Biographical Information

- Hablot Knight Browne, 1815-1882; A Brief Biography

- The Old Curiosity Shop Illustrated: A Team Effort by "The Clock Works"

Illustrations for Barnaby Rudge (13 Feb.—27 Nov. 1841)

Dickens made the expensive decision to have the illustrations dropped into the text, rather than printed on separate pages, so that they would retain the closest possible relationship to his story. This meant that the illustrators had to create their designs for wood instead of steel because wood engravings can be inked and printed simultaneously with the raised typeface, whereas etching plates, with their ink in grooves rather than on the surface, must be sent through a rolling press and printed on individual dampened pages. [Browne Lester, 77-78]

Comparing the plates that appeared in the 1849 edition of Barnaby Rudge to those in a good modern edition, such as the volume in the New Oxford Illustrated Dickens, gives us an idea of how the Victorian reader might have experienced the plates by Phiz — that is, simultaneously with the letterpress illustrated rather than facing such text. In the first place, whereas the illustrations in the New Oxford edition appear on a page 18.3 x 11.5 centimetres, those that Bradbury and Evans published in 1849 appear on a larger page (25 by 16.5 centimetres). The paper on which the original wood-cuts were printed provides a more important difference than their slightly larger page: in the 1849 edition, the plates appear on the same paper as does the text of the novel, and this arrangement permits printing text on the reverse of each illustration. In the New Oxford, the illustrations are free-standing rather than dropped into the text, usually facing the passages realised. In contrast, the original bound volume of 1849 has the plates on much heavier stock; in the 1849 edition the text bleeds through slightly, but in the New Oxford it does not, thus making the plates look somewhat better but also more important. Moreover, the ornamental capital letter vignettes designed by Phiz are not reproduced in modern editions, and pictures that served as head- and tailpieces merely appear on separate pages in the New Oxford. On the whole, the seventy-seven New Oxford Illustrated Dickens plates for Barnaby Rudge are quite clear, but those in the original often seem darker, sharper, and more dramatic.

Originally, when he proposed the novel to publisher Richard Bentley, Dickens had had veteran illustrator George Cruikshank in mind as his sole illustrator for the historical novel. However, when his editorial squabbles with Bentley came to a head, Dickens ceased work on the project, and Cruikshank took the commissions of a number of other authors, so that in January 1841 Dickens, taking up the novel again in earnest, suddenly found himself without Cruikshank. Thus, Dickens chose to revert to Phiz, his partner in The Pickwick Papers, who produced (according to Browne Lester) for the roaring tale fifty-nine illustrations, "mainly of characters, Cattermole producing about nineteen, usually of settings" (85). Browne Lester describes Phiz's specialty at this point as the "low" characters such as Hugh and Sim Tappertit, "active moments, and comic rascality, while Cattermole would embark upon loftier, antiquarian, angelic, and architectural subjects" (78).

Dickens concluded the miscellany with an illustration that looks very much like Cattermole's work, although in fact it is by Phiz. The tailpiece for Volume Three concerns the story about Master Humphrey's companion, the Deaf Gentleman, who appears in the final instalment of Master Humphrey's Clock (4 December 1841). The miscellany concludes in a melancholy fashion, with the Deaf Gentleman's finding Master Humphrey dead in his chair; the illustration The Deserted Chamber for "The Deaf Gentleman from his own Apartment" (Vol. III, 426), however, depicts neither the dead editor nor is friend, but only Master Humphrey's hat, cane, slippers, and volume of notes.

The Woodcuts Dropped into the Text

[The following table parallels the titles of the illustrations given by J. A. Hammerton in The Dickens Picture-Book (1910) for the original Phiz illustrations in the Bradbury & Evans single-volume edition of the novel (1849), which originally appeared in forty-two weekly parts in Master Humphrey's Clock, 13 February through 27 November 1841 (instalments 1 through 42). This same list of plates appears in The New Oxford Edition, pp. xvii-xix, but includes all of Cattermole's contributions in sequence.]

- The Maypole, by George Cattermole, frontispiece for the 13 February 1841 inaugural issue of Barnaby Rudge in Master Humphrey's Clock.

