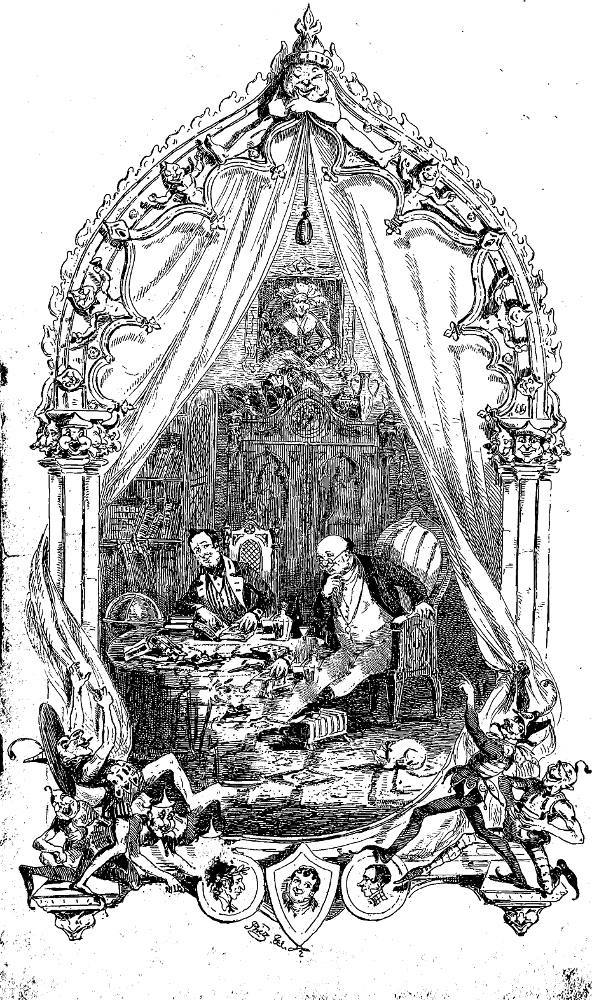

Pickwick and Sam Weller as Editors by Phiz (Hablot K. Browne) — final steel engraving for Charles Dickens's The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club; the two versions for the November 1837 (double monthly) number (Parts 19 and 20) and the 1838 bound volume, exhibit slight differences (see below), the most obvious being the partially shaded cat in Plate A (left) versus the white cat in Plate B (right). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Bibliographical Note: Frontispiece for Part Twenty (November 1837)

The original illustration, which is 18.5 cm high by 11.7 wide (7 ¼ inches high by 4 ½ inches, complements the engraved title-page, Tony Weller ejects Mr. Stiggins, also by Phiz for the final serial instalment (Parts 19 and 20) in November 1837. As Johannsen remarks, the chief differences between the two versions what he designartes as Plate 42, Frontispiece, (73) lie in the treatments of the cat, the striped footstool, and the signature. In Plate A:

e) The artist's signature, Phiz, fecit, is in the lower center, divided by a shield showing a sheep's-eyed Tupman portrait.

f) The cat is partly shaded. [73]

The situation for the signature in Plate B is different: the signature is now Phiz, del, and it at the left of the shield, "upon which Mr. Tupman's eyes are not so much upturned as before" (73). The cabinet behind the editors is much sharper in the second version.

Details

Context of the Illustration: "Retired" Pickwick as Editor

Mr. Pickwick himself continued to reside in his new house, employing his leisure hours in arranging the memoranda which he afterwards presented to the secretary of the once famous club, or in hearing Sam Weller read aloud, with such remarks as suggested themselves to his mind, which never failed to afford Mr. Pickwick great amusement. He was much troubled at first, by the numerous applications made to him by Mr. Snodgrass, Mr. Winkle, and Mr. Trundle, to act as godfather to their offspring; but he has become used to it now, and officiates as a matter of course. He never had occasion to regret his bounty to Mr. Jingle; for both that person and Job Trotter became, in time, worthy members of society, although they have always steadily objected to return to the scenes of their old haunts and temptations. Mr. Pickwick is somewhat infirm now; but he retains all his former juvenility of spirit, and may still be frequently seen, contemplating the pictures in the Dulwich Gallery, or enjoying a walk about the pleasant neighbourhood on a fine day. He is known by all the poor people about, who never fail to take their hats off, as he passes, with great respect. The children idolise him, and so indeed does the whole neighbourhood. Every year he repairs to a large family merry-making at Mr. Wardle’s; on this, as on all other occasions, he is invariably attended by the faithful Sam, between whom and his master there exists a steady and reciprocal attachment which nothing but death will terminate. [Chapter LVII, "In which the Pickwick Club is finally dissolved, and everything concluded to the satisfaction of everybody," final page]

