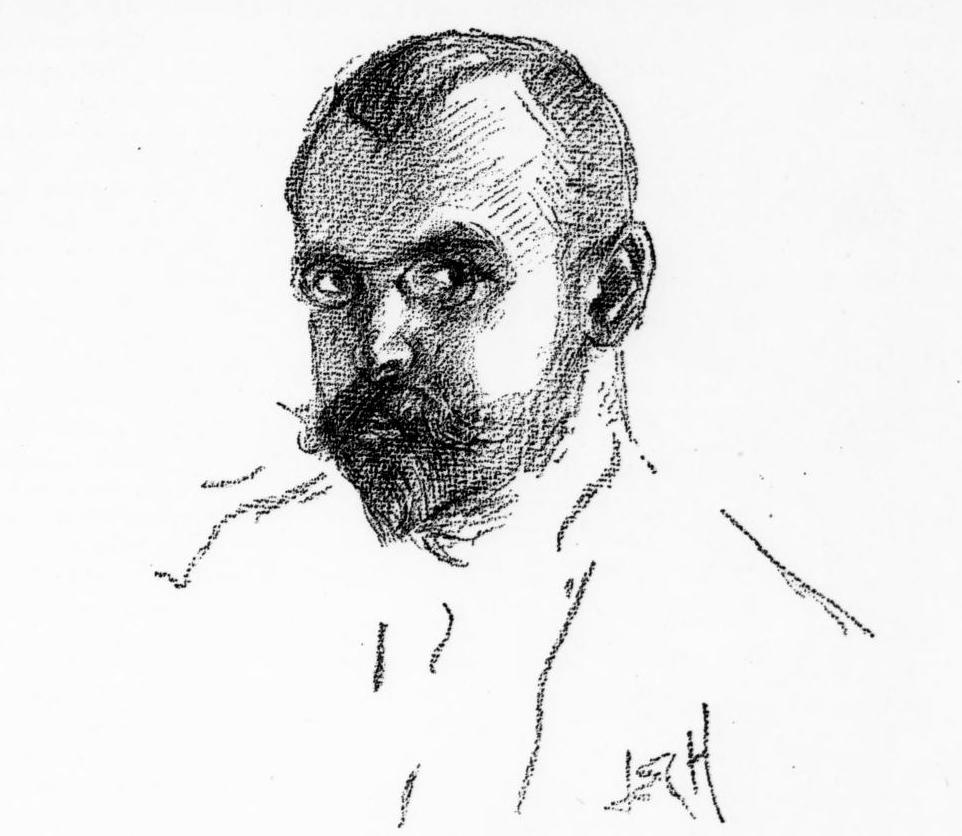

L. Raven Hill (Drawn by Himself.)

ERE I asked to select the draughtsman whose work best indicates the present trend in the rapid evolution of humorous art in England, I should probably point to Mr. L. Raven Hill as a typical instance of its major merits and its minor faults. As we have seen in the former papers in this series on our Graphic Humourists, humour first and drawing second were what our ancestors demanded, or, at least, all that they obtained. Good draughtsmanship it never occurred to them to require, and artistic excellence in its fuller sense was beyond their fondest dreams. Of the truth of this statement, the popularity of many of our early jesters with the pencil, with no serious claim whatever to be regarded as artists, affords ample and irrefutable evidence. Sir John Gilbert was the first to enter the arena with the reputation of being a serious artist highly accomplished and fully equipped. Before him we had artists worthy of the name, but they reached their excellence after they entered into the arena of humour, acquiring their skill by practice in the papers they had joined, with frank indifference to the aesthetic quality of their work. Then came Charles Keene and the rest, who brought the life-school to uplift what had hitherto been for the most part mere rough comic sketching, and imported into it some of the higher problems that exercised the artistic mind. One wonders what Kenny Meadows, Henning, and Alfred Crowquill would have thought — even Cruikshank and Gillray before them — could they have known that in the latter part of the nineteenth century their speciality in art would have been marked not only by an effort to present the fun of a subject with all its point, but worthily to treat the sketch as a "precious" work, hardly second to that of painting, with its problems of composition and silhouette, of light and shade, tones and values, and technique worked out to a solution with all the earnestness and endeavour that might be lavished on a diploma picture. Nowadays, the artist who [494/94] aspires to make a name with the greatest, studies from the life, works at the night-schools, enters a Parisian atelier, and then settles down—not to rival the frescoes of Michelangelo, or make a bid for the Presidency of the Academy, but to draw for the comic press, with Punch as the goal of his ambitions.