- Master Humphrey's Visionary Friends, illustration by Phiz for Master Humphrey's Clock (6 February 1841)

- Frontispiece to third volume of Master Humphrey's Clock (November 1841) which served as the frontispiece for Dec., 1849, single-volume.

- The Maypole, alternate design by George Cattermole, frontispiece 13 February 1841 in serial publication (first plate in the series). Part 1 in the novel, serialised in Master Humphrey's Clock, Vol. 3 (part 42), for the 13 February 1841 inaugural issue of Barnaby Rudge.

- 1. An Unsociable Stranger, Ch. I, 233

- 2. A Rough Parting, Ch. II, 242

- 2. Succouring the Wounded, Ch. III, 252

- 3. It's a Poor Heart that never Rejoices, Ch. IV, 259

- 4. Edward Chester Relates his Adventures, Ch. VI, 265

- 4. Barnaby's Dream, Ch. VII, 276

- 5. The Secret Society of the 'Prentice Knights, Ch. VIII, 280

- 5. Miggs in the Sanctity of her Chamber, Ch. IX, 286

- 6. Hugh, Ch. XI, 297

- 7. Barnaby and Grip, tailpiece for Ch. XII, Vol. II, 306

- 8. Mr. Haredale Interrupts the Lovers, Ch. XIV, Vol. III, 10

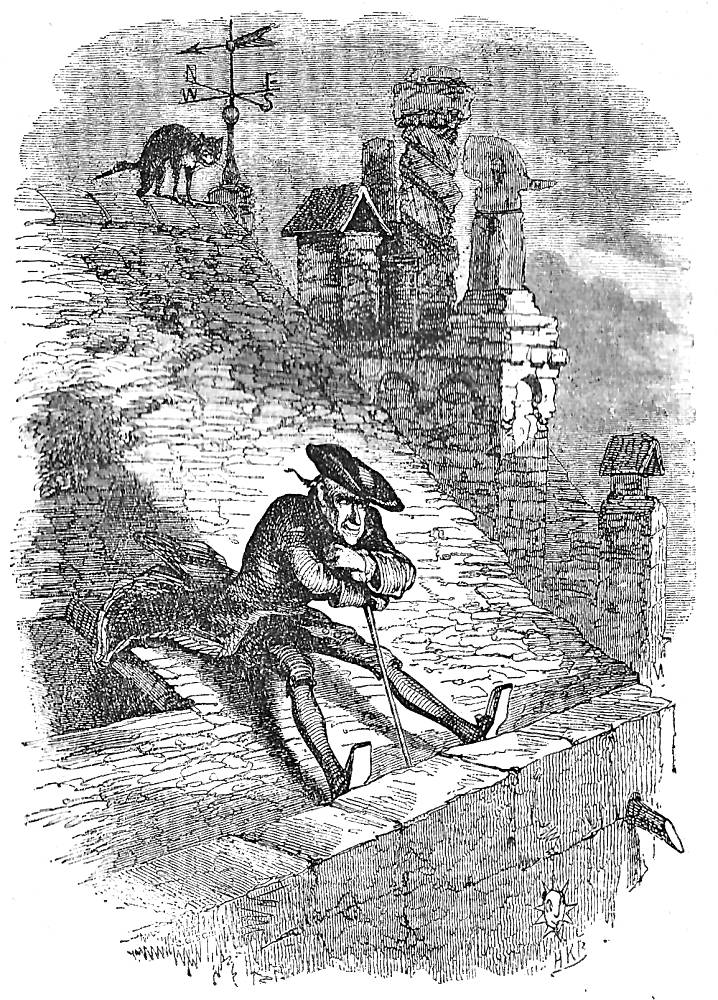

- 9. Mr. Chester takes his Ease at his Inn, Ch. XV, Vol. III, 14

- 10. Barnaby Greets his Mother, Ch. XVII, Vol. III, 28

- 10. Lighting the Noble Captain, Ch. XVIII, Vol. III, 35

- 11. Reading the Love-Letter, Ch. XX, Vol. III, 45

- 12. Hugh Accosts Dolly Varden, Ch. XXI, Vol. III, 49

- 13. Hugh Calls on his Patron, Ch. XXIII, Vol. III, 61

- 13. Purifying the Atmosphere, Ch. XXIII, Vol. III, 68

- 14. A Painful Interview, Ch. XXV, Vol. III, 77

- 15. Mr. Chester Making an Impression, Ch. XXVII, Vol. III, 89

- 16. Old John Restrains his Son, Ch. XXX, Vol. III, 107

- 17. Joe Bids Dolly Good-bye, Ch. XXXI, Vol. III, 109

- 17. Mr. Chester's Diplomacy, Ch. XXXII, Vol. III, 118

- 18. Solomon Frightened by a Ghost, Ch. XXXIII, Vol. III, 121

- 18. Old John's Bodyguard, Ch. XXXIV, Vol. III, 131

- 19. Distinguished Guests at the Maypole, Ch. XXXV, Vol. III, 137

- 20. Another Protestant, Ch. XXXVII, Vol. III, 152

- 20. A No-Popery Dance, Ch. XXXVIII, Vol. III, 156

- 21. Mr. Tappertit finds an Old Friend, Ch. XXXIX, Vol. III, 157

