ecently there has been a proliferation of arts events across various disciplines celebrating the work of Black artists. Be it the Hayward Gallery’s recent show of the work of visionary Bahamian artist (and one time trainee cosmonaut!), Tavares Strachan; or the Serpentine South’s Spring celebration of the work of the legendary multi-discipline artist, Yinka Shonibare; or the celebrated Scottish Black poet, Jackie Kay, who was until 2021 Scotland’s poet laureate; and the V&A ‘s current yearlong celebration of the work of the legendary Black supermodel Naomi Campbell. Looking at these events, one could assume they are the direct result of a more accepting arts establishment, an establishment now much more willing to celebrate diversity. And although that is partially true, a closer inspection would also reveal that these events are simply a continuation of the long history of a Black presence in the world of the arts, a presence which crosses disciplines and which goes back several centuries. What’s even more astonishing is that many of these pioneering artists (and a celebrated artists’ model) were Black women. They, in many ways, are the often forgotten heroines of a little known past, a past very much worth celebrating. Below are the stories of just three of these extraordinary women.

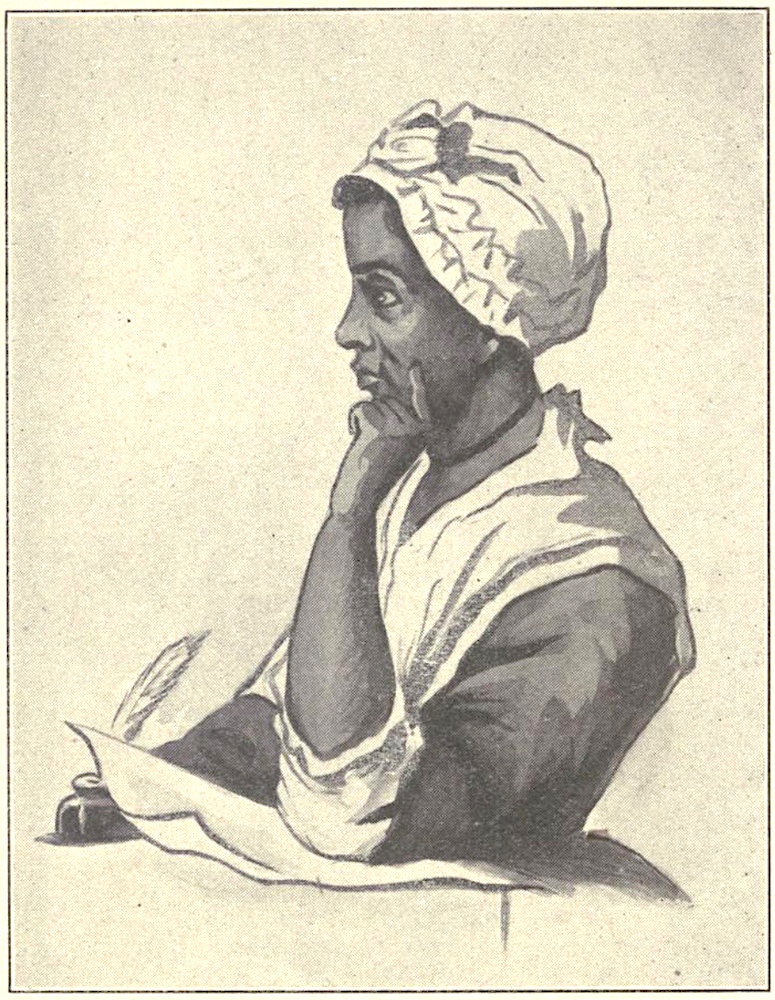

Phillis Wheatley, frontispiece to Poems.

One of the most celebrated poets of the eighteenth century was a young, enslaved Black woman. Her name was Phillis Wheatley (c. 1753-1784), and her personal story is as intriguing as the work she produced. Wheatley was taken from the coast of West Africa, possibly from modern day Senegal/Gambia, in about 1760. Historians estimate that she was probably between the ages of seven or eight when she was stolen from her home: an early poem is entitled, "An Address to the Atheist, by P. Wheatley at the age of 14 Years — 1767" (see Carretta 54). Named after the ship which brought her to America, The Phillis, the young child would be “bought” by a wealthy merchant, John Wheatley, who wanted a young servant for his wife. The family very soon discovered Wheatley’s prodigious ability for learning and they allowed their daughter, Mary, to be her first tutor. Phillis quickly mastered English and would go on to master both Greek and Latin. She immersed herself in the works of both Homer and Ovid and took inspiration from them in her own work. Phillis’ first poem was written at the age of thirteen and was entitled, "On Messrs. Hussey and Coffin." A eulogy, which she published later would bring her fame: "An Elegiac Poem, on the Death of that Celebrated Divine, and Eminent Servant of Jesus Christ, the Reverend and Learned George Whitefield." The piece was dedicated to the chaplain to the Countess of Huntingdon, a woman who would go on to become her patron.

