Was Suicide a Female Malady?

omen were fictionalized and mythologized much as were monsters in Victorian England. They too were made into "others" — weaker vessels or demons, angels in the house or fallen angels (see such fine recent studies as Auerbach, 1982; and Mitchell, 1981) — and suicide was displaced to them much as it was to demonic alter egos. For the most part, fictions about women and suicide became more prevalent and seemed more credible than did facts. The facts themselves were clear: throughout the nineteenth century women consistently had a suicide rate lower than that of men; see especially J. N. Radcliffe, p. 465. Consistent too were the means of suicide. In most cases, women chose poison or drowning over bloodier deaths by gun or knife, a pattern that continues today. These facts were well-established even before mid-century and were well-confirmed after 1858, when William Farr improved record-keeping for cause of death. Lower incidence among women proved, however, easier to determine than to accept. Despite all evidence to the contrary, most Victorians believed what they wished to believe about the frequency of female suicide.

omen were fictionalized and mythologized much as were monsters in Victorian England. They too were made into "others" — weaker vessels or demons, angels in the house or fallen angels (see such fine recent studies as Auerbach, 1982; and Mitchell, 1981) — and suicide was displaced to them much as it was to demonic alter egos. For the most part, fictions about women and suicide became more prevalent and seemed more credible than did facts. The facts themselves were clear: throughout the nineteenth century women consistently had a suicide rate lower than that of men; see especially J. N. Radcliffe, p. 465. Consistent too were the means of suicide. In most cases, women chose poison or drowning over bloodier deaths by gun or knife, a pattern that continues today. These facts were well-established even before mid-century and were well-confirmed after 1858, when William Farr improved record-keeping for cause of death. Lower incidence among women proved, however, easier to determine than to accept. Despite all evidence to the contrary, most Victorians believed what they wished to believe about the frequency of female suicide.

In the main they did so because they wanted and expected suicide, like madness, to be a "female malady." (See Showalter, 1985.) Since women were statistically over-represented among the mentally ill — primarily because in Victorian England they were more often confined to "homes" for the insane and were more easily countable than were men — they were generally thought to be more vulnerable to madness. The reasoning for linking women and suicide went something like this: more women are confined for insanity than men and suicide is a result of insanity; therefore more women should commit suicide than men (see Lewes, 52-78). Or else it went like this: woman is a lesser man, a weaker being, both physically and mentally. Resisting suicide takes willpower and courage; therefore women should fall victim to suicidal impulses far more readily than should men. Unless the weaker sex were to be credited with unwanted strength, the fact that women killed themselves less frequently than men required considerable explaining. Such was the price of retaining the displacement of self-destruction to women in a patriarchal society that was dedicated to championing male mental and physical superiority and to rationalizing sexual differences. [125/126]

The Discrepancy between Statistics and Expectations

Throughout the century, men's explanations for the discrepancy between statistics and expectations centered on what was presumed to be the female disposition. In 1857, writing for the Westminster Review, George Henry Lewes attributed the cause for the lower suicide rate among women to women's "greater timidity" and to "their greater power of passive endurance, both of bodily and mental pain" (71). Lewes was echoed in 1880 by a writer for Blackwood's who asserted that women were "habitually better behaved and quieter; they have more obedience, more resignation, and a stronger directing sentiment of duty.... They possess precisely dispositions of temperament and teaching which best withhold from voluntary death" (727). Female analysts of suicide rates were less likely to make naive pronouncements about female character, but they too felt called upon to explain away the statistics. After observing that "nearly three men commit suicide to one woman," Harriet Martineau concluded that "as there is no such disproportion in the subjects of what we may call natural insanity, we may attribute the majority of male suicides to the habit of men to incur the artificial insanity caused by intemperance" (511). For women's timidity, she simply substituted men's weakness toward another Victorian bête noir, the demon bottle.

At century's end, men like S.A.K. Strahan and Havelock Ellis made less generous conjectures about the female temperament and suicide than had Lewes. Strahan believed that women were weaker contenders in the struggle for existence and therefore less prone to its aftereffects — like suicide. For him, their lower suicide rate depended upon woman's "lack of courage and her natural repugnance to personal violence and disfigurement" (179). Female ignobility, not nobility, marked his suppositions. Ellis's similar judgments hinged less on the rate than on the means of suicide. Referring to what he called the "passive" methods of suicide (drowning, for example), Ellis found women temperamentally irresolute in opting for means that required both less preparation and less gore. More violent forms of suicide offended "against women's sense of propriety and their intense horror of making a mess" and reflected their fear of public scrutiny after they were dead. "If it were possible to find an easy method of suicide by which the body could be entirely disposed of," said Ellis, "there would probably be a considerable increase of suicides among women" (335).

Inherent in these observations is an absurd prejudice in favor of bloodier suicides as being braver and therefore more manly. Ellis makes means of suicide so much a point of honor that he begins to glorify self-destruction and loses sight of his real argument about suicide as a "morbid psychic phenomenon." Inherent here too is a more insidious prejudice [126/127] against women and women's bodies, a male supposition that women must wish to dwindle away to nothing. This is a confirmation of the Victorian ideal of the female self that dissolves into others, much as does Dickens's Esther Summerson in Bleak House. Frances Power Cobbe metaphorically described this ideal as exhibited in marriage. It is as though a male tarantula devours a female spider and incorporates the female wholesale into his own being (789). When the female atomizes into the male, there is simply no longer any "other" to contend with. Cobbe's description can also serve to characterize a state of death-in-life, where there is still a remaining female body, but only a living corpse. In this state, the female's logical end becomes suicide. She is like a child or a mistress who exists but must not be seen, and eventually relinquishes her existence as a confirmation of the way in which she is perceived (for a recent examination of such diminishment see Bassein, ch. 1). The Indian institution of suttee, so fascinating to Victorians, well exemplifies this perception of women. The Englishman Ellis certainly posits something similar in his fanciful alternative to accepting the reality of suicide statistics: rates of self-destruction would be much higher for females if women's bodies could disappear along with their sense of self.