"Now why doan't 'ee 'ave two, pair: they be just the thing for any body a bit delicate like. Nothing I do like better than three or fower o' they for a little snack now and then."

Mr. L. Raven Hill, as I have suggested, is one of these. He was born in Bath, but received his artistic training at the Bristol Art School. About the year 1882 he entered as a pupil at the Lambeth Art School — that cradle of so many of our most successful artists — and there had the good fortune to work side by side with Mr. Charles Ricketts and Mr. Shannon; and the three became inseparables thenceforward, not only working together, but developing their art and living in company. At that time Mr. Ricketts was among the students the chief artistic influence, and that influence, as exercised upon Mr. Raven Hill, was salutary, and it was unquestionable. In 1885 Mr. Raven Hill proceeded to Paris, and there studied under various masters, deriving most of the benefit, perhaps, from M. Aimé Morot — he was a painter, then, and had some reputation as a chercheur — and after two years' absence in France, returned to England as a contributor to the exhibitions of pictures conceived and painted in the modern manner. But, in spite of a certain success, he found that the chief opening was for black-and-white work, and that the best way to "realise" it was to illustrate comic ideas rather than serious ones; and thus he drifted into a world of gaiety and humour for which he had not been specially educated, and for which he certainly had not suspected himself of any particular fitness. He had, it is true, drawn for Judy before he went to Paris, without any notion of finding his destiny in any such direction as that ; but on his return he worked extensively for Pick-Me-Up, Black and White, and The Butterfly, and in all of them he displayed capacity of a high order. The last-named magazine he started in 1893, in company with a small band of artists and writers who shared his ingenuous surprise that no paper in existence would give an artist an absolutely free hand — letting him do what he liked, and contenting itself with paying him a good price for his best work. In due course The Butterfly failed, though, in truth, it deserved a very different fate; and then the artist transferred his allegiance to the Pall Mall Budget, until it also died. In the pages of that journal appeared much of Mr. Raven Hill's best work. Then followed The Unicorn, which, born to an ineffectual struggle of only three weeks, succumbed to its birth-throes through misunderstanding and financial mismanagement.

It was thus as an artist carefully bred and educated, but attended in his publications by singular ill-luck, that Mr. Raven Hill entered the ranks of the humourists. Nevertheless, he was not faultless; for, although an acknowledged disciple of Charles Keene, he was one, as I have said, of the admirable trio of which Mr. Ricketts and Mr. Shannon were the other members. As a matter of fact, he shared their fault of occasional incorrectness of drawing; for they all belong to that school, or class, of artists of whom Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Ford Madox Brown were the greatest exemplars — who, however highly gifted with artistic instinct and inspiration could never (whether through lack of severe education or through inherent indisposition) assure themselves of impeccable draughtsmanship. Although the early drawings of Charles Keene were tight to a singular extent, he rarely was out of drawing. This tightness never was a fault of Mr. Raven Hill's; but inaccuracy of drawing, often. Nor is this shortcoming unknown to the artist — a shortcoming which, I imagine, arises somewhat from his practical belief in the principle of the Japanese artist, that impression — otherwise, memory — is of greater value in giving vitality to a drawing than any amount of deliberate searching after accuracy of proportion and truth of outline. At least, it may be said that it is the means of introducing the utmost unforced character into the drawing, while suggesting a sense of movement and actuality. "Nothing annoys me so much," Mr. Raven Hill once assured me, "as to see a thing obviously drawn from the model; mere correctness, for the sake of being correct, never did appeal to me. One might as well judge literature from the standpoint of an encyclopedia. This does not mean to say that I despise drawing; but I hate a thing to strike you as 'well drawn' in the manner of the average Salon picture." I have no wish to convey the impression that Mr. Raven Hill is a bad draughtsman; on the contrary, he is a draughtsman of amazing ability and skill; but he is not always right at the first attempt. You may convince yourself of this, by examining the original of that admirable drawing in which an old sea-salt is recommending, as an extremely light diet for the breakfast of a convalescent, "fower o' they," pointing to the fine flounders upon his barrow. In this the artist's radical correction in the drawing of the sternboard of the barrow will sufficiently illustrate the point under discussion. Although Mr. Raven Hill does not use the artist's-model for his drawings, he must not therefore be thought to revert to the ancient practice of complacently sacrificing art to humour. The opposite is the case. It is simply because he fears to sacrifice spontaneity that he will not allow the studio model to interpose between his sketch-book notes — between the scraps of paper which he carries in his waistcoat pocket for rapid use — and the finished drawing. The labour of correcting and re-correcting the drawing until it comes right may be great, but he prefers to take that course rather than to be hampered by the sight of the posed model. For all that, he keeps his eyes steadily upon the "men of 1860" — Millais, Keene, Fred Walker, Whistler, Pinwell, and others of the band — for the sake of their perfect qualities as illustrators, pure and simple; for in their work are to be found conjoined the highest decorative characteristics with technical excellence. It must be admitted, in defence of Mr. Raven Hill's view, that the decorative faculty in modern illustrative work has sadly fallen out of late, and that most black-and-white work starts, not as decoration, nor even from point of view of quality, but from a desire to make a scene as correct and coldly true as a photograph. There are, indeed, ample signs of a happy reawakening; [494-45] and in the movement Mr. Raven Hill has the credit of a considerable share.