- 21. Mr. Tappertit's Harangue, Ch. XXXIX, Vol. III, 161

- 22. The Locksmith Dressing for Parade, Ch. XLI, Vol. III, 175

- 23. Mr. Haredale Defies the Mob, Ch. XLIII, Vol. III, 188

- 24. The Rudges' Peaceful Home, Ch. XLV, Vol. III, 195

- 24. Stagg's Demand, Ch. XLV, Vol. III, 199

- 25. Grip's Performance, Ch. XLVII, Vol. III, 208

- 25. Barnaby is Enrolled, Ch. XLVIII, Vol. III, 213

- 26. Lord George brings News of the Debate, Ch. XLIX, Vol. III, 217

- 27. The Rioters with their Spoils, Ch. LII, Vol. III, 240

- 28. The Secretary's Watch, Ch. LIII, Vol. III, 246

- 29. Old John at a Disadvantage, Ch. LV, Vol. III, 254

- 30. Barnaby Taken Prisoner, Ch. LVII, Vol. III, 265

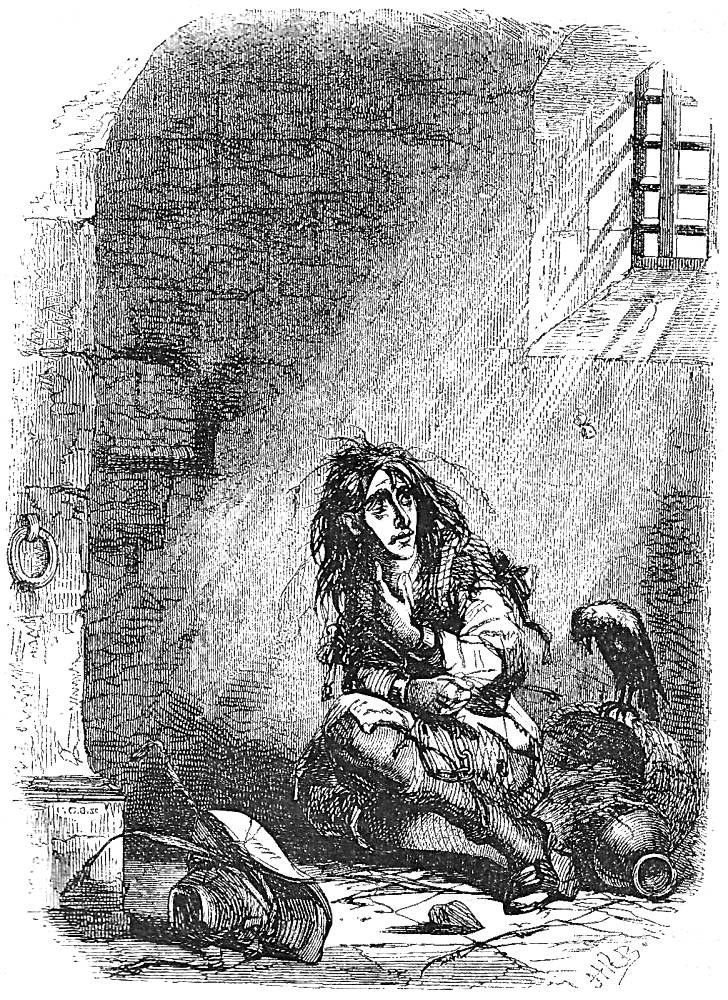

- 30. Barnaby in Newgate, Ch. LVIII, Vol. III, 276

- 31. Dolly in Hugh's Arms, Ch. LIX, Vol. III, 284

- 32. The Murderer's Confession, Ch. LXII, Vol. III, 294

- 32. Father and Son, Ch. LXII, Vol. III, 300

- 33. The Locksmith Undaunted, Ch. LXIV, Vol. III, 309

- 34. The Hangman's Badinage, Ch. LXV, Vol. III, 313

- 34. The Rioters at Work, Ch. LXVI, Vol. III, 324

- 35. To the Rescue, Ch. LXVII, Vol. III, 331

- 35. The Rabble's Orgy, Ch. LXVIII, Vol. III, 336

- 36. "You are Wenus, you know." Ch. LXX, Vol. III, 346

- 37. A Joyful Meeting, Ch. LXXI, Vol. III, 355

- 38. Intruding upon the Privacy of 'A Gentleman.' Ch. LXXIII, Vol. III, 367

- 38. In the Condemned Cell. Ch. LXXIV, Vol. III, 370

- 40. Hugh's Curse. Ch. LXXVII, Vol. III, 391

- 40. Dolly Embraces Joe, Ch. LXXVIII, Vol. III, 395

- 41. Mr. Haredale Bestows his Niece's Hand, Ch. LXXIX, Vol. III, 400

- 41. Miggs's Short-Lived Joy, Ch. LXXX, Vol. III, 406

- 42. The Deserted Chamber, from Master Humphrey's Clock, tailpiece to the volume, and "The Deaf Gentleman from His Own Apartment," Vol. III, 426.

Eleven Initial-letter Vignettes designed by Phiz (by instalment number)

- 1. Initial Letter "I," Ch. 1, p. 229: 13 February 1841

- 4. Initial Letter "B," Ch. 6, p. 265: 6 March 1841

- 8. Initial letter "I," Ch. 13, vol. 2, p. 1: 3 April 1841

- 13. Initial letter "T," Ch. 23, p. 61, vol. 2: 8 May 1841