The conjectures of Ellis, the famed pioneer sexologist, help confirm the fact that men displace self-loss in sex to women and therefore displace death to them as well. But Ellis did not really deny the statistics; he only wanted them to be otherwise. It took J. W. Horsley, a prison chaplain in the last quarter of the century, to argue resolutely that suicide was predominantly a female crime. Drawing upon his own experience at Clerkenwell Prison dealing with women rescued from suicide attempts and brought to him for "reform," Horsley became convinced that women had a greater propensity to suicide. They were simply less successful in its execution. He contradicted himself, however, when he suggested how easily such intrinsic female suicide might be prevented: "Hysterical girls make demonstrations on the Embankment, and a pail of water over their finery would often be more efficacious a deterrent or cure than the notoriety they gain (or perhaps seek) by apprehension" (256). Horsley's lack of compassion could hardly have been instrumental in "reforming" Clerkenwell's inmates. He himself asserted that hardly five days at the prison went by without sight of a repeated suicide attempt by a woman. With his own callous attitudes, Horsley seemed determined to help substantiate his belief that suicide was beyond a doubt "a specifically female crime" (241).

Male Displacement of Self-Destruction to Women

Ellis and Horsley show the lengths to which intelligent Victorian men could go to continue displacing self-destruction to women. Taken along with theories of passive endurance, their assumptions lead to the [127/128] heart of a puzzling contradiction. Was women's comparative immunity to the suicidal impulse the result of will-lessness or of willpower? Were women really too weak to commit suicide, or were they morally stronger than men and therefore more courageous in resisting it? If they were simply weak, they better fit Victorian expectations of them. As John Stuart Mill pointed out, women were inculcated to believe "that their ideal of character is the very opposite of that of men, not self-will, and government by self-control, but submission and yielding to the control of others" (27). Such people, sentiment ran, would hardly be bent toward self-destruction, for they lacked the fortitude to kill themselves, much as Ellis and Horsley posited. On the other hand, should they run counter to both statistics and expectation, their inherent weakness was at fault. in either of these cases, they proved baser, lesser beings. But what if they were in fact stronger than men in withstanding suicide? This alternative was by far the more troubling one for Victorians — so troubling that more fallacious reasoning was concocted to explain it away. Argument was diverted from the courage not to die and from the female sense of duty to those "self-willed" women who opted for death. Late in the century, Ellis tried unsuccessfully to prove that the growing number of women whose working lives most resembled men's were more prone to suicide, but he had to admit that women's tendency to suicide versus men's was continually decreasing. Others had been even less generous to women. The famous case of Mary Brough, who slit the throats of her six children and then unsuccessfully tried to kill herself in the same way, raised enormous hostility — more because of Brough's "long-indulged self-will" than because of the child murders. Brough was reported to have been an unfaithful wife who became deranged as a result of her immoral life; her insanity was consequently "self-created" (Winslow, 623) To most Victorians, self-will, Carlyle's first line of defense against suicide, was unnatural in woman — an indication that something was radically wrong. Charles Kingsley, for example, disliked Tennyson's Princess Ida because of her "self-willed and proud longing to unsex herself." She had substituted "her own self-will" for "the womanhood which God [had] given her." As a result she was "all but a vengeful fury, with all of the peculiar faults of a woman and none of the peculiar excellences of man" (250).

Women with willpower struck a different chord with women writers. When Anna Jameson wrote about Cleopatra in her book on Shakespeare's heroines, her imagination thrilled to the "idea of this frail, timid, wayward woman dying with heroism from the mere force of passion and Will" (276). Women also looked askance at the timidity that allowed other women simply to dwindle away to death. In Shirley, , [128/129] Charlotte Brontë's Mary Cave dies by starvation for love and significance rather as the anorectic Nightingale nearly did. Her death may be a suppressed rebellion, but it is clearly cautionary. In this sort of rebellion, the woman dies in order to become noticed or missed. In Shirley, young Caroline Helstone, the love-starved niece, must learn to read Mary Cave's lesson and live. Brontë's own sympathy lay more with Frances Henri in The Professor, who scorned voluntary death in the hope that she would "have the courage to live out every throe of anguish fate assigned me" (226). Later in the century, Victoria Crosse (Vivian Corey) took on Grant Allen's The Woman Who Did (1895) in her The Woman Who Didn't (1895). Allen had described a broken, fallen heroine who initiates suicide by taking prussic acid and then arranges herself on a bed with white roses at her breast. Crosse's heroine, Euridyce, lives on and employs willpower to endure a loveless marriage and defy premature death.

Victorian Images of Women, Female Willfulness, and Suicide

Despite the insights of such women writers, the image of woman as the strong-willed, "vengeful fury" better approaches the dominant Victorian view of female willfulness and suicide because it begins to make myth of willful womanhood (See Auerbach, ch. 1). A decade and a half after Kingsley wrote about Ida, a male writer for the Westminster Review (1865) sketched in the image of the fury. She was the new woman abroad, one who possessed "not only the velvet, but the claws of the tiger." She was "no longer the Angel, but the Devil in the House." With her in mind, this writer reframed an old proverb to read, " man proposes, woman disposes" (Wise, 568) This sentiment was virtually paraphrased by the painter Edward Burne-jones, who said of woman: "Once she gets the upper hand and flaunts, she's the devil — there's no other word for it, she's the devil . . . as soon as you've taken pity on her she's no longer to be pitied. You're the one to be pitied then (11). And so she-wolves grew in place of pet dogs. Monstrous women represented female energy bristling with will, whereas male monsters like Hyde depicted masculine energy dispossessed of will. Even when they disposed of themselves, such women were insidiously dangerous because they then threatened the very being of males who were their counterparts in willpower. Ever "vengeful," these monstrous women suggested that willpower was a way into, not out of, self-destruction. They began to displace displacement and needed to be mythologized endlessly in efforts to distance them. Fear of Mary Brough's sexuality and of her anger caused her rebirth in the press and in the popular mind as an utterly appalling miscreation. Fear of Bertha Rochester's female loss of control caused the fictional Rochester in Jane Eyre to lock her up like an animal, to dehumanize her into the ultimate monster she became until she set fire to her cage-like [129/130] home, destroying both herself and, for a time, the will of Rochester in the bargain. A broken man, the once potent Rochester could only be restored by the intuition and ministration of Jane.

