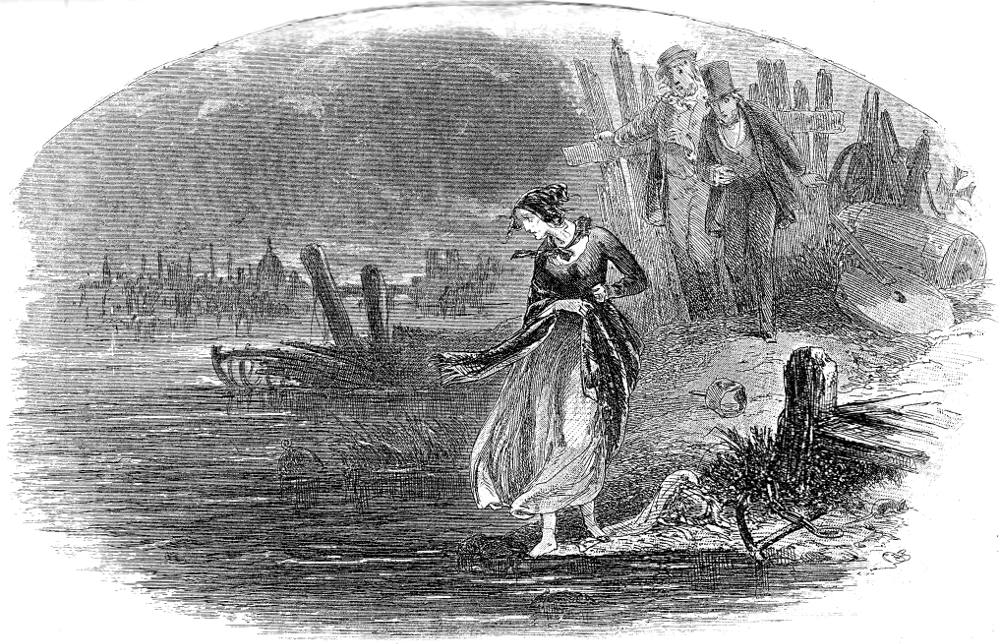

The River by Phiz (Hablot K. Browne). August 1850. Steel etching. Illustration for Chapter XLVII, "Martha," in Charles Dickens's David Copperfield. Source: Centenary Edition (1911), volume two.

Commentary: The Attempted Suicide of the Scarlet Woman

The sixteenth monthly number, which was issued in August 1850, comprises four chapters (chapters 47 through 50) rather than the usual three, although it was the customary thirty-two pages. For the first illustration, Phiz has chosen to realize the emotionally charged moment at which the despondent Martha, formerly a seamstress at Yarmouth, is about to drown herself at Millbank Pond on the Thames, the area's industrial wasteland forming a psychic backdrop for her attempted suicide which reprises Meggy Veck's attempted suicide in Trotty's dream vision at its culmination in The Chimes (1844), which likewise describes the plight of the Fallen Woman. According to J. A. Hammerton (1910), the illustration depicts the following passage:

. . . the girl [Martha] whom we [Mr. Peggotty and David] had followed, strayed down to the river's brink, and stood in the midst of this night-picture, lonely and still, looking at the water. [vol. 2, 293-94].

To intensify the girl's loneliness in a city of a million souls, Phiz has placed that well-known London landmark, St. Paul's Cathedral, on the skyline behind the twin pylons and the rotting hulk that serves as a visual metaphor for her life. However, as Kitton notes, "the scene should have been reversed, and from this point of view (the river-side at Millbank) the dome of St. Paul's is not visible, although it is shown in the picture" (104).

Phiz's working drawing for The River [Click on thumbnail for larger image.]

In etching the dark plate, Phiz may have failed to take into account that everything would be reversed in the printed illustration, so that the aerial perspective is in error. Indeed, the working drawing shows the scene reversed, with David and Mr. Peggotty entering the scene from the left rather than the right. However, in its symbolic and psychological value, the city on the horizon is a fitting detail, and, moreover, one which connects the previous scene, in which Steerforth's manservant, Lattimer, recounts for David the escape of Em'ly as dusk closes in upon the city in the distance.

