Photographs by the author. You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.

Isandlwana in 1992 with British grave cairns in the foreground

Fugitives’ Drift on the Buffalo River in South Africa is the ford where the survivors crossed on 22nd January 1879 in their desperate escape from the massacre at Isandlwana. In that battle part of a British invading force was annihilated at the hands of the Zulus with nearly 1800 killed and only 55 surviving. It was one of the biggest disasters in British Imperial history. In 1879 the drift was called Sothondozo’s Drift but is now best known as the place where Lieutenant Teignmouth Melvill, carrying the Queen’s Colour of the 1st Battalion of the 24th Regiment and Lieutenant Nevill Coghill also of the 24th lost their lives. The scene was recreated (with some poetic licence) in the film “Zulu Dawn”.

In 1992 I stayed at the nearby Fugitives’ Drift Lodge and visited Melvill and Coghill’s graves after dinner by torchlight in the company of David Rattray, who owned the Lodge, and the historian Ian Knight. According to his Daily Telegraph obituary “David Rattray was a self-taught historian. In the 1960s his father had bought 10,000 acres of bush on the banks of the Buffalo River, including the ford (or drift) across which most of the British survivors of Isandlwana fled. Young David visited during his school holidays, learning Zulu and listening to the stories of a local tribal chief whose father had fought in the battle”. Knight, who would later publish a string of books on the Zulu War, became the global expert on the conflict.

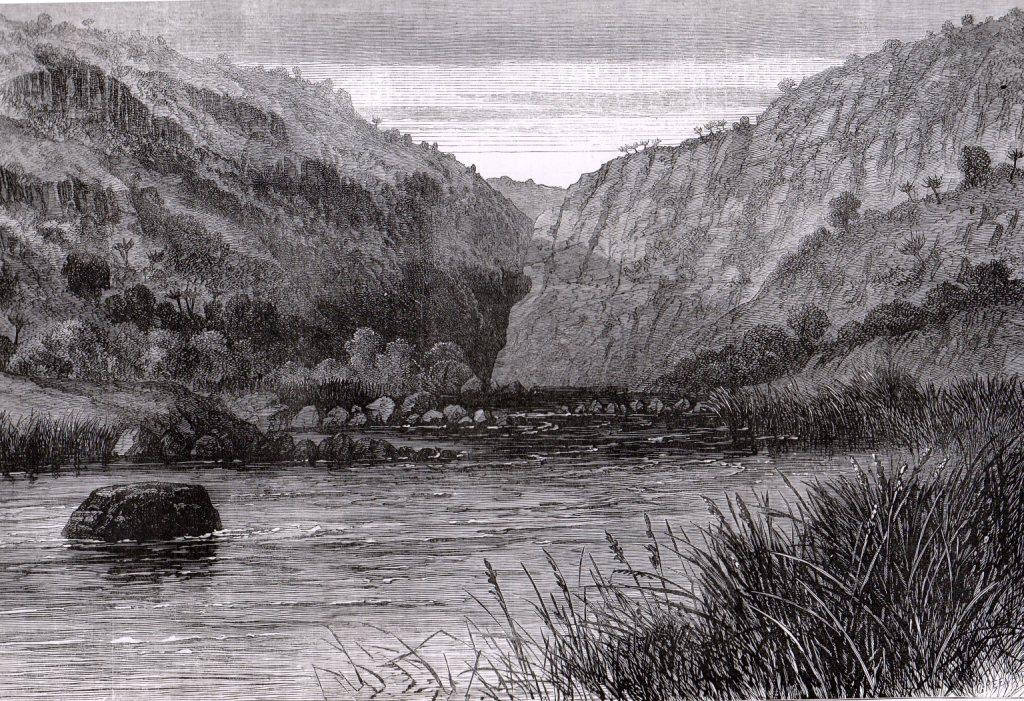

Left: The grave of Melvill and Coghill at Fugitives'Drift. Right: Melvill's Rock in the Buffalo River from the “Illustrated London News’. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

An abridged version of Rattray’s account of the flight from Isandlwana reads as follows; “In the closing stages of the fight at Isandlwana, Colonel Pulleine apparently entrusted Lieutenant Melvill, the Adjutant of the 1/24th, with the Queen’s Colour. With the heavy, furled and cased Queen’s Colour, Melvill, on horseback made off across the five miles of boulder-strewn, bush-clad, broken country towards the Buffalo River, joining a number of other fleeing horsemen.

