journal (19 March 1880): 2.

Dickens, Charles. ‘The Noble Savage.’ Household Words (11 June 1853): 337 –339.

Hall, Sheldon. Zulu: with Some Guts Behind It. Sheffield: Tomahawk Press, 2005.

Knight, Ian. Nothing Remains but to Fight: The Defence of Rorke’s Drift, 1879. London: BCA, 1993.

Leslie, David. Among the Zulus. Glasgow: Private Circulation, 1875.

Lucas, Thomas J. The Zulus and the British Frontiers. London: Chapman & Hall, 1879.

Wells, Samuel Roberts. Phenology and Physiognomy. New York: Samuel Roberts Well, 1876.

Wilson, Robert. The Life and Times of Queen Victoria. Vol. 4. London: Cassell, 1900.

Created 15 March 2025