Commentary: The Co-presenters of the Picaresque Novel

Dickens's initial illustrator, Robert Seymour, had chosen as the subject of his frontispiece Pickwick standing on a chair and addressing his dozen assembled disciples. Phiz, however, focussed on a relationship about which Seymour would have known nothing since he committed suicide in April 1836, just after he had completed the four plates for the May number — that between the faithful, street-wise Cockney valet Sam Weller and the naive retired businessman, Samuel Pickwick, a relationship which Dickens introduced in the tenth chapter. It is not difficult to interpret the present frontispiece as a testimonial to the iconic status of the two friends who become joint protagonists of the picaresque novel, and whom Phiz represents here as joint editors of the "posthumous papers" of the Pickwick Club, rather than of Pickwick himself.

Michael Steig notes the advance that Phiz's frontispiece represents over Seymour's, even though in construction it resembles Seymour's 1836 frontispiece for Thomas K. Hervey's The Book of Christmas:

If we take the title page to represent the novel's violently active comic side, the frontispiece is, with qualifications, the reverse: a scene of contemplative repose, observed and ridiculed, however, by a group of comic subversives. The basic structure of the frontispiece is like a proscenium stage, below which an imp points sardonically at three of the main actors in the novel who are absent from the stage, Tupman, Winkle, and Snodgrass. [38]

In the gothic niche composed of an ornate frame punctuated by gargoyles and surmounted by yet another a goblin, Sam Weller, easily recognisable by his striped vest, and Mr. Pickwick are reviewing books and papers in Mr. Pickwick's study. Clearly, then, in the frontispiece Phiz foreshadows the novel's closing paragraphs. He shows Sam Weller as one of the book's chief characters, even though he was not part of the story's original design, and arrived in the narrative in the sixth monthly number. Phiz implies by their central position and equal size that they are complimentary figures, like those in the niches in the oaken panel behind them. Significantly, Phiz has placed a large globe beside Sam's straight-backed chair, probably to imply his practical, real-world knowledge, in contrast to Mr. Pickwick's relaxed posture and his comfortable, overstuffed chair and hassock, which may represent a retired life of leisure and affluence, and therefore constitute something of a retreat from the world.

According to Steig, although Phiz here may well have been operating "under the stylistic influence of Seymour in The Pickwick Papers, his use of iconographic methods for the purpose of genuine interpretation and expression go beyond anything Seymour displayed as an illustrator" (pp. 39-40). In the autumn of 1837 as the serial was winding up, Phiz seems to have taken the opportunity of supplying a premonitory frontispiece for the novel's volume edition to comment upon the various genres one will encounter in The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. Instead of the incidental figures in Seymour's 1836 frontispiece, the harpist and Father Christmas, Phiz presents the laughing goblins to the left (in a broad-brimmed hat reminiscent of the goblin king's in Phiz's The Goblin and the Sexton) and to the right (dressed as a jester) as theatrical presenters who are drawing back the stage curtains on the novel as if its scenes constitute a play. Thus, Phiz may be implying through their presence that the narrative will reflect the early nineteenth century's three dominant dramatic forms: the farce, the melodrama, and the burletta. Phiz provides cameos the Pickwickian triad at the foot of the page (Tupman, Winkle, and Snodgrass) as waiting offstage and about to be introduced to readers of the volume. Steig offers further insights as why Phiz chose to allude to the Christmas number's supernatural illustration in the frontispiece's exuberant goblins, who point somewhat derisively towards Pickwick and Sam:

Robert Patten has demonstrated that this frontispiece, through its visual references to books and tale-telling, its pantomime imps (one of whom is the goblin of an earlier plate, The Goblin and [38/39] the Sexton . . . , its globe, helmet, and shield, epitomises the novel's use of the tale as a vehicle for conveying both experience and its evaluation (See Patten's "The Art of Pickwick's Interpolated Tales"). But in addition, the imps and goblins embody something of the tension in this novel between comedy as a moral vehicle and as a subversive force. Why, for example, is Gabriel Grub's goblin, whose function in the novel is to bring about the sexton's [moral and spiritual] regeneration, here mocking Pickwick and Sam? And why is another such figure jeering at the Pickwickians? [pp. 38-9]

Steig believes that the ornate gothic frame reveals the influence of Phiz's chief predecessor, Robert Seymour, specifically to the frontispiece entitled Christmas and His Children that Seymour had recently drawn for Thomas Hervey's The Book of Christmas (1836). In the centre, Seymour has placed a cluttered group of actors in Elizabethan costumes; to the right, Father Christmas gestures at the figures as if they are his family, while to the left a harper plies his instrument, as if to accompany the central characters in a Christmas carol. In both frontispieces, argues Michael Steig, "the central scene — intended to epitomize the book — is framed by a proscenium arch supported by Gothic columns. The stage is in each case revealed by a draped curtain, and both stages protrude into an apron. Below this stage is a satyr's head and below Browne's two, very similar to Seymour's" (39). Steig interprets the goblins not merely as symbols of Christmas traditions like the marginal figures in the Hervey illustration, but as more broadly indicative of Fancy or the creative imagination, which exerts considerable influence upon the novel's characters and situations. The goblins' imaginative influence is particularly evident in the novel's nine interpolated tales, notably Chapter 29's "Story of the Goblin Who Stole a Sexton." Steig believes that by giving these goblins such prominence in the design Phiz is implying "that reason and reflection in Sam and Pickwick are mocked by mirth and unreason — which are themselves ritualistic and seasonal rather than uncontained or destructive" (p. 39).

Related Material: Various Illustrated Editions

- The complete list of illustrations by Thomas Nast in the Harper & Bros. edition

- The complete list of illustrations by Phiz in the 1874 Chapman and Hall Household Edition

- An introduction to the Household Edition (1871-79)

- A selected list of illustrations by Harry Furniss for the Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910)

- Clayton J. Clarke's Extra Illustration for Player's Cigarettes (1910)

Other artists who illustrated this work, 1836-1910

- Robert Seymour (1836)

- Thomas Onwhyn (1837)

- Felix Octavius Carr Darley (1861)

- Sol Eytinge, Jr. (1867)

- Thomas Nast (1873)

- Harry Furniss (1910)

- Clayton J. Clarke's Extra Illustrations for Player's Cigarettes (1910)

Scanned images and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the images, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State U. P., 1980.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. Illustrated by Robert Seymour, Robert Buss, and Phiz. London: Chapman and Hall, November 1837. With 32 additional illustrations by Thomas Onwhyn (London: E. Grattan, April-November 1837).

Guiliano, Edward, and Philip Collins, eds. Dickens's The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. The Annotated Dickens. Vol. 1. New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1986. 2-533.

Hammerton, J. A. "Chapter Two: The Pickwick Papers." The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Library Edition, Vol. XVII. London: Educational Book Co., 1910. 84-128.

Johannsen, Albert. "The Posthumous Papers of The Pickwick Club." Phiz Illustrations from the Novels of Charles Dickens. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; Toronto: The University of Toronto Press, 1956. 1-74.

Steig, Michael. Chapter 2. "The Beginnings of 'Phiz': Pickwick, Nickleby, and the Emergence from Caricature." Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington & London: Indiana U. P., 1978. 24-50.

Vann, J. Don. "The Pickwick Papers, twenty parts in nineteen monthly instalments, April 1836-November 1837." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: The Modern Language Association, 1985. 61.

Created 22 November 2011 Last modified 26 March 2024