- 17. Initial letter "P," Ch. 31, p. 109, vol. 2: 5 June 1841

- 18. Initial letter "O," Ch. 33, p. 121, vol. 2: 12 June 1841

- 21. Initial letter "T," Ch. 39, p. 157: 3 July 1841

- 26. Initial letter "T," Ch. 49, p. 217: 7 August 1841

- 30. Initial letter "B," Ch. 57, p. 265: 4 September 1841

- 34. Initial letter "D," Ch. 65, p. 313: 2 October 1841

- 39. Initial letter "A," Ch. 75, p. 373: 6 November 1841.

The 1849 Cheap Edition: A Less Expensive Alternative Intended to Sell More Copies

After the highly illustrated and expensive 1841 single volume with all the plates from Master Humphrey's Clock, Chapman and Hall then issued the novel in weekly parts from November 1848 though April 1849 (culminating in an actual volume. The Cheap Edition featured only five illustrations, only one of which was by Phiz, the new frontispiece; the remaining steel engravings were by portrait painters John Absolon and Fanny Corbeaux: Emma Haredale; Dolly Varden; and Barnaby Rudge (all engraved by Edward Finden, except for the frontispiece by W. T. Green). In these steel-engravings one may detect a marked shift from Cruikshankian humour and caricature towards realistic, albeit somewhat charming, portraiture. The publishers added two further illustrations for the novel's two-volume Library Edition (1858-59).

- Dolly Varden observed by Hugh, hiding in the bushes, from The Cheap Edition, frontispiece (1849)

- Title-page vignette: Miss Miggs

- Emma Haredale, from The Cheap Edition

- Dolly Varden, from The Cheap Edition

- Barnaby Rudge, from The Cheap Edition

With a dedication to John Forster, who developed the notion of offering something better than the Cheap Edition, Chapman and Hall published the Library Edition in twenty-two uniform volumes in 1858-9 at 7s 6d each. Titles initially included Pickwick Papers, Nicholas Nickleby, Martin Chuzzlewit, The Old Curiosity Shop, Reprinted Pieces, Barnaby Rudge, Hard Times, Sketches by Boz, Oliver Twist, Dombey and Son, David Copperfield, Pictures from Italy, Bleak House, Little Dorrit, and the Christmas Books. The publishers kept costs down by issuing only frontispieces as illustrations.