Much more striking [than "The Wanderer"] is "The River" (ch. 46), the second dark plate Browne did for Dickens and the only one in David Copperfield (all forty of the etchings for Lever's Roland Cashel, overlapping in time of appearance with Copperfield, were produced by this method). Its uniqueness in this context is among several factors contributing to its success. It gives us the scene of a last-minute prevention of the standard watery fate of prostitutes, a fate which, the accompanying plate makes clear, could also have been Emily's. Phiz's conception of Martha at the river, and the technical differences between the two versions, seem to me more interesting than Dickens' hysterical narrative at this point. Phiz translates a strong and bold drawing in pen and wash into two carefully executed etchings which vary considerably in the handling of light and dark. Dickens rarely provided opportunities for sweeping, panoramic outdoor scenes, and when liberated from the confinement of interiors, narrow streets, or mild country views, Phiz seems to have indulged his propensity for dramatic landscape. (Ainsworth and Lever were to give him freer rein in this regard.)

As is often the case with dark plates, one steel is generally much darker than the other, and the lighter one (31A) depends more on subtle tonal variations in the mechanical tint, achieved by stopping-out, while the darker has a great deal more shading added by the etching needle, apparently over the tint. The effects are quite different, with the first steel subtler and smoother, and the second more strikingly dramatic in its contrasts and strong lines. In both versions the figure of Martha is given an unusual degree of solidity through the use of light and dark and, in 31B only, the modeling of her features. Surrounding objects, bits of junk and flotsam, are subordinated to her predominantly bright figure, as are David and Mr. Peggotty. The hazy presence of St. Paul's in the background may suggest — as it does more emphatically in one of the dark plates to Bleak House — the distance of official religious institutions from such outcasts. Otherwise, Phiz has followed the text and made good use of the smoking factory chimneys specified by Dickens. [Steig 128-129]

Commentary: The Nemesis of The Fallen Woman

The anti-Romantic, grimly social-realist vision of the Thames, with the Gustav Dore-like detritus of commercial shipping much in evidence, seems a fitting setting for the contemplation of suicide. Utilizing the potential of the bankside scene for pathetic fallacy, Phiz has carefully chosen background details to support the melancholy atmosphere established by the darkening sky and smoking chimneys in the distance: a stray buoy (centre), rotting pylons, a rat and anchor with chain attached (lower right, recalling the chain of marriage earlier in Mrs. Gummidge casts a damp on our departure) and a rusting boiler taken straight out of Dickens's description of the nightmarish scene have a cumulative effect. Martha is in sharp relief, a gaunt figure of black and white against a grey background from which emerge David — identified by his respectable top hat, waistcoat, and coat — and Mr. Peggotty behind. Both men are startled as it dawns upon them that Martha has chosen "this gloomy end to her determined walk" (294), rather than sought out some gloomy habitation. What Phiz does not show us, the metal-working fires, the barges and boats, and the shadow of the iron (i. e., Vauxhall) bridge, is as significant as what he has chosen to focus upon: a desperate, almost skeletal woman with "her shawl ... off her shoulders," staring down into the filthy water at her feet, about to make an end of herself as many a prostitute did in popular song and the popular press. In a moment, David, having tracked her to this dreary spot through Westminster, will recall her to herself, crying, "Martha!" and call her back from the brink of suicide in this lonely industrial wasteland anticipating T. S. Eliot's London scenes some seventy years later, a moral and emotional waste ground created by a bankrupt industrial system. But for the moment David cannot speak, for she is not yet within his grasp, and she remains an "unsettled and bewildered" (294) somnambulist whose wild manner is confirmed by her passionately crying out, "Oh, the river! Oh, the river" repeatedly as she recognizes her kinship with that "polluted stream" (293).

Related Resources

- The Remains of the Day: Death and Dying in Victorian Illustration

- O. C. Darley's Frontispiece in the New York edition (Vol. 1, 1863)

- O. C. Darley's Frontispiece in the New York edition (Vol. 2, 1863)

- O. C. Darley's Frontispiece in the New York edition (Vol. 3, 1863)

- Sol Eytinge, Junior's 16 Diamond Edition Illustrations (1867)

- Fred Barnard's 62 Illustrations for the British Household Edition (1872)

- Harry Furniss's Frontispiece David Copperfield for the Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910)

- Kyd's six Player's Cigarette Card watercolours (1910)

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. The Personal History of David Copperfield, illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz"). The Centenary Edition. London & New York: Chapman & Hall, Charles Scribner's Sons, 1911.

Hammerton, J. A., ed. The Dickens Picture-Book: A Record of the the Dickens Illustrations. London: Educational Book, 1910.

Kitton, Frederic G. Dickens and His Illustrators. 1899. Rpt. Honolulu, Hawaii: U P of the Pacific, 2004.

Steig, Michael. Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington & London: Indiana U. P., 1978.

Created 2 February 2010