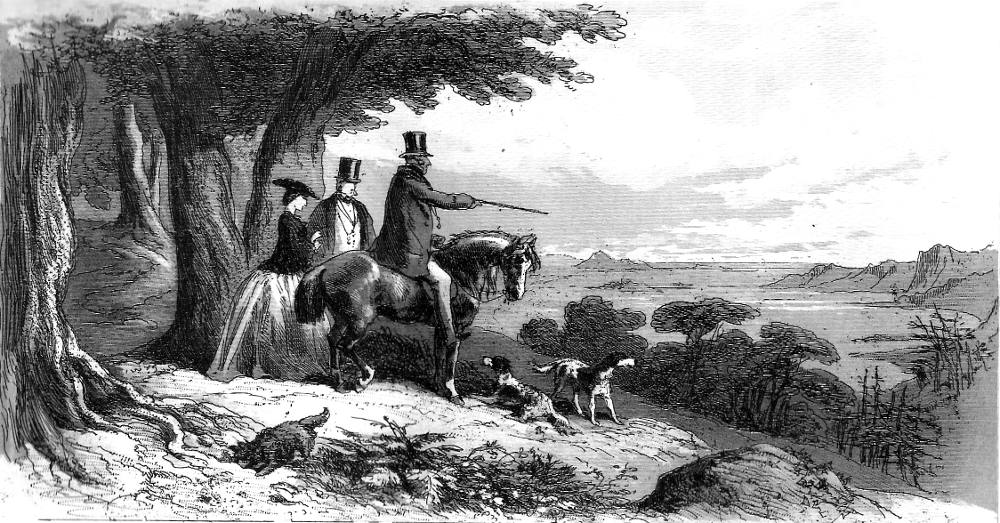

Lord Glengariff building a few Castles by Phiz (Hablot K. Browne), twenty-first serial illustration and eighth dark plate for Charles Lever's Davenport Dunn: A Man of Our Time, Part 10 (May 1858), Chapter 41, "A Country Walk," facing 331.

Bibliographical Note

This appeared as the twenty-first serial illustration for Charles Lever's Davenport Dunn: A Man of Our Time, steel-plate etching; 3 ⅝ by 7 inches (9.3 cm high by 17.6 cm wide), framed. The story was serialised by Chapman and Hall in monthly parts, from July 1857 through April 1859. The twenty-first and twenty-second illustrations in the volume initially appeared in reverse order at the very beginning of the eleventh monthly instalment, which went on sale on 1 May 1858. This number included Chapters XL through XLIV, and ran from 321 through 352.

Passage Illustrated: Castles in Spain versus Fisheries in Ireland

Meanwhile the old Lord floundered on, amidst crescents and bathing-lodges, yacht stations and fisheries, aiding his memory occasionally with little notes, which, as he contrived to mistake, only served to make the description less intelligible. At length he had got so far as to conjure up a busy, thriving, well-to-do watering-place, sought after by the fashionable world that once had loved Brighton or Dieppe. He had peopled the shore with loungers, and the hotels with visitors; equipages were seen flocking in, and a hissing steamer in the harbour was already sounding the note of departure for Liverpool or Holyhead, when Dunn, suddenly rousing himself from what might have been a revery, said, “And the money, my Lord, — the means to do all this?"

“The money — the means — we look to you, Dunn, to answer that question. Our scheme is a great shareholding company of five thousand — no, fifty — nay, I 'm wrong. What is it, Augusta?”

“The exact amount scarcely signifies much, my Lord. The excellence of the project once proved, money can always be had. What I desired to know was, if you already possessed the confidence of some great capitalist favourable to the undertaking, or is it simply its intrinsic merits which recommend it?”

“Its own merits, of course,” broke in Lord Glengariff, hastily. “Are they not sufficient?”

“I am not in a position to affirm or deny that opinion,” said Dunn, gravely. “Let me see,” added he, to himself, while he drew a pencil from his pocket, and on the back of a letter proceeded to scratch certain figures. He continued to calculate thus for some minutes, when at last he said: “If you like to try it, my Lord, with an advance of say twenty thousand pounds, there will be no great difficulty in raising the money. Once afloat, you will be in a position to enlist shareholders easily enough.” He spoke with all the cool indifference of one discussing the weather.

“I must say, Dunn,” cried Lord Glengariff, with warmth, “this is a very noble — a very generous offer. I conclude my personal security —”

“We can talk over all this at another time, my Lord,” broke in Dunn, smiling. “Lady Augusta will leave us if we go into questions of bonds and parchments. My first care will be to send you down Mr. Steadman, a very competent person, who will make the necessary surveys; his report, too, will be important in the share market.”

“So that the scheme enlists your co-operation, Dunn, — so that we have you with us,” cried the old Lord, rubbing his hands, “I have no fears as to success.”

“May we reckon upon so much?” whispered Lady Augusta, while a long, soft, meaning glance stole from her eyes.

Dunn bent his head in assent, while his face grew crimson.

“I say, Augusta,” whispered Lord Glengariff, “we have made a capital morning's work of it — eh?”

“I hope so, too,” said she. And her eyes sparkled with an expression of triumph.

“There is only one condition I would bespeak, my Lord. It is this: the money market at this precise moment is unsettled, over-speculation has already created a sort of panic, so that you will kindly give me a little time — very little will do — to arrange the advance. Three weeks ago we were actually glutted with money, and now there are signs of what is called tightness in discounts.”