Left: Lt N J A Coghill. Right: Lt Teignmouth Melvill. Courtesy of The Regimental Museum of The Royal Welsh, Brecon. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

No-one will ever know what a terrible ride that must have been for Melvill, encumbered by that heavy Colour. That he made it to the river, in itself constitutes a miracle. He plunged his horse into the water and, clinging to the Colour rather than to his horse, was almost immediately separated from his mount. He was helped onto a large coffin-shaped rock that was just breaking the surface by Lieutenant Walter Higginson. The Zulus began pelting them with spears and firing at them with their muskets.

Lieutenant Coghill had in the meantime successfully forded the river and was on the Natal bank slightly downstream from Melvill. Sometime prior to Isandlwana, Coghill had seriously injured his knee. He now found himself in the saddle of his horse on the Natal bank with a fairly clear run [for safety] in front of him, when he turned and saw Melvill in the river clinging to the rock with the Queen’s Colour. This sight stimulated him to perform his great act of courage: he put his horse back into the flooded river in order to save his friend and the Colour. A warrior on the Zulu bank fired a shot which struck Coghill’s horse and killed it, pitching Coghill into the stream. Undaunted he swam on, reaching the rock to which Melvill and Higginson still clung. The three officers decided to swim for it. In the rapids below the pool they were tossed over rocks and boulders, and despite their most desperate efforts, the Colour was swept from their grasp, whirled away downstream and was lost.

Melvill, Coghill and Higginson fetched up on the Natal bank. Melvill was exhausted to the point of being immobile and Coghill was unable to walk because of his bad knee. Higginson volunteered to climb up to the lip of the gorge on the Natal side to look for horses of which there were apparently a number that had lost their riders in crossing the river. From an escarpment above the gorge Higginson witnessed the demise of the other two officers. Melvill had apparently recovered sufficiently to drag and carry Coghill up out of the gorge. Melvill and Coghill staggered up the little path that ran through the cleft at the top of the valley and flopped down, exhausted, against a large rock. In a few moments of flashing spears both these fine, brave men were dead.

The Buffalo River from Melvill and Coghill's grave

Another escapee that afternoon was Horace Smith-Dorrien who would later become a famous First World War General. He observed

I heard afterwards that [the Zulus] had been told by their King Cetywayo that black coats were civilians and were not worth killing. I had a blue patrol jacket on, and it is noticeable that the only five officers who escaped....had blue coats. I rode through unheeded, and shortly after was passed by Lieutenant Coghill, wearing a blue patrol and cord breeches and riding a red roan horse. We had just exchanged remarks about the terrible disaster, and he passed on towards Fugitives' Drift. The ground was terribly bad going, all rocks and boulders, and it was about three or four miles from camp to Fugitives' Drift. When approaching this Drift, and at least half a mile behind Coghill, Lieutenant Melvill, in a red coat and with a cased Colour across the front of his saddle, passed me going to the Drift. It will thus be seen that Coghill and Melvill did not escape together with the Colour.

The Queen's Colour of the 1st bn of the 24th which was briefly lost in the Buffalo River. Courtesy of The Regimental Museum of The Royal Welsh, Brecon.

The loss of the Queen’s Colour was a major humiliation for the 24th Regiment and so it was with great relief when on 4th February 1879 it was found in the river and restored to the 1st Battalion. Its other flag, the Regimental Colour had been left in safety at Helpmekaar. However the 2nd Battalion of the Regiment lost both its Queen’s and Regimental Colours at Isandlwana although some parts (but not the flags themselves) were later recovered. All these relics are now in Brecon Cathedral in South Wales.