Cesare Lombroso, Evolutionary Regression, and Suicidal Women

Making monsters of women was not only the pastime of the press or of novelists during the nineteenth century. Criminologists like Cesare Lombroso, an Italian who was widely admired in England, included women in their theories of evolutionary regression or atavism. For Lombroso, criminals became a manifestation of such atavism; they were less evolved beings, closer to other primates than were most people. And because women were already lesser beings than men, female criminals were the most atavistic of all. In The Female Offender (1893), Lombroso discussed woman's hysteria, hand and facial anomalies, lunacy, tattoos, and of course suicides. To his mind, female offenders were appallingly dangerous because in them piety and maternalism were missing. In their place were "strong passions and intensely erotic tendencies, much muscular strength and a superior intelligence for the conception and execution of evil." To Lombroso "it was clear that the innocuous semi-criminal present in the normal woman," had in these women been "transformed into a born criminal more terrible than any man." His "criminal woman is consequently a monster" (150-152). Lombroso also believed that women were less impelled to suicide than were men because they felt pain less. When thwarted in love, however, their monstrously passionate natures leapt to the fore, so that far more than men, women in love turned into self-destructives.

Lombroso reached an English soil well prepared for his coming. Nevertheless liberals like Mill and feminists like Cobbe had earlier raised voices of protest against such dehumanizing of women. In On the Subjection of Women (1869), Mill questioned the right of men "to worship their own will as such a grand thing that it is actually the law for another rational being" (77). Absolute domestic tyrants were for him "absolute monsters"; lesser tyrants, more the rule in Victorian England, were "savages," "little higher than brutes" (64-65). Mill thus found more primitiveness in men than in women. So did Cobbe, who also thought that to treat woman, who "has affections, a moral nature, a religious sentiment, an immortal soul...as a mere animal link in the chain of life" was itself "monstrous" (Cobbe, 9) These two earlier writers helped stand the myth of atavistic womanhood on its head. Later, Oscar Wilde would further invert and deflate it. In The Importance of Being Earnest (1895), Jack says of Lady Bracknell, "she is a monster, without being a myth, which is rather unfair. " (Wilde, 50).

Lovelorn Suicidal Women

But it was not necessary to treat women as fiends in order to distance them from men. Other myths about their nature would serve equally [130/131] well, especially when it came to suicide. When suicidal women were not feared as willful Medusas, they were usually disdained or pitied as the yearning lovelorn. They displayed that second-class will so often projected upon them. If men had been their main reason to exist, one important supposition went, losing them meant indifference to life. Of all the constructs about women and self-destruction, this one had the deepest hold on the Victorian imagination for the longest time. A catalogue listing all works of art on this subject would have to run on for pages. Domestic melodrama snatched dozens of jilted women from the jaws of suicide, while broadsheet after broadsheet sensationalized their plight. Ophelias and Crazy Janes, madwomen frenzied for want of their lovers (see Showalter, intro. and ch. 3), haunted the pages of Christmas books and annuals. In Forget-Me-Not: A Christmas and New Year's Present for 1827, the orphaned Ida is abandoned by her higher-born beloved, Osmond, in favor of a wealthier bride. Poor Ida gazes on Osmond's nuptial pride and turns her "lone footsteps to the shore." "A plunge was heard — a dying groan — / A bubble in the moonbeam shone; / A light form rose, then sunk again, / And Ida slept beneath the main" (Shoberl, 204-206) The strength of Ida's stereotype would be confirmed by Victorian coroner's juries like Margaret Moyes's, that would ask: "Was this dead woman crossed in love?"

Ida and her jilted sisters — both real and imagined — were often sympathetic figures, victims of men who were superior to them in status, power, or physical strength, and the source of sympathy for them very often Jay in male perceptions of female honor. Many believed with De Quincey that "there is no man who in his heart would not reverence a woman that chose to die rather than to be dishonoured" (VIII, 399). But deserted women who committed suicide did so not only out of bereavement, Many were seduced as well as abandoned. They killed themselves rather than face the shame of "falling," for fallen women immediately gained new willpower in Victorian eyes. Sinful creatures now considered responsible for their own destinies, they became blameable for their wrong choices (see Mitchell, p. x). If they lived on, as most did both in Victorian literature and in actuality, they might either become prostitutes or else atone for their sin through good works, through death-in-life, or through some untimely demise. Ruined Hetty Sorrel in George Eliot's popular Adam Bede (1859), for instance, became an infanticide. After killing her illegitimate offspring, she was punished for her fall by a sentence of hanging — later commuted to transportation but followed by an early death. More common than infanticide for the women who fell was a further fall into prostitution. In Household Words (1853) Dickens tells of "case number fifty-four" at the Home for Homeless Women who "had stayed out late one night, in company with a 'commissioner' [131/132] whom she had known abroad, was afraid or ashamed to go home, and so went wrong" (1911; p. 408). The Home itself was an attempt to counter such prostitution. Established in the late 1840s by a group of women, it set out to find work for young women who had "already lost their character and lapsed into guilt" or to lend an opportunity to "fly" from the "crime" of prostitution (395). In literature more than in life, losing character did mean losing life. William Acton's classic study of prostitution pointed out that prostitutes did not have a high rate of suicide (Acton, 38). In popular poetry like William Bell Scott's "Rosabell," however, when the woman "goes wrong," she before long develops the scornful laugh of the street-walker. People like Scott's narrator can then only moan: "Descent is easy: stage to stage / Facile, they say, and swift, alas" (I, 151). The usual end of such an archetypal fall was self-destruction. Scott's poem concludes with a fatal prophecy for such women: "And every lamp on every street / Shall light their wet feet down to death."

Fallen women were considered deadly to more than just themselves. Scott's Rosabell was led astray not only by her male lover but by the already hardened Joan. Unfallen Victorian women, like those who established the Home for Homeless Women, had to be careful to avoid the taint of the fallen. In discussing the importance of Ladies Committees to female penitentiaries, John Armstrong saw both pros and cons for their existence. Ladies could show requisite pity for their sisters, but it might not be "advisable for pure minded women to put themselves in the way of such a knowledge of evil as must be learned in dealing with the fallen members of their sex." (Armstrong, 375-376) Moreover, the taint from an actual fall could cling to middle-class or even upper-class women for the rest of their lives, another stigma widely illustrated in Victorian literature. In Arthur Wing Pinero's The Second Mrs. Tanqueray (1893), Paula, the cynical second wife of Aubrey Tanqueray, is much beloved by her husband but resented by his daughter, Ellean. By an odd quirk of fate, the daughter falls in love with a former lover of the second Mrs. Tanqueray. To save Ellean from that lover, Paula tells Aubrey of her own affair but then refuses to save herself. She had once revealed to Aubrey that she would have killed herself had they ever parted, but now commits suicide rather than live with his and Ellean's knowledge of her past. Similarly in Dickens's Bleak House (1852-53), after her illegitimate liaison is discovered, Lady Dedlock wanders on to self-induced death by exposure, a fitting metaphor for the revelation of her fall.