Binding of the Poems.

By the age of eighteen, Wheatley had become a focus for the Abolitionist movement, which saw her intellect as an anti-slavery asset. The Wheatley family became aware of the international interest in this young woman and looked for a publisher in America for a collection of Phillis’s work but found none. So they sent her, accompanied by their son, to London, where they hoped publishers would be more sympathetic to the Abolitionist cause. With the help of the Countess of Huntingdon, whose interest in the book lent it "enormous prestige" (Robinson 190), they were successful and Wheatley’s collection, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral came out in 1773. Vincent Carretta describes her as having been "the the first person of African descent in the Americas to publish a book" and "the earliest international celebrity of African descent" (ix).

When Phillis found out that Mrs Wheatley was critically ill, she returned to the States, but some said she only did so once she had negotiated her freedom.

Wheatley is perhaps not as well-known as she should be because her poetry was inspired by a classical style which is now very much out of fashion. But her most famous poem, "On Being Brought From Africa to America," is a powerful indictment of those at the time who did not see enslaved Africans as equals, an idea that has a contemporary resonance. Critics today are also often frustrated by the fact that Wheatley’s poems are not a more direct condemnation of America, the very country which confined her through this hated institution for much of her young life, but it’s important to remember that she wrote for a specific audience, and this placed certain restrictions on her. So ultimately, she said what she was able to, given the times in which she lived.

She met key figures, including George Washington, who personally arranged a meeting after she wrote a poem dedicated to him. Probably her most personal writings were the letters she wrote to her close friend, Obour Tanner, a Black woman, ironically transported to America on the very same ship as Phillis. They remained close friends throughout Wheatley’s life, and after her death, Tanner kept the letters they had exchanged. Years later, the letters were donated to the Massachusetts Historical Society and their very existence has helped to secure Wheatley’s legacy.

Study of Fanny Eaton by Joanna Boyce Wells. [Click on this image for more information.]

Another pre-twentieth-century woman of note is Fanny Eaton (1835-1924), a favourite model for the young Pre-Raphaelite artists during the 1860s, many of whom wanted to make an Abolitionist statement in their work. Fanny Eaton was born Fanny Antwistle (or possibly Entwistle) in Jamaica in 1835 and travelled to London with her mother in the 1840s, a few years after the British Government had abolished slavery throughout the Empire. Fanny worked with her mother as a domestic servant in the homes of the affluent. She began her modelling career at a time coinciding with the rise of the Pre-Raphaelites. Artists who were inspired by Fanny included Simeon Solomon and his sister, Rebecca. Fanny sat for Simeon's Mother of Moses (Delaware Art Museum), a beautiful imagining of the biblical scene which was well-received when shown at the Royal Academy in 1860. Another stunning picture is Rebecca Solomon’s A Young Teacher (Tate Britain), in which Eaton appears as an Indian ayah, which also received favourable notice when exhibited the following year. Fanny then appeared as another biblical figure in The Mother of Sisera (Tullie House Museum and Art Gallery), 1861, by Albert Joseph Moore. That same year Fanny would sit for a personal favourite of the present writer, Head of Mrs Eaton (Yale Centre for British Art; shown on the right above) by Joanna Boyce Wells, a talented female artist whose early promise was sadly cut short by her death following childbirth soon after completion of the picture. Dante Gabriel Rossetti, perhaps the most celebrated of the Pre-Raphaelite artists at this period, executed a stunning charcoal portrait, simply entitled Study of a Young Woman (Mrs Eaton) in preparation for a larger work, The Beloved (Tate Britain) inspired by the "Song of Solomon" in the Bible. Fanny’s face, half hidden, peers out from amongst a bevy of maidens of diverse ethnic origin. For many of these artists, the availability of Fanny as a model offered an opportunity to paint subjects that were veiled references to slavery, an institution they despised.

Left to right: (a) Simeon Solomon's Mother of Moses (1860). (b) Rebecca Solomon's A Young Teacher (1861). (c) Dante Gabriel Rossetti's The Beloved (1863): Fanny Eaton's face can be seen in the background, on the right. [Click on these images for more information.]

One of Fanny Eaton’s latest known appearances is in a work by William Blake Richmond, entitled The Slave (Tate Britain), another strong Abolitionist statement since it appears to show a mother and child about to be sold. There was no firm dating for the picture, however, Jan Marsh thinks that it must have been painted in the 1860s during the period of Abolition (see Figes).

Edmonia Lewis, photographed by Henry Rocher (1826-1887), in about 1870, courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, on the Creative Commons licence (CCO).