“Consult your own convenience in every respect,” said the old Lord, courteously.

“Nothing would surprise me less than a financial crisis over here,” said Dunn, solemnly. “Our people have been rash in their investments latterly, and there is always a retribution upon inordinate gain!” [Chapter XLI, "A Country Walk," 331-32]

Commentary

The adjectives "noble" and "capital" subtly inform the reader as to the state of Lord Glengariff's mind as he builds a few "castles" or ideal buildings and pet projects in imagination. The question he raises, how to acquire the massive amounts of capital for such schemes, has already troubled Dunn in conference with Hankes. The loan with which he bought the Kellett estates for Lord Lackington he made with one of his own banks — in his own name. If Lackington defaults, Dunn could go bankrupt, dragging his financial empire with him. This was precisely the situation that led to the collapse of John Sadleir's finances and his ignominious suicide on Hampstead Heath, one of the chief contemporary events that prompted Lever to write the novel.

In the career and character of Davenport Dunn, Lever did not follow Sadleir in detail, but embodied various impression of the frenzied expansion of business which had struck him so forcibly during his London visit. [Stevenson, 223]

As Lever commenced work on the new serial novel for Chapman and Hall, the British press had been full of stories recently about catastrophic fall and suicide of the financial wizard and the subsequent financial scandal. The affair had come to light just as the Crimean War ended. The novelist may have also been assimilating into his fiction a personal crisis, for Lever's son, Charley, had resigned his commission at the end of hostilities, but had not returned to his father in London.

Just the year previous to this instalment, Phiz had been illustrating Dickens's Little Dorrit, another 1850s novel that makes capital use of the fall of the Irish financial wizard, so that the illustrator would have been aware of the connection between Dickens's Merdle and John Sadleir. However, as this instalment makes clear, Dunn is anything but an opportunistic swindler; indeed, both Lady Augusta Glengariff and Sybella Kellett are not far off the mark when they regard him as an Irish patriot bent on the restoration of the country's economy after half-a-century of political and social turmoil that included the rebellion of 1798, the potato famine, and the depopulation of the countryside.

From a compositional perspective, the reader has probably noticed that Phiz has given prominence to Lord Glengariff on his pony, pointing out to his guest, Davenport Dunn, the picturesque bay, the stone pines, and the "rocky promontory." What Phiz has deliberately avoided depicting is the "village" that Lever has the Lord mention: "The very spot we stand on is admirably suited to take a panoramic view of our little bay, the village, and the background" (330). Had he chosen an earlier moment in the chapter for realisation, Phiz might have included the young woman whom Augusta suspects is her rival for Dunn's affections, Sybella Kellett. The impression that Phiz is reinforcing is that Lord Glengariff has already accepted the possibility of Dunn's becoming his son-in-law, and that Sybella is not a serious competitor to Lady Augusta. The raw material that the aristocrat regards as having economic potential is picturesque and, at least in Phiz's illustration, unspoiled by human encroachment. The idyllic scene, however, requires development and aconstructed component if Glengariff is to make a profit and restore the family fortunes, but whether the development is oriented towards a fishery or tourism is immaterial from the nobleman's perspective, whereas Sybella would undoubtedly prefer commercial activity that would benefit the struggling peasants. That Lord Glengariff's tenants make no appearance in the realistic dark plate may suggest that Phiz is presenting not so much what is there, but what Glengariff feels is valuable because it could lead to profit. Dunn, according to the accompanying text, acquiesces in the local aristocrat's desire to raise capital in order to effect such improvements.

Phiz intersperses conventional engravings with more sombre dark plates to provide tonal differences, but the former are generally inferior to the latter in engaging the reader. Here, the unusually wide dark plate adds an unusual feature — an almost photographic and panoramic realism — in contrast to what the Irish nobleman imagines in the bay and the village. As Lord Glengariff floats his visions of a revitalised estate, Dunn is pondering Augusta's last private conversation with him in which she suggested that, if Dunn assisted her father in his development scheme, the crusty aristocrat would countenance Dunn's proposing for his daughter's hand.

Related Materials: Ireland's Troubles

Related Material: Financial Scandals

Working methods

- Dark Plate Etchings for Davenport Dunn

- Dark Plate Etchings for Bleak House

- Dark Plate Etchings for Mervyn Clitheroe

- "Phiz" — artist, wood-engraver, etcher, and printer

- Etching, Wood-engraving, or Lithography in Phiz's Illustrations for A Tale of Two Cities?

- Phiz: 'A Good Hand at a Horse' — A Gallery and Brief Overview of Phiz's Illustrations of Horses for Defoe, Dickens, Lever, and Ainsworth (1836-64)

Scanned image by Simon Cooke; colour correction, sizing, caption, and commentary by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.] Click on the image to enlarge it.

Bibliography

Brown, John Buchanan. Phiz! Illustrator of Dickens' World. New York: Charles Scribner's, 1978.

Lever, Charles. Davenport Dunn: A Man of Our Day. Illustrated by "Phiz" (Hablot Knight Browne). London: Chapman and Hall, 1859.

Lever, Charles. Davenport Dunn: The Man of The Day. Illustrated by "Phiz" (Hablot Knight Browne). London: Chapman and Hall, May 1858 (Part XI).

Stevenson, Lionel. Dr. Quicksilver: The Life of Charles Lever. New York: Russell & Russell, 1939, rpt. 1969.

Created 30 July 2019

Last modified 6 July 2020