Paula Tanqueray and Honoria Dedlock die willingly but only after attempts to live down a deeply internalized sense of descent. Other women in Victorian literature choose death-in-life after a self-perceived fall. They live disheartened, suicidal lives that confirm what they feel [132/133] friends or society must think of them. Marian Erle in Aurora Leigh (1856) becomes a living dead person twice in Barrett Browning's poem. First she flees home to avoid falling victim to a neighboring squire, running until she drops, and then she feels "dead and safe" (Browning, p. 112) Years later she is more severely victimized. Drugged and raped, not "seduced" says she, but "simply murdered" (223), she becomes pregnant but indifferent to her own life. "I'm dead," she admits. "And if to save the child from death as well / The mother in me has survived the rest / Why that's God's miracle you must not tax, — / I'm not less dead for that" (224). Marian is only restored by the ministrations of another woman, Aurora Leigh. Less revivable is Dahlia Fleming in George Meredith's Rhoda Fleming (1865), one of the most profound Victorian studies of living death after sexual fall. Dahlia and Rhoda are the two flowerlike daughters of a dead, garden-loving mother. Beautiful, natural, and naive, Dahlia goes to the city, is seduced by Edward Blancove, the worldling son of a banker, and when he deserts her, she evades her family. She is about to marry a ruffian when she is discovered by Rhoda's suitor. Morally strong but blindly unaware of the dangers of supposedly correct behavior, Rhoda is willing to see Dahlia married off after her fall because it will make her respectable again. Only very slowly does Rhoda realize that acts like marrying off are what constitute immorality. Meanwhile, Dahlia dies to life as had Marian Earle. Unable really to accept anything but Edward, she maddens, unsuccessfully attempts suicide, and then succumbs to tedium vitae. Eventually Edward decides he will indeed have her, but by then she has deadened to him as well.

Central to Meredith's portrayal of Dahlia is others' misapprehension of her deathlike indifference. It begins while Edward is still present, on the night when be will leave her. Dahlia, again like Marian Erle, directly states that she is dead, but Edward counters her statement with baby talk. Meredith brilliantly reads both sides of the gulf between his characters. Edward thinks of Dahlia as a child, a will-less, lesser being, and so feeds her child's talk. But Dahlia is love-starved, not weak, and resents this gibberish "as not the food she for a moment requires" (Meredith, vol. 5, p. 98) It sickens her and in turn disgusts Edward, who is about to go out to his club for dinner. Intuiting Dahlia's feelings, Edward glances at the real plate of food that Dahlia is about to have and muses to himself that the "potatoes looked as if they had committed suicide in their own stream" (WGM, 100). First realizing, then denying, the growing compassion he suddenly feels for Dahlia, he rationalizes that no person of character could knowingly sit down to a meal like Dahlia's, and he abruptly leaves. Much like Edward, Rhoda too lives on the opposite side of the abyss from Dahlia, who after Edward's abandonment becomes like one [133/134] of the damned. This new Dahlia, who does "not wish to live but cannot die" (WGM, 381), puzzles Rhoda, who "had imagined agony, tears, despair, but not the spectral change, the burnt out look" (WGM, 38o). The sisterly gulf is finally bridged, but like Hetty Sorrel, Dahlia lives for only a few years and then only as a kind of nurse to Rhoda's children. Her heart in "ashes" except regarding her nieces and nephews, Dahlia dies uttering the words, "Help poor girls" (WGM, 499). These final words of the book, an 1886 revision of the 1865 text, leave Meredith's reader recalling Dahlia's will to die more than Rhoda's new fecundity and corrected moral vision. In 1865, the story had ended with Edward's wondering whether Dahlia's ultimate independence from him meant that she was a greater or lesser being than before — with his trying, as it were, to fit her into a new mythology. Dahlia's last words refocussed the novel as a plea to alleviate women's pain.

Found Drowned

Earlier in Rhoda Fleming, Meredith had Dahlia imagine "that perchance if she refrained from striving against the current, and if she suffered [134/135] her body to be borne along, God would be more merciful" (WGM, 382). What Dahlia envisioned here is another female-associated type of death, dissolution into a body of water. Suicide by drowning, a common route for those women who did take their own lives, was the way most visual artists and many writers of the Victorian era imagined female suicide. It was as though women drowned in their own tears, or returned to the water of the womb, or, as Freud believed, were delivered of a child (see Strachey, XVIII, 162 n) when they made their final retreat into water. Fallen women thus drowned in grief or in conjunction with childbearing, both of which were associated with their state and with female fluids in general. In Victorian literature, many fallen women openly acknowledged this affinity with water. Fronting the river, Martha Endell in David Copperfield exclaims, "I know it's like me! . . . I know I belong to it. I know that it's the natural company of such as I am!" (1981; p. 581) Martha's creator, Charles Dickens, certainly seems to agree. Nancy in his Oliver Twist also feels destined to drown. "How many times," she ponders, "do you read of such as I who spring into the tide. . . , It may be years hence, or it may be only months, but I shall come to that at last" (1966; p. 354) And in "Wapping Workhouse" from The Uncommercial Traveller, Dickens's narrator, looking down into dirty water from a swing bridge, hears of women "always a headerin' down here" (1911; p. 22), down to the water.

If Dickens presented a phalanx of fallen women moving toward the Thames, Thomas Hood preferred to focus on only one. In his enormously popular and influential "Bridge of Sighs" (1844), Hood, who had been moved by Mary Furley's suicide attempt and trial for infanticide, determined to write about "Waterloo and its suicides" (Hood, 392) Hood's poem opens by presenting

One more Unfortunate,

Weary of breath,

Rashly importunate,

Gone to her death.

