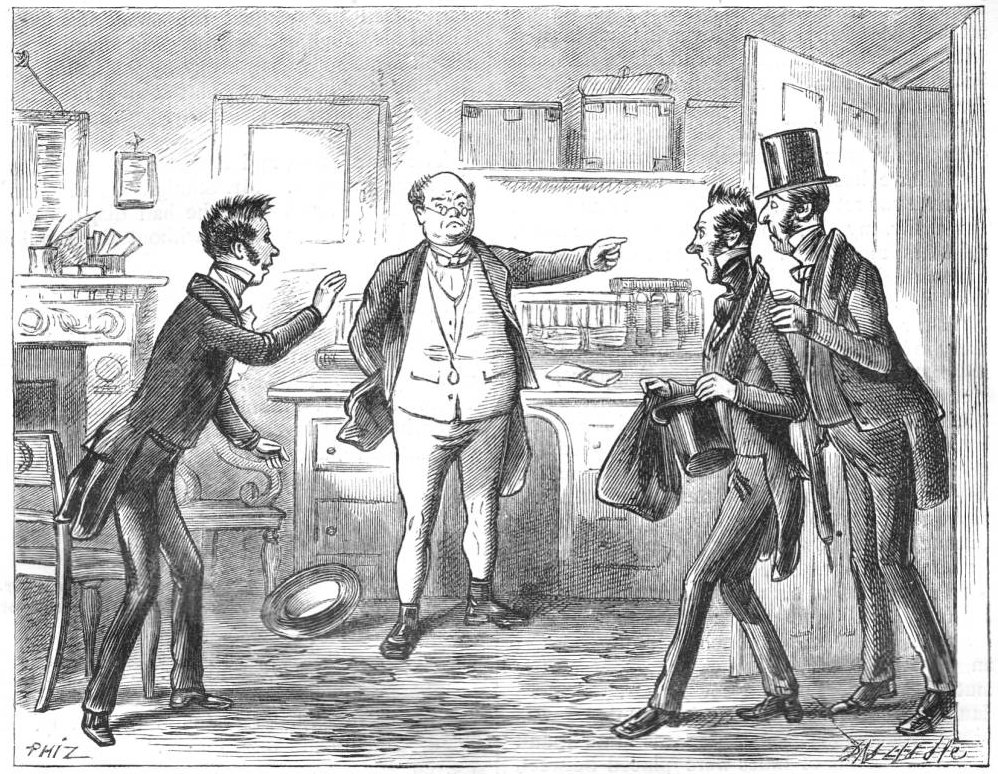

I say insolent familiarity, Sir," said Mr. Pickwick, turning upon Fogg with a fierceness of gesture which caused that person to retreat towards the door with great expedition (See page 374.) by Phiz (Hablot K. Browne). The British Household Edition (1874) of Dickens's Pickwick Papers, p. 384. Engraved by one of the Dalziels. Chapter LIII, “Comprising the final exit of Mr. Jingle and Job Trotter; with a great morning of Business in Gray's Inn Square. Concluding with a double knock at Mr. Perker's door,” 374. The composite woodblock illustration is 11 cm high by 14.2 cm wide (4 ¼ by 5 ½ inches), framed. [Click on image to enlarge it.]

Passage Illustrated: Pickwick's Final Exchange with the Scurrilous Attorneys

Then both the partners laughed together — pleasantly and cheerfully, as men who are going to receive money often do.

"We shall make Mr. Pickwick pay for peeping," said Fogg, with considerable native humour, as he unfolded his papers. "The amount of the taxed costs is one hundred and thirty-three, six, four, Mr. Perker."

There was a great comparing of papers, and turning over of leaves, by Fogg and Perker, after this statement of profit and loss. Meanwhile, Dodson said, in an affable manner, to Mr. Pickwick —

"I don't think you are looking quite so stout as when I had the pleasure of seeing you last, Mr. Pickwick."

"Possibly not, sir," replied Mr. Pickwick, who had been flashing forth looks of fierce indignation, without producing the smallest effect on either of the sharp practitioners; "I believe I am not, sir. I have been persecuted and annoyed by scoundrels of late, sir."

Perker coughed violently, and asked Mr. Pickwick whether he wouldn't like to look at the morning paper. To which inquiry Mr. Pickwick returned a most decided negative.

"True," said Dodson, "I dare say you have been annoyed in the Fleet; there are some odd gentry there. Whereabouts were your apartments, Mr. Pickwick?"

"My one room," replied that much-injured gentleman, "was on the Coffee-Room flight."

