“We drank of it together, and walked together that evening on the hills above, where the fireflies among the scented thickets shone fitfully in the still undarkened air. How they shone!” — John Ruskin

“If only the Geologists would let me alone, I could do very well, but those dreadful Hammers! I hear the clink of them at the end of every cadence of the Bible verses.” — John ruskin

he intense struggle for control between scientific and religious thought from the mid-nineteenth century to 1900 caused a major shift in the English way of being. As soon as cherished terms and routines were put up for debate the evolution was unstoppable, moving with the speed and energy of the industrial revolution itself and producing continuous changes, almost by the week, in science, philosophy, the plots of fiction, the topics of poetry, and visual art. By 1900, a significant portion of religious energy in England had transformed into new forms of thought and art. It is not important whether this was forward or backward motion. It is enough to note that, as David Delaura points out in Hebrew and Hellene in Victorian England, a potent “Time Spirit” was at work. Thought at that time was like a stretchable fabric that was being pulled into new shapes, then re-controlled and set in place only to be stretched again. We discover the most distinctive vein of the new thinking in the lives of people with the interest, ability, and time to appreciate and respond to complex emotional or aesthetic influences. These intellectuals and artists could readily be offended or shocked so we feel for them as they endure one conflict after another fueled by everyone’s passionate awareness that something new was coming.

How Should We Be?

f one looks at intellectual turmoil in the Victorian era and the changes that led to modern thinking, one quickly comes upon Arnold’s pulling apart of religion and culture after mid-century. Arnold had grown up with religion as an organized human activity with duties, ceremonies, and requirements that supported belief in a non-human dimension of life that informed life fundamentally. But he promoted as more modern and useful an ideal he termed Culture, his mixture of religion and education. He knew this idea would dilute the English Church. He was victorious and it did. His Culture is now the foundation of the mission statements of most schools and universities: a humanistic ideal that “enlists the whole nature of man… [in a study] of a harmonious perfection, developing all sides of our humanity; and as a general perfection, developing all parts of our society” while placing religion in the background (Culture and Anarchy (complete text). The irony is that most intellectuals like Arnold had been brought up in the Church and so used religion as raw material to develop their secular belief system. In fact, John Henry Newman, an influential Anglican cleric who was Arnold’s Oxford role-model, may have inadvertently given Arnold the term culture.

Newman, whom DeLaura calls “ the embodiment of religious conservatism” (and who came to represent the old guard to Arnold, had a different solution to the future of England question; he and his Oxford Movement would purify the Church to strengthen it for leadership through troubled times. It happened that as Newman formulated his plan, he looked for an English word to cover the "cultivation" and "perfection" of the intellect in his ideal society guided by religion. Arnold decided the job could be done by Culture, pure knowledge, tinged with “spirit” but separate from the Church. This was a crossroads in the development of English thought. Newman did not plan to pass the baton of thought to Arnold, Arnold took it and parted with his teacher who remained dedicated to the supernatural order. During this change, both turned from Anglicanism, but instead of becoming more secular, Newman returned to Rome, its source, and eventually became a cardinal, while Arnold, an agnostic, declared the notion of a personal God unintelligible. Of course, there were consequences for both men. Newman found a new spiritual home but was ostracized by Anglican colleagues, friends and family while Arnold lived always with what E. D. H. Johnson describes as a “vaguely realized malaise.”

Little wonder that every Sunday, clergymen like Reverend Samuel Wilberforce counselled believers to “fly to known truths” and withstand doubt. Thomas Hardy expressed this strain on believers in “The Oxen,” which he published in the Times on Christmas Eve, 1915. During the upheaval of World War I, Hardy reached back to a legend from his childhood about farm animals everywhere kneeling to commemorate Christmas. Philip Allingham frames the feeling as “poignant loss at the passing of a secure world buttressed by… faith in presiding deity and community.”