Basically, the poem is an impassioned plea for charity toward this homeless, "lost" woman, and predictably, men like Horsley found it too soft. For Horsley "it tinged suicide with a halo of romance, and afforded a justification of cowardice and crime to the unreasoning and hysterical" (Horsley, 509) Nevertheless its strong sentiment deeply stirred most Victorian consciences. Hood's unfortunate is described with great tenderness. As she is brought up dead from the water, the poet sings her a merciful kind of dirge:

Touch her not scornfully;

Think of her mournfully,

Gently and humanly;

Not of the stains of her

All that remains of her

Now is pure womanly.

(SP, 15-20)

[135/136] Once she is plucked from the river, Hood sees her as washed clean of her sins, in effect baptized by the Thames. Yet kindly as Hood is toward his "unfortunate," one can hardly miss an underlying message that the only good prostitute is a dead prostitute:

Make no deep scrutiny

Into her mutiny

Rash and undutiful:

Past all dishonour

Death has left on her

Only the beautiful.

(SP, 2 1-26)

This poor woman has been willful, but has been punished and bathed into attractiveness by the river-left clean, limp, will-less, but dead.

Like

the famous Victorian painting of Ophelia (1851-52) by John Everett Millais,

Hood's poem on his unfortunate's death has a quietude and beauty that belies

its subject. And like many Victorians, both Hood and Millais had Shakespeare's

flower bedecked corpse in mind when they thought of the suicides of jilted,

fallen, or mad women. Recall Wilde's Lord Henry teasing Dorian Gray by suggesting

that his Hetty might be floating in a mill-pond with water-lilies all around

her. Such Ophelias became a phenomenon in Victorian England. Elaine Showalter

has uncovered the fact that asylum superintendents with cameras actually dressed

up inmates in Ophelia-like costumes in order to get "authentic" photos

of the phenomenon. Then art, trying to imitate life, which was really imitating

art, sent stage actresses to the asylums to study the crazy Ophelias there.

Showalter believes that "the figure of Ophelia eventually set the style

for female insanity" (92). Certainly Hood was fascinated by the image when

he selected "Drown'd! drown'd" from Hamlet as the epigraph

for "The Bridge of Sighs." Hood's epigraph in turn was chosen by Abraham

Solomon as the title for a painting that he exhibited at the Royal Academy in

1860. Solomon's representation, now extant only in a lithographic reproduction,

features yet another woman pulled out of the water from beneath Waterloo Bridge.

A waterman with grappling hook stands nearby, and a woman folds the dead girl

in her arms. Other lookers-on in this visual narrative remain more indifferent,

and Solomon seems to be relaying the same overt message as Hood: "Londoners,

learn to show more compassion!" Interestingly, a reviewer for The Athenaeum

(12 May 1860) directly compared Solomon with Hood and found Solomon lacking

because his drowned female was not beautiful like Hood's:

Like

the famous Victorian painting of Ophelia (1851-52) by John Everett Millais,

Hood's poem on his unfortunate's death has a quietude and beauty that belies

its subject. And like many Victorians, both Hood and Millais had Shakespeare's

flower bedecked corpse in mind when they thought of the suicides of jilted,

fallen, or mad women. Recall Wilde's Lord Henry teasing Dorian Gray by suggesting

that his Hetty might be floating in a mill-pond with water-lilies all around

her. Such Ophelias became a phenomenon in Victorian England. Elaine Showalter

has uncovered the fact that asylum superintendents with cameras actually dressed

up inmates in Ophelia-like costumes in order to get "authentic" photos

of the phenomenon. Then art, trying to imitate life, which was really imitating

art, sent stage actresses to the asylums to study the crazy Ophelias there.

Showalter believes that "the figure of Ophelia eventually set the style

for female insanity" (92). Certainly Hood was fascinated by the image when

he selected "Drown'd! drown'd" from Hamlet as the epigraph

for "The Bridge of Sighs." Hood's epigraph in turn was chosen by Abraham

Solomon as the title for a painting that he exhibited at the Royal Academy in

1860. Solomon's representation, now extant only in a lithographic reproduction,

features yet another woman pulled out of the water from beneath Waterloo Bridge.

A waterman with grappling hook stands nearby, and a woman folds the dead girl

in her arms. Other lookers-on in this visual narrative remain more indifferent,

and Solomon seems to be relaying the same overt message as Hood: "Londoners,

learn to show more compassion!" Interestingly, a reviewer for The Athenaeum

(12 May 1860) directly compared Solomon with Hood and found Solomon lacking

because his drowned female was not beautiful like Hood's:

What respect does not Hood pay to the beauty of the fallen! how singularly felicitous are the epithets throughout! how he dwells upon the natural incidents [137/138] of the suicide, forming a background, as it were, full of living nature, to his picture in words! We may be sure that had the brush been the exponent of Hood's wise-heartedness, he would never have neglected to show, with all possible fidelity, the awful stillness of the dawn looking down upon the climax of guilt, confident as he must have been that by painting Nature alone could he do her justice.

The contrast between loveliness in death and guilt in life, between willlessness and willingness, was what the Victorians wanted to see in art about suicidal women. It amounted to a kind of necrophilia.

George Frederic Watts, Found Drowned (ca. 1848-50). Reproduced by permission of the Trustees of the Watts Gallery, Compton. Click upon images for larger pictures, which take longer to download.