THE GREEN-EYED MONSTER. "'Arriet, ain't it

about time you buried that sealskin?"

The leading objection taken by hostile critics to Mr. Raven Hill's work has usually been his too-close imitation of the work of Keene. It is true that he has aimed at the same economy of means, handled many of the same types and expressions, employed similar methods of suggesting light and form, cultivated the same style of "lining" as Keene's when the master used the pen and not the pencil. But surely the defence is easy against a charge the central point of which is the success of the imitation; for, after all, as Beaumarchais said, "On est toujours le fils de quelqu'un." Keene as a humourist and a black-and- white man summed up all the young artist's ideal; and not from an unworthy desire to "imitate," but out of genuine sympathy and healthy admiration, did Mr. Raven Hill study and learn what I may, without being misunderstood, call the tricks of Keene's method. As with Charles Keene, so with Mr. Raven Hill the main feeling is for expression, pose, light, and movement; form appears to me to appeal to him somewhat less.[495/96] This sense of the real function of the pen, too, naturally approximates Charles Keene's, and is certainly a leading characteristic. Mr. Sambourne and Mr. Phil May seem to care more for the sweep of their line than for the quality of the line itself; Mr Dudley Hardy thinks less still of line but wholly of expression; but Mr. Raven Hill spreads his sympathy over quality of line and humour both. Indeed, I need but refer the reader to the artist's etching, "On the Steps, Whitstable," if proof were needed of the resemblance, the genuine similarity, of Mr. Raven Hill's talent to Charles Keene's genius.

Miss Raven Hill.

Another point of resemblance, too, between the older artist and the younger is the comparative lack of sense of beauty in the case of their women. In power of genuine facial beauty, Mr. Raven Hill is vastly Keene's superior; but although he can give us what must be accepted as a "pretty woman," there is usually an absence of that grace and elegance which even in our avowed masters in the portrayal of low and common life, from Morland and Rowlandson to Mr. Phil May, were not wanting. Mr. Raven Hill is fond of rendering the ballet-girls; but in his passion for realism he draws their limbs with even more points of muscular development than Degas thinks it necessary to import into his models. And that, of course, means ugliness. In matters such as these, our artist and Mr. Du Maurier are as the poles asunder; for the former sacrifices to individuality what the latter devotes to a post-Raphaelite sense of beauty. A last point of resemblance to Keene should be mentioned. His love of backgrounds is as great as was that of the master, of landscape backgrounds greatest of all; and, like Keene, he loves to make them the setting of pictures which, be it observed, are usually a perfect and well-balanced composition of art, humour, and text, in equal and indivisible parts.

As a humourist — though, as I have said, a humourist only by chance and necessity — Mr. Raven Hill has established his reputation with the public. A comic situation recommends itself to him with instant effect, and its artistic possibilities spring to his eyes as quickly as they are realised by Mr. May's. Where he excels is in the investing of his figures with unconscious humour, as opposed to the "two figures and an underline" style of joke common to most of the comic papers. His joke, therefore, is part of the picture, and the picture, in the art jargon of to-day, is "inevitable." For the rest, his costers and his sea-salts are as coarsely and as richly vulgar as Mr. May's; his German professors as admirably true and life-like as Mr. Du Maurier's; his low and lower middle-life as vivid as Keene's; while his East-End Jews are distinct creations of his own wonderful powers of observation. How well would such a man illustrate the Ghetto writings of Mr. Zangwill!

