ublishers in the UK these days tend to take the position that no art book can be commercially viable without some kind of public event to underpin and promote it; an exhibition, a symposium, a television programme - if an author hasn’t got one of these lined up, they can take their manuscript elsewhere, even if it concerns that marketing team’s darling, Pre-Raphaelitism (the other favourite being Impressionism, of course). At the same time, both publisher and author will want to see their book sell until it is sold out, so it must have a continuing life. These two books are symptomatic of this situation, the one being based on an exhibition at the Southampton City Art Gallery in 2019 and the other arising from a conference at York University the same year, but both aiming to make a long-term contribution to the study and enjoyment of Pre-Raphaelitism.

A new orthodoxy has taken over the treatment of Pre-Raphaelitism in the last decade whereby its original form and facts are assumed to be insufficient (cue that glib term of criticism, "not relevant") and it must be offered in revised form, re-characterised, involving different artists, telling reoriented stories or speaking to a more recent set of interests. These attempts to re-animate this important mid-nineteenth-century aesthetic give a limited amount of attention to the factual founders of the style, Millais, Holman Hunt, Rossetti and Ruskin, and expand their cast of characters and topics in diverse directions. Here, the publication Anderson has pulled together tracks the manifestations of Pre-Raphaelitism from its origins (1848) to the present day, while Youde and Wilkes’s collection attends exclusively to female actors in the Pre-Raphaelite circle.

In prosecuting these expansions of the topic, they share today’s common bias towards the second wave of Pre-Raphaelitism, the Rossettian version that Burne-Jones’s work came to typify for the public. This approach occludes landscape painting and scenes of modern life and emphasises works of the imagination, romance and lyricism. This is the popular culture or internet version of Pre-Raphaelitism, as Anne Anderson (p. 9) and Kirsty Stonell Walker (p. 69) make clear in Beyond the Brotherhood, wherein Simeon Solomon, Marie Spartali and J.W. Waterhouse are as likely to be named Pre-Raphaelites as Holman Hunt, John Brett and his sister Rosa. Neither of these volumes, then, will satisfy the more scholarly reader even while they both offer interesting, curious and stimulating subject-matter.

Beyond the Brotherhood covers (parts of) three centuries and makes use of the expertise of five writers – Anderson is the lead author, with art dealer Rupert Maas, contemporary painter Alan Lee, art historian Kirsty Stonell Walker and conservator Rebecca Moisan writing at lesser length. Their contributions vary considerably in volume, leading to a peculiarly unbalanced coverage of the declared topics (some late-stage revision of the brief, perhaps?). It is clear from both the eclecticism and the contrivances of the book that the territory covered by the original exhibition tried to accommodate as many works in the two sponsoring galleries’ collections as possible (the Russell-Cotes Art Gallery and Museum was the other partner), and among the more surprising works thus brought into play are on the one hand The Coronation of the Virgin by the obscure Allegretto di Nuzio (c 1350) and on the other Maxwell Armfield’s Central Park, New York (1916), hardly a predictable subject of late Pre-Raphaelitism. Nevertheless, it is refreshing to see such a figure as Armfield (1881-1972) coming into focus. Discussed alongside them, some gems, such as Charles Collins’s The Devout Childhood of St Elizabeth of Hungary (1852), Evelyn DeMorgan’s Aurora Triumphans (c 1886), Anna Alma-Tadema’s Drawing Room, 1a Holland Park (1887), Henry Justice Ford’s Remembering Happier Things (c 1921) and Alan Lee’s Merlin Dreams (c 1987); and some artists who are often left out or marginalised on such occasions, such as James Archer (1822-1904) and Noel Laura Nisbet (1877-1956).

Left: Evelyn DeMorgan’s Aurora Triumphans (c. 1886). Right: James Archer's Sir Launcelot Looks on Queen Guinevere (c. 1864).

Artworks are taken at face value rather than filtered through the intentions of their makers or the perceptions of critics and contemporaries, and readers may find themselves longing for some definitions or undergirding principles as they turn the well-illustrated pages. They might understandably be uncertain as to what the hallmarks of Pre-Raphaelitism ever were. For, in tracing the "Pre-Raphaelite legacy" of its title, the book’s authors – and principally Anderson, who is credited as the curator of the exhibition – seem reluctant to say whether this consists in the how or the what of painting (and to a lesser extent, design), or both. In this regard, the Edwardian period is especially poorly accounted for. Perhaps because of this conceptual uncertainty, the book finds no room for Stanley Spencer (1891-1959), in whose work an inter-war echo of the style is often seen, although it does mention in passing arcane figures such as the intriguing Isabel Saul and Elfreda Beaumont, and give (rather uncritical) space to The Ruralists, a 1970s group of whom Peter Blake was the best known. Perhaps the most novel aspect of Beyond the Brotherhood is its present-day finishing point of the crowd-pleasing art of the screen: fans of The Hobbit films and the A Game of Thrones series are enjoined to see the roots of their favourites in the work of Burne-Jones. While these examples of the legacy were presumably best seen in the gallery, the book’s illustrations serve them well.