If someone said on Christmas Eve,

“Come; see the oxen kneel,

In the lonely barton by yonder coomb

Our childhood used to know,”

I should go with him in the gloom,

Hoping it might be so. [“The Oxen”]

On Which Side are the Angels?

f you seek a line in the sand that divided the sides, you find it drawn inadvertently in 1850 by the reluctant revolutionary Charles Darwin whose famous work brought to national attention ideas that culminated casting doubt on Biblical narrative that geologists, linguists, textual critics, and even an Anglican Bishop had begun. In The Origin of Species, his aim is honest and his writing style patient and inviting, not combative. He wants only to convince readers to look at the slow natural changes of plants and animals (including human beings) over time, changes he describes with precision, and to consider that nature involves selection and thus evolution. But in those Victorian minds filled with belief in Genesis his idea exploded. The resulting national mental crisis was framed as a political issue by the statesman Benjamin Disraeli who announced his decision to reject the theory of natural selection and stay “on the side of the angels.” Josef Altholz summarizes the protest in “The Warfare of Conscience with Theology”: the doubt that underpinned science “was not only sinful… it rendered the doubter miserable, the absence of faith producing emptiness and unhappiness.” And so it did in cases like Arnold’s, but this was not necessarily a reason to deny science.

The poet Alfred Lord Tennyson countered, "There lives more faith in honest doubt,/ Believe me, than in half the creeds." Tennyson and liberal thinkers were believers of a different sort. To these descendants of the Enlightenment, Darwin’s discoveries reinforced their own self-discovery. The scientific viewpoint, unflinching, honest, and logical, had to be embraced. What’s more, for liberals it was tantamount to a sin to not use scientific thinking to solve social injustices. Liberals had work to do and the philosopher Henry Sidgwick spoke for many when he declared "A large portion of the laity now…. will not be satisfied by an ex cathedra shelving of the question, nor terrified by a deduction of awful consequences from the new speculations. For philosophy and history alike have taught them to seek not what is 'safe', but what is true.” John Stuart Mill put it this way: "I will call no [higher] being good, who is not what I mean when I apply that epithet to my fellow creatures, and if such a being can sentence me to hell for not so calling him, to hell I will go" (Altholz).

A Battle Over the Look of Things

t is as if we are watching a family fight. Everyone feels loyal to England but each faction examines the state of affairs and decides what’s best to keep and what should be thrown away. It is like redecorating on a grand scale. This is where the arts come in. This evolution/revolution was more than a matter of competing philosophies; it wove its way through the nerves of artists and stimulated the production of new work and new forms. Looking for examples, it is interesting to discover a change in Victorian visual thinking that was not in a studio or gallery but in church. The established church had been riven by conflicts for years and these battles had an aesthetic side. Bold adjustments to the look of things inside specific churches created an aesthetic controversy that was the outward sign of an inward struggle. Specifically, to combat waves of Dissent, partisans of Newman’s Oxford Movement thought visually and tactilely and advocated for a return to primitive liturgies which included ancient service-books and chancels, decorated vestments and ornaments from before the Reformation; they called themselves Ritualists and theirs was an aesthetics in the name of stabilizing what was worth keeping . In 1850, members of this reform movement opened the Church of Barnabas, Pimlico. Of course they met opposition and, in fact, were brought before the Privy Council to in effect explain the changes they were making to the Queen! The council examined the church’s furniture, ornaments, dresses, utensils and prayer-books, and the Ritualists were affirmed.

Left: Gilded wood carving from St. Barnabas, Pimlico. Right: Angels holding a scroll on the Organ in the Chapel of the Holy Sepulcher. Designed by by John Ninian Comper. After 1893. Location: G. E. Street's St. Mary Magdalene in Paddington, London. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Behind this case was apprehension about national identity. Was the Church Protestant or Catholic, English or Roman? That was one arena of the family fight but there were others. Peter Marsh points out that ritualist innovations had an empowering effect on working class parishioners, with the most accepting London neighborhoods for church innovations being the so-called slums, where “rich worship offered a solitary source of beauty among desolation” (114). Another battleground was in Punch. When a family fight gets going, how the others act and what they look like are the first targets. So we find plenty of cartoons that bring together “smart” readers from a swath of British life--old-line families, the new bourgeoisie and free-thinking liberals-- to have a laugh at the Ritualists. Articles and gossip put down the “trifling” churchmen with that age-old slur, a “want of manliness.” In Punch, their priest with a receding chin is snubbed by John Bull and his associates.