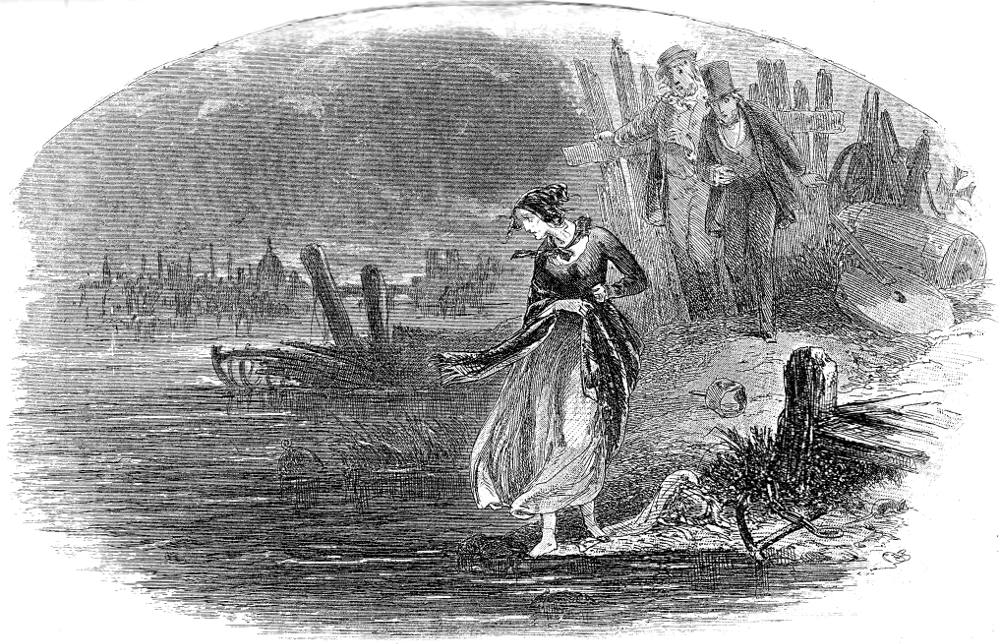

In the visual arts, the Thames and its bridges came to represent the end of the line for such desperate women. For two decades after the publication of Hood's poem, artists like Solomon rendered women as dead or about to die on the banks or bridges of London's central river. Gustav Doré's The Bridge of Sighs, with its darkened arc of abriage, forlorn fernale figure, and hulking church dome, epitomizes these works. From 1848 to 1850, George Frederic Watts worked on Found Drowned, a portrait of a woman washed up by the tides under Waterloo Bridge, her body laid out in the form of a cross. Then came Phiz's illustration for David Copperfield (1849-50) entitled "The River." It [138/139] shows Martha Endell staring out into her kindred river, one toe already in the water, with a ruined vessel jutting out behind her and St. Paul's dome in the background. And the third and last painting of Augustus Egg's series Past and Present (1858) would depict the adulterous wife wrapped in a shawl, with the thin, small legs of her illegitimate child protruding out from under it. She stares at the moon from underneath the Adelphi Arches near Waterloo Bridge. If the tide is out for the moment, it will not be for long; the woman's beloved moon will see to that. Meanwhile she awaits death by resting under a poster bearing the word "VICTIMS."

Left: Augustus Leopold Egg, Past and Present No. 3: Despair (1858). Tate Gallery, London.

Right: Paul de La Roche, The Christian Martyr (1855). Delaware Art Museum, Wilmington, Delaware. Click upon images for larger pictures, which take longer to download.

In each of these pictures, arches or arcs frame the women. Even Phiz's etching, which is free of bridges, has an arched sky at its upper edge. The same is true of Paul Delaroche's The Christian Martyr, an 1855 French painting of a drowned woman floating with a life-ring drifting beside her, placed on the canvas like a halo above her head. Above her, too, the heavens are opening. This popular painting passed into British hands in 1866 and was hailed as the French Ophelia. Ophelia, of course, was also framed with an arched upper edge, suggesting that arcs were a convention for rendering drowned, female suicides in the visual arts. [139/140]

Hablot K. Browne, The River, illustration for Charles Dickens's David Copperfield (1849-50).

They might have been chosen as reminiscent of religious altar paintings, by association purifying weaker vessels, much as did Hood's poem. Certainly Delaroche's work demands such an interpretation. Or they might have functioned as subtle reminders of eggs or of the womb, enclosing women in symbols of their beginnings, their power, or their fall. They also serve to distance the viewer from the suicides, replicating proscenium-arched stage sets and reinforcing the drama of suicide. Whatever their other functions, they certainly helped draw attention to women, water, and death. <.p>Airborne Women

A second image that saw a series of visual representations during the Victorian period was that of women plunging through the air from a height. The woodcuts of deaths from the Monument — with Margaret Moyes dropping like a lead weight or with her counterpart in the 1841 [140/141] [141/142] suicide flying with arms outstretched, skirts billowing, and collar uplifted like wings — became prototypes for a number of graphics, mostly associated with popular literature.

Left: The Leap from the Window, illustration for G. W. M. Reynolds's Mysteries of the Courts of London, Bew Series. 2 (1849-56): 25. Middle: George Cruikshank, The Drunkard's Children, "The Poor Girl Homeless, Friendless, Deserted, Destitute, and Gin-Mad Commits Self-Murder" (1848). Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Right: Cover illustration for Charles Selby's London by Night, Dick's Standard Plays, no. 721 (1886).

Reynolds's Mysteries of London (1844-46) was illustrated with a young woman fleeing from the embraces of a royal "personage" and leaping into space. Her arms fan out in a ballet-like gesture of entreaty, and her skirts fly like a parachute. In 1848, George Cruikshank etched a now famous flying woman for his series The Drunkard's Children and entitled it "The Poor Girl Homeless, Friendless, Deserted, Destitute, and Gin-Mad, Commits Self-Murder." His scene combines pathos with brilliance and bridge arcs with flying. Cruikshank's young woman's body bends upward at the middle, virtually reversing the arch of the bridge in its unwillingness to die. As she falls, the Drunkard's Daughter covers her eyes, and her hat trails her skirt and hair, which almost touch one another as she arches her back. Two onlookers, a horrified man and impassive woman, peer over the edge of the bridge.

Eliza's attempted suicide, illustration for Dion Boucicault's After Dark; A Tale of London Life (1868).

This powerful rendering yielded a host of imitations, particularly as illustrations for melodramas (see Meisel, 140). Act 1, Scene 6 of After Dark (1868) was provided with a woodcut reminiscent of Cruikshank, Egg, and Doré, all three. In it young Eliza drops from Blackfriars Bridge and flies like a witch across the moon, but with hands held up to the sides of her head in despair. The perspective from under the arching bridge is like Egg's in Past and Present, no. 3, but here a St. Paul's prominent on the horizon and a gibbet-like bridge-support looming up on the right both cry out in condemnation of the girl's rash action. Closer to Cruikshank was an 1886 cover illustration for Charles Selby's melodrama, London by Night (1844), a production that actually tried to incorporate a scene dramatizing Crulkshank's Drunkard's Daughter. The illustration repeats Cruikshank's scene but with only one onlooker and a nearly vertical woman. Here once again the arms are outstretched in flight, but this young person is trailed by a cape and looks rather like an angelic superwoman.