The final figure in this remarkable trio of Black women is the sculptor Edmonia Lewis (c.1844-1907), one of the most acclaimed American artists of her generation. Lewis was born to a mother of African/ Native American descent and a father who was possibly author Robert Benjamin Lewis, also of African/ Native American descent. Edmonia’s parents died when she was still a child and her aunt and older half-brother helped to raise her. When that brother struck gold in the American West, he paid for Edmonia’s education. She attended Oberlin College, Ohio, a private liberal arts college, one of the few in the country which allowed African American and Native American students to attend. Edmonia’s time there would introduce her to the world of art but would also mark a disastrous turn in her life when she was accused of poisoning two fellow students, a scandal mentioned by Benedict Read in his seminal study, Victorian Sculpture (78). Although the charges were later dismissed, Lewis was nevertheless violently attacked by people from the town. Not long after, she was accused of stealing art materials from the school and, although there was no evidence, Edmonia was told she would not be allowed to register for her final term and so was not able to complete her degree. The College finally awarded her a degree in 2022. With the support of prominent figures, Edmonia received training with a well-respected sculptor, Edward Augustus Brackett, who specialised in marble portrait busts. Influenced by the Abolitionist movement, Edmonia executed busts of key figures of the period, including Robert Gould Shaw, the commander of the famous all black regiment, which was immortalised during the American Civil War. A film was made of this regiment in 1989, called Glory, starring Denzel Washington, for which he won his first Oscar.

Three works by Edmonia Lewis, left to right: (a) Bust of Christ (1870) in the forefront of an installation shot of the current Now You See Us exhibition at the Tate. (b) Moses (after Michelangelo) (1875). (c) The Death of Cleopatra (1876). [Click on these images for more information about them.]

With more commissions and the support of patrons, Lewis eventually had the funds to move to Rome where she settled and became one of a group of expatriate American women sculptors whose leader was Harriet Hosmer.

"Roma - Foro Romano. Veduta Generale, about 1880–1900," an albumen silver print, courtesy of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles Public domain).

Drawing heavily on the neo-classical tradition, Lewis’ fame grew and her work became known internationally. Perhaps the high point of her career was her participation in the Centennial Exposition, Philadelphia in 1876, for which she created what many now consider to be her masterpiece: The Death of Cleopatra (Smithsonian American Art Museum). The huge marble sculpture,, which is sometimes called "The Death Throes of Cleopatra," shocked many who saw it as it depicted the imagined agony of the Egyptian queen at the moment of her death. Weighing over 3,000 pounds, it is Lewis's largest work and some would say her most personal. No wonder Read feels that the "eminent American women sculptors" of this time (of whom he gives most space to Lewis) were "much more spectacular" than their British counterparts (78). Lewis was later commissioned to sculpt the head of former US president Ulysses S. Grant. However, the neoclassical style fell out of favour and work dried up. Lewis subsequently moved to London, where she died in Hammersmith in 1907.

These three women, the Poet, the Model and the Sculptor, made an enormous impact in the world of art and literature in their own time, but were then almost forgotten. When you next go to an exhibition of work by a famous Black artist, or look at the photos of a new Black supermodel or read the latest collection of poetry by a celebrated Black poet, remember these three women pioneers whose extraordinary lives and achievements opened doors for those who followed.

Bibliography

Carretta, Vincent. Phillis Wheatley: Biography of a Genius in Bondage. Athens, GA.: University of Georgia Press, 2011.

Figes, Lydia. "Fanny Eaton: Jamaican Pre-Raphaelite Muse." Art UK. Web. 13 August 2024.

Gerrish Nunn, Pamela. 'Artist and Model: Joanna Mary Boyce's Mulatto Woman', Journal of Pre-Raphaelite Studies 2, 1993

Marsh, Jan. "Pictured in Work — Employment in Art (1800-1900)." Belonging in Europe The African Diaspora and Work. Ed. Caroline Bressey and Hakim Adi. London: Routledge 2011. 50-59.

O'Neale, Sondra A. "Phillis Wheatley, 1753-1784." The Poetry Foundation. Web. 13 August 2024.

Powers, Hermania. "Who was Edmonia 'Wildfire' Lewis?" Art UK. Web. 13 August 2024.

Read, Benedict. Victorian Sculpture. New Haven & London: Yale Unversoty Press, for the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, 1982.

Robinson, William H. “Phillis Wheatley in London.” CLA Journal 21, no. 2 (1977): 187–201. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44329344.

Wheatley, Phillis. The Poems of Phillis Wheatley, as they were originally published in London. Republished. Philadelphia, Pa.: R.R. and C.C. Wright, 1909. Internet Archive, from a copy in the University of California Libraries. Web. 13 August 2024.

Created 13 August 2024