Punch cartoons mocking Ritualism: Left: Over the Way (17 November 1866). Right: Pernicious Nonsense (November 3, 1866). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

As a Ritualist priest walks by swinging a censer out of which pours incense smoke, John Bull, the symbol of England, tells the assembled clergymen: “I pay your reverences to look after my establishment, and if you neglect your duty, I shall see to it myself.” In another cartoon of 1866, “Dr. Protestant,” tall and stern (and possibly a portrait of John Knox), makes his own aesthetic pronouncement. He tells a group of small Ritualist priests with the same receding chins, “Take your gewgaws…. I won't have them,” another allusion to the controversy over the visual component of the church service. Unfortunately, there is a tradition for this type of thing. A Tate Gallery exhibition of 2013 showed the knotty problem having roots at least back to the iconoclasm of the 1640s when the Puritan government ordered functionaries to deface or destroy religious art it condemned as ‘monuments of superstition and idolatry.” Though the Victorian reaction to Ritualism was more civilized, it is part of an ongoing argument over what is right in moments of worship for the English to look at.

Today too, with Donald Trump becoming US president, sensibilities are changing. In the last few decades, there have never been so many American trying to find what they believe in and what they want the country to feel like and the discourse to sound like. Again, philosophy but also aesthetics. In New York City, Trump Tower is a new icon that some treasure, some accept as the new normal, and others want to smash. U.S. artists are organizing to defend aesthetic essentials: viewpoints, but also specific visuals that should be “allowed.” It was like this in Victorian England. Business was booming, steam pushed industry, and English world power was enormous. But the central question was “How should we be?”

The Art World

his struggle for control played out in the Victorian art world. Most importantly for our investigation, and having something in common with the “take your gewgaws elsewhere” cartoon is the question of when beauty is manly and good and when it is sentimental, feminine and supposedly less good. This is one of the problems the English sensibility struggled with from 1850 to 1900. Religion had diminished in power, so increasingly, the question of what was important to know, to love, to feel, and to see was asked in the arts. There is a connection here between worship and art, for the same impulse for dramatic ceremony and the involvement of the senses that helped drive the Ritualist movement also drove painters to choose new subject matter, new forms and new colors to express the new English sensibility.

We see this art throughout the section on the visual arts in the Victorian Web and it has by no means a straight line of development; the artists are searching, tacking like sailboats. Ruskin himself, a key moralist and art critic from 1840 to 1880, evolved through several mind-sets and artistic preferences that each pointed in their own way towards modernism. He loved J. M. W. Turner’s land- and seascapes that challenge the viewer to think twice about realism and see nature as dynamically charged and perpetually changing. Then, around the same time that Ruskin lost his religious belief, he grew close to the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, a close-knit group of artists who painted religious subjects untraditionally in the name of personal feeling and a universal spirit. As George P. Landow argues, paintings of the Pre-Raphaelites, whose subjects were often inspired by revered devotional art of the Middle Ages and Renaissance, differed from those eras in two ways. First, the painters looked beyond the Christian meaning of scenes to focus on what Landow explains as their typologies or the universal truths they represent that are connected to other eras and global belief systems. This is a more modern outlook: it is not Christianity alone that speaks from their canvasses but “the unseen truths of the spirit.” The second breakthrough is that the group focused on painting before the reign of two-point perspective. This look backward was also a step forward, for by invoking an earlier way of seeing, the paintings prophesy modern art. By breaking perspective, flattening the picture plane, and accentuating the two dimensions of the canvas, they demand that viewers look anew.

In three pieces by Pre-Raphaelite artists, the subjects are traditional but the treatment is modern. The allusions to earlier art are clear but the effect is different. The compositions are more jarring; line and form speak directly to us. William Holman Hunt’s The Flight of Madeleine and Porphyro (1848) could be a traditional scene, but one compositional choice immediately sets it apart, the well-lit white diagonal of a drunken man’s fleshy thigh.

William Holman Hunt. [Eve of Saint Agnes] The Flight of Madeleine and Porphyro during the Drunkenness attending the Revelry. Oil on canvas. 1848. 75 x 113 cm. Collection: Guildhall Gallery, London. Reproduced courtesy of the City of London Corporation. Click on image to enlarge it.