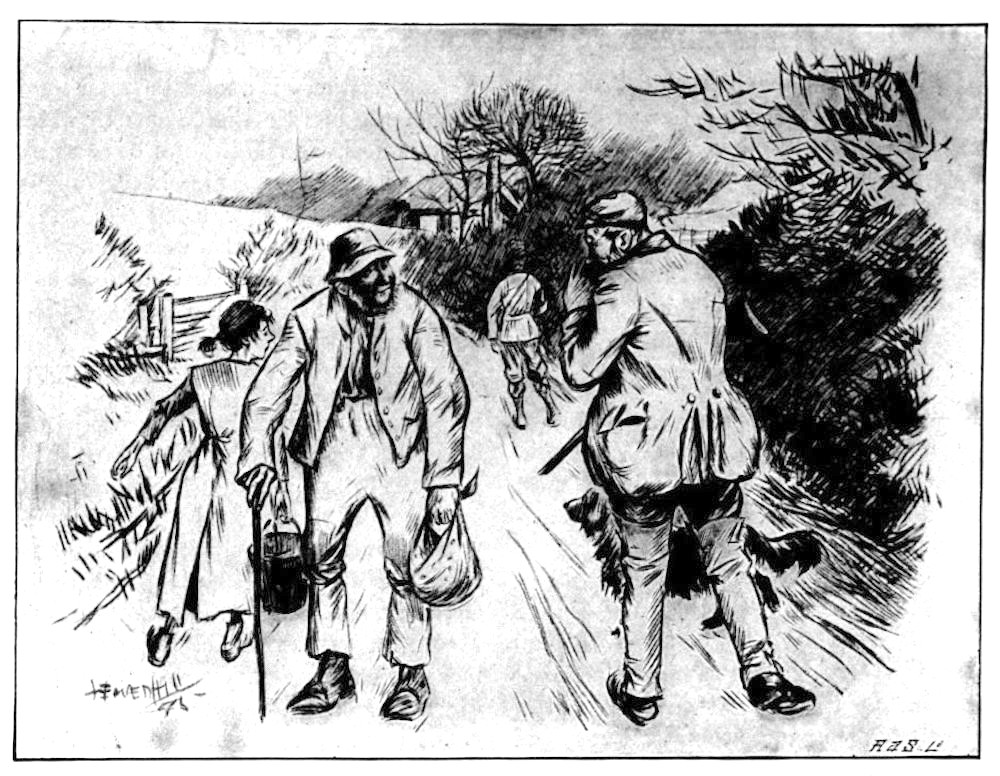

VILLAGER: "So you ain't had no luck this morning?" KEEPER: "No luck! 'E missed me twice!"

As an illustrator, indeed, Mr. Raven Hill's opportunities have been too few; yet his powers, as displayed in "The River Syndicate" drawings in Scribner's Magazine executed with the brush, are of striking ability, and full of animation and forceful beauty. It should be remembered that none but a humourist can be a successful illustrator, even of serious subjects; and if I desired to select the finest drawings of Mr. Raven Hill, the "comic artist," I should certainly include the pre-historic and Roman scenes in The Butterfly for the sake of their touch of true tragedy, as well as of artistic beauty of a higher kind. The illustrators, even of Dante, who have ever got public applause (whatever the [496/7] actual value of it may be), from Piero di Cosimo to Gustave Doré, have all of them been humourists of a pronounced type. If it were otherwise great conceptions could not be kept in check, as we have seen in the case of Blake. Humour and appropriateness are thus the chief notes in Mr. Raven Hill's art. At once shrewd and sincere in his artistic views, he knows how to make even blatant vulgarity supportable, and to infuse truth and life into his slightest sketches and studies. The secret of his successes, as of his failures, may be that he always draws a subject when he "feels like doing it;" and his artistic courage thus occasionally outruns his discretion. But in all things he is thorough and earnest; and if he leaves a drawing loose in handling, it is not from the carelessness with which he is often reproached, but from his principle, from which he does not depart, that a slight subject must be represented by slight treatment, and that solid work, elaboration of detail, and careful working out of light and shade, must be reserved only for such subjects as seem to him by their importance to call for it.

"No, no," he cried, when I once challenged him to enlarge upon his art; "my talking of my own art would remind me too much of that drawing of Phil May's in which a particularly plain old gentleman complacently exclaims — "How beautiful is everything in Nature!"

Bibliography

Spielmann, M. H. "Our Graphic Humourists: L. Raven Hill." The Magazine of Art. Vol. 19 (1896): 493-97. Internet Archive. Digitizing sponsor: Kahle-Austin Foundation. Web. 20 December 2021.

Created 20 December 2021