All these images of airborne women bear a message different from the Victorian Ophelias. These women are not deadened or will-less. Their soaring is — for a moment — an act of autonomy or self-assertion. Symbolically, flying signifies raising oneself, both in terms of status and in terms of morality. In her plunge, Reynolds's heroine is trying to escape compromise. The others, shown flying rather than failing, are choosing the course of their own descent. They are kindred to Lady Cecilia Harborough in Reynolds's Mysteries, who, thinking of the Monument, had theorized that "from the river I might be rescued; but no human power can snatch me from death during a fall from that dizzy height" (II, 69). If these figures confirm "fallen" woman's status, they also [142/143] convey determination. And probably because of their imminent deaths, Victorians made momentary heroines rather than monsters of these women. They were not associated with witches, those legendary fliers who are always considered willful and dangerous. Witch fights represent magical powers, and judges in 'witchcraft trials presupposed the reality of their flying (see Duerr, 1985). But in Victorian flights like Eliza's from Blackfriars, men look on in horror rather than anger, hailing rather than impaling the young Eliza. In the case of these doomed Victorian fliers, sentiment won out over fear.

Repeated representations of women and water and women and flight confirmed the statistical knowledge of female means of suicide. Ellis points out that women chose falls from heights twice as often as did men (334). Yet the profusion of images also helped perpetuate the inaccurate myth of frequency of female suicide (people found drowned were not in fact counted as suicides. See Jopling, 39), another myth that women writers strove to counter. In literature by women of all classes, female characters most often lived on past suicidal urges and pointless atonements. Charlotte Brontë certainly took Elizabeth Gaskell to task for killing off her heroine in Ruth (1853). After a long and heroic struggle to respectability and self-reliance, Ruth dies of a fever contracted while nursing her one-time seducer back to health. To Gaskell, Brontë vehemently protested what seemed a needless sacrifice. "Why Should she die? . . . And yet you must follow the impulse of your own inspiration. If that commands the slaying of the victim, no bystander has a right to put his hand to stay the sacrificial knife, but I hold you a stern priestess in these matters" (Shorter, II, 264) Brontë's own protagonists live on, sometimes against great odds like those faced by Lucy Snowe in Villette. So does Lady Blessington's Clara Mordaunt in The Governess (1839). After her father's suicide, Clara survives, but with "a dark cloud" over her past and a "shadow" over her future (Blessington, 60). And so do George Eliot's fearful, weak Hetty and gentle, Zionist Mirah. These well-known characters had powerful counterparts in lesser-known works of fiction about working women. Nelly, in Sarah Whitehead's two-volume novel, Nelly Armstrong (1853), works as a maid in Edinburgh, becomes pregnant, loses her job and then her baby, despairs, but refuses to kill herself because she hopes for a heavenly reunion with the child. Another Nelly, the sister of Lucy Dean in Eliza Meteyard's "Lucy Dean; the Noble Needlewoman" (1850) (Meteyard, 312-395) has an illegitimate child and is deeply distressed but goes off to Australia instead of off of a bridge.

Unmanly Male Sucides

When not busy saving their heroines, women writers also denied myths about female suicides by turning the tables and depicting male suicides — including male self-sacrifices and men made miserable by liaison or love. Charlotte Brontë refused to banish Jane Eyre to exhaustion [143/144] and death as a missionary in India, but Brontë's St. John Rivers meets such an end. So does Mary Augusta Ward's Robert Elsmere, who consumes his existence in self-sacrifice for others in the novel named after him (1888). Frances Trollope, in Jessie Phillips: A Tale of the Present Day (1843), destroys the male as well as the female in an illegitimate partnership. Young Jessie, a beautiful seamstress, is seduced and abandoned by wealthy Frederic Dalton. Dalton leaves her to a fate that includes childbirth, a workhouse, a coma, and a trial for an infanticide committed by Dalton. Worn out, Jessie eventually dies a natural death, [144/145/146] but Dalton commits suicide by throwing himself into a raging stream; Trollope uses water to punish her villain, not to bear off her heroine. With a different intent, Elizabeth Gaskell sends one of her male characters to the Thames to drown. This poor man, a sailor in "The Manchester Marriage" (1858), returns to England after a long absence. Presuming him dead, his wife has remarried. Unbeknownst to the wife, a nursemaid has allowed the long-lost man into the house to see his child, born while he was away. He prays next to the child's bed and afterwards flings himself into the Thames in a gesture of grief and self-sacrifice over the wife's new happiness. Although his wife never learns of all this, the second husband does and becomes a more thoughtful man as a result. Here Gaskell leaves the woman entirely free of the taint of suicide, which is used both as a symbol of male grief and as an admonishment urging male growth.

How unmanly such male suicides for love must have seemed to some Victorians becomes clear when one recalls Gilbert and Sullivan's Mikado (1885). There masculine suicidal lovelornness is spoofed in "Titwillow," sung by Ko-Ko, the Lord High Executioner of Titipu. Ko-Ko first hears the sound "titwillow" burst from a sad, suicidal "Dickybird" whose "willow, titwillow" echoes from his "suicide's grave" under a "billowy wave." Ko-Ko then croons his own "Titwillow" to the elderly Katisha:

Now I feel just as sure as I'm sure that my name

Isn't Willow, titwillow, titwillow,

That 'twas blighted affection that made him exclaim,

"Oh, willow, titwillow, titwillow!"