The palpable weight of this body part listing to the right produces a tension between it and the lovers that hovers around the shadow in the center. Along with the unsettling realism of the claustrophobic purple and yellow-green atmosphere, Hunt puts us not in the past but now.

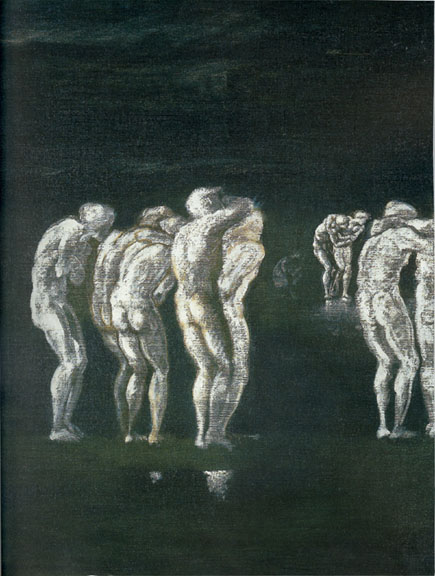

Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones. Souls on the Banks of the River Styx. c. 1873, Oil on canvas, 35 x 27 1/2 inches,. Courtesy of Peter Nahum Ltd.

In Edward Burne-Jones’s painting of souls on the River Styx of 1873, the chalk white souls move like modern dancers in a line. No grandeur, no common direction, no higher authority pulling or pushing, each alone, some shielding themselves, with no environment. Reed Keefe describes the painting in a way that signals its modernist tendency: “The shore that the figures look toward in the Ænied remains unseen. Only two entities comprise the painting — the souls and the murky space in which they find themselves lost” (Keefe).

In Burne-Jones’s “Study for the Sleeping Knights” (1870) it is as if knights from an earlier era have left their frame and stretched out on Jones’s canvas in a modern line of repeating circles. Their breastplates are as much in the air as on the ground and the knights’ very relaxation is contemporary. The curling branches cradle the composition as much as they cradle the knights. The flowers half floating and half grounded are a decorative addition signaling that along with his medieval allusions the artist claims a space for natural patterns and contemporary imagination. Viewers of the painting must have felt the thrill of entering a new space.

In 1870, Victoria had been queen for 33 years. Arnold had just brought out his idea that the aim of culture is Sweetness and Light in all areas of national life, but the younger generation was already snubbing his older-style Victorian seriousness and becoming attracted to simpler meanings of the words, sweetness standing for the senses and light for the pure excitement of discovery. For instance, the flowers that float about Burne-Jones’s knights turn up everywhere in Pre-Raphaelite art as signs of the transitoriness of life but also as surprising bursts of color. This resonates with the Ritualists whose impulse to rejuvenate the Church revolved around two poles, restoring old solemnities but also sharing joy with candles, flowers, patterned vestments and colored altar cloths. Another resonance is that the Church establishment reacted to the Ritualists with the charge of “sentimentalism…and a trifling want of manliness” and the art establishment charged the new art with unbridled hedonism. Many factors brought these criticisms down on the artists. Fear, loathing, and ambivalence intensified the anxiety of change. It can be argued that the late nineteenth century terms aesthetic, decadent art and art for art’s sake are somewhat demeaning ways of categorizing the attempt to break finally with traditions that seriously weighed artists down. For the late Pre-Raphaelites, the Symbolists, and other high-strung intellectuals of the fin-de-siecle, exhilaration was combined with often humiliating times.

Walter Pater Points to Modernism

During a change as big as this one, the progressive movement needed writers who could explain the transition to an establishment that was fearing it. From Oxford, Walter Pater filled this role. He sought “liberty of the heart” but also understood “the antagonism of the new” and acknowledged for his readers that the new world of thought and feeling might seem “desolate at first.” Pater’s teaching at Oxford and his encouragement of young writers was never forgotten by Oscar Wilde and W.B. Yeats, but by his university peers he was more often misunderstood, uncelebrated, and ridiculed. Pater had good credentials for being a charter member of what he termed “the irresistible modern culture,” for instance famously joking with a friend about taking religious orders just so they could wear the clothes and perform the rites. His Studies in the History of the Renaissance (text) got him (in trouble at Oxford in 1873 (“cold-blooded dilettantism”), but his success is now clear; he showed us how Renaissance artists took pleasure in the senses and the imagination which is what all high school students now learn in world history.