In 1879 the Victoria Cross was not awarded posthumously, and so the London Gazette published a Memorandum as follows: “2nd May 1879. Lieutenant Melville [sic], of the 1st Battalion 24th Foot, on account of the gallant efforts made by him to save the Queen's Colour of his Regiment after the disaster at Isandlwana, and also Lieutenant Coghill, 1st Battalion 24th Foot,-on account of his heroic conduct in endeavouring-to save his brother officer's life, would have been recommended to Her Majesty for the Victoria Cross had they survived.” Policy changed after the Boer War and VCs were duly awarded to both men, announced again in the London Gazette. “War Office, January 15, 1907. The King has been graciously pleased to approve of the Decoration of the Victoria Cross being delivered to the representatives of the undermentioned Officers and men who fell in the performance of acts of valour, and with reference to whom it was notified in the London Gazette that they would have been recommended to Her late Majesty for the Victoria Cross had they survived:”

Field Marshal Viscount Wolseley. From a photograph by Lafayette of Dublin.

Sad to relate, however, the awards were not without controversy. One of the heavyweights of the Victorian military establishment General Sir Garnet Wolseley commented

I am sorry that both of these officers were not killed with their men at Isandlwana instead of where they were. I don't like the idea of officers escaping on horseback when their men on foot are killed. Heroes have been made of men like Melville and Coghill, who, taking advantage of their having horses, bolted from the scene of the action to save their lives, it is monstrous making heroes of those who saved or attempted to save their lives by bolting or of those who, shut up in buildings at Rorke's Drift, could not bolt, and fought like rats for their lives which they could not otherwise save.

But Melvill would hardly have carried the heavy Colours if his only motivation was to save his skin. And Coghill, who possibly had less justification for his departure from the battlefield, nonetheless returned to the river to save his brother officer.

Smith-Dorrien, who had also saved a man at Fugitives’ Drift but had not received the VC, writing after the Great War, ruefully acknowledged that he did not deserve it. “In view of my latest experiences I am sure that decision was right, for any trivial act of good Samaritanism I may have performed that day would not have earned a M.C. [Military Cross] much less a V.C., amidst the deeds of real heroism performed during the Great War 1914-18.”

Rattray had a remarkable ability for bringing the events alive and he finished that memorable evening in 1992 by telling us how the graves had been desecrated some years earlier with the remains of the two officers clearly visible; one with his boots on and vestiges of their blue and red tunics.

I returned to the site in 2003 but without staying at the Lodge or seeing David Rattray. Tragically he was murdered four years later. According to the Daily Telegraph a six-strong “gang burst into the couple's lodge hotel wielding pistols and rifles at 6pm on Friday [26th January]. One of them shot the renowned historian as he pleaded with them not to harm his wife and a female employee. The raiders fled after the shooting”. His wife, Nicky, later told the Daily Mail “The intruders were just a bunch of bad guys but I don’t believe they set out intending to kill Dave — they just panicked. We had to stop local people from going to their village and burning it down — that shows the depth of anger locally.”

Further reading

Fugitives’ Drift website for David Rattray’s account of Coghill and Melvill’s ordeal.

Knight, Ian. By orders of the Great White Queen. London; Greenhill Books, 1992.

Morris, Donald. The washing of the spears. London; Jonathan Cape, 1965.

Smith-Dorrien, General Sir Horace. Memories of Forty-Eight Years' Service. London; John Murray, 1925.

North East Medals website (for the casualty roll from Isandlwana) http://www.northeastmedals.co.uk/britishguide/zulu/despatch5_isandhlwana_isandlwana_casualty.htm

Royal Welsh Museum Fact Sheet. The Colours; Anglo-Zulu War of 1879. http://royalwelsh.org.uk/downloads/B05-02-24th-Anglo-ZuluwarColour1879.pdf

“Obituary of David Rattray.” The Daily Telegraph. 29th January 2007.

The London Gazette: no. 24717 (2 May 1879): 3178.

The London Gazette no. 27986. (15 January 1907): 325.

“I saw my husband shot dead.” The Mail Online. 7th April 2007.

“General Sir Garnet Wolseley, Commander-in Chief, Southern Africa.” The National Army Museum (6807-386-21).

Last modified 26 March 2016