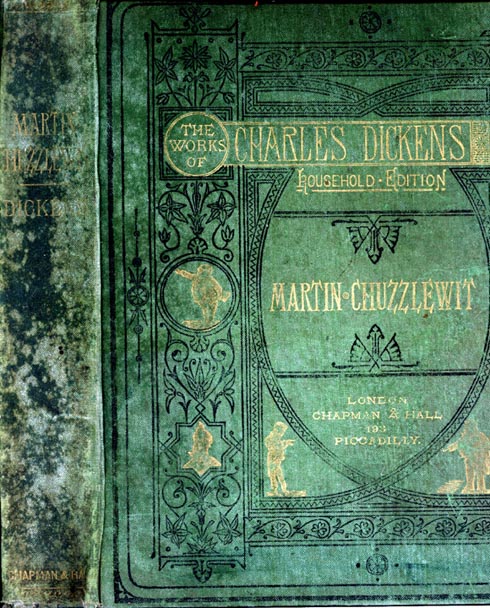

The green-and-gold embossed cloth cover of the Household Edition of the Works of Charles Dickens, Vol. 2, The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit, 1872.

The name of the new series, the first edition to be published after Dickens's death in 1870 — "The Household Edition — was chosen in part, of course, because of the appeal of Household Words, which readers brought up in the 1850s would probably have enjoyed as "family" reading. But "Household" may also refer to the fact that this was literally an edition "for the home," and was meant as a kind of "library edition" for ordinary readers and the less affluent, who would be able, through careful budgeting, to purchase the entire run of twenty-two volumes over a protracted period, either volume by volume or a single instalment per month. Perhaps, then, we should consider Chapman and Hall's entitling this large-format, beautifully bound edition as "being for the Victorian hearth and home," the gold-stamped binding recalling some of Dickens's best loved characters and the colour of the initial serial wrappers for the novels from 1836 through 1870.

The green-and-gold embossed cloth cover of the Household Edition of the Works of Charles Dickens, Vol. 11, Great Expectations, 1876.

Paul Davis in Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work indicates that Chapman and Hall issued the new series of Dickens's works, beginning about a year after his death and running all the way to the end of the decade, the last volume in the series fittingly being John Forster's The Life of Charles Dickens. Simultaneously, Harper and Brothers, one of Dickens's two North American licencees, issued its own set of Household Edition volumes, sometimes substituting the work of an American illustrator such as Thomas Nast or Charles Stanley Reinhart for the work of a British illustrator not so well known to the American book-buying public. The series on both sides of the Atlantic was amply illustrated in a manner that the original Chapman and Hall monthly parts could not have been, with large-scale woodcut illustrations dropped right into the letterpress, which was set in two columns with a border to emulate the appearance of Dickens's own weekly journal of 1850 through 1859, Household Words.

The question of why Chapman and Hall elected to publish the novels in the following order is a good one. The fact that several of what are now classified as 'late' or 'dark' novels were published quite early (especially Bleak House and Little Dorrit, but also Our Mutual Friend and A Tale of Two Cities) suggests that Dickens's British publishers assumed that these titles were still popular and would therefore be best-sellers in this new, highly attractive, well-illustrated format. The standard critical line about Dickens's early reception, starting with his biographer, John Forster, is that Dickens went into decline as a writer of novels (as opposed to his professional journalism) somewhere around Dombey and Son (1846) or even David Copperfield (1850). But this at least suggests that the later, longer novels maintained a popular appeal. Such a case cannot readily be made for Hard Times (1854), Great Expectations (1861), and The Mystery of Edwin Drood (1870). Some logistical factors that must have influenced the order of publication for Chapman and Hall, who elected to publish separate volumes for such short novels as A Tale of Two Cities rather than to combine them, as Harper and Brothers did, are as follows:

a. negotiations with Harper's about which volumes, based on American sales and the availability of American illustrators, should come first;

b. the continued strong sales of certain titles, such as The Pickwick Papers;

c. the number of volumes it could conceivably have the indefatigable Barnard illustrate;

d. the length of time it would take for the typesetting of the longer volumes;

e. the development of a schedule of publication that would reasonably space the publication of the twenty-two volumes over four years.