The success of the modern movement Pater promoted is also seen in our easy acceptance of the Renaissance “spirit of rebellion and revolt against the moral and religious ideas of the age.” It cannot have been easy in the 1880s to set the stage for modernism — Proust was 10 years old and Joyce and Woolf had not been born — and to promote Renaissance artists’ “intoxication with beauty as a rebellion, as something illegitimate and forbidden… as being comprehensible only in terms of contradiction to the norms of the age.” Gladly accepting the terms of the fight between artists and the establishment, Pater put his finger on the pulse of art when, in describing the triumphs of Da Vinci’s career, he said flat out, “the way to perfection is through a series of disgusts.” He pointed to the moment when Da Vinci was allowed to finish an angel in the left-hand corner of a painting by Verrocchio and stunned the master. The angel “may still be seen in Florence, a space of sunlight in the cold, laboured old picture.” What art does first is say goodbye to the previous way of seeing.

There might be no more modern term that relative and Pater used it as early as 1866, contrasting it with its foe, the absolute. In this excerpt, we have left the Victorian era:

Modern thought is distinguished from ancient by its cultivation of the "relative" spirit in place of the "absolute." …. Ancient philosophy sought to arrest every object in an eternal outline, to fix thought in a necessary formula… To the modern spirit nothing is, or can be rightly known, except relatively and under conditions…. The philosophical conception of the relative has been developed in modern times through the influence of the sciences of observation. Those sciences reveal types of life evanescing into each other by inexpressible refinements of change…. What the moralist asks is, Shall we gain or lose by surrendering human life to the relative spirit? Experience answers, that the dominant tendency of life is to turn ascertained truth into a dead letter — to make us all the phlegmatic servants of routine. The relative spirit, by dwelling constantly on the more fugitive conditions or circumstances of things, breaking through a thousand rough and brutal classifications, and giving elasticity to inflexible principles, begets an intellectual finesse, of which the ethical result is a delicate and tender justness in the criticism of human life [“Coleridge”]

There can be no doubt Walter Pater foresaw modern times. By finding sensual and aesthetic pleasure in the Renaissance he was breaking from dominant Victorian thinking. He put it this way: “In their care for beauty, in their worship of the body, people were impelled beyond the bounds of the primitive Christian ideal.” When Pater spoke of the liberated art world of the past, he was also describing the new art world that was forming in front of him and that he captured in modern phrases: “their love became a strange idolatry, a strange rival religion.” And true to a pattern we have seen, Pater brought back some old terms to describe the progressive changes he favored. In support of his artist friends, for instance, he reached for a category, antinomianism, historically used against religious Dissidents, a “state of grace that exempts the individual from following moral law” (Bennett). Pater called this noble and, in fact, cherished “this rebellious element, this sinister claim for liberty.”

Fiction and the Victorian Life-World

o conclude our look at this change in British sensibility, we follow Jacqueline Banerjee on the Victorian Web to Mrs. Humphry Ward’s best-selling novel, Robert Elsmere (1888). Fiction will help us experience the change, and we know we’re in the right place because Dr. Banerjee calls her article, “The Crisis of Faith.” Mrs. Ward takes the turbulent times, the ideas and the conflicts we have outlined and puts faces to them, faces showing emotion; when they are challenged philosophically, she brings us their gestures and how they walk away or stare or turn their heads. Ward (1851-1920) is just the writer for this. She was a rebellious young lady, an intellectual, a niece of Matthew Arnold, married to an Oxford tutor and someone who knew “those intellectual and religious movements that were like the meeting currents of rivers in a lake.”