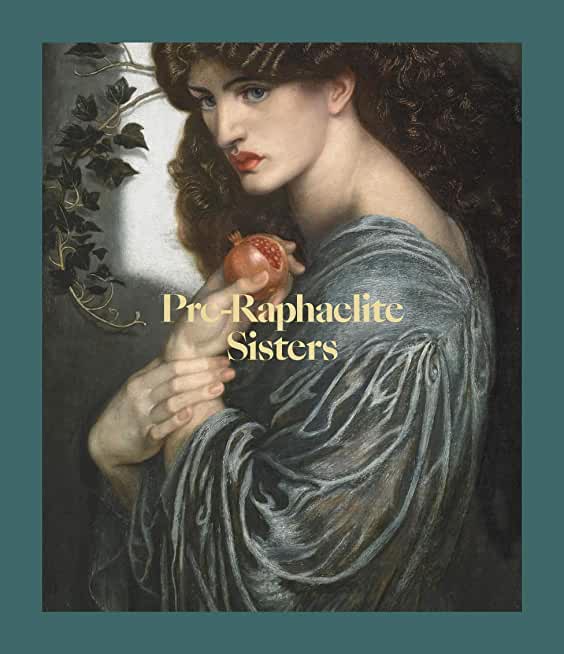

The book of essays crafted by Glenda Youde and Robert Wilkes from the papers given at a conference at the University of York is also anchored in an exhibition, Pre-Raphaelite Sisters (National Portrait Gallery, 2019, curated by Jan Marsh) whose title it borrows (and neither should be confused with Marsh’s earlier The Pre-Raphaelite Sisterhood). This presented a number of women connected with Pre-Raphaelitism either through their personal relationships, their cultural interests, or their work. This lengthy volume derives from the conference that complemented this show, and includes the work of no fewer than fifteen scholars, many of whom will be new to even the most assiduous readers on Pre-Raphaelitism. It follows the exhibition’s path, featuring a cast of artists, writers, models, muses and relatives. That being so, the reader can expect some fresh approaches and original thinking, along with new subjects.

Rather than chronology, the editors have preferred themes, with the essays grouped into four sections called "Making Art," "Poetry and Writing," "Female Agency," "Personal Perspectives." These overlap and bleed into each other, and essays on dress (Robyne Calvert) and "the Czech Rossetti" (Helena Cox) are especially ill served by the book’s structure.

As in Beyond the Brotherhood, the Rossettian version of Pre-Raphaelitism dominates. Thus the most frequently recurring figures are Eliabeth Siddal, Rossetti himself and his siblings Christina and William, Evelyn De Morgan and Burne-Jones. Welcome contributions from Margaretta Frederick and Charlotte Gere tread different territory, the former considering Barbara (Leigh Smith) Bodichon in the light of Deborah Cherry’s critical appraisal of her in 2000, and the latter drawing Georgiana (Georgie) Burne-Jones’ autobiography out of her loyal telling of her husband’s story. The final section is the most straightforwardly appealing, with Brian Eaton’s description of the gradual revelation of his ancestor Fanny Eaton’s biography and Hannah Squire’s account of an exhibition of Siddal’s drawings that she curated for the National Trust.

Ventnor, Isle of Wight, watercolour by Barbara Bodichon, née Leigh Smith (1827-1891), 1856.

Apart from new subject-matter, some originality of approach comes in the juxtaposing of figures who may have become familiar by now thanks to post-feminist scholarship, but whose depths have by no means been plumbed: thus Elizabeth Siddal’s and Georgiana Burne-Jones’ mooted collaboration on an illustrated book in 1860 (Nat Reeve), and relations between the eventual sisters-in-law Christina Rossetti and Siddal (Glenda Youde). These explorations may lack maturity of judgment and be less than thorough in their research – speculation on a historian’s part is only valuable where evidence is absent - but make for stimulating reading and indicate that much good work is being done in the history of art departments of certain UK universities.

Since a lot of ground is covered in this publication, it is unsurprising that there is much to disagree with. Sometimes the authors’ enthusiasm for their subject overbalances their consideration of the matter in hand: for instance, this reader was not convinced by Christin Neubauer’s argument for Eleanor Fortescue-Brickdale’s end-of-century work as expressions of the New Woman, nor by Caroline Giddis’ insistence on the feminism of Mary Watts’ work, nor Laura Nermel’s handling of landscape elements in Siddal’s work. Even within its own remit – the women of Pre-Raphaelitism – Pre-Raphaelite Sisters exhibits significant lacunae, and should perhaps have been entitled "Some Pre-Raphaelite Sisters": several women associated with the first iteration of the style, such as artists Rosa Brett, Anna Blunden and Jemima Blackburn and patron Ellen Heaton, deserve more recognition under this umbrella.

Pre-Raphaelitism is enjoying a surge of diverse attention these days, and as long as the major institutions holding the key works maintain its public visibility and the art market continues to promote its appeal we can expect its truths, its legends and its myths to continue attracting attention from multifarious quarters.

Bibliography

Anderson, Anne, et al. Beyond the Brotherhood: The Pre-Raphaelite Legacy. Bristol: Sansom and Co, 2019. 96pp ISBN 978-1-911408-55-0 £17.50

Bills, Mark ed. Art in the Age of Queen Victoria. London: Lund Humphries, 2001.

Burne-Jones, Georgiana. Memorials of Edward Burne-Jones. London: Macmillan and Co, 1904.

Cherry, Deborah. Beyond the Frame: feminism and visual culture. London: Routledge, 2000.

Marsh, Jan. The Pre-Raphaelite Sisterhood. London: Quartet Books, 1985.

Marsh, Jan et al. Pre-Raphaelite Sisters. National Portrait Gallery London, 2019.

A Victorian Salon: paintings from the Russell-Cotes Art Gallery and Museum. London: Lund Humphries, 1999.

Youde, Glenda, and Robert Wilkes eds. Pre-Raphaelite Sisters: Art, Poetry and Agency in Victorian Britain. Oxford: Peter Lang, 2022 (Cultural Interactions, vol. 49). 461pp ISBN 978-1-80079-564-8 $78.95

Created 20 February 2023