" Oh, indeed!" said Dodson. "I believe that is a very pleasant part of the establishment."

" Very," replied Mr. Pickwick drily.

There was a coolness about all this, which, to a gentleman of an excitable temperament, had, under the circumstances, rather an exasperating tendency. Mr. Pickwick restrained his wrath by gigantic efforts; but when Perker wrote a cheque for the whole amount, and Fogg deposited it in a small pocket-book, with a triumphant smile playing over his pimply features, which communicated itself likewise to the stern countenance of Dodson, he felt the blood in his cheeks tingling with indignation.

"Now, Mr. Dodson," said Fogg, putting up the pocket-book and drawing on his gloves, "I am at your service."

"Very good," said Dodson, rising; "I am quite ready."

"I am very happy," said Fogg, softened by the cheque, "to have had the pleasure of making Mr. Pickwick's acquaintance. I hope you don't think quite so ill of us, Mr. Pickwick, as when we first had the pleasure of seeing you."

"I hope not," said Dodson, with the high tone of calumniated virtue. "Mr. Pickwick now knows us better, I trust; whatever your opinion of gentlemen of our profession may be, I beg to assure you, sir, that I bear no ill-will or vindictive feeling towards you for the sentiments you thought proper to express in our office in Freeman's Court, Cornhill, on the occasion to which my partner has referred."

"Oh, no, no; nor I," said Fogg, in a most forgiving manner.

"Our conduct, sir," said Dodson, "will speak for itself, and justify itself, I hope, upon every occasion. We have been in the profession some years, Mr. Pickwick, and have been honoured with the confidence of many excellent clients. I wish you good-morning, sir."

"Good-morning, Mr. Pickwick," said Fogg. So saying, he put his umbrella under his arm, drew off his right glove, and extended the hand of reconciliation to that most indignant gentleman; who, thereupon, thrust his hands beneath his coat tails, and eyed the attorney with looks of scornful amazement.

"Lowten!" cried Perker, at this moment. "Open the door."

"Wait one instant," said Mr. Pickwick. "Perker, I will speak." [Chapter LIII, “Comprising the final exit of Mr. Jingle and Job Trotter; with a great morning of Business in Gray's Inn Square. Concluding with a double knock at Mr. Perker's door,” Chapman & Hall Household Edition, pp. 373-74]

Commentary: Pickwick vents his true feelings Mrs. Bardell's Attorneys

In closing the original serial illustrations, Phiz and Dickens provided a frontispiece that shows Sam Weller and Samuel Pickwick in the old gentleman's library, retired from their adventures and seated at a round table on which are books and an ink-stand, decanters and glasses, details suggesting that they (like the purchaser of the final instalment and of the volume edition) are enjoying the experience of reading about and reflecting on their adventures. Effective as this frontispiece may be in emphasizing the mutually supportive "Quixote/Panza" relationship of master and man, perhaps as co-editors of The Pickwick Papers, the elegantly-framed cameo does little to tie up the loose ends of the novel's chief plot, the machinations of the solicitors Dodson and Fogg in supporting Mrs. Bardell's breach of promise suit against the protagonist. Indeed, as a volume "frontispiece," it could not give away specifics about the outcome of the chief plot. The force of Nemesis or poetic justice (which a modern reader might term "closure") requires that the conclusion of the episodic novel involve the scurrilous lawyers' receiving some sort of comeuppance, however. And so, without Dickens dictating to him what the four plates for the final sequence of Household Edition chapters (originally, the "double" number of November 1837, comprising Chapters LIII through LVII) would be, Hablot Knight Browne was free at last to follow his inclination to see that in his final woodcuts the devious legal partners would be recipients of divine (if not human) justice in Perker's inner office at Gray's Inn, where shortly before Jingle and Trotter have been recipients of divine forgiveness.

Thus, in winding up the "Bardell versus Pickwick" plot visually, Phiz reintroduces the devious figures of Dodson and Fogg, last seen not in The Trial of Chapter XXXIV (for they are solicitors rather than barristers, and must utilise the professional services of a barrister such as the oratorical Serjeant Buzfuz), but in their interview with Pickwick and Sam at their chambers in "You just come avay," said Mr. Weller. "Battledore and Shuttlecock's a wery good game, vhen you an't the shuttlecock and two lawyers the battledores." The sharp-nosed attorney with the white waistcoat in that earlier illustration, standing behind the other, is probably Dodson, but neither attorney in this later illustration much resembles his earlier counterpart. Previously, in their own offices, operating in full view of their clerks, Dodson (right) and Fogg (centre), are large, even expansive figures full of "cheek" and self-confidence as they goad the inexperienced and naive Pickwick into slandering and even assaulting them as an extension of their "sharp practice" philosophy. As they observe of Pickwick when they meet him in Perker's office after his release from the Fleet, the retired merchant is not so large as before (they are referring to the effects of the prison diet, but they might also be commenting upon the effects of his recent suffering on his ego); however, now at a considerable disadvantage, with no witnesses biased in their favour to support their narrative of being vilified and even beaten, Dodson (right) and Fogg (immediately in front of him, centre) are physically diminished as they shrink from their indignant victim, his characteristic pose of having one hand under his coat tails as he gestures with the other (thereby recalling for viewers the opening scene of the novel, when he addressed the Pickwickians after dinner, in Mr. Pickwick Addresses the Club, April 1836).