George Cattermole's 17 Contributions to the 1841 Serial (by instalment number)

- 1. The Maypole, Ch. I, Vol. II, 229 (13 February 1841)

- 3. Mr. Tappertit's Jealousy, Ch. IV, Vol. II, 260 (27 February 1841)

- 6. The Best Apartment at The Maypole, Ch. IX, Vol. II, 291 (20 March 1841)

- 8. The Warren, Ch. XIII, Vol. III, 1 (3 April 1841)

- 9. The Watch Crying the Hour, Ch. XVI, Vol. III, 21 (10 April 1841)

- 12. The Maypole's State Couch, Ch. IV, Vol. III, 60 (1 May 1841)

- 14. Old John Asleep in his Cozy Bar, Part Fourteen, Chapter 25 (15 May 1841).

- 16. Miss Haredale on the Bridge, Chapter 29 (29 May 1841).

- 22. Mr. Haredale's Lonely Watch, Chapter 42 (10 July 1841).

- 23. A Chance Meeting in Westminster Hall, Chapter 43 (17 July 1841).

- 27. The Rioters' Headquarters, Ch. LII, Vol. III, 238 (14 August 1841)

- 28. A Raid on the Bar, Ch. LIV, Vol. III, 250 (21 August 1841)

- 29. The Murderer Arrested, Ch. LVI, Vol. III, 264 (28 August 1841)

- 31. The Ladies' Escort, Ch. LIX, Vol. III, 279 (11 September 1841)

- 36. Carrying Off the Prisoners, Ch. LXIX, Vol. III, 343 (16 October 1841)

- 42. Sir John Chester's End, Ch. LXXXI, Vol. III, 415 (27 November 1841).

Related Resources Including Other Illustrated Editions

Right: Felix Octavius Carr Darley's study of Barnaby Rudge and Grip the Raven from Character Sketches from Dickens (1888).

- Dickens's Barnaby Rudge (homepage)

- Cattermole's Seventeen Illustrations for Barnaby Rudge (13 Feb.-27 Nov. 1841)

- Felix Octavius Carr Darley's Six Illustrations for Barnaby Rudge (1865 and 1888)

- Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s Diamond Edition Illustrations for Barnaby Rudge (1867)

- Fred Barnard's 46 Illustrations for the Household Edition of Dickens's Barnaby Rudge (1874)

- A. H. Buckland's six illustrations for the Collins' Clear-type Pocket Edition of Dickens's Barnaby Rudge (1900)

- The Charles Dickens Library Edition Illustrations for Barnaby Rudge by Harry Furniss (1910)

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Cohen, Jane Rabb. "Part Two: Dickens and His Principal Illustrator. 4. Hablot Browne." (Part 1). Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio U. P., 1980. 59-80.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1999.

Dickens, Charles. Barnaby Rudge, A Tale of the Riots of 'Eighty. Illustrated by J. Absalon and Hablot K. Browne ('Phiz'), and engraved by Finden. The Cheap Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1849.

Dickens, Charles. Barnaby Rudge. Illustrated by Hablot K. Browne ('Phiz') and George Cattermole. London: Bradbury & Evans, 1849.

Dickens, Charles. Barnaby Rudge. Ed. Kathleen Tillotson. Illustrated by Hablot K. Browne ('Phiz') and George Cattermole. The New Oxford Illustrated Dickens. London: Oxford University Press. 1954, rpt. 1987.

Hammerton, J. A. The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Library Edition, Illustrated by Harry Furniss. London: Educational Book Co., 1910.

Lester, Valerie Browne. Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004.

Steig, Michael. Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington & London: Indiana U. P., 1978.

Vann, J. Don. "Barnaby Rudge in Master Humphrey's Clock, 13 February-27 November 1841." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: Modern Language Association, 1985. Pp. 65-66.

Created 2 August 2015

Last modified 21 February 2025