And if you remain callous and obdurate, I

Shall perish as he did, and you will know why,

Though I probably shall not exclaim as I die,

"Oh, Willow, titwillow, titwillow!"(Gilbert and Sullivan, 356)

If women writers showed less robust humor than Gilbert and Sullivan toward men dying for love, it may have been because they had in mind the fates of women trying to cope after male self-murders. Most men did not die lovelorn, but as we know, more men were pronounced felo-de-se than were women. The consequences were often both bitter loneliness and utter destitution for female survivors, even if confiscation did not occur. Early in the century, Harriet Cope's four-part poem, Suicide (1815) (Cope, 1815), looked into three instances of women suffering after suicides — Chatterton's bereft mother; a young wife who in her shame and grief over her husband's suicide begins to ignore her child; and a young unmarried woman whose father forbids her marriage, whose [146/147] lover then kills himself, and who considers suicide herself but has a vision of God warning her against self-murder. Imagined scenarios like Cope's dealt mainly with bereavement, but economic deprivation equally stunned the actual survivors of suicides. An 1825 family letter, written by a woman in London to a step-son in America from whom she had not heard for twenty-two years, tells a tale worthy of Brontë or Dickens. Ten years earlier, Ann Jewett's husband had become a debtor. He was taken off to Fleet Prison and from there on to Bedlam, where he ended his own life in despair. Left destitute, Ann had lived on minimal parochial aid and on the few shillings she could get by plying her [147/148] needle. At fifty-nine, however, she wrote to her step-son saying that she was still grateful to have learned sewing years before in convent school, but that her eyes were now failing her as was her subsistence. The letter is not a plea for financial help from a long-lost son nor a statement fraught with self-pity, but rather a moving assessment of the way things were, coupled with a contrasting look at the past. Ann ached for her old father who "brought her up with greatest tenderness," and wondered what he would feet if he should "rise from his grave" to see her at age fifty-nine. (For access to Ann Jewett's letter I am grateful to my friend Sarah Van Camp, a descendent of the Jewett family).

Ann Jewett's letter brings us back to the painful reality behind the statistics of suicide, much as the deaths or suicide attempts of real women can bring us back to the reality behind the myths. Beliefs about women and suicide were ingrained in women as well as men — so ingrained that some women opted to live them out. Mary Wollstonecraft had once, when deserted by a lover, filled her pockets with lead and tried to drown herself. Nina Auerbach sees George Eliot's Mill on the Floss as a mythic expression of Eliot's obsession with Wollstonecraft's attempt to live and die the myth of abandonment (Auerbach, 94). And for most of her married life Thackeray's wife Isabella lived hidden away, almost like a madwoman in the attic — much to Charlotte Brontë's embarrassment when she found out about Isabella only after dedicating Jane Eyre to her greatly admired Thackeray. Isabella made repeated attempts on her own life, all graphically described in Thackeray's letters to his mother. On an 1840 steamship voyage to Ireland, says Thackeray, "the poor thing flung herself into the water (from the water-closet) & was twenty minutes floating in the sea, before the ship's boat even saw her. O my God what a dream it is! I hardly believe it now I write. She was found floating on her back, paddling with her hands, and had never sunk at all" (I, 483) Having failed as the distracted, drowned Ophelia, the next night Isabella again tried to die. Thackeray says he then tied "a riband round her waist, & to my waist, and this always woke me if she moved" (I, 483). The novelist's descriptions move one to compassion for him, poor "Titmarsh," who asked himself "O Titmarsh Titmarsh why did you marry?" (I, 473) But they move one to even greater concern over the miserable Isabella, a confused Victorian woman, but hardly a heroine from Hamlet.

Wollstonecraft outlived the myth of suicide-by-drowning only to die later in childbirth; while poor Isabella Thackeray subsisted in various private asylums only to outlive Thackeray by thirty years. The novelist lamented in 1848 that the institutionalized "poor little wife of mine . . . does not care for anything but her dinner and her glass of porter (440). Isabella indeed became a timid, childlike ghost of a person, an enduring [148/149] but will-less Bertha Mason. On the other hand, Elizabeth Siddal, who suffered the ignominies of chill and cramp when posing in a bathtub for Millais's Ophelia and who came to represent the enduring image of Ophelia-madness after mid-century, succeeded in killing herself. Known to us almost exclusively through others' eyes, Siddal is a difficult person to grasp. A milliner discovered by the Pre-Raphaelite brothers and frequently used as a model by Rossetti, Siddal is the woman whose eyes Christina Rossetti saw looking out from so many a Rossetti canvas. On canvas, Siddal became part of the Rossetti myth, the saintly angelic woman or, after her marriage to Rossetti, the silent mysterious icon. In both cases, she was envisioned by her paramour as "other," a figment of his Victorian woman-worship, rather than a living partner. This artistic mythologizing seems to have entered the very lives of Siddal and Rossetti, but Siddal had difficulty living out a romanticized ideal with a man who was so often unfaithful, moody, and inattentive. Throughout their long engagement, Siddal gained Rosserti's attention through illness and talk of impending death. She wanted to appear mortal, not merely to be immortalized in paint. After the Rossettis' marriage, Siddal's illnesses continued, as did veiled suicide threats. In Brighton with her sister Lyddy, trying to recover her health, Siddal wrote to Rossetti that "I should like to have my water-colours sent down if possible, as I am quite destitute of all means of keeping myself alive. I have kept myself alive hitherto by going out to sea in the smallest boat I can find (qtd. in Doughty, 269).

All this suicidal misery was compounded when Siddal gave birth to a stillborn daughter. For months afterwards she would sit by the fire, rocking and staring at the empty cradle. Georgina Burne-Jones believed that Siddal "looked like Gabriel's Opbelia when she cried with a kind of soft wildness" (in Rosetti, I, 177) by the childless cradle. So often represented as Ophelia, Siddal seems finally to have become obsessed with Ophelia's lot, to have decided to live — and die — a fiction. Like her husband, she both painted and wrote poetry, the latter haunted by images of watery death. In her "A Year and a Day," the poem's persona reviews a dreamlike life and imagines a scene that all but recreates Millais's painting in words:

Dim phantoms of an unknown ill

Float through my tiring brain:

The unformed visions of my life

Pass by in ghostly train;

Some pause to touch me on the cheek,

Some scatter tears like rain.

[149/150]

The river ever running down

Between its grassy bed,

The voices of a thousand birds

That clang above my head,

Shall bring to me a sadder dream

When this sad dream is dead.

[see Donaldson, 126-133]

All dreams ended for Siddal on 10 February 1862, when, retreating to her room after a dinner out with Swinburne and Rossetti, she emptied a laudanum phial. After a few hours of labored breathing, Elizabeth Siddal Rossetti relinquished dead dreams and entered the ranks of the dead.

Last modified 12 May 2023