The Harper and Brothers Household Edition was 16 volumes (instead of 22, as in the case of the Chapman and Hall production), and came out between 1872 and 1877. Those volumes that were illustrated by American artists are as follows:

- The Old Curiosity Shop by Thomas Worth; (1872)

- Pickwick Papers by Thomas Nast (1873);

- Dombey and Son by William Ludlow Sheppard (1873);

- Nicholas Nickleby by Charles Stanley Reinhart (1875);

- Christmas Stories by Edwin Austin Abbey (1876);

- Hard Times by C. S. Reinhart (1876);

- Pictures from Italy and American Notes by Thomas Nast (1877).

Frederic G. Kitton adds that Reinhart illustrated the American printing of The Uncommercial Traveller, and that A. B. Frost (1876) did the illustrations for Sketches by Boz (1876).

As to the Household Edition's artists alluding to the work of earlier ones, especially Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz"): they certainly had the illustrations of the original artists in mind, but one cannot be certain as to whether the British illustrators of the Household Edition knew the work of slightly earlier/US illustrators, particularly Felix Octavius Carr Darley and Sol Eytinge, Junior. Barnard, as a great friend of Phiz, had access to the insights of the author, if only second-hand, when he worked on the hundreds of line drawings he was commissioned by the engravers, the Dalziel brothers, Edward and Thomas, on behalf of Chapman and Hall to produce for the new series.

Order of publication of individual works in the Household Edition (1871-78)

Dickens's works appeared in weekly numbers, monthly parts, and volumes in the following order:

- Oliver Twist, 1871 (Illustrator: James Mahoney)

- Martin Chuzzlewit, 1872 (Illustrator: Fred Barnard)

- David Copperfield, 1872 (Illustrator: Fred Barnard)

- Bleak House, 1873 (Illustrator: Fred Barnard)

- Little Dorrit, 1873 (Illustrator: James Mahoney)

- The Pickwick Papers, 1874 (Illustrator: Hablot Knight Browne)

- Barnaby Rudge; or, The Riots of 'Eighty, 1874 (Illustrator: Fred Barnard)

- A Tale of Two Cities, 1874 (Illustrator: Fred Barnard)

- Our Mutual Friend, 1875 (Illustrator: James Mahoney)

- Nicholas Nickleby, 1875 (Illustrator: Fred Barnard)

- Great Expectations, 1876 (Illustrator: Francis Arthur Fraser, 1846-1924)

- The Old Curiosity Shop, 1876 (Illustrator: Charles Green)

- Sketches by Boz, 1876 (Illustrator: Fred Barnard)

- Hard Times, 1877 (Illustrator: Harry French)

- Dombey and Son, 1877 (Illustrator: Fred Barnard)

- The Uncommercial Traveller, 1877 (Illustrator: Edward Gurden Dalziel)

- Christmas Books, 1878 (Illustrator: Fred Barnard)

- Child’s History of England, 1878 (Illustrator: John McLaren Ralston, 1849-83)

- American Notes and Pictures from Italy, 1878 (Illustrators: Arthur Burdett Frost and Gordon Thomson)

- The Mystery of Edwin Drood and Reprinted Pieces and Other Stories, 1879 (Illustrators: Luke Fildes, Edward Gurden Dalziel, and Fred Barnard)

- Christmas Stories 1879 (Illustrator: Edward Gurden Dalziel, 1849-1888)

- John Forster’s Life of Charles Dickens 1879 (Illustrator: Fred Barnard).

Bibliography

Cook, James. Bibliography of the Writings of Dickens. London: Frank Kerslake, 1879. As given in Publishers’ Circular The English Catalogue of Books.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Kitton, Frederic G. Dickens and His Illustrators. 1899. Rpt. Honolulu: U. Press of the Pacific, 2004.

Scenes and characters from the works of Charles Dickens; being eight hundred and sixty-six drawings, by Fred Barnard, Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz); J. Mahoney; Charles Green; A. B. Frost; Gordon Thomson; J. McL. Ralston; H. French; E. G. Dalziel; F. A. Fraser, and Sir Luke Fildes; printed from the original woodblocks engraved for "The Household Edition." London: Chapman and Hall, 1908.

Created 3 January 2013

Last modified 4 December 2024