The shading of their thin faces suggests not so much embarrassment as shock and even fear, as Phiz has them retreating into the open doorway. Phiz has chosen to give the umbrella to Dodson, mentioned in the text as belonging to Fogg, and replace it (and Fogg's gloves as theatrical properties) with a lawyer's blue bag, even though he has secured Pickwick's payment in a pocketbook. In other words, no longer directed by the author to remain scrupulously faithful to the details established by the text, apparently Phiz felt free to invent and adjust, his most significant change being the characterisation of the predatory attorneys, whose slapping of the pocket, coyly disclosing the charges, mock forgiveness and affability, and smirking certainly do not suggest that they are abashed by Pickwick's accusations any more than they were in their own office earlier. Perker's gesture implies that he desperately wants them to leave rather than precipitate an altercation, even as Pickwick sternly points them toward the door. Although Perker's clerk, Lowten, is not in evidence, the reader presumes that he is just outside the right margin of the illustration, on the other side of the open door. The passage realised in this dramatic illustration is this:

Unfortunately, Phiz could not capture the delightful comedy of Pickwick's denunciation of the black-suited rogues or communicate the irony of Pickwick's condemnatory interrogation of the lawyers or their shift in attitude from bantering superiority to fear for their safety. In the imaginative or "anti-reality" world of the nine interpolated tales of the novel, genuine Nemesis is possible, even logical, since these are oral tales with the traditional moral compass of cautionary and instructive short fiction. However, in the novel, the contemporary world of Charles Dickens (although the action is set back some half-a-dozen years from the time of part-publication and initial reading), a denunciation of meanness, baseness, and duplicity rather than a more severe punishment is the best that the middle-class reader, pondering the moral state of contemporary society, can expect — especially when looking for poetic justice that corrects the professional misconduct of lawyers.

Related Material

- The original November 1837 illustration of this scene by Phiz: Mr. Weller and his friends drinking to Mr. Pell

- The complete list of illustrations by Seymour and Phiz for the original edition

- An introduction to the Household Edition (1871-79)

Other artists who illustrated this work, 1836-1910

- Robert Seymour (1836)

- Thomas Onwhyn (1837)

- Felix Octavius Carr Darley (1861)

- Sol Eytinge, Jr. (1867)

- Thomas Nast (1873)

- Harry Furniss (1910)

- Clayton J. Clarke's Extra Illustrations for Player's Cigarettes (1910)

Scanned images and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the images, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State U. P., 1980.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File and Checkmark Books, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. Illustrated by Robert Seymour, Robert Buss, and Phiz. London: Chapman and Hall, November 1837. With 32 additional illustrations by Thomas Onwhyn (London: E. Grattan, April-November 1837).

_____. Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. 14 vols. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1867. Vol. 1.

_______. Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. Illustrated by Thomas Nast. The Household Edition. 16 vols. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1873. Vol. 4.

_______. Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ('Phiz'). The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1874. Vol. 6.

_______. Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 2.

Guiliano, Edward, and Philip Collins, eds. The Annotated Dickens.2 vols. New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1986. Vol. I.

Hammerton, J. A. The Dickens Picture-Book. London: Educational Book Co., 1910.

Johnannsen, Albert. "The Posthumous Papers of The Pickwick Club." Phiz Illustrations from the Novels of Charles Dickens. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; Toronto: The University of Toronto Press, 1956. Pp. 1-74.

Kitton, Frederic G. Dickens and His Illustrators. 1899. Rpt. Honolulu: U. Press of the Pacific, 2004.

Steig, Michael. Chapter 2. "The Beginnings of 'Phiz': Pickwick, Nickleby, and the Emergence from Caricature." Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington & London: Indiana U. P., 1978. Pp. 24-50.

Created 11 March 2012

Last modified 7 April 2024