We need go no further than Chapter 28 which Banerjee highlights. Robert Elsmere is the twenty-something rector of a parish in Surrey. He reminds us of Josef Altholz’s line that “All Victorians were earnest; it was important to be earnest; but clergymen were distinctively and preeminently earnest.” The sense of Altholz’s statement that men like Robert took everything hard, the good and the bad, the moral and the immoral, goes to the heart of why this era and these thinkers are important. They were the leading thinkers of England which in many ways was the leading country, first to industrialize fully, first to conquer and control so many, so we can see these Victorians as representative moderns. They may not have been right, or fair, or better, but they were leaders and their thought had consequences. Throughout the novel, Elsmere wrestles with conscience, the meaning of divinity, and where his loyalties lie. We also meet others in his life-world, chiefly his devout wife Catherine, his foil, who is intensely committed to the traditional Christianity, which, by this chapter, is exactly what Robert wants to leave. Will they be able to get through this together? He wants to but he also wants a more active faith which will take him into the homes and workplaces of the poor, and this is something Catherine has never imagined. Robert will believe in a Resurrection only if it revives the people. In the scene, Catherine turns her back on him because he seems to be asking her to give up the God she loves who is apart from history and above current events. As the plot moves on from here, we eventually see the full circle of their modern experience: Robert’s pleading in embarrassment and shame when trying to explain his plan … her plan to cut him off from ever again knowing her private devotional thoughts as she prays for him; but then her joining him, their working together with the poor, his death from over-work, and her continuing the work.

There is also an interesting visual moment that connects Elsmere’s thinking to the new art. In their first meeting, Robert notices Catherine’s purity with a trace of sadness, foreshadowing that in the end she will modify this purity to become more modern with him. He pauses to commemorate the moment, picturing Catherine as a medieval saint.

Her cheek was leaning lightly on her hand, her eyes had an unusual animation; and her long white dress, guiltless of any ornament save a small old-fashioned locket hanging from a thin old chain and a pair of hair bracelets with engraved gold clasps, gave her...nobleness and simplicity…. He could almost have fancied the dark red flowers in her white lap.

This could be a painting by a Pre-Raphaelite.

The Elsmeres embody the struggle and the change England experienced. Looking back with Robert on what it took for them to synthesize a new shared point of view, Catherine, like our thinkers and artists, admits that she has been “wandering in strange places, through strange thoughts.” She calls the experience a shock, a storm, and a “fiery furnace of pain.” But she says she has learned. “‘God has not one language, but many. I have dared to think He had but one, the one I know. I have dared'—and she faltered—'to condemn your faith as no faith …. But oh! take me back into your life! …. I will learn to hear the two voices.”

Works Cited

Allingham, Philip V. “Image, Allusion, Voice, Dialect, and Irony in Thomas Hardy's ‘The Oxen’ and the Poem's Original Publication Context.” The Victorian Web. Web. 5 February 2017.

Altholz, Joseph. “The Warfare of Conscience with Theology.” The Victorian Web. The Victorian Web. Web. 20 January 2017.

Arnold, Matthew. Culture and Anarchy. “Preface.” The Victorian Web. Web. 20 January 2017.

Barber, Tabitha. Art Under Attack. London: Tate, 2014.

Banerjee, Jacqueline. “The Crisis of Faith in Mrs. Humphry Ward's Robert Elsmere.” The Victorian Web. Web. 22 January 2016.

Bennett, Kelsey L. Principle and Propensity: Experience and Religion in the Nineteenth Century. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2014. "

Delaura, David. “Introduction.” Hebrew and Hellene in Victorian England: Newman, Arnold, and Pater. The Victorian Web. Web. 29 December 2016.

Hext, Kate. “ The Illusive, Inscrutable, Mistakable Walter Pater: an Introduction.” The Victorian Web. Web. 10 January 2016.

Johnson, E.D.H. “The Dialogue of the Mind with Itself.” The Victorian Web. Web. 23 December 2016.

Landow, George. “Arnold’s Religious Beliefs.” The Victorian Web. Web. 20 December 2016.

Landow, George. Victorian Types, Victorian Shadows: Biblical Typology in Victorian Literature, Art, and Thought. The Victorian Web. Web. 1 January 2017.

Marsh, Peter T. The Victorian Church in Decline: Archbishop Tait and the Church of England. New York: Routledge, 2016.

Pater, Walter. “Preface.” The Renaissance: Studies in Art and Poetry. The Victorian Web. Web. 20 December 2016.

Pater, Walter. “Coleridge.” Appreciations. London: Macmillan and Co., and New York, 1890): 64-106. Web version from Representative Poetry Online. 10 January 2017.

Schlossberg, Herbert. “ The Tractarian Movement.” The Victorian Web. Web. 5 January 2017.

Last modified 9 February 2017